N Westphalen

Introduction

This article follows previous papers by the author regarding occupational and environmental medicine in the ADF.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10

These articles, as well as a 2019 Productivity Commission inquiry,11 explain why high workplace illness and injury rates confirm the need to improve the management of hazards associated with ADF workplaces, with better emphasis on prevention. To this end, a submission by the Royal Australasian College of Physicians to the aforementioned inquiry advocated this would best be achieved by basing the ADF’s health services on a systems-based occupational health strategic model.12

Doing so would require reassessing the fundamental inputs to capability (FIC)13 for both Joint Health Command (JHC) and Defence’s Work Health and Safety Branch. The current state of the ADF’s occupational and environmental health services, and the small number of civilian specialist practitioners within the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (AFOEM), suggest that a mature holistic and sustainable model would take 10–15 years’ sustained effort.

This article expands on these papers, regarding what Colonel Arthur Graham Butler referred to in his official WWI medical history as the ‘allegiances’ of military health services, and how, in today’s parlance, these can and should be considered their elemental and enduring ‘missions’.14

Biography15

Arthur Graham Butler was born at Kilcoy, QLD, on 25 May 1872, the son of station manager William Butler and his wife June (née Graham). He studied at Cambridge in the UK for a Master of Arts (1894), followed by medicine and surgery (1897, 1899) before entering general practice at Kilcoy and then Gladstone. He left Gladstone in 1907 for 12 months’ postgraduate study at the University of Sydney and began a specialist obstetric and gynaecology practice in Brisbane. He also became the honorary secretary of the Queensland branch of the British Medical Association or BMA (precursor to the Australian Medical Association) from 1912 to 1914.

Having entered the Australian Army Medical Corps (AAMC) in 1912 as the Moreton Regiment medical officer,16 Butler joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as a captain on 20 August 1914. He was appointed regimental medical officer to the 9th Battalion, whose officers and men quickly nicknamed him ‘Gertie’. Besides referring to his older age, the name suggests they believed his medical preparations excessive, whereas his biographer (probably quite rightly) called them ‘meticulous’.

Butler’s actions during the Gallipoli campaign belied their moniker. He was in one of the first boats ashore at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915; was evacuated sick in July; returned a month later and remained until the withdrawal in December. Having been promoted to major, Butler was the only Australian medical officer to win the Distinguished Service Order during the Gallipoli campaign for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in attending casualties under heavy fire.17

In February 1916, Butler was appointed the I Anzac Corps Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Services (DADMS), a role he continued after arriving in France in April. It entailed supporting the corps Assistant Director (Colonel Courtenay Clarke Manifold, Indian Medical Service), whose role was ill-defined but generally entailed coordinating his divisional Assistant Director subordinates’ activities. Further to his writing talent inherent to having a MA, it should be noted that this also enabled Butler to gain useful staff skills from an administratively experienced medical officer, which were otherwise generally lacking within the AAMC at the time.

Butler was promoted to lieutenant colonel in November 1916, and given command of the 3rd Field Ambulance in February 1917. It was employed as the 1st Division’s main dressing station until September when it took over the Menin Road advanced dressing station. Having been twice mentioned in dispatches, Butler was sent to the AIF headquarters in London in May 1918 to help collate its medical records. He then commanded the 3rd Australian General Hospital at Abbeville as a colonel, from July 1918 until it closed in June 1919. After another six months at the AIF war records section, Butler was demobilised in February 1920, whereupon he resumed his Brisbane private practice and became the State BMA president.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Graham Butler, London, 191819

3rd Australian General Hospital, Abbeville, 23 June 191820

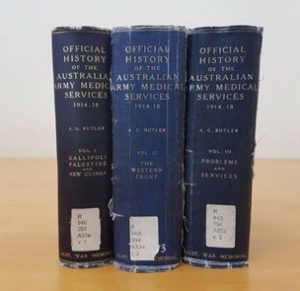

In 1923, Butler was persuaded to write the official history of the wartime AAMC. This task occupied the next 20 years of his life, for which he gave up his practice and moved to Canberra. Having written all except those parts of the first on the German New Guinea campaign, and the RAN section of the third, his three-volume history was published in 1930, 1940 and 1943. In seeking to isolate and analyse important problems as a guide to future medical health policy and management, Butler’s history has been considered one of the English-speaking nations most distinguished war histories.22

Dr Arthur Graham Butler and Dr Allan Seymour Walker (official WWII medical historian), Australian War Memorial, 19 June 194523

