Introduction

There has been a longstanding misperception within Defence, government and the general public that the ADF health services only need to provide treatment services. This notion fails to recognise the other two intrinsically linked ‘purposes’ (what would now be called ‘missions’) identified by Arthur Graham Butler in his seminal WWI medical history:1,2 enabling operational capability and facilitating civilian re-integration.

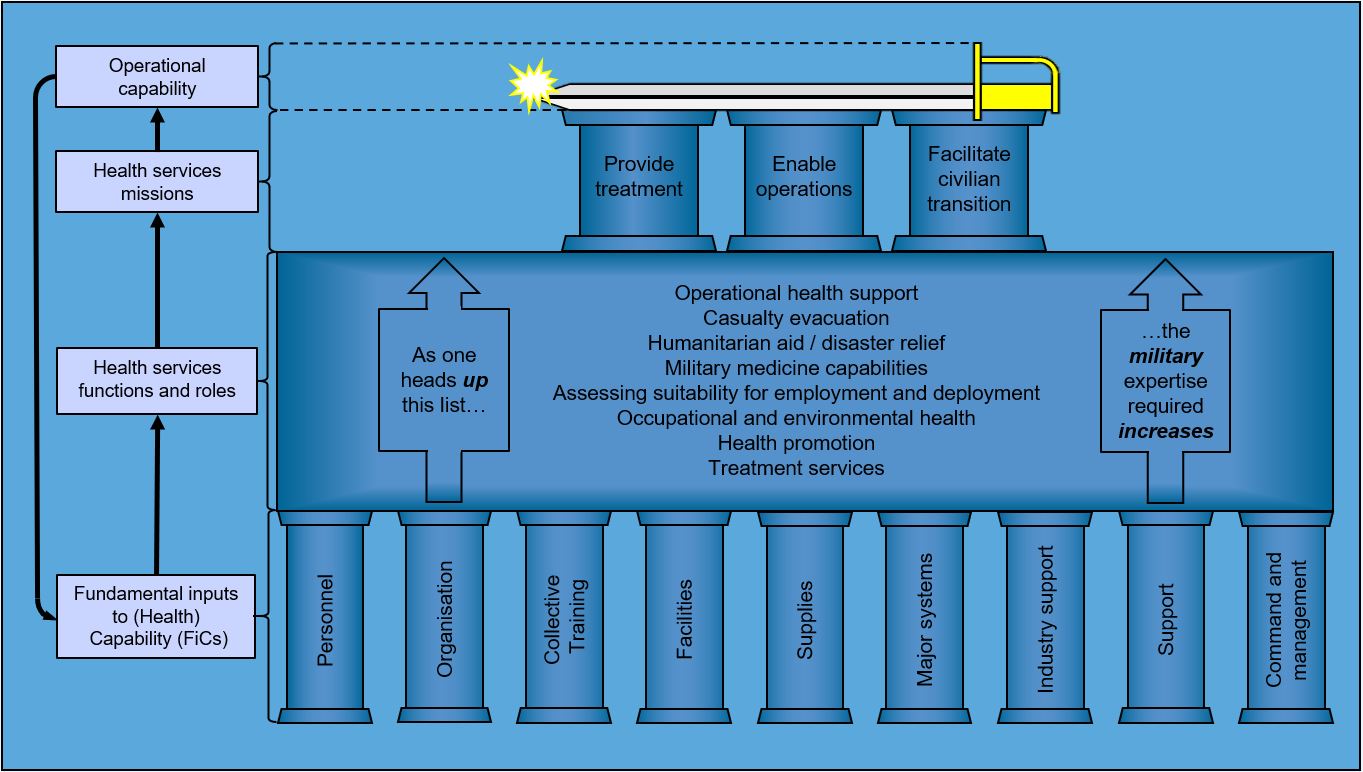

The paper originally intended to be first in this new series was intended to provide an overview regarding the Fundamental Inputs to (in this case, ADF health) Capability or FICs per the Defence Capability Manual (DCM), which the ADF’s health services need to perform the functions and roles required to fulfil their missions (Figure 1). Instead, the previous paper focused on the ADF’s health ‘organisation’ FIC,3 while this paper analyses the ‘personnel’ FIC.

