T Sorić, I Gusar, A Zekanović, I Vidić, B Dželalija

Introduction

Relevant literature mentions exposure to war events as a significant factor in the emergence of not only mental but also physical illnesses.1–3 Enormous effort is being put into finding new and better ways of treatment while, at the same time, efforts are expended on the development and acquisition of weapons and other material that could cause disease and adverse health outcomes. The Homeland War in the Republic of Croatia was fought between 1990 and 1995, and it is estimated that over 500 000 soldiers fought in the war.4,5 Croatian defenders can unquestionably be singled out as a particularly vulnerable group due to long-term and serious consequences of war-related sufferings.6 The available data in Zagreb City Office for Health and War Veterans state malignant neoplasms as a leading cause of death among war veterans between 2006 and 2011.6 Furthermore, the research on disease incidence and mortality of the general population conducted in Zadar County in 2005 puts malignant neoplasms in second place, just after leading cardiovascular diseases,7 but the research on the veteran population is deficient. Wartime events always cause a large amount of stress8–10 associated with the emergence of malignant neoplasms.11 It is well-known that hormones such as cortisol, norepinephrine and adrenaline, which are released during stressful situations, change the immune status of the body and the ability to fight cancer.12 Thus, psychological and neurophysiological occurrences in the body are crucial for immune system functioning or the ability of the body to efficiently cope with stressful situations.12,13

Many former studies have investigated the impact of stress on cancer emergence,14–16 but there is a lack of research investigating the consequences of stress occurring during war and the impact of cancer on active war participants. Carcinoma is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality of people worldwide. Cancer incidence is a leading public health problem both in Croatia and worldwide, and the number of newly-discovered cases is constantly increasing.17–19 Despite the implementation of primary prevention, which includes preventive measures, secondary prevention plays an important role. Specifically, secondary prevention implies early detection of cancer, which is achieved by actively looking for people affected by cancer amongst a seemingly healthy population.20 This type of prevention includes adequate, highly sensitive and specific methods of screening, accessible and acceptable to a broader population.20 In recent years, an increase in men affected with urogenital tract cancer has been noticed in Croatia.19,21,22 Several studies show the occurrence of urogenital tract cancer among war veterans.23–25 Therefore, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of prostate, bladder and kidney cancer among the Homeland War veterans of 50–70 years of age in relation to the general male population of the same age in the Republic of Croatia.

With regard to long-term exposure to war, we expect a more frequent prevalence of prostate, urinary bladder and kidney cancer among the Homeland War veterans compared to the general male population aged 50 to 70.

Materials and methods

The cross-sectional study was conducted in Zadar General Hospital, Croatia in the period from 1 March 2017 to 30 June 2018 within the Preventive Physical Examination Program for Croatian Homeland War Veterans.4

Participants

Of the 2101 Homeland War veterans that were processed, 1425 men were included in the research. They fulfilled the following criteria: participants in the Homeland War; participated in the war for more than 1500 days; aged 50–70; and had not previously received treatment for prostate, urinary bladder and kidney cancer.

All Homeland War veterans who met the set criteria were included in the research protocol, which implied: registration of the veterans in the County Office of War Veterans; acquainting the veterans with the implementation of the Preventive Physical Examination Program by the employees of the County Office of War Veterans; registration of veterans in a health institution; registration with the coordinator for the implementation of preventive examination programs in a health institution; informing the veterans on the content and implementation of preventive exams by the coordinator; giving consent and signing written consent / informational consent for the participation in the preventive examination program; giving consent and signing written consent / informational consent for the participation in the research.

Variables

Diagnostic treatment of the subjects included: anamnesis; clinical testing; laboratory tests (prostate-specific antigen, (PSA) + routine blood parameters); ultrasound of the whole abdomen; and transabdominal ultrasound prostate examination. Diagnostic treatment of subjects with suspected prostate cancer in further treatment included prostate biopsy and histopathological examination of the sample.

