INTRODUCTION

The Australian Policy Handbook, by Peter Bridgman and Glyn Davis, was “designed for those who become embroiled in the sometimes turbulent world of public policy…”.1 Given the substantial changes to the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF’s) health services in recent years, it seems worthwhile comparing the Australian Policy Cycle, as described by Bridgman and Davis, with the processes used by the Defence Health Services (DHS).

This article is based on an essay written in mid-2002 for a Master of Public Health. It includes an overview of the Australian Policy Cycle, using examples of health policies developed by the Defence Health Service Branch (DHSB). Its perspective stems from providing Senior Health Officer (SHO) feedback on draft DHSB policies and implementing them later on. Notwithstanding a lack of personal experience in working at Campbell Park, it is a valid exercise to compare DHS processes, as seen by an Area Health Service (AHS) SHO, with those described in The Australian Policy Handbook.

For the purpose of this article, ‘DHS’ refers to the ADF’s three Defence Health Services as a whole, while ‘DHSB’ refers to that part of the Defence Personnel Executive located in Canberra, that is responsible for strategic ADF health policy.

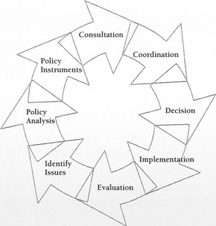

Figure 1. The Australian Policy Cycle

THE AUSTRALIAN POLICY CYCLE AND DHSB

Bridgman and Davis’s Australian Policy Cycle is summarised in Figure 1. Although it has eight steps, many of these can be (and often are) undertaken concurrently. Issue Identification.1 The Australian Policy Cycle typically starts with identifying an issue requiring either a new policy or changes to an existing policy. Issues identified as suitable are then placed on the policy agenda for action. Bridgman and Davis suggest this process entails making political judgements based on discussions with ‘interested parties’, which can be divided into external and internal agencies. In the DHS’s case, examples of external agencies which may participate in the issue identification process include:

- CHANGES IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS. The initiation of the war against terrorism led HQAST to convene a Theatre Health Planning Group (THPG) to develop a health support plan for deployed ADF forces. Having been represented at the THPG, the joint Health Support Agency QHSA) should then have developed its own plan for ADF members who are deploying to or returning from this operation. It is understood that, in practice, JHSA had to develop its own health support plan to support HQAST, before the latter could develop its own plan.

- LEGAL ISSUES. Changes to the Privacy Act in late 2001 led to debate within AHS-WA (and presumably elsewhere), regarding possible changes to DHS’s clinical information management processes. These changes were reflected in JHSA’s Directive 2/2002, which describes how this legislation is to be applied by NSA health staff.

- OTHER GOVERNMENT AGENCIES. The 1996 Australian National Audit Office (A NAO) report on ADF health services recommended that DHSB establish the level of health services required for ADF operations while rationalising non-operational health support.

Examples of agencies within DHS include:

- SENIOR HEALTH STAFF. A high priority for the previous SGADF was a policy on medical research ethics, which is now promulgated as DI(G) ADMIN 24-3.

- RESERVE ADF MEDICAL SPECIALISTS. Discussion between DHSB and the Burns and Plastic Surgery Health Consultative Group led to a draft health directive on skin photography, which went through several iterations before release.3

- FINANCIAL CONSIDERATIONS. An overspend on the antismoking drug Zyban led to Health Bulletin 1n000 to control its use for ADF personnel. This led to a reduction in Zyban expenditure of about 80%.

- AHS SHOs. SHO feedback from JHSA Conferences since February 2001 has led to changes being made to several Health Directives.

Bridgman and Davis stated that an issue needs four criteria to make it onto a policy agenda. This is illustrated by a DHSB decision in 1998 to vaccinate ADF personnel against Japanese Encephalitis (JE):

- AGREEMENT THAT A PROBLEM EXISTS. Although JE is a risk for some deployed ADF personnel, it took some effort for DHSB to accept that naval personnel were at much less risk and therefore did not require vaccination.

- THE PROBLEM NEEDS TO BE FIXABLE. In this case, a vaccine against JE was available.

- THE PROBLEM FITS THE POLITICAL CONTEXT. For JE vaccine, key issues were that:

- Its use was consistent with DHSB’s focus on operational deployability per the 1996 ANAO report.

- Whether naval personnel should receive it in the interest of consistency across all three services, as opposed to actual clinical need.

