Introduction

The 2000 ADF Health Status Report identified that over the five years from 1994 to 1998 suicides were the third leading cause of death (behind natural causes and motor vehicle accidents) and accounted for

17% of deaths for permanent ADF members. 1 Mental illness, a major risk factor of suicide, is a leading cause of working days lost from hospitalisation of ADF personnel and constitute a significant component of ADF medical invalidity retirements, reports to DEFCARE and claims accepted by Department of Veterans Affairs. Suicide, suicide-related behaviours and mental illness appear to be significant problems affecting the efficiency of the ADF.

Aim

This paper examines ADF data on suicide. Suicide related behaviours and mental illness for the period 1985 to 2000. Recommendations towards the development of prevention strategies and interventions are also briefly discussed.

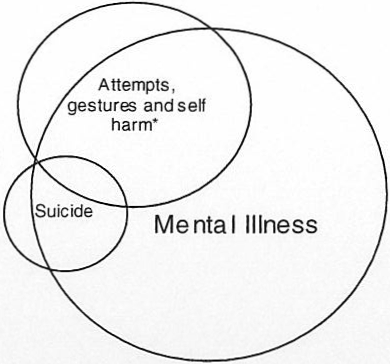

Figure 1: Theoretical Relationship between Suicide, Attempts/Gestures and Self Harm and Mental Illness. (While not technically correct, these illnesses are considered together here to enable meaningful comparison)

Background

Risk factors for suicide include a vast array of mental health, family, relationship, societal and situational factors. However, as the majority of suicides and suicide-related behaviours occur within the context of mental illness, these issues cannot be discussed in isolation. The relationship between suicide, attempts and gestures, self-harming behaviour and mental illness should be considered as separate conditions that overlap, not an all-inclusive continuum (Figure 1).

Mental Illness

Australia

A survey of the Australian community in 1997 estimated that 18% of Australian adults in the community suffer from a mental disorder.2 More than 50% of people with mental disorders are affected long term; however, only 40% seek help or have their problem diagnosed. Silburn et al reported that the prevalence of mental disorders was around 27% for persons aged 18-24 years. 22% for 25-34-year-olds, 20% for 35-44-year-olds and 18% for 45-54-year-olds .

Mental problems and disorders are responsible for a large number of hospitalisations within the community, account for much disability, incur high health costs and impose a heavy burden of suffering including stigmatisation.

In 1996, in the Australian community, mental disorders were responsible for 13.3% of the total disease burden and for about 30% of the non-fatal burden.4 Depression was the leading cause of non-fatal disease burden and mental disorders accounted for 10.2% of the total number of patient days in public hospitals.4 The Australian rate for admission to hospital for mental illness was 10.6 per 1000 persons per year.

Australian Defence Force

In the absence of complete mental health information, the ADF has to be considered as a subset of the wider Australian community. Determining the relative differences between the ADF and the wider community is difficult and the relative proportions of mental health and mental illness remain unknown due to confounding factors.

In 1996, the admission rates of Service personnel for mental illness were 18.0 per 1000 personnel per year for RAN, 6.6 per 1000 personnel per year for ARA and 7.2 per 1000 personnel per year for RAAF. Overall, the ADF admission rate for mental illness was 10.3 per 1000 personnel per year. The ADF is more likely to admit personnel to hospital for minor mental illness and ‘transient situational disturbances’. This is in keeping with its young isolated population, the inherent lack of personal support available within this population, and the lower threshold requirements for hospital admissions.

Antidepressant and antipsychotic drug usage in the ADF in 1998 was 421 person-years.! Assuming an average usage of three to six months per person treated, the number of personnel treated in 1998 was 20.3 per 1000 personnel and for 1999 was 23.4 per 1000 personnel (485 person-years). It cannot be determined the extent to which hospital admissions for mental illness overlap with drug usage, although it is expected that a substantial proportion of personnel with mental illness are treated as outpatients.