Diagnostic treatment of subjects with suspected urinary bladder cancer included the use of multilayer computerised tomography (MSCT) and cystoscopy, as well as an endoscopic procedure during which the material for histopathological diagnosis was taken.

Diagnostic treatment of subjects with suspected kidney cancer included additional radiotherapy, MSCT and histopathological treatment of the preparations taken during surgery (nephrectomy, partial nephrectomy).

The control group in the study consisted of men aged 50 to 70, registered in the Bulletin of the Croatian Institute of Public Health ‘Incidence of Cancer in Croatia’21 suffering from prostate cancer, urinary bladder cancer and kidney cancer from the total population of men of the same age as recorded in the Central Bureau of Statistics.26

Bias

The examined group represents only one part of the total number of Home War participants from one Croatian county. It is also possible that in addition to participating in the war, there were other risk factors for the onset of the disease among the subjects. This study could not provide data on causal relationship.

Study size

The number of participants is defined by the number of respondents who are registered in the County Office and have accepted the invitation. The number was also influenced by the duration of the Preventive Physical Examination Program for Croatian Homeland War Veterans.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data have been processed in the Windows Statistics Database (TIBCO Software Inc., 2017). During statistical data processing, the chi-square test (χ2 test) was used to determine whether the received (observed) frequencies deviated from the expected frequencies. In our study, the observed frequencies of the selected diagnoses on the sample veterans aged 50–70 were compared to the expected frequencies of the above diagnosis. The expected frequencies were based on the incidence of prostate, urinary bladder and kidney cancer in men aged 50–70 in the Republic of Croatia. For each of the diagnosis, a separate χ2 test was calculated.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Commission of the Zadar General Hospital approved the research. All participants in the research had previously been informed verbally and in writing of the aim and purpose of the research and voluntarily signed the consent to participate in the research. Anonymity was ensured to the participants during and after the research. Participants can in no way be related to the results of the research

Results

During preventive physical examinations held in the period from 1 March 2017 to 31 December 2018, 2101 men, Homeland War veterans, were examined.1425 (67.8%) participants were in the age group of 50 to 70, while 676 (32.1%) participants were outside the examined age range and were not included in the study.

Out of 52 diagnosed carcinomas, 35 carcinoma sites belonged to urogenital cancers, and 17 newly-discovered cancers fell into other organ systems.

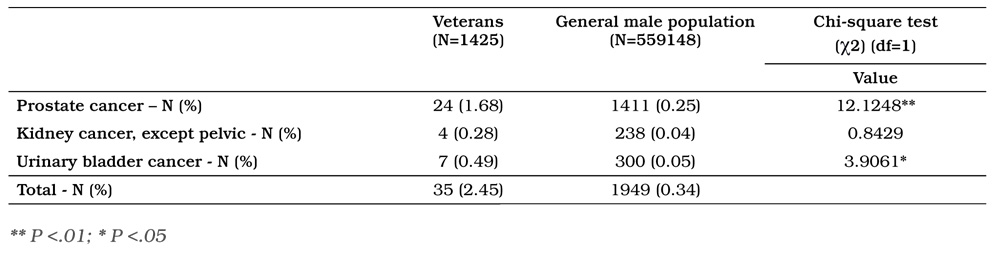

The total proportion of cancer patients was 3.6% (52), while the proportion of patients suffering from urogenital system cancers was 2.4% (35).Of the 35 urogenital system cancers, 24 (1.6%) patients had prostate cancer, 7 (0.4%) patients had urinary bladder cancer and 4 (0.2%) kidney cancer (see Table 1).

