Abstract

Although other historical and Biblical figures prior to St Longinus have demonstrated many aspects of a Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I), Saint Longinus is worthy of specific consideration on several levels. To start with, with his seven simple words, ‘Truly this was the Son of God,’ he is the first person to publicly declare the divinity of Christ after his Crucifixion. The tumultuous, joyous and deeply conflicting events of the Crucifixion led to a SW&I that plunged Longinus into a period of nightly terror where he described the lions of doubt, shame and guilt mauled him every night. This is an experience that many modern veterans suffering from a SW&I would understand. To understand the importance of this event as a case study of SW&I, this article begins by developing a background profile of Longinus and then places him in the centre of events of the day of the Crucifixion. Using these and subsequent events in his life, the specific nature of Longinus’ SW&I will be described and potential implications for the modern sufferers of the condition analysed.

Note: For this work, God is defined as ‘a spirit or being believed to control some part of the universe or life and often worshipped for doing so, or something that represents this spirit or being’.

1 It may be pluralised, for example, Gods. This paper accepts the existence of God but is open faith and makes no imputation regarding the nature or supremacy of any religion or faith or claims regarding sex, gender, identity or multiplicity of God.

Key Words: veteran, mental health, spiritual health, spiritual wounds and injuries, SW&I, moral injury

Introduction

Jesus, when he had cried again with a loud voice, yielded up the ghost. And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from top to bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent, And the graves were opened, and many bodies of the saints which slept arose, And came out of the graves after his Resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many. Now when the centurion, and they that were with him, watching Jesus, saw the earthquake and those things that were done, they feared greatly, saying, ‘Truly this was the Son of God’. Matthew 27:54.2

In one simple, short and prophetic sentence, ‘Truly this was the Son of God’, an obscure Roman centurion utters the first acknowledgement of the divinity of Christ after his Crucifixion. What lifted this centurion further from obscurity was that he was one of the first recorded cases of a Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I).

A SW&I occurs when a traumatic event or series of events creates a break or change in an individual’s relationship with God or a divine presence. This relationship may be direct or facilitated through a Religious/Spiritual Care Practitioner (RSCP) such as a priest, rabbi or minister. It may be caused by an act of commission or omission by the individual with negative consequences or a perceived failure to act according to their needs or wants on God’s behalf.3-5 A SW&I can significantly impact the mental health and overall wellbeing of individuals who pass through traumatic events or circumstances. It can be particularly prevalent in veterans of the military or armed forces.

While the Crucifixion and subsequent events have resounded across time and space, they had specific implications for one soldier. Longinus was a Roman centurion in the Judea garrison who purportedly pierced Jesus’ side with a spear while on the Cross. A centurion was an important rank in the Roman military organisation. Tactical and practical, these men were usually senior soldiers with many years of hard-won experience and commanded the basic fighting unit of the Roman Army, a century (80–100 Legionaries). As such, it seems unlikely that he would have casually proclaimed the divinity of a non-Roman god. He was also thought to be blind or visually impaired in some way. However, in one of the many miracles that day, he was reputedly cured when the blood and water that poured from the wound in Christ’s side splashed into his eyes.6-8 Longinus may have interacted with Christ and his disciples on three occasions before, during and after the Crucifixion. This is important as it may point to a journey or growth in his faith and beliefs, eventually leading to sainthood.

To understand the importance of this event as a case study of SW&I, this article begins by developing a background profile of Longinus and then places him in the centre of events on the day of the Crucifixion. Using these and subsequent events in his life, the article will describe the specific nature of Longinus’ SW&I and analyse potential implications for modern sufferers of the condition.

Who was Longinus?

The precise historical detail of 1st century Christian figures can be challenging to establish. Often, this is due to issues of basic historiography at the time and subsequent

hagiographical redactions, revisions and, in many cases, fabrications. As such, there are inevitable gaps and contradictions. In the case of Longinus, his history prior to the Crucifixion has yet to be discovered and there are contradictory accounts of his life afterwards. At the same time, these accounts may not necessarily be contradictory but rather sequential.