- Whether the problem is important enough to require action. In this case, the risk of death or disability from JE to some ADF personnel was considered high enough to proceed. However, the 10% incidence of systemic adverse reactions6 militated against its use in a low-risk seagoing population.

In the end, a satisfactory outcome was reached for naval personnel regarding the use of JEV, following the necessary interactions with the senior maritime health providers.

Policy Analysis. Bridgman and Davis show that policy analysts typically work their way through the following sequence:

- FORMULATING THE PROBLEM. This stems from issue identification.

- DEFINING OBJECTIVES AND GOALS. For DHSB, this is typically achieved by applying it’s strategic out comes (health-related force preparation, casualty prevention and treatment, and health capability management and development) to the issue for incorporation into its business plan.

- IDENTIFY DECISION PARAMETERS. DHSB parameters typically include deployability, legal and funding concerns. In some cases, the parameters come from outside DHSB. An example was the development

of Dl(G) PERS 1 1S, regarding a new Medical Employment Classification (MEC) system, for use not only by health staff but by workforce planners and career managers. - SEARCH FOR ALTERNATIVES. This entails research, using sources such as other jurisdictions and journal articles. Key issues for DHSB include the relevance of Australian civilian practice to the military context. This was seen in a draft Health Directive on STDs dated August 2001, whose application in its then form seemed not only likely to be problematic in the operational context but also did not address the administrative follow up required for a highly mobile military population. Furthermore, a process for tracking STD cases in the deployed military context seemed not to have been considered at that time.

- SOLUTIONS. As only one draft solution is usually circulated for further consultation, a problem for DHS is a lack of visibility outside DHSB as to whether all alternative solutions have actually been identified.

The policy analysis tools available to DHS encompass those discussed by Bridgman and Davis as follows:

- ECONOMIC ANALYSIS. This includes cost-benefit, cost-effective and opportunity cost analyses. Cost benefit analyses uses dollars to measure which policy option will deliver the most benefit. Cost-effective analyses recognise that cost-benefit analyses may not result in valid comparisons so that some options remain viable on other than economic terms. Opportunity costs analyses indicate the extent to which selecting one policy option means forgoing another. Although DHSB performs some economic analysis, it appears to have little or no visibility regarding opportunity costs and appears to focus on cost-benefit rather than cost-effective analyses. It is suggested this has been demonstrated by the effort expended on some outsourcing reviews.

- SOCIAL FRAMEWORK. This includes the consequences of particular policy options for minority groups and/or the institutions required to provide services. The DHSB social framework is focussed on individual fitness for operational deployment while ensuring that non-operational ADF health services are comparable to the civilian Medicare system. It is unclear, however, whether this focus on deployability is entirely compatible with the perception by some ADF personnel (reinforced by recruiting brochures) that they have an entitlement to ‘free medical and dental’ services, which implies that ADF health care is or should be benchmarked against the private health system. It is, therefore, not surprising that the expectations of some ADF personnel are sometimes not met.

- ENVIRONMENTAL FRAMEWORK. This considers the environmental impact of a particular policy, usually via an Environmental Impact Statement. This is not normally a significant DHS issue but may have to be considered when developing health policy for application in the seagoing environment as well as ashore. The environmental framework may also be the primary focus for NBC, aviation and underwater medicine policy and is of direct importance in occupational medicine policy.

- LEGAL FRAMEWORK. A particular concern for JHSA relates to indemnity issues that limit the use of civilian contractors for non-operational health services, such as medical coverage for airfield emergencies.

Bridgman and Davis also discussed two policy analysis models developed by Charles Lindblom. His ‘rational’ policymaking model attempts to clarify the objective(s) that a policy needs to achieve, through analysis of discrete means versus ends. The analysis per this model is comprehensive and takes every relevant factor into account, but often relies heavily on theory. According to this model, the test of a good policy lies in how well it meets the stated objective(s). This model is generally used when contemplating significant change.

On the other hand, Lindblom’s ‘incrementalist’ policymaking model recognises that the objective(s) that a policy needs to achieve is often not clear-cut and that means and ends are often indistinct. As the selection of the goals and the action required are interlinked, the analysis relies on a succession of comparisons with similar policies, thereby reducing the reliance on theory. According to this model, the test of a good policy depends on how various analysts agree on a policy, without necessarily agreeing that it is the best way to meet an agreed outcome. This model is generally used when contemplating gradual change.