Butler died in Canberra on 27 February 1949, and was buried in St John’s Baptist Church in Reid, Canberra. He was survived by his wife Lillian and daughter Joan (wife of Air Vice Marshal Sir Valston ‘Val’ Hancock).24 A colleague said of Butler, ‘he was everything that gentle upbringing, the highest education, Christian philosophy, unbounded comradeliness, fearless integrity, the zeal of an idealist, and boyish humour and enjoyment of life could make a man’.25

Butler’s ‘allegiances’ and their relevance to military health services

For this paper, Butler’s description of what he termed the ‘allegiances’ of military health services are worth quoting in full (underlining added):

‘As we follow the course of the casualties, sick and wounded, from the front through the various levels of evacuation to their distribution and final disposal, and examine the system, whereby, in the last years of the war, temporary “wastage” from the front and loss of strength through present “unfitness for service” were reduced to their minimum and the morale and health of the force maintained, we find three prime purposes intermingling in the manifold activities of the medical service, each related to a specific responsibility and mandate. To the military command, it owed service to promote and conserve man-power for the purpose of war. To the nation at large, it was responsible for promoting by intelligent anticipation the efforts of the civil institution whose duty it should be to prepare for useful return to civil life the soldiers unfitted for further military service. By Humanity, as represented by the nations who had subscribed to the International Convention of Geneva and the Hague, it was charged with minimised so far as possible the individual sufferings of the combatants of both sides. These three strands of purpose, inextricably interwoven as they were, in a self- contained and consistent scheme of medical service nevertheless furnished each as an end in itself—all three entering at every stage into the medical problem, and now one, now another, providing its dominating motive.26

This paper is premised on the following.

- Butler’s wartime experiences, as a decorated battalion medical officer, field ambulance and general hospital commander, and staff medical officer, ensure his credibility as a military clinician and administrator, attributes he shared with many of his

- However, unlike his contemporaries, Butler spent much of his life writing a well-regarded history that comprehensively analysed the AAMC’s activities during WWI, and the enduring elemental lessons to be learned

- The aforementioned quote represents an encapsulation of these lessons, which Butler referred to as the three ‘allegiances’ of military health

- Despite Butler’s intentions, the lessons he identified have since been lost, not least by subsequent Australian official military medical 27,28,29

- 80 years later, Butler’s ‘allegiances’ would now be referred to as military health service ‘missions’.

The rest of this paper analyses Butler’s ‘allegiances’ and the extent to which they continue to represent the elemental and enduring missions of today’s military health services in general and the ADF health services in particular.

Butler’s humanity ‘allegiance’: the treatment services mission

Butler notes that military health services owe an ‘allegiance’ to humanity, to minimise as much as possible the suffering endured by military personnel. Notwithstanding the advances in clinical care since, this mission in itself is no different to civilian health services, especially given the overlap with some casualty evacuation and most military humanitarian aid/disaster relief (HA/DR) and operations.30

However, a primary distinction is that civilian health services have no remit regarding the military operational capability or civilian transition missions. Furthermore, previous articles describe how military health services are differentiated from their civilian counterparts, in that the population they provide care for is (by definition) exclusively working age, while most of their clinical conditions (in particular musculoskeletal and mental health disorders) are either caused by their work, or affect their ability to perform their work.31,32

These articles also note that even in peacetime, ADF members can often be exposed to a variety of physical, chemical, biological, ergonomic and psychosocial workplace hazards. To these can be added combat- related workplace hazards deliberately intended to cause harm, in the form of weapons such as small arms, grenades, mortar and artillery rounds, sea-, land- and air-launched missiles, sea and land mines, and torpedoes, which can cause death or injury secondary to penetrating wounds, blunt trauma, blast injuries and/or burns. Nuclear and other radiological weapons pose additional physical hazards, as do biological hazards from weaponised bacteria, viruses and toxins, and chemical hazards from weaponised blistering, choking and nerve agents.33,34

These considerations explain why even in peacetime, Butler’s wartime humanity ‘allegiance’ would now be referred to as the military health services’ ‘treatment mission’, while the work-relatedness of the illnesses and injuries requiring treatment justify why these services ought to be based on a broader systems- based occupational health strategic model.

