Introduction

During the Vietnam War, Agent Orange (AO) or 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin was utilised for military purposes.1 It is assumed that Vietnam Veterans were exposed to AO. US research on the adverse effects of AO on the human body started during the Vietnam War in the 1970s. Exposure to AO is associated with increased cancer risk,2 immune deficiency, reproductive and developmental defects,3,4 central and peripheral nervous system pathology, bronchitis, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, skin rashes, hypertrichosis, hepatotoxicity, hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia.5,6 Many studies have evaluated the AO exposure and risk of prostate cancer in US veterans, but none have assessed its effect on Australian veterans.7 Hence the authors conducted a systematic review to assess the quality of evidence for AO and its association with prostate cancer.

Methods

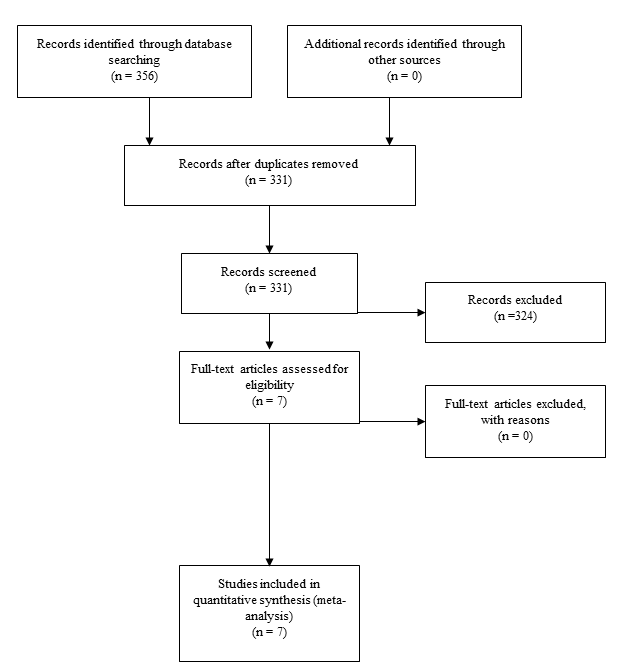

Study protocol

In performing our systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines where possible.8 We performed a systematic search through MEDLINE (from 1950), PubMed (from 1946), EMBASE (from 1949), Current Contents Connect (from 1998), Cochrane library, Google Scholar, Science Direct and Web of Science to 1 August 2022. The search terms included ‘Agent Orange, 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-para-dioxin and prostate cancer,’ which were searched as text word and as exploded medical subject headings where possible. No language restrictions were used in either the search or study selection. The reference lists of relevant articles were also searched for appropriate studies. A search for unpublished literature was not performed. The reviewers were not blinded to the authors and institutions. The authors conducted the literature search, study screening and data extraction.

Study selection

We included studies that met the following inclusion criteria:

- Studies identifying the population of patients exposed to Agent Orange and developing prostate

- Studies with extractable data were included in the meta-analysis.

Exclusion criteria:

- Reviews, letters and

- Studies without extractable

Studies deemed irrelevant to the research question due to lack of focus on prostate cancer, lack of relevance to the Vietnam War or veterans.

Studies were excluded from the final meta-analysis if they failed to quantify the apparent incidence of prostate cancer and only discussed other factors such as PSA or other risk factors.

Quality of the studies

For non-random controlled studies, a modification of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used as an assessment tool for selection, comparability and outcome assessment.9 Study quality was rated on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 9 (high). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. This has been summarised in table 1.

Table 1. Study characteristics

| Author | Year | Country | Study type | Prostate cancer exposed | Agent Orange exposure | Prostate cancer unexposed | No exposure | Agent Orange-exposed men age (years) | Unexposed men age (years) | Newcastle – Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamie et al.2 | 2008 | USA | Cohort study | 239 | 6214 | 124 | 6930 | 59.7 | 62.2 | 7/9 |

| Zafar et al.37 | 2001 | USA | Retrospective study | 13 | 32 | 33 | 96 | 60.4 | 65.5 | 6/9 |

| Giri et al.16 | 2004 | USA | Case-control study | 11 | 28 | 29 | 135 | 55 | 56 | 7/9 |

| Ansbaugh et al.26 | 2013 | USA | Cohort study | 74 | 203 | 822 | 2517 | 60.6 | 65.0 | 7/9 |

| Yi et al.21 | 2013 | Korea | Postal survey | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5/9 |

| Akhtar et al.25 | 2004 | USA | Retrospective study | 36 | 281 | 54 | 1517 | 45.5 | 43.5 | 6/9 |

| Pavuk et al.40 | 2005 | USA | Case-control study | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6/9 |

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature search stratFegy.