Figure 1: The relationships between ADF operational capability, and the ADF health services’ missions, functions and roles and FICs.

Although this paper focuses on why and how Medical Officer (MO) recruiting and post-entry medical (as opposed to military) induction education and training requires elemental reform, many of the same issues pertain to ensuring that all ADF health personnel possess all the skills they need to play their part in fulfilling Butler’s missions via the aforementioned functions and roles.

Background

Before proceeding any further, it is first necessary to summarise how Figure 1 was derived.

(Health) FICs

The DCM defines ‘capability’ as the ‘power to achieve a desired operational effect in a nominated environment within a specified time, and to sustain that effect for a designated period’. It then explains how the following FICs generate ADF capability:4

- Organisation5

- Personnel (the subject of this article)

- Collective training

- Facilities

- Supplies

- Major systems

- Support

- Industry

- Command and management

This series of papers is premised on applying the DCM definition of ‘capability’ to the ADF health services: the ‘desired [health] operational effect in a nominated [health] environment’ pertains to fulfilling Butler’s missions via the functions and roles over an indefinite period.

Functions and roles

The author’s previous series of papers6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 explained the need for better workplace-related illness and injury prevention, not just to reduce the demand on Defence and the Department of Veteran’s Affairs (DVA) on their treatment and civilian re-integration services but also their generally avoidable impact on ADF operational capability. To that end, that series developed the following list of military health service functions and roles:

- Military health support

- Casualty evacuation

- Humanitarian aid/disaster relief

- Military medicine capabilities in support of the ADF’s aviation, diving and submarine operations, as well as chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defence

- Assessing health-related suitability for military employment and deployment

- Occupational and environmental health

- Health promotion

- Treatment services

These functions and roles are arranged in priority order: as one heads up the list, the level of military expertise required to conduct each one increases.

One of the articles in that series17 also formed the basis of submissions by the Royal Australasian College of Physicians to the 2019 Productivity Commission inquiry into veteran’s health, and the current Royal Commission on Defence and Veteran Suicide.18,19 It explained how reducing ADF workplace injuries would best be achieved by premising its health services on a systems-based occupational health strategic model.

Butler’s missions

Another article in that series20 explained how and why, despite having since been forgotten or ignored, Butler’s history represented 20 years of historical analysis that identified what would now be referred to as the three elemental and enduring missions of military health services. The same article also expanded on the contention that the ADF’s health services should be premised on an occupational-health-based systems model, and explained why healthcare for military workforces should be provided by practitioners under military discipline.

Although Butler understandably described them from a post-WWI Army perspective, that article also asserted that, although their implementation may differ, his missions remain relevant today to all three services in both peace and war. Unfortunately, only his ‘treatment service’ mission is resourced accordingly at present, including how ADF MOs are educated, trained and recruited.

Population factors driving the ADF health personnel FIC

Another article in the previous series21 explained why the size and scope of any health service should first reflect the demographics of the target population(s) they support. For the ADF population, these include (but are not limited to) being highly medically selected, (still) predominantly male, younger working age, widely geographically distributed and with high geographic mobility and turnover rates compared to the civilian community. Hence, rather than reflecting a typical civilian General Practitioner (GP) dependency, the ADF is, first and foremost, a workforce population.

Consideration also needs to be given to the generally preventable biological, physical, chemical, ergonomic and psychosocial workplace hazards to which the ADF population is exposed. Although many of these are not unique to the ADF, its personnel are arguably exposed to the most diverse range compared to other Australian workforces, even in the base setting. Meanwhile, ADF members in the deployed setting are exposed to even greater operational and non-operational hazards, the former including those that are deliberately intended to cause harm.