The principal source regarding events of the Crucifixion are the four canonical Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, although none mention the name Longinus. Of the four Gospels, Luke (23:47), Mark (15:39) Matthew (27:54) mention an unnamed ‘centurion’. John (19:34) refers to a ‘soldier’ and ‘soldiers’. Attribution of the name Longinus to the centurion at the Crucifixion does not appear until the 4th century in the apocryphal Acts of Pilate in the Gospel of Nicodemus.9 Pilate (Roman Governor), writing to Herod (Jewish client king), describes how his wife Percola had ‘heard that Jesus was risen, and had been seen in Galilee, she took with her Longinus the centurion and the 12 soldiers who watched the tomb and went forth, as it were to a great sight, to welcome the person of the Messiah’.10

Two locations are thought to be possibilities for the birthplace of Longinus. Gregory of Nyassa (335–305) claimed in his Letters that it was Sandralis (or Adrales) near Tyana in modern Turkey.11 The second location is the ancient Roman city of Anaxum. The Monks of St. Basil founded a monastery there in the 8th century and named it after Longinus. The city was renamed Lanciano (now in the Chieti province in central Italy), the Italian word for lance.12,13 Lance imagery is an essential part of the overall Longinus tale as his name may have been based on a Latinised Greek word for lance, (λόγχη).14 This also fits with the overall idea of Longinus as a centurion. The principal centurion of a Roman Cohort (6 centuries) was known as the First Spear (Primus Pilus).15

Of course, John’s Gospel does not say centurion but mentions soldier and soldiers. One commentator, Rose Peebles (1911), takes this to indicate that two distinct characters may have been involved in the fateful thrust of the spear. The first was a common soldier, ‘merely a wicked participator in the Crucifixion’, and the other was ‘a convert to belief in Jesus, who at once became a prominent supporter of his faith’.16 The difference between John’s Gospel and the remainder of the canonical Gospels is worth noting. However, the weight of commentary from the Gospels, canonical and apocryphal, tends to favour the presence of a centurion. What is important about Peebles’ assessment is the idea that the centurion Longinus became a ‘convert to belief in Jesus’. It is possible that the centurion whose servant was cured by Jesus in Matthew 8 was not Cornelius as sometimes thought, but Longinus. In addition, a centurion was a senior-ranking soldier within the Roman Army. As such, unlike the common soldiery, a centurion had authority, responsibility, and some (albeit minor) flexibility in the conduct of events.

In contrast, the soldiers at the Crucifixion were thought to have been from Cohors I Sebastenorum, a non-Roman auxiliary unit of Samaritans from Northern Israel/Turkey. Although very much moulded on the model of a Roman legion, their training and equipment were of a lower standard. Despite or because of this, it would not have been unusual for a Roman centurion such as Longinus to be placed in a command position within an auxiliary force, possibly as a retirement position following service in the legions. Given the long-standing issues between the Jews and Samaritans, Cohors I Sebastenorum may have been deliberately placed in this role far from home in an environment where they were less likely to side with the occupied population.17 Some evidence of that can be seen in the epithet given to the Sebasteni cavalry regiment, ‘the hammer of the Jews’.18

Longinus at the Cross

The overall Crucifixion is covered in melancholy detail in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Longinus’ role on the day and during the subsequent Resurrection can be pieced together using the canonical and the apocryphal Gospels.

Scourging

John 19:1-3 says that once Christ had been sentenced to Crucifixion, ‘Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged’.2 Such flogging or scourging was not uncommon before execution as it served two important purposes for the Romans. The first was to break the individual’s will so they were physically weakened and unable to escape. The second was to make a very public point to any witnesses of the power of Rome and the penalty for disobedience. What was uncommon was the mocking and humiliation Christ endured. The Crown of Thorns and a purple robe were signs mocking his kingship, and the verbal and physical abuse were particularly cruel actions. Perhaps, this is what Peebles meant when she described ‘wicked participator(s) in the Crucifixion’.16

Part of the viciousness and severity of Christ’s scourging described in John 19:1, Mark 15:15, and Matthew 27:2 may have been based on the hatred the Samaritan soldiers had for the Jewish people. Even so, Longinus would have been in command of these events. While he may not have participated or even openly condoned the actions, he could have stopped them with a word. Of course, it can be easily argued that as a trained soldier, he was merely following the orders of his superior.