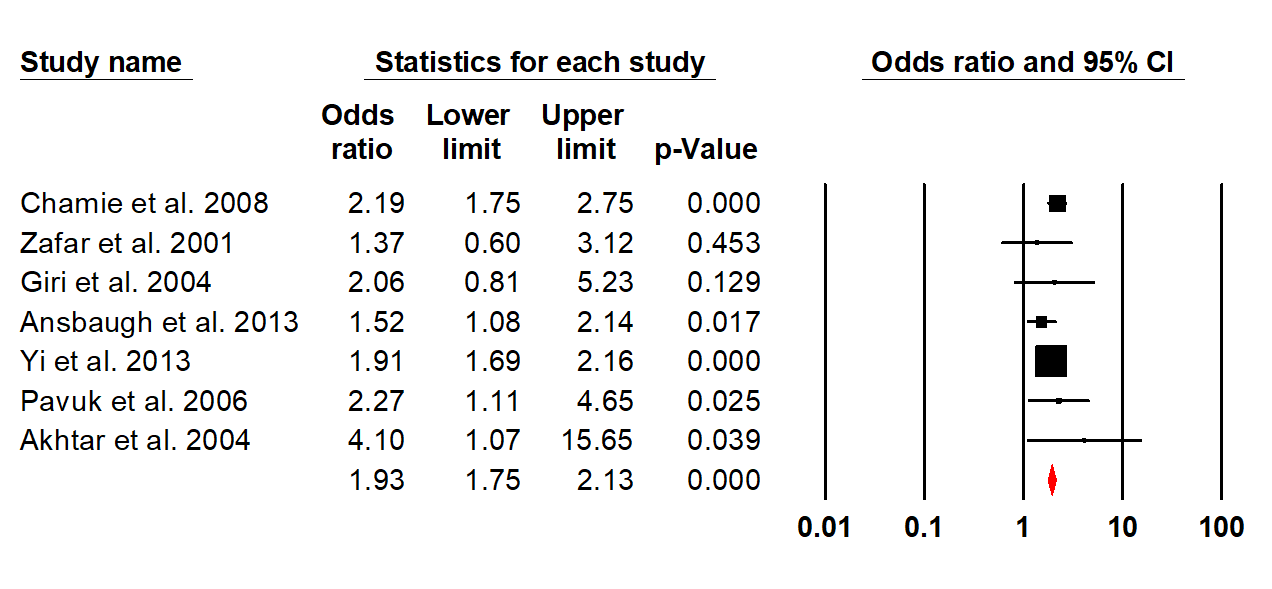

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the relationship between Agent Orange and prostate cancer.

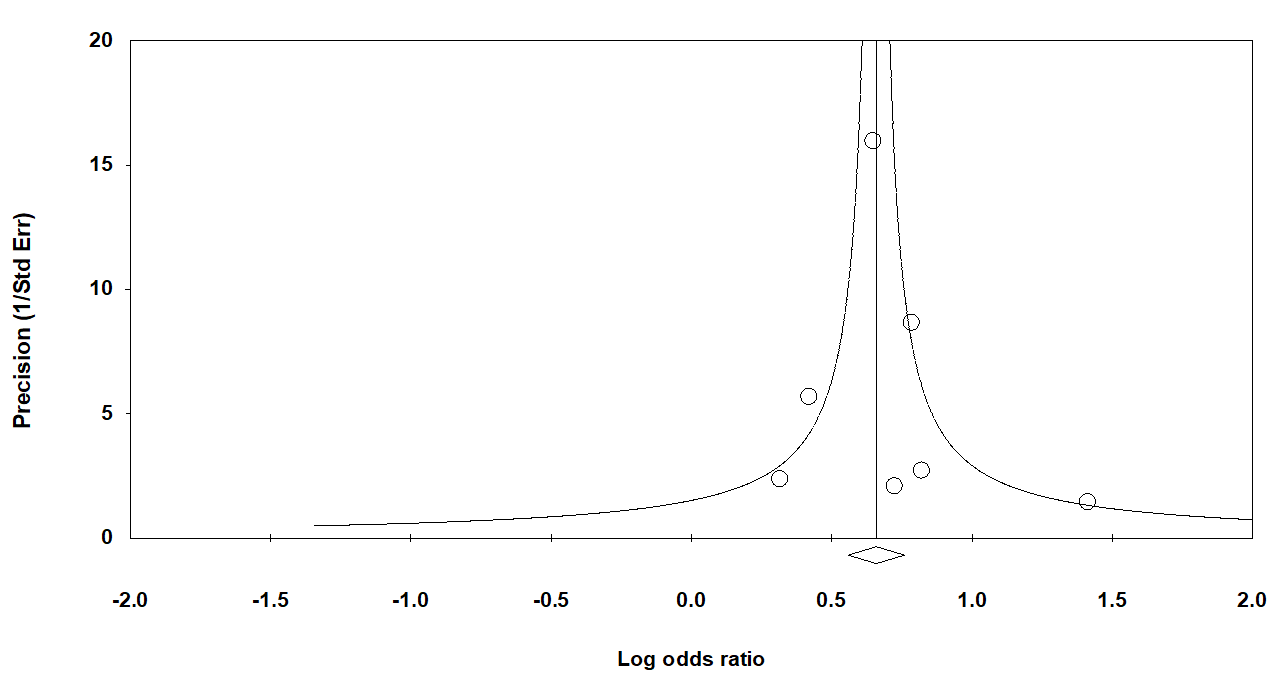

Figure 3. Funnel plot assessing publication bias.