Substance abuse is a significant mental health risk factor for ADF members. In 2000, a tri-Service working party was established to target the incidence of alcohol abuse in the ADF. The ADF also has significant numbers of smokers a reduction of which is likely to result in significant positive health effects.

General factors that contribute to poor mental health include the breakdown of relationships, separation from loved ones, stress5, changes in well being, changes in health status, financial difficulties and the loss of someone close. ADF members are not immune to these issues, and military life also places additional stresses on its personnel that may contribute to the incidence of mental illness,6 including:

- sudden and prolonged isolation from home and families;

- restriction of choice and freedom;

- imposed discipline;

- numerous interstate moves;

- performance anxiety relating to high expectations; and

- succeed or fail ethos.

Suicide Attempts/ Gestures and Self Harm

While it is not technically correct to include these behaviours in the same category, the delineation has not been made clear in many reports. Self-harm (eg. intentionally cutting self) is distinctly different from suicide attempts and gestures, however, to provide a meaningful comparison, these behaviours are discussed together in this paper.

Australia

Suicide and self-harm accounted for 20,131 hospital admissions during 1997-1998, more than 53,000 patient days in total which is 0.4% of all patient days for public hospitals and 4% of the patient days for mental disorders and diseases in public hospitals.7 This equates to an overall rate of 10.6 per 10 000 personnel.

Australian Defence Force

In general, suicide attempts and gestures are poorly reported to Defence Health Service Branch. This issue is being addressed through changes to the ‘Notification of Casualty’ requirements for the ADF. In 1998, data on suicide attempts and gestures was collected and is provided here for consideration. For1998, there were 16 incidents of suicide attempts and gestures and 30 incidents of self-harm. This equates to a rate of 8.3 per 10,000 personnel per year, slightly less than the Australian rate.

Suicide

Mental disorders are one of the most important risk factors of suicide. Some studies indicate that of those who complete suicide 9 in every 10 have some form of mental disorder at the time of death. Alcohol abuse is present in 25 per cent of cases. Major depression, substance abuse, schizophrenia, personality disorders, medical conditions and deliberate self-harm all carry higher risks. Other risk factors include a history of previous suicide attempts, a history of sexual or physical abuse, and exposure to the suicidal behaviour of others. These risks do not establish causation, but point to the importance of interacting influences, both socially and medically. It must be remembered that the majority of individuals with a psychiatric disorder do not suicide.

