Abstract

Tinnitus is among the top three most frequently accepted service-related conditions for Australian veterans. Veterans have described the effects of tinnitus as causing physical, emotional and social problems. In addition, many veterans with tinnitus, especially those with troublesome tinnitus, have other health conditions, such as hearing loss, insomnia, anxiety and depression.

Research suggests tinnitus develops due to maladaptive neural changes in auditory and non-auditory pathways. This is thought to be due to actual or potential physical or psychological trauma. Hence, treatments focusing on physical and psychological factors, including emotional, attentional, behavioural and social aspects, obtain the best outcomes in reducing tinnitus-related distress. The most promising therapy to address these factors is cognitive behavioural therapy, particularly in a multidisciplinary setting, for which robust evidence exists.

Keywords: tinnitus, cognitive behavioural therapy, hearing loss

Introduction

Tinnitus is complex, multifactorial and not fully understood. It is the perception of sound that has no external source, commonly described as ringing, buzzing, hissing, clicking or humming perceived in one or both ears and as coming from within or outside the head. Research suggests that it most often develops as a result of maladaptive neural changes in auditory pathways and in attentional, memory, cognitive and emotional areas of the brain. This usually happens after an actual or potential physical or psychological injury, much the same way that cognitive-affective processes play a key role in the experience and maintenance of chronic pain.

Military personnel are often exposed to hazardous occupational noise, including noise from gunfire and machinery during service are at high risk of tinnitus. In addition, they may be exposed to somatosensory system disturbances and emotional stress during service. 2 Traumatic brain injury (especially blast-induced), concussion, hearing loss and post-traumatic stress disorder experienced by military personnel can lead to or exacerbate tinnitus. Veterans are vulnerable to ‘acoustic shock’ an involuntary trauma response to a sudden, brief and unexpected loud sound, for example, blasts and weapon fire. This can lead to tinnitus, startle reactions and hyperacusis (an increased sensitivity to sound in which the person may find sounds painful or distressing). This sensitivity can lead to anger, anxiety and depression, significantly impacting quality of life. Unfortunately, it is not well understood, diagnosed or treated.

In the United States, tinnitus is the most prevalent service-related disability of veterans registered with the Veterans Benefits Administration. In 2020, tinnitus was among the top three conditions accepted as service related for Australian veterans, with 39 500 having an accepted tinnitus condition. Of these, almost 9000 served in East Timor, Solomon Islands, Afghanistan and Iraq (contemporary veterans), and 11 500 were Vietnam Veterans.

Veterans with tinnitus may be reluctant to talk about their tinnitus or its full impact on their lives, even with their family and friends, and ‘soldier on’ without seeking help. There may be several active military personnel and veterans in Australia who have tinnitus but have not shared that information with family members or sought treatment.

This review describes the impact tinnitus can have on veterans’ lives and emphasises the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), to reduce the perceived severity of tinnitus.

The impact of tinnitus on veterans’ lives

Veterans and active military personnel have described the effects of tinnitus as causing physical, emotional and social problems, which have a detrimental effect on concentration, work performance, communication and interactions with other people. Many veterans report that they cannot relax or sleep well, which stops them from enjoying a full social life. For active service personnel, the effects of tinnitus may influence their ability to carry out assigned tasks, especially in combat situations.

Not all veterans with tinnitus are troubled by it. Many can adapt to the noise over time. Some report it as being of a moderate problem, but still requiring intervention. For others, their emotional wellbeing is substantially affected by their tinnitus. Many of these veterans have other health conditions in addition to their tinnitus, such as hearing loss, sleeping problems, traumatic brain injury, substance misuse disorders and mental health issues, including anxiety and depression. Some veterans with troublesome tinnitus may also experience social phobias and adjustment disorders. Others report feeling angry and frustrated, overwhelmed, exhausted, hopeless or even suicidal. Some veterans with tinnitus have multiple comorbid mental health conditions and complex needs that require careful planning of their treatment.

Tinnitus is often a chronic condition for which no medical or pharmacological treatment is currently available. A multidisciplinary approach that addresses cognitive, behavioural, attentional, emotional and social aspects can help to reduce the perceived severity of tinnitus and improve veterans’ quality of life.

