Ruben M. Jacubovich MD MoccH, Occupational Health Specialist Physician, Occupational Health Section Consult Service Clinic, IAF

Maj. Michal Zilberberg MoccH, Head of the Occupational Health Section IAF

Col. Liav Goldstein, MD MHA, Surgeon General IAF

Col. jacob Haviv MD, MPH, Chief Medical Officer IDF Central Command

Col. Nehemia Yoffe, MD MHA, formerly Surgeon General IAF

Col. Yaron Bar-Dayan, MD MHA, Chief Medical Officer IDF Home Front Command

ABSTRACT

An enormous amount of literature has been published on aviation physiology, most of it dealing exclusively with aircrew. Only rarely are the occupational problems of ground personnel addressed. An occupational health consult service referral clinic was established in the Israeli Air Force in 1993.

We present a retrospective analysis of periodic and fitness-for-work examinations of 1472 medical encounters of ground personnel between the years 2000-2002 who were examined in this clinic.

An upward trend is seen concerning the total number of visits in the clinic in the last decade. The four most common causes of fitness-for-work examinations were: musculoskeletal (29%), respiratory (17%), neuropsychologic (13.9%) and skin (12%) problems.

The four most common causes of periodical examinations visits were: crane operators (38.7%), noise surveillance (34.4%), solvent exposure follow up (13%) and hydrazine exposure follow up (6.4%).

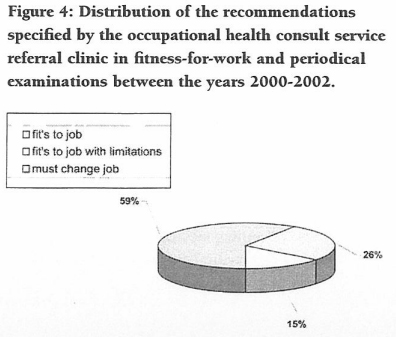

In 15% of all the examinations, health impairment was found leading for complete disability to the required job, and 26% of examinations resulted in partial work restriction recommendations.

The activity described in the occupational health consult service clinic reflects the special occupational hazards in military aviation ground personnel occupations.

KEYWORDS

Morbidity, occupational health clinic, military aviation, ground personnel.

INTRODUCTION

Occupational medicine has its roots in ancient history. It began in the era of Hippocrates, and became a specialty, due to the efforts of Paracelsus, Georgius Agricola and Bemardino Ramazzini (1,2,3).

In Ramazzini’s famous book, “De Morbis Artificum”, written in the 18th century, many diseases caused by exposures at work were described, including the occupational diseases of painters, potters and glassmakers (3).

Aviation medicine, on the other hand, has only recently been established. An enormous amount of literature has been published on aviation physiology, most of it dealing exclusively with aircrew. Only rarely are the occupational medical problems of ground personnel addressed, despite the fact that in the aviation industry, pilots and other aircrew comprise only 10-15% of the total aviation industry workforce, whereas ground personnel make up the remaining 85-90% (4,5,6).

Furthermore, ground personnel are exposed to a variety of occupational hazards (physical, chemical, biological, psychosocial and ergonomics) which demand special consideration (7).

Since 1993, an occupational health consult service referral clinic has been active in the Israeli Air-Force. Due to increasing demand, it has been operated on a regular basis by an occupational health specialist, for the past 3 years.

The aim of this article is to present the results of a 3 year-work in the occupational health clinic of the Israeli Air-Force, the number of visits, the distribution of the causes of visits and the results of visits in term of job restrictions recommendations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Collection:

The Israeli Air Force occupational health consult service referral clinic was opened in 1993. During the first years and up to the year 1999, it was partially operated by occupational physicians belonging to the military reserve forces. In 1999, an occupational health specialist physician began working in the clinic the clinic one day per week.

Up to 1999 all periodic checkups were conducted in the Air Force base primary care clinics by primary care physicians. Since 1999 these physicians are being qualified to make medical monitoring for some of the occupational hazards required by law, after short, but intensive, medical training, and are working under the supervision of the occupational health section in the IAF headquarters.

The primary care physicians are directed to refer any abnormal result to the occupational central clinic for further follow up. Workers exposed to certain occupational hazards, such as hydrazine, ionizing radiation, and crane operators are under medical surveillance only in the occupational health consult service referral clinic.