These considerations have two implications regarding the ADF’s health personnel FIC:

- The demand for clinical services such as paediatrics and geriatrics is eliminated, apart from niche HADR operations where the security situation precludes using non-military health agencies. Furthermore, the demand for other health services, such for age-related chronic conditions, is substantially reduced.22,23

- Conversely, the demand for other health services is substantially increased, such as those related to workplace- and sports-related musculoskeletal injuries, domestic- and workplace-related mental health issues, and risk-taking behaviours such as driving habits, horseplay, sexually transmitted disease and alcohol and other drug use. In addition, the scope of the women’s and men’s health services required are likewise affected by these factors.24

Hence, these factors drive the imperative to consider the ADF population as requiring bespoke military clinical skills and expertise to fulfil their ‘treatment service’ mission, in some respects not unlike the Australian indigenous and LGBTIQ+ subpopulations. However, fulfilling the ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions also drives an imperative to prevent and treat avoidable work-related injury and illness in the first instance.

MO induction education and training

The need for bespoke clinical military induction training is well-accepted by the ADF and its health services, as demonstrated by the Emergency Management of Severe Trauma course for all permanent ADF MOs as part of their initial career progression, and the single-service underwater and aviation medicine courses undertaken in Australia and overseas. Military clinical courses are also provided for procedural specialist MOs, such as the Definitive Surgical Trauma Care course and the Definitive Anaesthetic Trauma Course. Non-MO examples include the Dental Officer Initial Course (a module on battlefield facial injuries) and the Definitive Perioperative Nurses Trauma Course. To these can be added the basic and other courses provided for medical sailors, soldiers and airmen by the ADF School of Health and the single-service schools.

However, it should be noted that like the rest of medicine in general, these courses only provide skills-related training as to how to do certain things, rather than non-clinical education as to why they need doing in the first instance. Furthermore, there is currently no induction training or education for ADF medical or other clinicians to fulfil the ‘operational capability’ or ‘civilian re-integration’ missions. This paper asserts that such education and training should be based on fulfilling all three of Butler’s missions via the functions and roles per Figure 1 as follows:

- ‘Military health support’.25 This need only comprise awareness education as to why such support is necessary, prior to undertaking training as to how via the Joint Health Planning Course (typically at the O4 level some years later).

- Casualty evacuation.26 This also only needs to comprise awareness education as to why, before undertaking training as to how via the current fixed- and rotary-wing aeromedical evacuation courses.

- HADR.27 This would entail education as to why the scope of the ADF’s health services regarding HADR should be limited to supporting ADF and other entitled personnel, rather than providing direct treatment services for affected populations.

- Military medicine capabilities.28 This likewise only needs to entail education as to why the need exists for military-specific aviation, underwater and Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) training. As an aside, it should be noted that the last in-depth CBRN course was conducted in 2012.

- Assessing suitability for employment and deployment.29 This would entail education and training regarding:

- conducting occupational military medical, dental and psychological suitability assessments as intrinsic to every patient they see, and

- applying the ADF Medical Employment Classification (MEC) System as a personnel rather than a patient management tool.

- Occupational and environmental health.30,31,32 This refers to education regarding their contribution to putting the ‘health’ in ‘occupational health and safety’ (in particular, understanding why, when and how to seek advice), prior to undergoing further training (see below).

- Health promotion.33 This refers to education and training regarding workplace health promotion activities beyond the healthy lifestyle topics per the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) ‘Red Book’,34 especially in—but not limited to—the operational setting.

- Treatment services.35 Although the aim of this topic is not to teach their jobs, MOs still need education as to why their military clinical practice must extend beyond history-taking, physical examination, ordering investigations, formulating diagnoses and prescribing treatment, to also include:

– assessing and documenting the work-relatedness of their patient’s medical conditions for compensation and post-separation management purposes, and

– assessing the effect of their condition(s) on their patient’s duties and vice versa (i.e., the effects of their duties on their condition(s)).

If nothing else, this topic would also explain why ADF patients are more administratively complex (i.e. bureaucratic) than civilian cases.

In addition, MO induction education and training should also include awareness of the health FICs as follows:

- Organisation.36 This is especially relevant to the ADF’s reserve health officers, some of whom are unaccustomed to working in environments where healthcare is not the primary focus.