Butler’s military command ‘allegiance’: the operational capability mission

Butler notes that military health services also owe an ‘allegiance’ to commanders to promote and conserve personnel for the purpose of war. To this end, he also wrote (underlining added):

‘Most writers who deal with the part of medicine in the war tacitly accept as a postulate—as it is also a matter of general belief—that the one essential feature of the work of the medical service in the late war was to bring about a greatly diminished incidence of disease. As will be shown, close study of facts and figures makes clear that this attitude must be modified. The many problems associated with civilian participation in military activities on the one hand, and with the reinstatement as civilians of the wastage from warfare on the others, will be found to open up in the chapters of this section. They do so along two lines—positive, in the vast domain of ‘reparative’ treatment, surgical and medical; and negative, in the only less arduous and exacting work of the military boards and the military machinery for implementing the system of “category”.35

It should be noted Butler wrote extensively elsewhere regarding the role of sanitation, vector control and related health services, and the role of military dental services in enabling military operations by reducing preventable disease and non-battle injuries.36,37

Butler makes a key point noting that the scope of personnel conservation not only entails returning injured and sick personnel to normal duty where possible. He also refers to the need for a robust medical categorisation process that keeps commanders informed of their personnel’s health status to maximise their utilisation in achieving their mission(s).38,39 Besides articulating the role of the current ADF Medical Employment Classification System and its antecedents as personnel rather than patient management tools, Butler presciently anticipated the RACP’s Position Statement Health Benefits of Good Work, and its applicability in the ADF health setting.40

However, this paper contends that the operational capability mission is far broader than simply providing the treatment and preventive medicine services required to conserve personnel. It must be remembered that Butler’s experiences reflected an especially grim form of industrial-scale attrition warfare, for which preserving personnel strength as an end unto itself proved essential to victory. The same could also be said of the WWI campaigns in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and East Africa, and the WWII Burma and Southwest Pacific campaigns, where the key component to operational success pertained less to managing combat casualties than controlling overwhelming rates of preventable disease.41.42.43,44,45 This and previous papers explain why the scope of the ADF’s preventive medicine services should also include non-combat workplace injuries.

Rather, another key yet under-recognised component of the operational capability mission is to facilitate additional flexibility to commanders as to how they can achieve their operational tasks than they would have otherwise. For example, the scope of medical CBRN defence is not limited to simply preventing and treating such casualties but also enables operations to continue despite ongoing CBRN threats.46 For a somewhat less fraught peacetime example, although the health services for Operation BEL ISI II in Bougainville from 1997 to 2003 were perhaps clinically under-employed, their contribution to operational capability just by ‘being there’ should not be underestimated. Besides enhancing operational flexibility in achieving the commander’s peace monitoring mission, their presence also helped maintain personnel morale at the tactical level and the broader community, media and hence government support for BEL ISI II at the strategic level.47 Finally (but by no means less importantly), military health services also render feasible physiologically demanding operations, such as those pertaining to the ADF’s aviation, diving and submarine capabilities.48

Even so, despite undertaking clinical work at Duntroon from 1927 to 1930, Butler seems not to have recognised the extent to which his military command ‘allegiance’ extends beyond combat operations, most likely because the Australian Army at that time—including its medical services—was almost exclusively based on a part-time militia force that was not required (and in fact legally unable) to deploy overseas.49 This should be compared with health support for Navy’s peacetime overseas operations at that time, to locations where shore- based health services were simply not available within an operationally or clinically appropriate timeframe.50

These considerations explain the contention per previous papers that, even in peacetime, all military health services at all levels have a role in facilitating every commanders’ mission (irrespective of whether it entails being deployed). Hence, the military health services’ ‘enabling operational capability mission’ likewise necessitates a systems-based occupational health strategic model. However, these papers have also referred to the outgoing SGADF’s comments per the 2019 Graham Shirtley Oration, indicating ADF commanders remain dissatisfied with the health support they receive.51 This paper contends that a primary reason pertains to the lack of consideration given by JHC and its DHS predecessor to this mission, especially regarding operational activities that do not entail deployment. This, in turn, reflects longstanding misperceptions within JHC and elsewhere within Defence regarding the true scope of this mission and (in particular) how much it costs, without also recognising the cost to operational capability, of not performing them. Furthermore, the fact that many ADF members conduct operational roles without necessarily deploying, also explains why their enabling health staff should likewise be under military discipline.52,53,54,55,56

Butler’s civilian community ‘allegiance’: the civilian transition mission

Finally, Butler notes that military health services owe an ‘allegiance’ to the nation at large to facilitate the civil institutions responsible for returning military personnel deemed unfit for further service to the civilian community. For more than a century, the primary institution he referred to has been the Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA), and its antecedent organisations.57 However, previous articles and the aforementioned Productivity Commission inquiry have highlighted the need for substantial reform, particularly regarding rehabilitation and compensation.58,59,60,61