Path to the Cross.

The badly injured and weakened Christ was then led to execution carrying his Cross. Again, this pitiful procession was part of the demonstration of cruelty and power the Roman authorities were trying to project. Longinus would have been in command of this party and may have issued the order to make Simon the Cyrene take up Christ’s Cross when he fell (Matthew 27:32).2 What is not clear is whether this was done as an act of expediency to keep the column moving or an act of kindness.

Crucifixion

Longinus was in command at the Crucifixion. This would have been mostly procedural, and the soldiers would have followed a well-practised routine. Jesus was stripped of his clothing, fixed to the Cross and then hung to die. According to John (19:34-37), a soldier was:

‘sent to break the legs of the condemned men and thus hasten their death. They did not break his legs when they came to Jesus and found that he was already dead. Instead, one of the soldiers pierced Jesus’ side with a spear, bringing a sudden flow of blood and water. The man who saw it has given testimony, which is true. He knows that he tells the truth and testifies so that you also may believe’.2

Breaking the legs of a person undergoing Crucifixion was a common act to hasten death as it would collapse the victim’s lungs. As previously mentioned, none of the Canonical Gospels mentions Longinus doing this, and it seems unlikely that a centurion would have undertaken such a menial task. Christ’s legs were not broken; a spear was thrust into his side under the fifth rib—a deliberate and precise action to deliver a fatal wound. As Christ had only hung on the Cross for a relatively short time, he may not have been dead before the spear thrust. A well-trained centurion would be aware of the effect that such a wound would have had. It would also be most likely caused by a hepatic laceration, which almost certainly would have produced a rapid demise in a scourged, debilitated, dehydrated man.19 The centurion Acts of Pilate in the Gospel of Nicodemus attributes this final act to Longinus

The interesting question is, why did Longinus choose this course of action? Longinus actions of that day were deliberate and followed well-established practices, and he delivered the orders from his superiors. Nevertheless, he had deviated from these orders initially by forcing Simon the Cyrene to help Christ carry his Cross and then piercing him with a spear rather than breaking his legs. Generally, Roman soldiers followed orders to the letter, so this may question whose order she was following. One argument from John 19:31 was that his deviations were merely administrative, as the Crucifixion occurred just before the Sabbath and the bodies had to be taken down. If so, getting the column to the point of execution and breaking the criminal’s legs would have sped up the process, although not as conclusively and quick as a fatal spear wound. That was only used for Christ. Was this a coup de grace or a last act of mercy for a dying man?19 If so, why just Christ and not the criminals?