Fitness-for-work examinations are done by the occupational specialist only after referral from the Air Force base primary care clinics.

Data source:

The medical record file of each employee includes questionnaires concerning medical and occupational history, the results of medical examinations, laboratory tests, medical specialist evaluations, diagnoses, recommendations, description of treatment and prescriptions.

Study design:

The data concerning the visits in the occupational health consult service referral clinic between years

2000-2002 was compiled from the medical record files, by the occupational health specialist physician of the Israeli Air Force (IAF).

The number of visits to the central occupational health clinic per year was counted, and data concerning the cause of visit and the result of each visit collected and analysed.

Categorisation of visits objectives:

The visits objectives were categorised into two main groups: periodic examinations and fitness-for work examinations.

Periodic examinations subclassification:

Periodic examinations were subclassified according to the occupational hazards to which aviation ground personnel were exposed (solvents, noise, dust, hard metals, pesticides, hydrazine, radiation, chrome and crane operators).

Fitness-for-work examinations subclassification:

Fitness-for-work examinations were subclassified according to the body systems (musculoskeletal, respiratory, neuropsychologic, dermatologic, ophthalmologic, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hematologic, endocrine, others).

Categorisation of medical outcome of the medical encounters:

The results of the visits were divided into 3 groups in term of work fitness:

- Waiver to continue the same occupation without restrictions.

- Waiver to continue the same occupation with partial restrictions.

- Recommendation to change occupation.

RESULTS

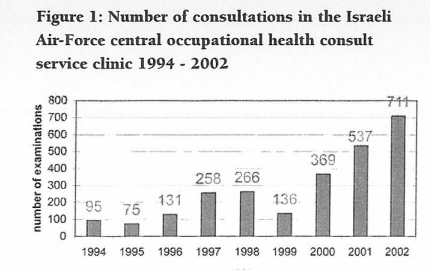

The number of consultations completed in the occupational health clinic has grown in the last decade (Figure 1). The number of consultations has been almost duplicated between the years 2000, and

2002, and has been raised from 369 encounters in the year 2000 to 537 in the year 2001 and 700 in the year 2002.

The 815 periodic examinations and 656 fitness-for-work examinations which were done between the years 2000-2002, comprised 55.4% and 44.6% of the total number of visits respectively.

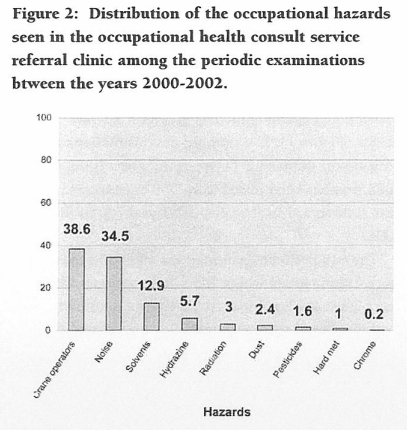

The distribution of the 815 occupational periodic examinations according to the different occupational hazards is shown in Figure 2. The four most common categories were: crane operators (38.6%), noise surveillance (34.5%), solvent exposure (12.9%), and hydrazine (5.7%).

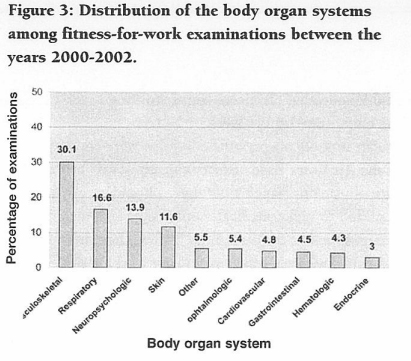

The most common complaints in fitness-for-work examinations were musculoskeletal (30.1%), respiratory (16.6%), neuropsychologic (13.9%) and skin problems (11.6%) as shown in Figure 3.

Health impairment leading to work change recommendation was found in 15% of the examinations (Figure 4), whereas most of the workers were found able to continue with their job, with minor restrictions or without any limitation.

Figure 1: Number of consultations in the Israeli Air-Force central occupational health consult service clinic 1994- 2002

Figure 2: Distribution of the occupational hazards seen in the occupational health consult service referral clinic among the periodic examinations between the years 2000-2002.

Figure 3: Distribution of the body organ systems among fitness-for-work examinations between the years 2000-2002.