Early referral of veterans to a psychologist or audiologist

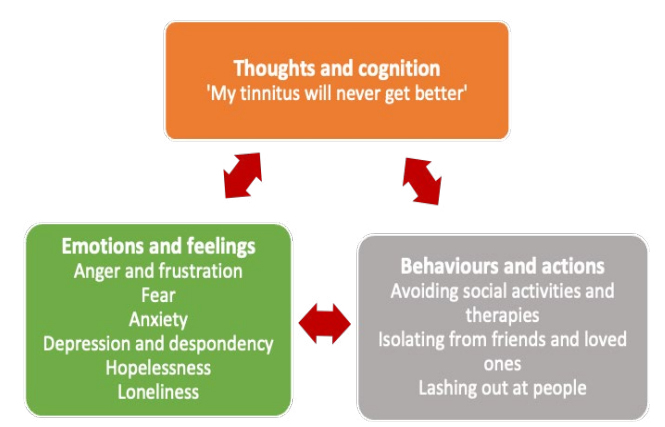

The most promising therapy to address cognitive, behavioural and emotional factors associated with tinnitus is CBT, for which there is robust evidence. CBT, delivered by trained psychologists or audiologists, primarily focuses on identifying negative or unwanted thoughts about tinnitus that results in distress, and challenging, modifying and replacing those thoughts and emotions with more helpful and realist beliefs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The negative and irrational thoughts, emotions and behaviours about tinnitus that are challenged and restructured by the psychologist during CBT

An audiologist can help patients understand how neurological pathways work to process potentially threatening sounds and why tinnitus can be triggered and propagated. In addition, acknowledging the trauma of what may have caused the tinnitus can help prepare the foundation for CBT.

CBT aims to reduce tinnitus-related distress and improve quality of life. It may not reduce the noise of the tinnitus or eliminate its occurrence. CBT is strongly recommended, especially if tinnitus is troublesome and distressing.

CBT for tinnitus includes learning relaxation techniques and sleep hygiene. Internet or smartphone-based tinnitus treatments that include CBT have been shown to be helpful. For veterans with chronic pain and tinnitus, psychological treatments, such as CBT that addresses psychosomatic symptoms, negative coping attitudes and emotional tension, can reduce both tinnitus and pain-related distress.

CBT can also help address depression, anxiety and poor sleep, and is strongly recommended as first-line therapy before any prescription of an antidepressant, anti-anxiety or hypnotic medicine.

Box 1: Resources for health professions to treat veterans with tinnitus

- Comprehensive tinnitus information for the public as well as information and training for clinicians

at: www.tinnitusaustralia.org.au - An audiologist at: www.audiology.asn.au

- A psychologist (Australian Psychological Society) at: www.psychology.org.au/Find-a-Psychologist

- A psychiatrist (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists) at: www.yourhealthinmind.org/find-a-psychiatrist

- Other health services, including social workers and occupational therapists (Healthdirect) at: www.healthdirect.gov.au/australian-health-services

- The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders at: www.ranzcp.org/practice-education/guidelines-and-resources-for-practice/mooddisorders-cpg-and-associated-resources

- Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling

- For mental health and wellbeing support for DVA clients, Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling is available 24/7 by phoning 1800 011 046

- For assessing and treating veterans with anxiety, PTSD, depression, insomnia, alcohol and substance misuse, problematic anger or complicated grief, go to: www.openarms.gov.au/healthprofessionals/assessment-and-treatment

- To help your veteran patient access a suite of self-help SMART (Self-Management And Resilience Training model) tools designed specifically for them to enhance their stress management skills and build resilience by addressing physical responses, thoughts, emotions and behaviours, go to: www.openarms.gov.au/get-support/self-help-tools#!/home

- To help your veteran patient access a suite of short videos (1–20 minutes) to learn to relax and gain control using controlled breathing, muscle relaxation and meditative strategies, go to: www.openarms.gov.au/get-support/self-help-tools/show-all-tools

Referring veterans to an audiologist for assessment, review or treatment, including devices

Noise-induced hearing loss, often associated with tinnitus, can exacerbate the distress experienced by veterans with troublesome tinnitus. Sensorineural hearing loss is the second most common condition accepted as service related among Australian Research in the United States suggests CBT for tinnitus is not commonly discussed as a treatment option for veterans with tinnitus. Analysis of Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) health claims data indicates that only 8% of White and Gold Card holders with tinnitus have made a claim for a psychologist’s visit.