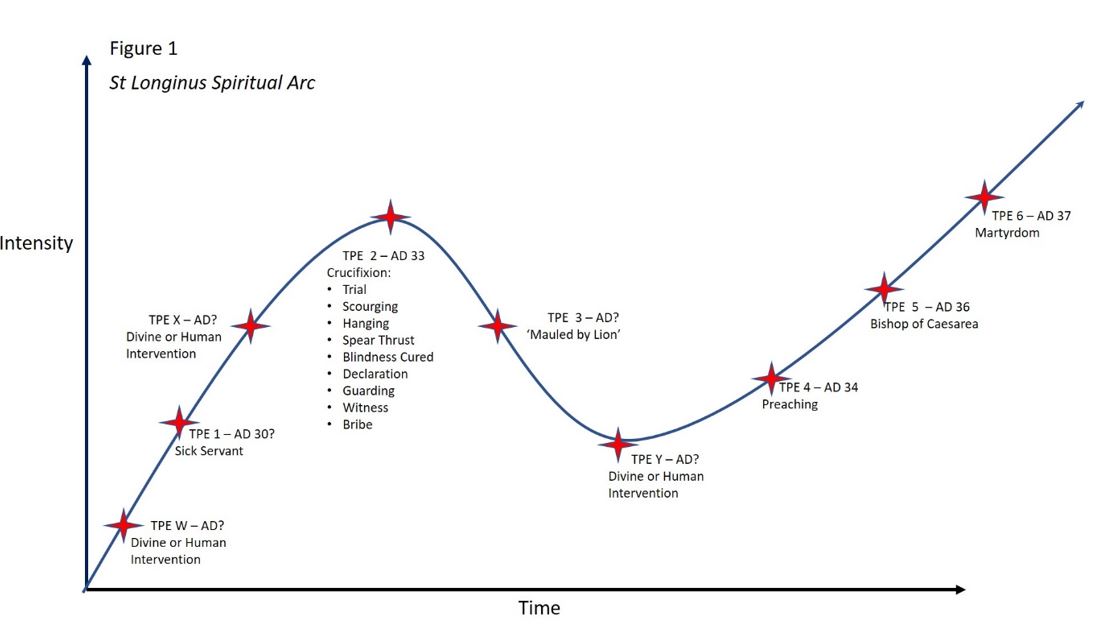

Perhaps Longinus was caught between his orders and his faith. If, as suggested, he was already on a path to belief, it might be argued that Longinus may have known by divine direction that, in some way, his military orders were compatible with a bigger mission. This argument starts with a possible previous relationship with Christ that led him to seek healing for his servant, which may have been the start of an ascent on his Spiritual Arc (see Figure 1).5 It is also possible that he had been made aware of key prophecies in Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53 (see Thin Place Events (TPE) X in Figure 1). Also of note is Zechariah 12:10, ‘I will pour out on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem a spirit of grace and supplication. They will look on me, the one they have pierced’.2 Obliquely, as Christ was the Lamb of God, the commandments in Exodus 12:46, Numbers 9:12 and Psalm 34:20 regarding not breaking the bones of the Passover Lamb may also be relevant.

Guarding the Body

According to Pilate, Longinus and the same 12 soldiers were tasked with guarding Christ’s tomb. Matthew 28:1-6 goes on to report:

‘After the Sabbath, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to look at the tomb at dawn on the first day of the week. There was a violent earthquake, for an angel of the Lord came down from heaven and, going to the tomb, rolled back the stone and sat on it. His appearance was like lightning, and his clothes were white as snow. The guards [presumably including Longinus as the Guard Commander] were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men’.2

The Acts of Pilate in the Gospel of Nicodemus also indicate that Longinus, the soldiers, and Pilate’s wife returned to ‘welcome the person of the Messiah’.10 Matthew 28:12 says:

‘some guards went into the city and reported to the chief priests everything that had happened. When the chief priests had met with the elders and devised a plan, they gave the soldiers a large sum of money, telling them, “You are to say, ‘His disciples came during the night and stole him away while we were asleep.’ If this report gets to the governor, we will satisfy him and keep you out of trouble.” So the soldiers took the money and did as they were instructed. And this story has been widely circulated among the Jews to this very day.’2

This statement implies that Longinus took a bribe to deny the Resurrection. If so, this stands at odds with the previous discussion that he was at least merciful to Christ if he was not an active participant in his journey acting under divine inspiration orders.

After the Crucifixion

Ramsey Michaels noted in 1967 that a ‘wealth of medieval legend celebrates the acts and the martyrdom of this hybrid figure Longinus’.20 Accordingly, several contradictory and overlapping stories of what happened to Longinus after the Crucifixion exist. One version has it that Longinus was condemned to be torn apart by a lion every night, only to have his body restored during the day in preparation for another night’s agony.10 At some point, Longinus was thought to have been converted to Christianity and became an active preacher of the word. As a result, he was persecuted by the Romans and fled from Palestine. In one version of his post-Crucifixion life, he arrived Mantua in 36 CE and was taken care of there at the local hospice until he was martyred on 2 December CE 37.12 A different story has him fleeing from Jerusalem to reside in Caesarea in Cappadocia, where he was appointed bishop and then martyred.21

