ABSTRACT

THE EFFICIENT USE OF DEPLOYED PERSONNEL in the Area of Operations (AO) is essential. This often requires personnel to perform tasks beyond the scope of their normal duties. Medical personnel are not immune to this. This paper explores the expanded role for the operational Dental Officer. It does this by:

- determining the criteria under which the expanded role should work, primarily the Dental Officers ability and availability to perform certain tasks;

- exploring the lessons of history;

- examining the training and maintenance of skills necessary to perform the expanded role and, finally,

- discussing the problems associated with an expanded role.

INTRODUCTION

Before any examination of the expanded role of the Dental Officer in the Australian Defence Force (ADF), it first had to be established whether there was a pri¬mary role for the Dental Officer in the Area of Operations.1 This primary role of field dentistry was established by addressing the following questions:

- What are the dental casualty rates in the Area of Operations under various conditions?

- Do these rates affect combat effectiveness/ do toothaches affect work performance?

- Are these rates high enough and their treatment time consuming enough to warrant an operational role for the dentist?

It was only then that the possibility of an expand¬ed role was examined.

The findings of the Mahoney study1 were that:

- Dental emergencies occur at such a rate so as to cause a reduction in the effectiveness of the deployed force.

- Deployed dental assets can return those casualties back to duty, thus maintaining operational capabil-ity and minimising the requirement for evacuation.

Therefore, there is a definite operational role for the dental team. This operational role is important to preserve combat power and as a force multiplier.

THE EXPANDED ROLE CRITERIA

The tasks determined for an expanded role for the Dental Officer would have to meet certain criteria in order to be viable to the ADE Firstly, the Dental Officer must have the time to perform these tasks. If the primary role meant that there was no time to per form additional task, then any thought of an expanded role would be nonsensical. Secondly, the Dental Officer should in the proximity to take advantage of the opportunities of the operational situation (i.e. deployed with assets these tasks relate to). Thirdly, and most importantly, the operational Dental Officer must have the ability to perform these tasks, gained either through their undergraduate or postgraduate training. These skills must be easily maintained and, in the case of postgraduate qualification, easily gained.

THE AVAILABILITY

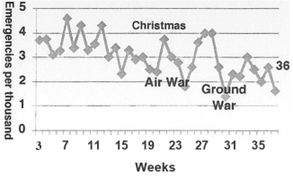

If the dentist is unavailable to perform their allotted task due to the pressures of their primary role, then an expanded role is not feasible. Deutsch and Simecek 2 found in Operation Desert Shield/Storm that, just prior to the action starting, there was a dramatic increase in the rate of dental emergencies and that this figure dramatically decreased at the start of the air and then the ground war. Whilst commanders may believe that troops are ready for battle if they have had there routine checkup, the troops’ major concern is that chronic toothache or broken filling that has annoyed them. This is not unexpected as the troops and their commanders would want to make sure that before action was to start they would be as fit and as pre¬pared as possible. The graph below dramatically illustrates this.

Graph I. The Weekly Rate of Dental Emergencies during Operation Desert Shield/Storm for US Marines.1

The Dental Officers’ primary role of field dentistry reduces just prior to, and at the start of, an offensive. This creates an opportunity to utilise the skills of the Dental Officer in other areas.

THE OPPORTUNITY

Due to their primary role, Dental Officers are regularly deployed with medical assets, from level 2 health care facilities upward.

THE ABILITY

If refresher courses and updates were constantly required, then there would be an adverse impact on the overall dental efficiency within the ADF. The training should not place an onerous burden on the training establishments and resources of the ADF. In considering this, the fact that the vast majority of Dental Officers entering the ADF come from the undergraduate pro¬gram and there is a high turnover of dental officers once their return of service is completed (usually 3-4 years) should be remembered. The initially military training of Dental Officers takes over3 months and, if there were a similar requirement to then become operational, there would be little time in those early years after graduation for the dental officer to become proficient as a dentist.

The end result of having an onerous and overambitious training program would be that either so few Dental Officers would be operationally ready that the Dental Corps could not met the ADF requirements or that the only dentists gaining operational status would become the senior dental officers.

LESSONS OF HISTORY

Perhaps the best measure of ADF Dental Officers’ abil¬ity to perform these expanded tasks is to review what has happened in the past.

Falklands’ War

During the Falklands’ War in 1982, the principle hospital support for the British forces was HMS Canberra. The dentists onboard HMS Canberra, from the outset, were recognised as a resource, which could be used for triage. As a consequence, they were incorporated into the medical team and practiced their drills on the voyage to the Falklands, where it was reported that patients required constant reassessment and updating by experienced well-trained teams. The system worked well and that the success in employing resuscitation trained dental officers in the triage role was particularly worth noting.

Additionally, the surgical centres at Ajax Bay and Fitzroy Settlement had experienced Dental Officers trained in triage and resuscitation techniques. These roles were filled ‘with great success’ by dental officers drawn from the Royal Navy and the Royal Army Dental Corps.3-5

Beirut

On 23 October 1983, at the US Marine encampment around Beirut International Airport, a terrorist bomb packed into a yellow Mercedes truck exploded in the middle of the ground floor of the barracks where 350 marines were quartered. The explosion killed the onshore medical officer and either killed or badly wounded the remaining l2 corpsmen of the medical team.