- Personnel. This refers to expanding the scope of this paper by explaining why and what the ADF seeks from its health officers besides their clinical expertise.

- Collective training. Although this perhaps is not required until entrants join their first health centre or clinic, it can provide a baseline for them to build on.

- Facilities. Although most fixed ADF health facilities are essentially the same as their civilian counterparts, consideration could be given to awareness of the ADF’s deployable facilities and their capabilities.

- Supplies. This entails education regarding their role (whether medical, dental, nursing, pharmacy or other allied health) with respect to ensuring that the right amounts of the right items (and their spares) are provided to the right place(s) at the right time(s) and that they are in-date, remain sterile, maintained within the cold chain and/or properly serviced.

- Major systems. This refers to using the ADF’s health information technology systems for tasks such as patient records, telehealth, casualty regulation and medical store management.

- Civilian industry support. This refers, in particular, to education as to why as well as how to use the clinical expertise that is only available from the civilian health system, without abandoning the military aspects of managing (not just treating) ADF patients.

- Other support. This only need entail education regarding of the various forms of non-clinical health support provided by other ADF elements. Potential examples include providing ship’s first aid parties for Navy, and engineering services for deployed Army and Air Force health units.

- Command and management. This entails education as to why as well as how the health command and administrative processes interact with each other, and with the relevant commanders.

This education and training can be achieved by a single albeit highly modularised ADF Health Officer Induction Course (HOIC), which would fill the knowledge gaps in the current and provide a common baseline for subsequent courses. The HOIC should be conducted at the end of the single-service military induction training and should be brief enough (no more than two weeks) to facilitate the greatest possible face-to-face participation by reserve and permanent health officers. It should include common elements for the aforementioned topics, with breakout sessions for the different health professions and single-service groups.

As it should clearly explain why as well as how the ADF health services are a small part of a much larger organisation for which healthcare is not its primary focus, the HOIC should be conducted at a Canberra venue such as the Australian Defence Force Academy (rather like the ADF Chaplain’s College) rather than a health-only location such as HMAS Penguin, Bandiana or Richmond. This would not only allow briefs and lectures by the relevant Joint Health Command (JHC), single-service health directorates and Joint Operations Command (JOC) health staff, but also the relevant non-health ADF elements who interact the most with the health services, such as the single-service career management agencies, and commander designate course staff. It would also allow DVA representatives to explain what they need from ADF health personnel, for the latter to fulfil Butler’s ‘facilitate civilian transition’ mission. These education components preclude exclusively relying on computer-based training or other forms of distance learning.

MO recruiting and retention

It should be apparent by now that the clinical expertise that MOs bring to the ADF on entry only constitutes a baseline: besides additional clinical training for the ‘treatment service’ mission, they also require education regarding the ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions. It is therefore unclear how this can be addressed by only addressing their conditions of service per Project DUNLOP,37 given the ongoing mismatch between what the ADF’s current MOs want to do versus what the ADF needs them to do to fulfil Butler’s missions. Explaining this mismatch partly pertains to how MOs are currently recruited, requiring some historical background.

The ADF conducted multiple MO recruiting and retention studies from the mid-1970s to the early 2000s.38 These studies coincided with multiple efficiency and economy reviews, 39,40,41,42,43 which essentially ignored the ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions. These studies instead identified a lack of clinical training opportunities, in the context whereby entering MOs with any postgraduate qualifications into the permanent ADF has continued to average perhaps one per service per 10 years, at least since the 1980s.

Hence, the ADF’s current permanent MO recruiting practices have almost exclusively been based on facilitating Primary Health Care (PHC) training via the RACGP and the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACCRM).44 Meanwhile, the ADF’s secondary and tertiary specialist clinical requirements were only partly met by reservists, which led to the Medical Specialist Program being introduced in 2014.45

Although this model fulfilled some of the ADF’s ‘treatment service’ mission requirements, it also continues to target its recruiting efforts on MOs who will leave as soon as possible to pursue civilian clinical careers: this at least partly explains the current post-Return of Service Obligation (ROSO) rate of about 10% per annum (i.e. around one MO per service per year). This is becoming unsustainable as the RACGP places more onerous limitations such that its Defence registrars spend less time seeing ADF patients. Furthermore, besides not meeting all the aforementioned PHC ‘treatment service’ mission requirements the ADF needs, this model fails to enable the other functions and roles necessary to fulfil the ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions.