Rather than being a series of contradictions, these events can be reassembled sequentially to demonstrate Longinus’ Spiritual Arc (see Figure 1). Despite the vagaries of basic historiography and hagiography in this period, Longinus’ spiritual rise, fall, growth and degradation can be mapped against a series of TPE to create a Spiritual Arc.5 These TPEs are the spiritual equivalent of Moral Injury’s (MI) Potential Morally Injurious Events (PMIE).22 The TPE concept is drawn from Celtic mythology/theology and describes ‘thin places’ in the universe or physical places where the visible and the invisible world come into their closest proximity.23 Such spots were considered the border between the spiritual and temporal realms. It is not an unreasonable extension to the concept that significant and horrific events occurring in a particular location and time may also be considered Thin Places. If so, the Crucifixion has to be the best example of this. A PMIE and a TPE may occur at the same time and place. However, each may be interpreted differently by the individual involved.3-5 A potential sequence for Longinus’ Spiritual Arc is described in Figure 1. In the example, there are a number of TPE. TPE W, X, Y and Z represent unknown but possible events. TPE 1–6 represent events described in a number of sources although the dates are approximate.

- TPE W. If Longinus was the centurion who sought Christ’s help for his sick servant (Matthew 8),2 what motivated him to do so? It hardly seems a likely action for a centurion to seek help from a member of a conquered population who was considered a potentially seditious character. It is possible that TPE W was an example of unspecified divine or human intervention or management to guide him in this direction.

- TPE 1. Longinus approaches Christ and asks him to heal his sick servant who ‘lies at home paralysed, suffering terribly’ (Matthew 8:5).2 He does this with an unusual degree of humility and submission, telling Christ that he does not deserve him to come under his roof and that he believes that if Christ says so, the servant will be cured (Matthew 8:10).2 In return, Christ says, ‘Truly I tell you, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith’.2 Again, there is a sense of a missing background encounter there.

- TPE X. It is plausible that after such a momentous encounter, Longinus would be grateful and possibly changed and may have sought out further unspecified divine or human intervention or management to guide him. This may have started a conversion process guided by one of Christ’s followers.

- TPE 2. Longinus led the conduct of the execution from scourging to burial. The critical question that this prompts is: whose orders was he following? Ostensibly, the orders were Pilate’s and Longinus carried these out faithfully and fully. He was led by divine guidance to assist in completing a prophesied and necessary journey. Possibly, this may have been evidenced by the acts of kindness in getting another man to carry Christ’s Cross, and a mercy killing that he initiated that was out of the scope of earthly orders.

- TPE 3. There is an argument that Longinus suffered from some form of visual impairment before the Crucifixion. It cannot have been too severe, as it did not prevent him from serving in the military. In any case, when the blood and water spilled from Christ’s side, they ran down the shaft of the spear and spilled into his eyes, curing them of the ailment.16 This may represent a miracle in recognising his difficult duties and his treatment of Jesus that day.

- TPE Y. In the next period of Longinus’ life, he is condemned to be torn apart by a lion every night, only to have his body restored during the day in preparation for another night’s agony.10 This sounds metaphorically familiar to many veterans suffering from mental illnesses like PTSD.

- TPE Z. At some point, there must have been another unspecified divine or human intervention or management that delivered him from this torment.

- TPE 4. Longinus is described as spending the following years of his life preaching.

- TPE 5. Longinus becomes the Bishop of Caesarea.

- TPE 6. Longinus is martyred.