In recent years the ADF has tended to apply Lindblom’s ‘rational’ model to a variety of management processes, rather than his ‘incrementalist’ approach. The limitations of the former are illustrated by the 1996 ANAO report as, for example, it is possible that, because the analysis was not perhaps as comprehensive as it needed to be, the theoretical savings in DHS personnel and other costs may not be achievable. The difficulty with the latter model is that it may not be appropriate if radical changes are required. Having used Lindblom’s ‘rational’ model in recent years to instigate radical change throughout the DHS, it is suggested that his ‘incrementalist’ model is more appropriate in consolidating those changes.

Policy Instruments. Bridgman and Davis define policy instruments as the means used by governments to achieve their ends. Good policy advice relies on using the right instruments for the right policy. Bridgman and Davis cited Hood (1983) in describing four types of policy instruments as follows:

- ADVOCACY. Policy instruments such as publicity campaigns argue a case rather than force a result. These are rarely used by DHSB, although one possible exception was the introduction of the 1-800-IM-SICK number.

- FUNDING. These instruments control policy funding rather than the policy itself. DHSB examples include the use of funding controls to manage Zyban and to use contractors to overcome constraints on its own staff and/or time.

- GOVERNMENT ACTION. This refers to providing public sector services, as demonstrated by the decision that DHSB should focus on the provision of health services for operational units as per 1996

ANAO report.2 - LAWS. These establish a framework for government action, although much of the detail is contained in regulations. As a military organisation, DHS relies heavily on this type of policy instrument. These range from standard operating procedures at the unit and AHS level, to plans and instructions from JHSA and HQAST, to Defence Health Directives and Defence Health Bulletins from DHSB. These are in turn subordinate to Defence Instructions and other instruments approved by CDF, in accordance with the Defence Act (1903) and extant government policy.

Bridgman and Davis describe the criteria used to select the best policy instrument for a particular policy, such as:

- EFFICIENCY (or whether this instrument will be cost-effective). For example, draft DHSB policies on

skin photography and refractive surgery during 2002 led to resource concerns that resulted in further review. On the other hand, the Zyban health bulletin has proved a cost-effective solution. - EQUITY (OR FAIRNESS). For example, the restrictions on the wearing of contact lenses are generally applied to all personnel, even though the care of contact lenses at sea is less problematic than for austere ground deployments. This suggests that DHSB has been concerned with equality of treatment of ADF members (apart from special groups such as aircrew, submariners, divers, parachutists, and SF personnel), at the expense of equity with respect to RAN members.

- WORKABILITY (OR WHETHER THE INSTRUMENT CAN ACTUALLY BE IMPLEMENTED). As the JHSA health sup port plans for Ops SLIPPER and RELEX were derived from those used for land-based operations such as TANAGER and BEL ISI, their application to seagoing personnel was found to duplicate extant processes and did not reflect actual requirements to prepare RAN members for these two deployments.

Consultation. Bridgman and Davis explained the need to test a preferred choice with the wider community. Although consultation improves the quality of the policy, it is expensive in time and resources. A good example of the time and effort in ensuring consultation was the report on a new career and remuneration structure for ADF MOs, which took 21 months to complete instead of the expected three.’ Although improvements to the DHS consultation process via JHSA have allowed Area Health Service SHOs to provide feedback on draft health policies, this has also occurred at the expense of additional time and effort.

Bridgman and Davis cited Shane and Amberg (1996:21), who suggested that there is a continuum of consultation instruments, including:

- INFORMATION. This typically refers to marketing, usually via surveys and focus group research. DHS typically limits this consultation instrument to using contractors for data collection.

- CONSULTATION. This instrument solicits views from relevant people and groups. DHSB has typically used this consultation instrument in the final stages before a policy is approved, although advice has recently been solicited from SHOs in the early stages of an initiative to rationalise ADF policy on convalescent leave.

- PARTNERSHIP. This draws the community into the decision-making process, typically by representation on advisory committees. DHSB has a very wide range of working groups, steering committees and consultative groups to provide health policy advice. Although the concept appears sound, it is unclear how often or how effectively this advice is utilised.

- DELEGATION. This shifts policy responsibility elsewhere, for example by holding a public inquiry which becomes responsible for dealing with a particular problem. DHSB has had occasion to delegate policy responsibilities (typically involving implementation issues) to JHSA and/or HQAST, sometimes with insufficient reference to resource issues.