Broadly speaking, the ADF has two options to resolve this issue. One is to ascertain how many O4 and O5 MOs it needs to conduct all three missions, accept the current post-ROSO retention rate, and increase the number of PHC MO entrants accordingly. This would mean the ADF would reliably obtain four or five years of employment before they separate, which would increase the deployable MO pool, make it easier to staff base health clinics where finding contractors is difficult and make it worth providing additional non-clinical medical education and training such as the HOIC. However, this option still does not facilitate the depth of expertise ADF MOs need to fulfil their ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions. It is also inconsistent with the current ‘garrison’ health support model, which for the last 25 years has been premised on employing contract civilian APS and contractors in the base setting rather than uniformed MOs.

The second option would instead entail Defence redirecting its MO recruiting efforts towards non-RACCGP/ACCRM candidates. These would still provide primary healthcare alongside their PHC peers to begin with, but move to facilitating the other two missions as part of their normal civilian career progression in due course. To this end, the aforementioned ADF population factors explain why ADF patients do not always need the full range of GP-level PHC services, and that most of those they do need are for work-related musculoskeletal and mental health conditions.46,47 Furthermore, as previously explained, the ADF needs MOs whose PHC roles entail the following skills additional to providing clinical treatment:

- Assessing how their patient’s job affects their health, and how their health limits or stops them from doing their job as intrinsic to their routine PHC for every ADF patient they see. This would fulfil their ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian transition’ mission and their ‘treatment service’ mission.

- Providing—and later managing—workplace-based rehabilitation (thereby fulfilling their ‘treatment service’ and ‘operational capability’ missions).

- Facilitating compensation (thereby fulfilling their ‘civilian transition’ mission).

- Implementing—and later designing—workplace health promotion programs to prevent work-related illness and injury (thereby fulfilling all three missions).

These tasks would, in turn, support systemic health research into work-related illness and injuries to inform ADF health policy development, thereby establishing a feedback loop to make ADF workplaces—including those in the deployed setting—healthier and safer. Besides providing targeted treatment services for a workforce population, doing so would also reduce the preventable workplace illness and injury costs incurred by Defence and DVA, enhancing ADF operational capability.

Besides the ‘general ADF’ population, these activities also need to be conducted for its Specialist Employment Classification (SPEC) subpopulations, such as aircrew, submariners and divers, noting these comprise a surprisingly large proportion (about 15%) of the ADF workforce.48

Therefore, it seems reasonable to assert at this point that the medical specialties whose civilian career progression is most compatible with all three ADF health services missions are Occupational and Environmental Physicians (OEPs) and Public Health Physicians (PHPs). While admittedly simplistic, one of the differences between these two specialties is that PHPs focus on the general population, while OEPs focus on workforces. A more important differentiation, however, is that although both specialities consider the environmental effects—including workplaces—on a target population’s health, OEPs also consider vice versa, i.e. health-related suitability for workplaces. This explains why the ADF needs to prioritise recruiting potential OEPs.

There are several reasons why this has not occurred: besides the focus on treatment services at the expense of the other two missions, can be added the small size of the civilian OEP and PHP workforces (currently around 500 and 600, respectively, in Australia and New Zealand), and the viability of post-ADF civilian OEP and PHP careers. Even so, the ADF health services do not require large numbers: they only need enough to conduct Butler’s missions.