The initial on-site efforts at the disaster site were coordinated by the two dental officers and a preventive medical officer of the US Navy. A flight surgeon and six corpsmen from USS Iwa Jima and a medical officer from USS Virginia quickly supplemented them. It was these personnel who organised the field first aid station and battalion aid station. It was also this group who performed the first level of triage.

Darwin

In the ADF, there have been incidences where the dental officer has supplied vital life-saving support when the medical support could not. The best documented of these incidences was on a Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ship off the coast of Darwin. At 1800 hrs. on 22 Oct 1985, HMAS STALWART was in company with HMAS PERTH 210 miles (336 km) northeast of Darwin bound for Surabaya (Indonesia). At the time, the Fleet Medical Officer (FMO) and the ship’s Sea King helicopter were in Darwin having Medevaced a sailor with suspected appendicitis.

During a cleaning and transfer operation involving the ship’s bilge, a number of seamen became seriously affected by hydrogen sulphide gas. The senior medical assistant performed immediate treatment and resuscitation. Shortly after, the medical officer from HMAS PERTH arrived. The dental officer had been unaware of the incident and ‘fortuitously’ came into the sickbay at 1935 hrs. At the Board of Inquiry, the dental officer’s actions were described ‘on arrival in the sickbay (he) instilled a sense of order and set about recording casualty details’. His presence was indeed fortuitous as the number of casualties steadily increased after the first medivac. At about 2240hrs, the FMO returned with the Sea King helicopter. It was at this time that the assessment was made that the most affected seamen (4) required aeromedical evacu¬ation to Darwin. On the flight to Darwin were the two medical officers and a number of the sickbay staff. In the end, 59 sailors required medivac to Darwin and 3 sailors (all in the first flight) died. The Dental Officer’s action during the incident received a commendation.8

Other Military Emergencies

In another attack on a U.S. base, Ramstein Air Base in Germany was bombed. The dental clinic was nearby but the base medical clinic and the Army Hospital were not. The airbase dental staff had been trained in wartime medical skills and the clinic had medical supplies for such an emergency. The dental staff provided the immediate casualty care and triage, maintained airways, controlled haemor¬rhages, started IV fluids and prepared patients for transport. Lives were saved and suffering eased by the dental personnel.

During an air show at Kaiserslatern, Germany, two jets from the Italian Air Force demonstration team collided in midair near the centre of the show spreading fuel and debris over spectators. The medical and dental staff on-site provided the immediate treatment of the casualties. “Had the trained dental personnel not been available, the total response force would have been inadequate and additional lives may have been lost.”

Banet states that U.S. Navy dental personnel have successfully responded in times of need as demonstrated by action on the U.S.S. Nimitz and U.S.S. Stark. Dental personnel were also involved the emergency treatment of Pentagon staff on 11 September 2001 following the terrorist air crash.

The lessons of history, therefore, are that:

- Medical personnel are not immune to death and injury.

- Medical personnel in busy times are not always available to deal with unexpected circumstances.

- The dentist and the dental team can assist with medical care with little additional training but this training has to be part of overall disaster-preparedness training.

ADF HEALTH DIRECTIVE 416

The ADF has a Health Directive (HD) on the role of the Dental Officer and reference is made in this to their expanded role. Within these roles, there are a number of well-established tasks dental officers and the medical community are familiar with. These include:

Maxillofacial Surgery. The ability of the Dental Officer to perform some basic maxillofacial surgery is essential. The Dental Officer must be able to surgically remove teeth and perform some basic fixation of frac¬tured maxilla and mandibles so that the patient can be transported to more definitive care, as 25% of dental casualties are maxillofacial or oral surgery in origin.10 On the whole, these skills are gained during their undergraduate years.

Forensic Dentistry. The forensic identification of the deceased has long been recognised as an impor¬tant part of the Dental Officer’s role. Often it is the dental examination alone that can identify victims in war and mass disasters. Dental forensics provide a cost-effective method for identifying the dead.11.12

Health Administration. Senior Dental Officers have long history of providing administrative support in the ADF Health Service.

Decontamination of Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) Casualties. Dental Officers and Medical Officers both have undergone the same basic training in order to be effective decontamination officers.

Other health services taskings as dictated by operational situations. Perhaps the more contentious expanded roles for the dental officers are those that require some postgraduate training and experience. “Depending on the operational circumstances and the qualifications, experience, and training of individual dental officers, those dental officers not required in the previously described duties will be given emergency tasking in such roles as”: (HPD 416.)

- Assisting surgeons in general surgery. All Dental Officers are trained in their undergraduate course in basic surgical and operating theatre skills, such as anatomy, surgery, suturing, and debridement. Therefore, the Dental Officer would be more than capable of providing this support, particularly where trained medical staff are not always available (sickness, injury, away on other duties, etc.). Recently, during deployments to Op Belisi, dental officers were used in this capacity as they were the best person to assist as it was difficult to staff the positions with appropriately trained personnel.