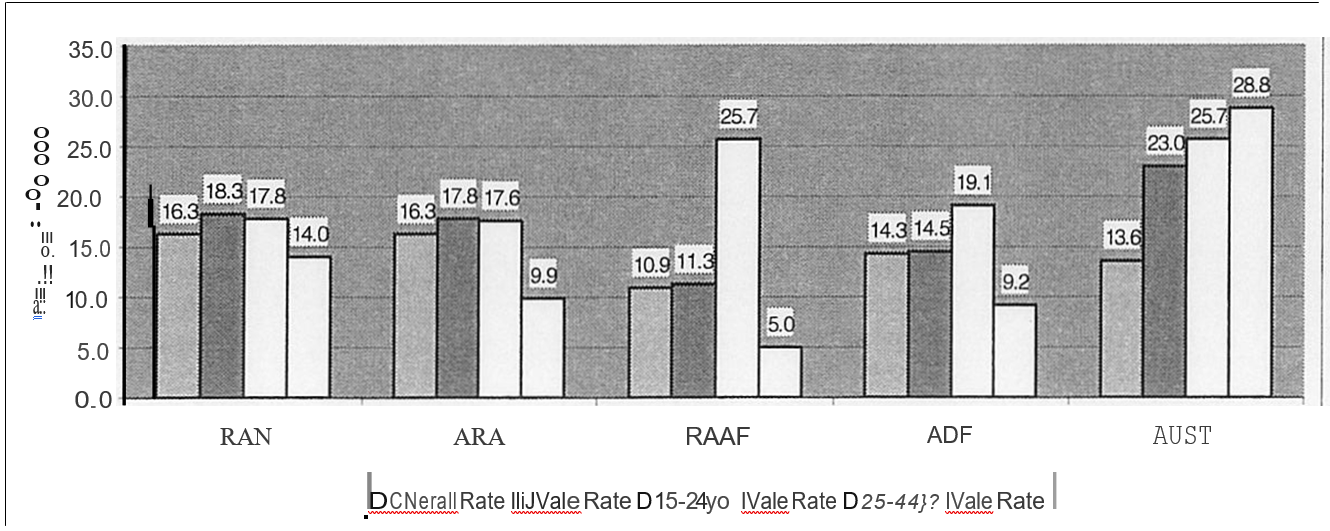

Figure 2: Suicide Rates in the ADF by Service compared to the Australian Population Rate (1985-2000)

Australia

Approximately one-third of persons who die by suicide were receiving medical treatment immediately before the episode. Suicide and self-harm accounted for 20,131 hospital admissions during 1997-1998, more than 53,000 patient days in total.7 The high-risk groups for suicide in the Australian community include:

- Aged between 25 and 44 (50% of all Australian suicides were in this age group in 1998).

- Male (80% of successful suicides in 1998 were male).

- Mental disorders (account for 60-90% of suicides. Individuals with depression, schizophrenia or personality disorders are at most risk).

Australian Defence Force

The ADF expects lower rates of suicide due to:

- Enlistment procedures designed to detect personnel with psychiatric disorders, medical problems and drug/alcohol misuse.

- Higher intelligence levels.

- Lack of attractiveness of the military to other high-risk groups.

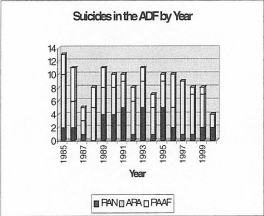

There have been a total of 142 suicides since 1985, 38 RAN members, 75 ARA members and 33 RAAF members. Figure 3 is the number of suicides in the ADF, split into the three Services by year. There have been a total of seven female suicides since 1985: 1 RAN member, 2 ARA members and 4 RAAF members.

The rate of suicide in the ADF from 1985 to 2000 was 14.3 per 100,000 per year. The average annual rate of suicide for the RAN and ARA was 16.3 per 100,000 and RAAF was 10.9 per 100,000.

Figure 3: Number of Suicides in the ADF by Year (1985-2000)

Male Suicide Rates. In Figure 2, The suicide rate per 100,000 has been stratified into two age groups for the single Services, the ADF as a whole and the comparative rate for the Australian population. Chi-squared testing was performed on this data, controlling for differences in the size of the populations, and the results indicated:

- For the 15-24-year-old group, the Australian population rate and all ADF rates are not significantly different at the 0.05 level.

- For the 25-44-year-old age group, only the overall ADF Male rate is significantly less than the Australian rate (also 0.05). For the single Services, the numbers are too small to result in statistical significance.

It can be seen when analysed in this manner, that suicide in the ADF is indeed a significant problem, particularly in the 15-24 year old age group, where the ADF’s rate closely approximates the rate for the Australian community.

Given that the ADF screens its personnel prior to entry it could be interpreted as somewhat disappointing that the suicide rate for the younger age group in the ADF is not significantly less than the rate for the Australian population at large. However, there is a complex array of risk factors that have been associated with suicide, and this area requires further investigation.

Non commissioned ranks are more likely to commit suicide (12.9 per 100,000 per year) than officers (7.4 per 100,000 per year). This difference in rates is not statistically significant.