In addition, rather than health administration qualifications (whose scope is generally limited to administering civilian treatment services),49 the ADF’s PHC MOs should undertake postgraduate occupational and public health diplomas at the O3 level and masters at the O4 level as part of their ADF career progression. However, although several tertiary institutions provide Masters of Public Health (MPH) courses, at present, this is not so for occupational medicine. Hence, as an operational capability enabler, Defence should consider funding a university (as it did the Centre of Military and Veteran’s Health for some years from the early-mid-2000s) to establish occupational and environmental health diploma and masters courses based on their existing MPH courses.

Although these added requirements may give pause to candidates who only see Defence as a short-term employer en route to their definitive civilian GP career, focusing on recruiting prospective OEPs and PHPs should not only improve overall MO retention but also provide additional skill sets the ADF needs beside those required to treat patients. Ascertaining the number of permanent ADF PHC and OEP/PHP practitioners should be premised on:

- Identifying the number of O5 and O6 OEP and PHP practitioners required to conduct all three missions, which can be used to determine the number of O3 and O4 trainees required to sustain them. Although it will take time to ascertain their retention rate, it seems reasonable to assert that the closer alignment between their service and civilian employment should make it better than their PHC counterparts’ 10% per annum.

- Using the current 10% per annum historical PHC MO retention rate to ascertain how many O3 entrants would be required to fill the remaining O4, O5 and O6 PHC MO positions.

Finally, it should be noted that this approach has considerable potential to create synergies between future co-located ADF PHC trainees and practitioners and their OEP and PHP colleagues.

Conclusion

There has been a longstanding misperception within Defence and elsewhere, that its health services only need to provide treatment services. This fails to recognise the other two missions necessary to support military workforces rather than civilian populations: enabling operational capability and facilitating their eventual transition to the civilian community.

The previous series explained why excessive workplace illness and injury rates confirm the need to improve the management of hazards associated with ADF workplaces, with better emphasis on prevention. Figure 1 summarises these papers by showing the relationships between ADF operational capability, the three health service missions that support that capability, the eight health service functions and roles that enable those missions, and the nine FICs they need to conduct those functions and roles. It also demonstrates the extent to which occupational and environmental health is intrinsic to all the components of a truly holistic military healthcare system.

This paper explains why the health ‘personnel’ FIC is not fit for purpose in its current form regarding ADF MOs (and, by extension, other health officers). Besides neglecting the ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions, the focus since the late 1990s on recruiting those intent on civilian GP careers has precluded providing all the PHC services required for the ADF workforce.

Hence, consideration should be given to the following:

- Establishing an ADF HOIC, to educate (not just train) permanent and reserve members in the functions and roles they must perform to fulfil Butler’s missions, and the FiCs that sustain them. As this entails clearly articulating what the ADF needs as opposed to what its current health staff want (especially given their role within an organisation in which healthcare is not its primary focus), this course should be conducted at a Canberra venue, to include the relevant non-health headquarters, directorates, and other agency speakers, as JHC, JOC, the single-service health directorates, and DVA.

- MO recruiting should be re-prioritised to entice more candidates to undertake the OEP and PHP specialties, thereby enabling the ADF’s health services ‘operational capability’ and ‘civilian re-integration’ missions as part of their normal career progression. These candidates will still be required to provide PHC services for ADF members during their training.

- MO entrants intent on PHC careers be required to undergo diploma-level population health education, additional to their RACGP or ACCRM training, for promotion from O3 to O4, followed by master’s training for promotion to O5. This will require liaising with suitable tertiary institutions to establish the relevant diploma and masters courses in public health and (in particular) occupational medicine.

It is suggested these proposals are consistent with the meaning of the word ‘joint’ as described by the then CDF in 2017, as applied to the ADF health setting:

‘I look at where we’ve come to now from back then [1999] and we are well ahead, with a far better understanding that joint isn’t doing everything the same. Joint is about bringing the best of the three services and the public service together to get the best combination you can for that particular operation.’ [underlining added].50

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the RAN, the ADF or any other organisations mentioned.

Corresponding Author: Neil Westphalen, neil.westphalen@bigpond.com

Authors: N Westphalen11,2

Author Affiliations:

1 Royal Australian Navy – Directorate of Navy Health

2 University of New South Wales Canberra at ADFA