- Assisting anaesthetists, enabling them to manage multiple operations concurrently. The Graduate Diploma in Clinical Dentistry in Pain Control and Sedation has been undertaken by a number of members of the ADF and it has equipped those Dental Officers with the necessary skills to assist anaesthetists. Hence, the continuing involvement of the ADF in this type, of course, is essential, as not only is its course content very closely aligned to the ADF’s needs but it also provides the success¬ful participant with postgraduate recognition. Those skills gained include cannulation, intuba¬tion, Advanced Cardiac Life Support, drug admin¬istration, and recovery management.

- Early Management of Severe Trauma (EMST). Interestingly, EMST is included in the operational role of the Dental Officer in the ADF If the level of EMST training and qualifications are to the Royal Australian College of Surgeons standard, then it is perhaps unworkable for all operational Dental Officers to be trained and maintained to this stan¬dard (it is certainly not beyond the Dental Officer’s capabilities). The commitment required for this type of training is time-consuming and there is an additional problem of the maintenance of skills. This is not to say that Dental Officer should not be trained in EMST. There would be some post gradu¬ate trained Dental Officers whose training and work would lend itself to gaining and maintaining an EMST standard fairly easily. More appropriately, I believe, is that all Dental Officers could be trained to provide advanced life support. Dental Officers, during the initial training in the ADF, have demonstrated that they can be trained in advanced life support and upper airway manage¬ment. This is also supported by the experience with the dentists involved in the Graduate Diploma in Clinical Dentistry. It is believed that because the dentist’s familiarity with the upper air¬ way in their everyday professional life that they are undaunted with its management (Private Communication – Dr D Stewart 2002).

The concept of the expanded role for the Operational Dental Officer is not new; the HD416 has been around since 1996. What is perhaps new is the realisation that the operational Dental Officer can fulfil those roles and that we now have the appropriate training in place. This needs to recognised for a number of reasons; firstly, with the market testing of health services in the ADF and the privatisation of services, efficient use of the available resources is paramount. Secondly, we need to maintain our capability to deal with emergency and operational crises.

TRAINING

Much has been made of this expanded role but, as laid down by the criteria, these skills must be easily gained and maintained. To this end, a number of strategies may be employed to improve the situation.

A New Undergraduate Syllabus. Preference should be given to graduates from universities whose under graduate training best suit the needs of the ADF. While all universities in Australia have roughly the same course outlines, variations do occur and it would be prudent to inform these universities of our requirements as an employer of graduates and under graduates.

Adopt the existing Grad Dip Clin Dent (Pain Control and Sedation). At present, most of the fully trained operational Dental Officers have completed this course and most have done it at their own expense or with the goodwill of the course coordinator. As the graduates of this course are actively using their gained skills on graduation, this course has a distinct advantage in that skills are maintained. Alternatively, the existing Grad Dip could be modified to the exact requirements of the ADF. While the present syllabus is closely aligned to the ADF requirements, some modifications could be made (for example, simulation of battle conditions and injuries). The main advantage of the present Grad Dip is that it is a recognised civilian qualification and skills could be maintained by the Dental officer’s everyday practice. These skills are subject to reassessment and reaccreditation.

Look at ADF requirements and include training in initial officer training. To a degree this is already being done; however, there are problems with the course content being and the need to return the graduate back to their posting.

PROBLEMS

As with any role in the medical fraternity within the ADF, there are problems in retention, maintenance of skills and marketing.

Retention. Skills gained through the ADF are often time consuming and expensive. In order to be competent in the roles of the Operational Dental Officer, some time would have to be spent in the ADF and an even longer time would be required to gain value from the Dental Officer’s training. Retention of skilled members in the ADF is not confined to Dental Officers. This is a force-wide problem and its solution is beyond the scope of this paper.

Maintenance of Skills. This is one of the essential criteria for expanded roles. Those with the Grad Dip Clin Dent find that their skills can be maintaineded through their everyday practice, while others would need to have sessions in operating theatres where the maintenance of their skills could be formalised and recorded.

Spreading the word. Perhaps the greatest obstacle to the expanded role of the dental officer is the ignorance of the general health sector to the Dental Officer’s abilities. Additionally, it must be said that the Dental Officers have their part to play by believing in their own abilities and communicating this to the wider health community and recognising that they are part of the health team.

CONCLUSION

The Dental Officer that is capable of fulfiling their expanded role would be a valuable addition to the Operational Health Team. The Falklands’ and U.S. experience has shown that it is vital that they train and integrate with the medical team and our own experience has shown that they have the ability to perform their expanded role. As it is imperative that the ADF and its health services maximise the available resources at hand, an expanded role for the opera¬tional Dental Officer is essential.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the valuable contributions made by Dr Douglas Stewart, Head of Dept, Oral Medical and Surgical Sciences, Westmead Hospital and Course Coordinator of the Graduate Diploma of Clinical Dentistry in pain control and sedation. Additionally, Captain Timothy Maddern (RAN) and Lt.Col. Steven Curry from ADF Health Services Branch have been most helpful with suggestions and contributions.