Table 1: The number and percentage of diseased veterans and the general male population aged 50–70 and testing differences

The chi-square test (χ2) showed a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of urogenital system cancers between the Homeland War veterans and the general male population of the same age (50–70).The statistical significance of the difference between the prevalence of prostate cancer on the sample of veterans aged 50 to 70 and the prevalence of the same cancer among the general male population in Croatia aged 50–70 is significant χ2 of 12.1248 (df = 1) at a significance level of 1%, which showed more prevalence among Homeland War veterans. The statistical significance of the difference between the prevalence of urinary bladder cancer among veterans aged 50 to 70 and the prevalence of the same type of cancer among the general male population is χ2 of 3.9061 (df = 1) at a significance level of 5%, also more often than the general male population.

The statistical significance of the difference between the occurrence of kidney cancer among the veteran sample of 50 to 70 years and the prevalence of the same cancer among the male population in Croatia is not significant χ2 of 0.8429 (df = 1).

Discussion

The results of our research confirm a statistically significant prevalence of prostate cancer and urinary bladder cancer among Homeland War veterans compared to the general male population of the same age group (Table 1).

Despite numerous research on various topics related to Homeland War veterans in the Republic of Croatia,17,27–29 this is the first medical study on the occurrence of malignant diseases to the best of our knowledge. A limited number of such studies have also been reported in world literature. By comparing our study results to the results of similar research, one observes congruence as well as differences. In both previous research23,24,30–32 and our examined group, prostate cancer appears statistically significantly more often among Croatian veterans than among the general male population of the same age (see Table 1). A survey conducted on Vietnam War veterans investigating the impact of family predisposition and military history on prostate cancer formation highlights family predisposition and exposure to war conditions as risk factors for the development of prostate cancer.31 Furthermore, the results of a Korean Study in 2013,24 carried out by Yi who investigated the connection between carcinoma occurrence among Vietnam veterans, showed there was generally no higher incidence of carcinoma among Vietnam War veterans in comparison to the general population. Contrary to expectations, this research suggests a lower incidence of cancer as compared to the general population, which authors attribute to ‘the effect of a healthy soldier’ indicating a rigorous selection of soldiers. However, in some types of cancer, there is still a higher rate of incidence among Vietnam War veterans in comparison to the general Korean population.24 A higher incidence of carcinoma among the veteran population is related to prostate, urinary bladder and kidney cancer,24 which coincides with our results. Unlike the rigorous selection of Vietnam War veterans before going to war, no selection work was carried out on our respondents before they went to war. All men over the age of 18 were eligible to become defenders. The fact that war-related stress affected our veterans, as well as the concern for their family and home, is an aggravating circumstance. Our results are also consistent with the results of the study ‘Usual Adult Occupation and Risk of Prostate Cancer in West African Men’ conducted in Ghana (West Africa) from 2004 to 2012.32 The aim of this study was to identify occupations where prostate cancer was most common. In the results, the authors associate military occupations with more frequent appearance of prostate cancer.32 Due to territorial proximity, we particularly refer to the research conducted in Italy in 2000 which was triggered by the ‘Balkans syndrome’ media records.