It should be noted that Butler began writing his history at a time when the ‘Repat’ provided services for hundreds of thousands of ex-AIF members with war-related illnesses and injuries and that many ‘Repat’ service providers themselves had wartime experience. Among other factors, this meant that the latter could, for example, ‘fill in the gaps’ when reviewing each claimant’s often scant wartime clinical and other documentation, perhaps decades later. Post-WWII ‘Repat’ assessors also possessed this capability in the 1980s, many of whose wartime service was comparable to ‘Repat’ claimants.

However, the tribulations endured by Vietnam War veterans indicate the extent to which their assessor’s wartime experience had to be relevant to that of their claimants. Furthermore, the issues faced by Gulf War and subsequent veterans demonstrate how DVA assessors became and remain unable to ‘read between the lines’ regarding each claimant’s clinical and other documentation where it exists. The claims process is further hampered by the exclusion of occupational physicians, despite their specific training in assessing clients, providing impartial advice regarding their eligibility and treatment, and facilitating their return to work.62,63

This limitation highlights why it is essential that all ADF personnel—not just the medically separated ill and injured members referred to by Butler—should be managed as potential DVA clients from when they first join. However, previous articles explain why the current organisational split between the clinical services provided by JHC, and the reporting of those illnesses and injuries deemed work-related to the Defence Work Health and Safety Branch, is actively inimical to achieving this mission.64,65 This situation is not improved by largely bureaucratic rehabilitation processes that lack specialist rehabilitation and occupational physician clinical input and have no outcome measures do not include their success in actually returning ADF members to normal duties.66 These organisational deficiencies further support the contention that the military health services ‘civilian transition mission’ requires a systems-based occupational health strategic model.

Butler’s ‘quo vadimus?’ (‘where are we going?’): a false choice

Having reiterated his ‘allegiances’ at the beginning of his third volume epilogue, Butler concludes:

‘The Army Medical Service seems to be at the parting of the ways. One road might lead it to complete devotion to purely military ends—the winning of war at any price. If that happened, the task of keeping alive the principle of humanity and of safeguarding the social interests of the State and the individual would be left more and more to the voluntary and civil organisations [as referred to elsewhere in his epilogue, which would now be referred to as non- governmental organisations or NGOs]. On the other hand, in spite of the military commitments to ruthless warfare, it may retain its triple responsibility. Which way it goes must depend on the extent to which medicine, regarded as a social group, tends to give its souls as well its body to the ideal of “total ruthlessness”, or (on the other hand), to co-operate with social influences in maintaining the humane ideal… towards which homo sapiens has slowly, painfully but bravely climbed from the primeval jungle.’67

Unlike his ‘allegiances’, Butler’s perception that military health services face a binary choice between military versus humanitarian needs has since attracted attention.68,69 Once again, it must be recognised that his rather despairing verdict was written during another worldwide cataclysm, which frequently saw the perversion of medical science for the perpetration of evil, over and beyond the previous conflict. Furthermore, it should also be acknowledged that such threats to Butler’s treatment ‘allegiance’ remain extant.70,71 However, the recent inquiry into alleged atrocities by Special Air Service Regiment personnel demonstrates the need for military health services to be actively engaged with operational commanders to prevent, or at least belatedly publicise, such incidents.72 To these can be added their ability to support HA/DR operations in higher- threat environments where NGOs cannot work73 and support good work for peacetime operations.74

In short, Butler’s ‘quo vadimus’ question represents a false choice: rather than isolating medical services from potential war criminals, the most challenging aspect of military medicine pertains to balancing his ‘treatment’ allegiance against the other two missions—not only for humanitarian purposes as ends unto themselves, but also to facilitate operational capability by assisting commanders to prevent such crimes (and if necessary, bearing witness should this fail), as well as reducing long- term mental health issues among their personnel by ameliorating the more egregiously preventable horrors of war.

The interaction between these missions

Butler notes that the ‘allegiances’ he refers to are not discretely separate, but intrinsically linked depending on circumstances. By way of an elemental demonstration, let us consider a typical ADF primary health care presentation. Besides the normal clinical process of taking a history, examining the patient, performing investigations, formulating a diagnosis and prescribing treatment (i.e. the ‘treatment mission’), Defence clinicians also need to consider the following for each ADF patient.