The methods used for ADF suicides are illustrated in Table 1. A comparison with the Australian population is provided. Hanging, firearms and carbon monoxide poisoning are the most common methods used by ADF personnel to suicide.

| Method | ADF* | Australian Popn* (15-24 year Hangingolds) |

|---|---|---|

| Hanging | 31% | 38.5% |

| Gunshot | 26% | 16.8% |

| Carbon Monoxide | 26% | 14.9% |

| Drug Overdose | 8% | 9.3% |

| Fall | 3% | 6.2% |

| Other | 7% | 13% |

Prevention

There are three levels of prevention:

- Primary prevention – targets the Defence community as a whole by increasing awareness and education levels and promoting mental health.

- Secondary Prevention targets personnel who are identified as being at risk, to encourage them to seek treatment early to prevent worsening of their condition beyond reasonable recovery levels.

- Tertiary prevention – targets personnel with known mental illness and/or suicidal tendencies and encourages an appropriate multifaceted approach to management of their condition to maximise opportunity for recovery and retention within the Service.

All stages of prevention are appropriate within the ADF; however, primary prevention is most likely to have the greatest impact and thus provide for the greatest opportunity for manpower conservation. It has been argued that suicide prevention should target more broadly based risk and protective factors, rather than focusing specifically on suicide. The aim of prevention programs should be to reduce not only suicide but also other social, behavioural and health problems. The costs of primary level prevention programs can then be applied to achieving multiple health and mental health outcomes.

The effectiveness of many promotion and prevention strategies is yet to be demonstrated, although interventions to improve people’s mental health literacy, optimistic outlook, problem-solving skills, resilience to life stress and social support appear to be helpful.5.9 In recent years the United States Air Force has adopted a community approach to suicide prevention and preliminary findings have indicated a significant reduction in the suicide rate.10 Within the ADF, the Defence Force Psychology Organisation is trialling a suicide awareness and prevention training package within Army Training Command Units. The efficacy of the trial is currently being evaluated and the package is being considered for tri-Service application.

Intervention

Interventions measures for suicide are often debated as they can only hope to reduce the suicide rate, not eliminate its and include:

- Access to counselling from an appropriately qualified person.

- Education of colleagues, commanders and professional personnel as to the warning signs of suicide.

- Encouragement for people at risk or identified to be at risk to self-refer for help.

- Management guidelines for professionals to detect, assess and treat at-risk members.

Therapy for depression appears to be associated with a reduction in suicide rate, as does restricting access to methods commonly used to commit suicide, restricting opportunities for imitation, and the introduction of education programs. At a secondary level, access to appropriate psychiatric care and crisis intervention is recommended.

Conclusion

Suicide prevention is an important part of preventive health. The ADF is currently experiencing rates of suicide comparable to the Australian population in the younger age groups when theoretically this rate should be lower. The ADF is also experiencing significant rates of mental illness resulting in significant morbidity, the true magnitude of which, can only be estimated. It is unclear as to whether life in the military carries unique risks of mental illness and suicide. The situation warrants a tri-Service program to prevent, detect and treat mental illness across the ADF.

Recommendations

- Surveillance. Improve the surveillance of mental health, self-harming behaviour, suicidal gestures and suicide attempts in the ADF to incorporate:

- data on the incidence of these issues;

- working days lost as a result of these issues;

- data on the utilisation of multiple areas in the treatment and support of these individuals; and

- data on outcomes.

- Investigation. Establish a tri-Service, multidisciplinary project team to further investigate mental health, self-harming behaviour and suicide issues in the ADF and develop an ADF Mental Health Strategy. Investigation should include prevention and intervention measures and development of ADF protocols on the assessment and management of suicide and related behaviours.

- Adopt best practice as an interim measure. As an interim measure, until the results of such an investigation are known and a mental health strategic plan is developed, current knowledge can be utilised to assist in prevention and intervention programs. Current knowledge favourably reports the adoption of community-based suicide prevention programs, such as the one already being trialled and evaluated by the Defence Force Psychology Organisation,12 with the view to adopting the program Defence wide in the future.