The research included Italian soldiers who were in peacekeeping forces deployed in Kosovo and Bosnia. As a consequence of the use of ammunition containing depleted uranium, they suspected high levels of thyroid cancer and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.33 Although the Italian committee appointed by the Ministry of Defense reported a higher rate of lymphoma and lower rates of other cancers, they did not confirm the correlation with the exposure to depleted uranium.33 Thus, contrary to expectations, the results of the study did not confirm the increased risk for Hodgkin’s lymphoma or thyroid cancer caused by the exposure to depleted uranium among soldiers stationed in Bosnia and Kosovo.33 Despite the negative results of this research, there was still a suspicion of the link between military service in the Balkans and malignant diseases.23 The following study conducted in Norway tested the occurrence of cancer and mortality among Norwegian soldiers who were in the UN peacekeeping forces in Kosovo. Also, as in the previous study, the results did not confirm a higher incidence of cancer in comparison to the general population in Norway.23 However, the same research stated the fact that among the respondents, Norwegian soldiers who had been in Kosovo for more than a year had a greater risk of urinary bladder cancer, which is in accordance with our results. However, this is just an assumption of the author based on three cases and is probably an incidental event of an unknown cause.23 A frequent occurrence of urinary bladder cancer in our study group (see Table 1), can be explained by the influence of known risk factors such as tobacco smoking, frequent urinary infections, long-term use of antibiotics and exposure to certain chemicals.34–36 Although we did not have the relevant data in connection to nicotine addiction of our respondents, we assume that the long-term exposure of Croatian war veterans to war-related stress caused a higher rate of addiction and hence a higher incidence of bladder cancer. Our assumption is based on a survey conducted among American soldiers where cigarette smoking was recognised as a negative strategy of soldiers dealing with stress.36 The above-mentioned research conducted in Italy among soldiers engaged in UN peacekeeping forces in Bosnia and Kosovo did not confirm the frequent occurrence of kidney cancer in the examined group,33 which is in accordance with our results (Table 1).Nevertheless, the research conducted on Vietnam veterans indicated a higher incidence of kidney cancer among veterans compared to the general population that authors associate with the exposure to harmful chemicals.24

Considering the obtained results, we can assume that war and exposure to war events is a strong risk factor for the occurrence of prostate cancer and urinary bladder cancer among male veterans. As active war participants, most often over 1 500 days, Croatian defenders were exposed to a large amount of stress, which many authors in their research consider to be a strong risk factor for many diseases.2,35 Additional duration of stress is considered to be the main cause of physical and mental exhaustion.2 Therefore, Flores et al.connect stress directly with the development of prostate cancer, assuming that it affects the neuroendocrine mechanisms changing genetic material and thus creating the basis for the emergence of malignant neoplasm.3

The lack of our research is evident in terms of comparison of unequal groups of respondents, i.e.comparison of a group of war veterans to the general male population. However, a significant reduction of such deficiency can be observed in the fact that the prevalence of prostate, urinary bladder and kidney cancer among the general male population of 50 to 70 years of age in the Republic of Croatia has been relatively stable in recent years. Furthermore, compared to previously published results of Swedish25 and Danish studies,37 our research does not represent systematic monitoring of the occurrence of carcinoma among veterans, but it is rather a one-time measurement.

The advantage of our research is that it involves a large number of Croatian veterans aged 50 to 70 and mostly uses objective parameters of clinical findings derived from the preventive program rather than questionnaires that respondents fill out based on their own knowledge of their health status. Furthermore, there is a great response of Croatian veterans to physical examinations, which confirms their awareness of the risk they were exposed to. High responsiveness can also be linked with personal care and interest for their own health as well as possible fear of the test results. Additionally, prominent unity and trust among Croatian veterans created in war circumstances, continues in their postwar grouping, which has an important effect on the response to physical examinations.

Despite the former research1,29 on the correlation of war-related stress and the psychological difficulties of the veterans, our results suggest a further need to implement the Physical Examination Plan for Veterans and the need for systematic and detailed monitoring and testing of the connection between organic diseases and exposure to stressful war events.

According to our plans, future research will include the incidence of other types of cancer among veterans and the connection between cancer incidence and the previous inclusion of veterans in supportive psychological programs.

Conclusion

The number of newly-discovered prostate and bladder cancers in the population of Croatian veterans aged 50 to 70 is statistically significantly more common than the number of the same cancers detected among the general male population of the same age group. The exposure of Homeland War veterans to war events and long-term war-related stress is a strong risk factor for the development of prostate and bladder cancer.

Corresponding Author: Gusar, Ivana

Authors: Sorić, Tomislav1,2 Gusar, Ivana;1,3 Zekanović, Anita4 Vidić, Ivan;4 Dželalija, Boris;1,4

Author Affiliations:

1 University of Zadar Department of Health Studies

2 Zadar General Hospital

3 Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Medicine

4 Zadar General Hospital