- The ‘operational capability mission’. This entails considering whether or not the diagnosis and/ or treatment limits or prevents the patient’s ability to perform their normal duties, or vice versa, that is, whether their normal duties will affect their diagnosis or If they do, consideration needs to be given to how either or both affects their commander’s mission. For example, losing the lead Air Battle Manager (ABM) in a Wedgetail crew to illness will require substantial changes in personnel management if he or she is unfit to fly, compared to another ABM with the same diagnosis who is not assigned to flying duties. Furthermore, it will also change their clinical management and prioritisation if the patient in question is the only available ABM for a particular mission.

- The ‘civilian transition mission’. This entails careful documentation as to how and why the patient’s illness or injury Although assessing work-relatedness can be straightforward, this may not always be the case, especially for conditions such as mental health disorders, whose clinical effects resulting from work-related exposures and vice versa may not be readily apparent. Besides documenting work-related illnesses or injuries for future treatment liability and compensation purposes, this component of the care provided also needs to be fed back into preventing future cases, thereby directly influencing the other two missions.

Besides demonstrating how these missions are intimately linked, this example also explains why military health services have a significantly greater level of complexity than other health organisations that only have one mission, and accounts for the greater bureaucracy inherent to providing care for ADF patients compared to civilians. However, as previously indicated, at present JHC’s ‘treatment mission’ is the only one to be recognised as such, and resourced accordingly, by the ADF and broader Defence and other government institutions.

Besides demonstrating how these missions are intimately linked, this example also explains why military health services have a significantly greater level of complexity than other health organisations that only have one mission, and accounts for the greater bureaucracy inherent to providing care for ADF patients compared to civilians. However, as previously indicated, at present JHC’s ‘treatment mission’ is the only one to be recognised as such, and resourced accordingly, by the ADF and broader Defence and other government institutions.

Conclusion

With ADF personnel arguably exposed to the most diverse range of occupational and environmental hazards of any Australian workforce, high rates of preventable workplace illness and injury indicate the need to improve the management of occupational and environmental health hazards, with better emphasis on prevention than treatment.

This paper contends that Arthur Graham Butler’s history represents 20 years of historical analysis that identified what would now be referred to as the three elemental and enduring missions of military health services. Although Butler understandably describes them from a post-WWI Army perspective, this paper asserts that, although their implementation may differ, these missions remain relevant today to all three services in both peace and war. Butler also explains why military health services are inherently far more complex compared to their civilian counterparts. Therefore, it is unfortunate that only one of the missions identified by Butler is recognised as such and resourced accordingly.

These considerations explain why health care for military workforces should be provided by practitioners who are themselves under military discipline. They also support the contention that, in order to perform all three of the missions identified by Butler, the ADF’s health services should be premised on an occupational-health-based systems model, with revised FIC that would lead to a genuinely holistic, sustainable and fit-for-purpose health services over the next 10–15 years.

Future articles will describe the FIC necessary to sustain the functions and roles described in previous articles in order to enable these missions.

Author

Dr Neil Westphalen graduated from Adelaide University in 1985 and joined the RAN in 1987. He is a RAN Staff Course graduate and a Fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and the Australasian College of Aerospace Medicine. He also holds a Diploma of Aviation Medicine and a Master of Public Health.

His seagoing service includes HMA Ships Swan, Stalwart, Success, Sydney, Perth and Choules. Deployments include DAMASK VII, RIMPAC 96, TANAGER, RELEX II, GEMSBOK, TALISMAN SABRE 07, RENDERSAFE 14, SEA RAIDER 15, KAKADU 16

and SEA HORIZON 17. His service ashore includes clinical roles at Cerberus, Penguin, Kuttabul, Albatross and Stirling, and staff positions as J07 (Director Health) at the then HQAST, Director Navy Occupational and Environmental Health, Director of Navy Health, Joint Health Command SO1 MEC Advisory and Review Services, and Fleet Medical Officer (2013–2016).

Commander Westphalen transferred to the Active Reserve in 2016. Comments regarding this and previous articles are most welcome.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the RAN or any other organisations mentioned.

Corresponding Author: Neil Westphalen, neil.westphalen@bigpond.com

Authors: N Westphalen 1,2,

Author Affiliations:

- Royal Australian Navy Reserve, Directorate of Navy Health

- University of New South Wales Canberra at ADFA, Student, School of Humanities and Social Sciences