- CONTROL. This occurs when a community makes a policy choice, for example by referendum. DHS does not use this type of instrument, although the introduction of the DHS logo in 2001 is an occasion where it may have been appropriate.

Bridgman and Davis described how, in order to remain focussed, consultative processes should have clear terms of reference, timelines and outcomes. These processes were considered by Davis (1996: 22-24) (cited in Bridgman and Davis 1) as follows:

- PURPOSE. Consultation may be necessary either to improve the quality of the policy processor to achieve consensus. Since January 2001, JHSA, in particular, has expended considerable effort on consultation to improve transparency and accountability.

- METHOD. Consultative processes typically use a range of instruments to spread the range of opinion. DHSB however mostly relies on group processes.

- IDENTI FYING STAKEHOLDERS. DHS attempts to identify particular individuals with a known level of interest and/or expertise for its consultations. This can be ‘hit and miss’ initially but typically improves over time. An example was a meeting in March 2002 regarding aeromedical evacuation, which discussed (among other things) which participants were needed for future meetings on this issue.

- BEGINNING CONSULTATION. This has been referred to previously regarding issue identification. Sometimes the first intimation to SHOs that a particular policy was being considered has been when a draft policy was released by DHSB for comment.

- CONSULTING WITH INDIVIDUALS AND GROUPS. Consultation overload and time constraints are a concern when several draft policies are concurrently released by DHSB for comment. This is a particular concern in the lead up to the DHS Steering Committee meetings where policies are tabled for approval.

- COMPLETING THE CONSULTATIVE PROCESS. A particular problem for DHSB is a lack of feedback to participants regarding the outcome of their input, generally because of resource constraints. A partial solution has been the use of follow up correspondence after the policy is released, as part of the next policy cycle.

- CONSULTATION ‘TRAPS’. This term refers to special interest groups, which may not be representative of the community as a whole. It is suggested that DHSB has few problems managing special interest groups within Defence, as the role of staff in representing their particular organisation is usually clear and unambiguous.

Coordination. Bridgman and Davis stated that governments strive to institutionalise coordination through appropriately designed policy structures. As many DHS policies are for internal use, the need for coordination with other agencies may appear to be minimal. There are occasions however when DHSB provides advice to other authorities within Defence. DI(G) PERS 16-15, on the new MEC system, is a good example, as it not only affected DHS but the three single service career managers, workforce planners and other authorities. Conversely, JHSA has requested the Defence Legal Service to review indemnity issues for civilian contract health staff and to advise on the application of privacy legislation to NSA health staff.

Decision. Bridgman and Davis described the decision point as the time when the work of the policy analyst is judged through a regulated process. Draft policies are presented for approval at the DHS Steering Committee, which replaced a rather ad hoc approval process in January 2000. This meets approximately every two months, with Committee members receiving the proposals four (until recently only two) weeks beforehand. Following discussion, proposed policies may be approved, recast, sent back for further review or abandoned by DGDHS. This process, therefore, incorporates senior-level health consultation and may include discussion on the policy analysis, use of appropriate policy instruments, coordination and implementation issues.

The three main problems with the current process are:

- READING TIME. The reading time was recently expanded from two to four weeks; however, it remains to be seen whether even this is sufficient for multiple and/or complicated proposals.

- MATERIAL VOLUME. The volume of material at the meeting, as the Committee not only discusses up to a dozen policies but also deals with health budgeting and other issues.

- POLICY PRIORITISATION. Some policies receive higher priority from the Committee than others because of their relative ease, level of individual or political interest, or because they resolve a high profile but trivial problem, at the expense of day to day issues involving all ADF health facilities. This reflects the issue identification stage of the cycle discussed previously.

Implementation.‘ Bridgman and Davis (1998) describe how policy is meaningless without implementation and that this needs early consideration by policy analysts. They cited Lewis Gunn (1978), who described ten conditions for perfect implementation per Figure 2:

TEN CONDITIONS FOR PERFECT POLICY IMPLEMENTATION (GUNN, 1978)

- No crippling external constraints.

- Adequate time and resources

- A suitable combination of resources at each stage.

- A valid theory of cause and effect.

- Direct links between cause and effect.

- A single implementation policy, or at least a dominant one.

- Understanding and agreement on the objectives to be achieved.