Figure 4: Distribution of the recommendations specified by the occupational health consult service referral clinic in fitness-for-work and periodical examinations between the years 2000-2002.

DISCUSSION

An upward trend is seen concerning the total number of visits in the Israeli Air Force occupational health consult service referral clinic in the last decade.

Periodic examinations:

The most common subgroups of periodic examinations were crane operators, noise solvents and hydrazine surveillance. This finding accords with Air Force ground personnel being commonly exposed to these hazards.

The most common occupational disease, both in and out of the aviation industry, is noise-induced hearing loss. Over 50% of airport maintenance workers who were exposed constantly to aircraft noise were found to have hearing loss (8).

The high number of visits of crane operators can be explained by the requirement for a special license from an occupational specialist for this job.

Hydrazine surveillance reflects the special aviation environment in military operations. Servicing modem combat aircraft involves replacing, emptying and filling the hydrazine units carried on board of aircrafts. Hydrazine is being used as a fuel for emergency power units which supply power to the plane when the engine fails (7).

The increase of environmental monitoring to other occupational hazards, such as benzene, kerosene, strontium chromate, flour and more, predicts an upsurge of additional periodic examinations in the near future.

Fitness-for-work examinations:

The four most common groups of health problems seen as the cause of visits at the occupational health consult service referral clinic in fitness-for-work examinations are musculoskeletal, respiratory, neuropsychologic and skin problems.

The military aviation environment has special features compared with civilian counterparts (7). Aviation military ground personnel are exposed to great strain, due to the special military aviation environment. Lifting and carrying heavy objects may lead eventually to musculoskeletal complaints (7).

Low back pain is known as the most common musculoskeletal complain, both in the general population and in the workforce with over 50% of adults reporting an attack sometime in the past (8,9,10).

Additionally, it is the most common cause of restricted activity for those under 45 years old (11), the same age group of the ground personnel employed in the Israeli Air Force. In agreement with our results, research on military populations indicates that musculoskeletal-related disorders represent the most prevalent source of outpatient visits, lost work time, and disability (12).

The most common medical problem encountered by the occupational physician at Ben Gurion airport during fitness-for-work assessments for aviation ground personnel was low back pain (20.6%) (13) and the overall musculoskeletal problems reached 33.5% (7), which is consistent with our results.

Fueling of military aircrafts, repairing and cleaning of aircraft parts, the talc used on flotation gears (life vests), the use of polyurethane foam, ammunitions maintenance chemicals such as solvents, degreasing agents and paints, emission from aircraft engines, hydrazine treatment in emergency power units, a requirement to be ready for an instantaneous shift from peacetime to combat operations, put ground personnel at risk for respiratory, skin, and neuropsychologic injuries (7).

Skin diseases account for 30-50% of all reported occupational diseases in the United States (14,15) and are considered a major occupational disease (16). Skin problems are also a major issue in the occupational health clinic as shown.

Occupational asthma is one of the most frequent work-related diseases (17), and the most common occupational lung problem (18).

The exact prevalence of occupational asthma is unknown (19) and is estimated between 2-6% of all cases of asthma (17, 20), with wide prevalence variations between different chemicals exposures (21).

The high percentage of fitness-f or-work examinations due to respiratory disability (16.6%) can be associated with the vast variety of respiratory hazards and with recruitment of soldiers having pre existing asthma. Israeli soldiers who were recruited to the Israeli military service with preexisting asthma, were at a higher risk for respiratory complaints (22). Also, a significant proportion of adult-onset asthmatics may have occupational causation, while an even larger proportion have the aggravation of underlying asthma (22,23).

Neuropsychologic complaints were found in 13.9% of fitness-for-work examinations, 70% of them were “headache” complaint. Headache is most prevalent among persons younger than 55 years (24). Both physical and mental work were strongly associated with frequent headache (24). Analysis of pain complaints and psychological distress among soldiers in specialty military medical clinics in Israel showed that headache was the second most common pain complain with a positive linear relationship with psychological distress (25). Headache is one of the most common complaints due to occupational exposure to organic solvents (26).

The military Air Force environment, including mental and physical stress, psychological distress, exposure to chemical, especially organic solvents, and the young age of Air Force ground personnel, explain the high incidence of headache complaint in the occupational health clinic.

The activity described in the occupational health consult service referral clinic reflects the special occupational hazards in military aviation ground personnel occupations.