Through non-liability health care, DVA funds evidence-based mental health treatment provided by mental health professionals for mental health conditions for veterans without needing the condition to be accepted as related to service. For further information, go to: www.dva.gov.au/health-andtreatment/injury-or-health-treatments/mentalhealth-care/free-mental-health-care-veterans

Vietnam and contemporary veterans. Thirteen per cent of the known 39 500 Australian veterans with tinnitus have claimed a hearing device. Some veterans with tinnitus may not be aware they have hearing loss. Trouble communicating and the resultant frustration and distress might have more to do with undiagnosed hearing loss than with their tinnitus.

Untreated hearing loss is associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia, social isolation,26-28 depression and irritability. Treating hearing loss can lessen the intrusiveness of tinnitus. The additional benefits of treating hearing loss include improving concentration, communication, cognition and quality of life.

Offer to refer veterans who report hearing difficulties or have tinnitus that is troublesome, and who have not seen an audiologist recently to an audiologist for an assessment or review, or to discuss devices to help with tinnitus. An audiologist can conduct impedance audiometry and tympanometry to assess hearing deficits and middle ear and eardrum function, provide tinnitus rehabilitation and counselling, and fit hearing aids and assistive listening devices as needed.

Audiology Australia can help find an audiologist at: https://audiology.asn.au/Home The list can be filtered to find an audiologist who specialises in treating people with tinnitus.

Box 2: DVA-funded hearing services and tinnitus treatments for eligible Veteran Card holders

- Audiology consultations and investigations to assess hearing and tinnitus can help determine whether tinnitus and hearing loss are service related.

- Hearing devices and support through the Australian Department of Health Hearing Services Program on 1800 500 726 or at: www.hearingservices.gov.au.

- Assistive listening devices through the Rehabilitation Appliances Program (RAP), including:

- induction loops (a cable that picks up and transmits sound to a hearing aid allowing better hearing in a designated induction loop area)

- headsets for watching television

- microphones and frequency modulation (FM) listening systems (a handheld microphone that transmits sound directly to the hearing aid)

- doorbells and smoke alarms with lights

- streamers that transmit sound from a mobile phone, tablet or television to a hearing aid.

- Cochlear implants and treatment through the Hearing Services Program. Phone 1800 500 726.

- Tinnitus treatment for eligible veterans with severe tinnitus that cannot be managed through the Hearing Services and RAP programs. Only an audiologist or ENT specialist can refer a patient for the DVA-funded tinnitus treatment. Treatment may include:

- a clinical assessment and treatment by a specialist audiologist

- specialised counselling by a specialist audiologist, for example, tinnitus retraining therapy and use of sound enrichment devices

- hearing aids with tinnitus settings and devices to assist with sleeping.

For further information about eligibility, programs, services or hearing devices, contact DVA on 1800550 457 or go to: www.dva.gov.au/providers/health-programs-and-services-our-clients/hearing-serviceinformation-providers.

Under the Repatriation Transport Scheme, DVA funds transport assistance for eligible Veteran Card holders to travel to approved treatment locations. If your patient requires assistance with transport to approved tinnitus appointments, go to: https:// www.dva.gov.au/about-us/overview/overview-dvabenefits-and-services

Referral to an ear, nose and throat specialist

Consider referral to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist for further investigations and treatment if the tinnitus is:

- pulsatile or unilateral

- rapidly progressive

- associated with sudden, asymmetric or fluctuating hearing loss

- associated with a feeling of fullness or pressure in one or both ears

- associated with vertigo or balance problems.

To find an ENT specialist, go to Healthdirect, at: www.healthdirect.gov.au/australian-health-services

Education, support and self-care can empower veterans

Many veterans in a United Kingdom study expressed a need for a better understanding of tinnitus and access to support groups. Research indicates a possible way to reduce severe symptoms can be found for many people when they are able to understand their tinnitus better. In particular, how the brain evaluates and filters sounds subconsciously via auditory and non-auditory pathways, and how the somatosensory system and negative thoughts and beliefs can influence tinnitus severity.