The Spiritual Wounds and Injuries of St Longinus

As a veteranus (veteran), the circumstances of Longinus point to his experiences as a relevant case study of the causes and presentation of a SW&I.24

Following Longinus’ Spiritual Arc, there appear to be several possible SW&I:

- Change of Faith? Nothing is known about Longinus’ religious beliefs or faith. In general, the Romans worshipped a pantheon of Gods adapted from Greek culture, other cultures they had conquered and or emperors deified after their death. Many Roman soldiers of this period worshipped the God Mithras.25 Something or someone must have motivated Longinus to reach out to Christ for help with his servant. The servant was subsequently cured, and it stands to reason that TPE W represents an unknown moment of change in Longinus’ life. This may have been his conversion or at least the first significant step. This postulation highlights that SW&I following a TPE can also be positive events that strengthen and cause the Spiritual Arc to ascend further.

- Crucifixion. Given what might have been a new or growing faith for Longinus, the Crucifixion would have been tumultuous, on some levels joyous but also profoundly conflicting. Tumultuous as the saviour he was now following was being led to his death under his command. For a person new to the faith, being called by God to undertake the actions of that day would have almost been incomprehensible. Even if he was just a witness, being in such a situation may have caused him to question the omnibenevolence of God, leading him to ask, ‘Why God, did you do this to me?’ It would also have been a joyous occasion as he was healed of his vision issues and witnessed the risen Lord. It conflicted on every level because the joy of healing set against the day’s awful events. With the day’s horror, there may have been the knowledge that he was playing an important part in some part of a bigger mission. At the same time, he may have been experiencing great shame in knowing he took a bribe to deny that Christ had risen. The incredible mixture of this tumult, joy and conflict may have created a significant SW&I that affected his mental health and overall general wellbeing.

- Mauling. It is little wonder then that in the next period of Longinus’ life, he is condemned to be torn apart by a lion every night.10 These lions, doubt, shame, and guilt are the same that afflict veterans whose experiences with trauma have caused a break or change in their relationship with God. Doubt about whether he made the right decision to follow Christ, then act as he did and what, if any, was God’s plan in this engineered horror. Shame in acting a way they feel may have angered or dishonoured him in God’s eyes, such as taking a bribe to deny what happened. Also, guilt at following orders and divine direction led to the death of Christ. This may have manifested as anger, depression, anxiety or other typical mental health conditions.

- Healing. TPE Y represents another unknown moment of change in Longinus’ life. Someone or something pulls Longinus out of a degrading Spiritual Arc. It sets him on a path of preaching, culminating in his appointment as Bishop of Caesarea. There is no indication of who or what this may have been. Some apocryphal sources indicate he was in contact with the broader Christian community and perhaps even the disciples. Perhaps they facilitated and supported his healing. It could have also been a comrade. Acts 10:1 says that ‘there was a certain man in Caesarea called Cornelius, a centurion of the band called the Italian band’.2 This was likely Cohors II Italica Civium Romanorum, part of the Roman Garrison (Stagnaro, 2017). Healing of a SW&I will involve a range of different practitioners, both spiritual and temporal. Still, the importance of ‘mates’ cannot be underestimated. Since Cornelius and Longinus were senior centurions, they may have moved in the same military environment, knowing and supporting each other in their parallel faith journeys.

Implications for contemporary veterans

Despite the almost 2000 years that have passed since Longinus’ fateful act, the circumstances of this 1st century Roman centurion still have significant relevance as a case study for contemporary veterans suffering from SW&I:

- Professional soldier. Longinus was a professional soldier. As a centurion, he had over 20 years of service across several campaigns. He would have been experienced, well-trained and professional. Although such preconditioning undoubtedly would have helped, it would not have made him invulnerable to being spiritually wounded and injured. Many individuals have or will become veterans following the long-running coalition wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Australian experiences in Bougainville, East Timor and other locations. Despite the length of their service, they are likely to have a significant burden of damage, some spiritual, that will need to be addressed for many years to come. Like Longinus, their SW&I may be immediate, while others may only occur once triggered by a TPE many years later.

- Complex operations in enemy territory. The Roman Army in Judea was an occupying force. In many ways, the force was a coalition of elements from across the Empire comprising Roman Legions and Samaritan troops, such as Cohors I Sebastenorum. This would have been ‘yet another deployment’ for the Roman legionaries. In contrast, the Samaritan troops that Longinus commanded had a particular enmity towards the Jews. Australian soldiers faced similar complexities in Afghanistan when working alongside coalition and Afghan National Army soldiers against local and international Al-Qaeda fighters.