Data extraction

We performed the data extraction using a standardised data extraction form, collecting information on the publication year, study design, number of cases, total sample size, population type, country, continent, mean age and clinical data. The event rate and confidence intervals were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Pooled event rate and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird).10 We tested heterogeneity with Cochran’s Q statistic, with P <0.10 indicating heterogeneity, and quantified the degree of heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which represents the percentage of the total variability across studies which is due to heterogeneity. I2 values of 25, 50 and 75% corresponded to low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively.11 The quantified publication bias using the Egger’s regression model,12 with the effect of bias assessed using the fail-safe number method. The fail-safe number was the number of studies we would need to have missed for our observed result to be nullified to statistical non-significance at the P <0.05 level. Publication bias is generally regarded as a concern if the fail- safe number is less than 5n+10, with n being the number of studies included in the meta-analysis.13 All analyses were performed with Comprehensive Meta-analysis (version 3.0), Biostat, Englewood, NJ (2014).

Results

The search recognised seven studies that were included in the meta-analysis as these had extractable data.14-20 The pooled odds ratio for prostate cancer was 1.93 (95 % CI: 1.75-2.13). No (0%) heterogeneity was detected among the studies, confirmed by the test for heterogeneity being not significant (P =0.52). Moreover, no publication bias was detected using the Egger’s regression model (P = 0.82). It was also observed that veterans developed prostate cancer earlier than non-veterans (58.37 years vs 61.23 years), but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.42).

Discussion

AO was a commercially synthetic defoliate sprayed widelyallthroughthe Vietnam War. AOwasadulterated with the toxin 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, a recognised carcinogen. Satisfactory evidence has linked AO to several other malignancies, including soft tissue sarcoma, Hodgkin’s disease and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma.21-23

Prognosis and natural history of prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is presently the most common malignancy and the second leading cause of mortality among men in the US.24 Akhtar et al.25 observed an amplified occurrence of prostate cancer in exposed individuals compared with unexposed controls serving in Southeast Asia during a similar era. Our meta-analysis suggests that AO exposure increases the risk of developing prostate cancer by approximately twofold. A recent study26 suggested an amplified risk of prostate cancer associated with AO and an increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer in men who undergo an initial prostate biopsy. They also observed that the veterans with AO who were at risk for having high-grade prostate cancer detected presented with abnormal prostate screen findings and, on average, had cancers detected 4 to 5 years earlier than nonexposed veterans. Another study2 reported an association between AO and high- grade prostate cancer among 363 men with prostate cancer in a population-based study of US veterans. These findings may have noteworthy inferences in developing effective prostate cancer screening policies for veterans exposed to AO because they may develop more life-threatening cancers earlier than veterans never exposed or males in the general US population. Similarly, Shah et al.27 suggested that among men who elect radical prostatectomy, AO exposure could be linked with more aggressive prostate cancer. However, AO exposure did not statistically impact survival in a multivariate analysis of veterans.28

In an Australian study, Wilson et al.29 found a borderline increase in the death rate of Australian soldiers exposed to AO in the Vietnam War with a Standardised Mortality Ratio (SMR) 1.23 (95% CI 0.99, 1.46). Wilson et al.30 observed 25% elevation in the number of prostate cancer cases when compared to the community (P <0.001), having observed 692 cases. Although these studies provide insight into Australian data, we could not include these in our meta-analysis due to a lack of extractable data.

Another theory of note was that the increased incidence of Vietnam Veteran prostate cancer rates may be due to higher rates of PSA and subsequent prostate cancer diagnosis. Alternatively, it could also be argued that military personnel undertake more frequent health check-ups.30

Screening strategies

Two large randomised trials have assessed the usefulness of screening for prostate cancer and found somewhat contradictory outcomes.31,32 The role of AO has not been sufficiently investigated in Australia. This meta-analysis suggests that there should be further research in this area. So far, only a few articles have been published33-35 and one good case-control study.36 Consideration should be given to classifying this group of veterans as ‘high risk’ in a similar approach used with patients with a family history of cancer. Research indicates that veterans exposed to AO at a younger age have higher Gleason scores and a greater probability of metastatic disease.2,16,21,25-28,37-41 The contemporary evidence supports screening these veterans for prostate cancer to detect high-risk cancers before metastases develop. However, new screening programs present additional pressures on the healthcare system. In order to incorporate this into the screening program, there is a need to document more evidence in the form of prospective studies, especially in Australian veterans.

Corresponding Author: G.D. Eslick guy.eslick@sydney.edu.au

Authors: A. Dossetor1, V. Nagaraja2, G.D. Eslick3

1 Bond University, Gold Coast

2 The Mayo Clinic, USA

3 CLUED Pty Ltd, Sydney