- A detailed specification of the tasks to be completed.

- Perfect communication and coordination.

- Perfect obedience.

Figure 2

It can be seen that, for various reasons, these conditions may not apply to the DHS (or indeed anywhere else in Defence).

Bridgman and Davis1 also noted Howlett and Ramesh (1995: 154-55) and Lindblom (1980:65ff) and discussed two forms of implementation instruments:

- Non-coercive forms of action. Examples used by DHSB include contracts and expenditure controls.

- Coercive forms of action. Examples used by DHSB include administrative directions through Health Directives and Bulletins.

Howlett and Ramesh (1995: 154-55) were also cited by Bridgman and Davis1 as stating that policy implementation is affected by:

- The nature of the problem.

- The diversity of the problem

- The size of the target group

- The extent of behavioural change required.

These considerations were demonstrated by the new MEC system. During the initial implementation period, multiple ADF authorities continued to use their own interpretation of the new system, based on the nature of how particular clinical problems affect them, at a time when a large degree of behavioural change was required by all participants. These problems resolved as they became more familiar with the new process.

DHSB also has to contend with many of Lindblom’s ‘Implementation Traps’ per Figure 3. This particularly refers to incomplete specifications, conflicting objectives (such as ‘world’s best practice’, which may or may not apply to a military clinical environment) and inadequate administrative resources for the tasks at hand.

LINDBLOM’S IMPLEMENTATION TRAPS

- Incomplete specification.

- Inappropriate agency.

- Conflicting objectives.

- Incentive failures.

- Conflicting directives.

- Limited competence.

- Inadequate administrative resources.

- Communications failures.

Figure 3

Finally, it should be noted that although DHSB has accepted responsibility for policy development, its implementation has been delegated to JHSA and HQAST. As this split in the policy cycle isolates DHSB from the organisations that use the policy it generates, it is suggested this does not facilitate accountability for the end product (i.e. whether the policy actually works or has unforeseen outcomes) from either DHSB or its subordinate organisations.

Evaluation. Bridgman and Davis describe evaluation as the point at which a new cycle of analysis begins to confirm, adjust or abandon current policies. Evaluations tend to follow a standard format, beginning with terms of reference and followed by an evaluation strategy, data collection, consultation and analysis. As this reproduces the overall policy process, the latter becomes iterative. This process is used by DHSB to identify issues for further action.

Although there has been considerable criticism of many new policies that have been developed by DHSB in recent years, it should be noted that many have involved major surgery to extant processes while at the same time trying to meet the needs of a customer base that had undergone major structural changes. In the final analysis, at some point it becomes necessary to release a new policy despite known imperfections, in order to address immediate problems. Improvement to these policies is only possible by trying them out, identifying the problems and having a process to address them. It should be noted that many of the policies discussed in this article have not yet gone through their second iteration. Policies that have done so, such as the Health Directives on infertility management and voluntary sterilisation, demonstrate DHSB’s ability to address problems with the extant policy.

CONCLUSION

Comparison of DHSB’s policy processes with The Australian Policy Handbook indicates a high degree of consistency with the Australia n Policy Cycle. Issues are identified for consideration and are analysed by DHSB staff for potential solutions. These are matched to a limited range of policy instruments, draft versions of which are released for consultation. Coordination issues are addressed at a senior level before approval by DGDHS. Many steps in this cycle occur concurrently. If nothing else, it is suggested that Bridgman and Davis go a long way to explain the complexities, potential for conflict and frustrations felt by many if not most participants who are involved with the development and implementation of useful and relevant ADF health policy.

It should also be noted that in recent years OHSB has developed many new policies that so far have only been round the cycle once. It is suggested that the quality of ADF health policy can only be properly assessed once it has been developed, implemented, assessed, revised and implemented again. This would entail going twice ’round the buoy’. The need for subsequent iterations would then depend on the general rate of policy change within Defence and how these changes impact on the DHS.

However, DHSB’s main deviation from the Policy Cycle occurs at the implementation stage, as this has been the responsibility of subordinate organisations. This makes evaluating the success or otherwise of policies difficult and does not facilitate either accountability or getting issues onto the OHSB policy agenda for the next cycle. It is suggested this can only be resolved either by making DHSB responsible for policy implementation as well as development, and/or ensuring that the parties who are responsible for implementation (i.e. JHSA and HQAST) have the resources to do so.