- Difficult decisions. There appears to be some evidence that Longinus had encountered Jesus or perhaps his followers and supporters before the Crucifixion. He may have also received some instruction regarding this new and emerging faith. Nevertheless, he had been given a task by his superiors to complete. In the Roman Army, orders were very much orders, and there was no leeway for disobedience, regardless of personal beliefs and feelings. Contemporary veterans may have also been in similar circumstances where their orders were following the Laws of Armed Conflict and specific Rules of Engagement but still felt Regardless, they had to be carried out, and this may have left a lasting burden on the soldiers that would be carried well into their veteran years.

- While Longinus could have hardly released Christ, he chose some actions that were skimming the edge of disobedience to help him. In particular, getting another man to carry Christ’s Cross and a possible mercy killing was out of the scope of earthly orders. On the other hand, Longinus took a bribe to deny the Resurrection. While bribery in the ancient world was common, taking a bribe from the Jewish temple elders would have been against Roman law and a denial or diminishment of his possible emerging faith. Such compromises, even ones with honourable intentions, create conflict. Some veterans live with the implications of such compromises for many years. Examples may include events where an appropriate order and militarily necessary strike against a legitimate target create unintended ‘collateral damage’ to innocent parties. In a personal faith sense, compromising orders, even for what may be a good reason, is still breaking orders. Many veterans may suffer lasting mental health and wellbeing issues unless some form of forgiveness for their choices can be found.

- Mauling. The mauling of Longinus is a good metaphor to describe how some veterans will suffer. Each night, he would be mauled by lions and, in the morning, would have recovered sufficiently to be mauled again that night. This reflects a cycle of suffering and treatment that may seem endless for contemporary veterans. In a medical or psychological sense, this may mean waves of depression or anxiety coloured by substance abuse and anger that are reduced and possibly eventually cured through pharmacological and counselling interventions. A similar paradigm applies to those suffering from SW&I, albeit this will involve spiritual counselling and support led by principally religious and spiritual care practitioners with support from others.

Conclusion

There were many wounds suffered on the day of the Crucifixion. One of the mob that came to arrest Christ lost an ear to Peter’s sword. Mary lost a much-loved son, and the disciples lost a teacher, a father and a friend. Christ suffered terrible wounds to his flesh—not least of these being the fatal thrust from Longinus’ spear. The centurion who commanded the Crucifixion also suffered a series of SW&I, which would follow him in one way or another for the rest of his life.

Although other historical and Biblical figures before Longinus demonstrated some aspects of SW&I, Saint Longinus is worthy of specific consideration on many levels. To start with, with seven simple words, ‘Truly this was the Son of God’ he was the first person to publicly declare the divinity of Christ after his Crucifixion. In many respects, it is a sensational and almost outrageous statement from a man who was very much part of the occupying Roman military establishment. It is a statement that may have been drawn from a growing faith that may have been n and shaped before that day. While the interventions at TPEs W, X and Y are postulations, logically, there must have been some act or words that changed the behaviour of this highly experienced soldier. It is important to remember that SW&I can also represent a positive change in an individual’s relationship with God.

At the same time, the events on the day of the Crucifixion would have tested anyone’s faith. The momentous moments after Christ’s death have to be set against his sheer joy of restoring his eyesight.6-8 Yet, despite this, Longinus took a bribe to deny the event (Matthew 28:12).2 These tumultuous, joyous and deeply conflicting events led to a SW&I that plunged Longinus into nightly terrors where the lions of doubt, shame and guilt mauled him every night. This is an experience that many modern veterans suffering from a SW&I would understand.

Corresponding Author: Murray James Davies, murray.davies62@gmail.com

Authors: M J Davies1

Author Affiliations:

1 PhD Candidate UNSW Canberra