Information and support can be empowering; encourage veterans with tinnitus to access Tinnitus Australia at: www.tinnitusaustralia.org.au and to read through DVA’s The Veterans’ guide to better hearing to gain an understanding of tinnitus and hearing loss, available at: www.dva.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/p04129-guide-to-better-hearing.pdf

Talk to veterans with tinnitus

Explain to veterans that:

- tinnitus is a symptom rather than a disease, and many strategies can help reduce its perceived severity

- while medical investigations may be needed initially to rule out possible causes, tinnitus rarely indicates a serious illness

- no single treatment works for everyone. A coordinated multidisciplinary approach that involves a range of strategies, including CBT and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, selfcare, education, mindfulness and relaxation, communication and auditory therapies, and devices such as hearing aids and assistive listening devices, as well as sound therapy, can be helpful. These therapies focus on helping the person to adapt and better manage their emotional reaction to their tinnitus

- tinnitus can be a bit like an ‘emotional barometer’; emotional stress, anxiety, poor general health, pain, lack of sleep or exposure to loud noises can heighten the noise along with anxiety and distress. Likewise, doing enjoyable things each day can help make the noise seem less noticeable and lessen anxiety and distress.

There are no proven medicines to improve tinnitus

Although numerous medicines, herbal extracts, dietary supplements and vitamins have been tried in the treatment of tinnitus (for example, antidepressants, anxiolytics, antiepileptics, betahistine, Ginkgo biloba, melatonin and zinc), there is little to no evidence that these therapies are of benefit to people with tinnitus. In addition, these medicines and supplements could also have adverse effects and interact with other medicines.

Some veterans may think that the medicines they take for tinnitus, such as anxiolytics or antidepressants, help their tinnitus. Explain to veterans the importance of stopping ineffective therapies and emphasise the benefits of seeing a psychologist to help them adapt to their tinnitus and reduce their distress. While some medicines may not be able to be changed or stopped, it may be appropriate to taper or cease many.

For information on how to:

- taper or cease antidepressants, go to: www.veteransmates.net.au/topic-49-therapeutic-brief

- manage benzodiazepine dependence, go to: www.nps.org.au/news/managing-benzodiazepinedependence-in-primary-care.

To help veterans better understand the risks associated with taking sedative-hypnotic medicines, direct them to: www.criugm.qc.ca/fichier/pdf/BENZOeng.pdf, or for further resources about medicines and falls or memory loss, go to: www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/patients-and-public.

Medicines rarely cause tinnitus

There are many anecdotal reports of medicines causing tinnitus, but there is acceptable evidence for a small number, and in these cases, tinnitus as a side effect occurs only rarely. The risk of ototoxic effects from medicine use is higher with older age, long-term use, renal or liver impairment and when ototoxic medicines are combined. Most ototoxic effects are temporary and dose-dependent. In most cases, normal doses do not cause tinnitus.

Medicines associated with ototoxic effects include:

- Antimalarial medicines, including quinine-based agents; tinnitus can occur with prolonged daily doses greater than 200–300 mg, but is usually reversible.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, with doses higher than 4 grams per day. Tinnitus is almost always reversible within a few days of discontinuation of the aspirin. Tinnitus occurs in less than 0.1% of patients with other NSAID use.

- Loop diuretics, including furosemide, produce a dose-related, usually reversible ototoxicity, primarily affecting patients with renal impairment

- Tinnitus can occur with furosemide when a total daily intravenous dose is greater than 240 mg,44 or oral administration of 160–800 mg per day in patients with renal impairment

- Antibiotics, including aminoglycosides (gentamicin and streptomycin), glycopeptides (vancomycin) and macrolides (erythromycin and azithromycin)

- Chemotherapies, including methotrexate, cisplatin, carboplatin and vincristine. Effects may be temporary or permanent.

Conclusion

Tinnitus is a common service-related disability associated with psychological distress and poorer functioning and health among veterans and military personnel. Better recognition, assessment and management of tinnitus in both military personnel and veterans may reduce suffering and improve quality of life.

While there is currently no pharmacological or medical treatment for tinnitus, several effective management strategies can help veterans to improve the quality of their everyday lives. CBT seems to be the most promising therapy; however, many other things can help, including audiologist referral, educating patients about their condition, talking and sound therapies, relaxation and mindfulnessbased therapies, and group support. These are best implemented using a coordinated multidisciplinary framework.