Introduction

Previous articles in this series described the development of a cycle from prehistory to the end of the Tudor period, whereby increasing maritime trade necessitated larger and more efficient ships to transport merchandise and better weapons to defend or attack them, facilitating further trading opportunities.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 However, it was not until the 18th century that Western medicine had developed sufficiently for its role as an enabler of this cycle to be recognised, thereby making possible—among other things—the European settlement of Australia.8

While the technical developments in ships, weapons and medicine often developed independently in multiple regions worldwide, they remained closely linked throughout Western history. This article continues this series by filling the gap regarding the developments in naval warfare, ships and medicine during the Stuart period from 1603 to 1714.

Stuart naval warfare

Besides their dynastic and religious origins, the Stuart wars with Spain (1625–1630, 1654–1660 and 1701–1713), Holland (1652–1654, 1665–1667 and 1672–1674), and France (1627–1629, 1689–1697, and 1702–1713) were also fought for the domination of American, Indian and Far Eastern trade. It was only during the last of these wars that England (Great Britain from 1707) maintained an army in Europe; instead, it fought almost exclusively naval wars, by which its trade provided the funding to fight and support its allies on the continent while eventually bankrupting their opponents. However, these operations were frequently ruined by failures to maintain seamen’s health.9,10

Although James I’s reign (1603–1625) generally only required about 30 warships for English Channel anti-piracy duties during the summer months, lack of money and endemic corruption rendered them more-or-less ineffective. As a result, Charles I’s wars with Spain and France comprised a succession of debacles caused by non-seaworthy ships, bad victualling and disease outbreaks, in particular dysentery, typhus and scurvy. These occurred at levels that had not been seen since the aftermath of the 1588 Spanish Armada, such that a 1625 expedition to Cadiz led to the first English sick lists and the first (albeit extemporised) hospital transports.11

Meanwhile, despite Dutch and Portuguese resistance, the English East India Company (EEIC) established its first ‘factories’ in modern Indonesia in 1601 and in India from 1612. Its huge profits came to fund its ‘Indiamen’ (see below) such that, unlike the King’s ships, these were well-found, manned by adequately-paid crews, and had more and somewhat better-quality victuals and medical supplies. Although this led to the EEIC rather than the navy becoming the repository of England’s 17th-century maritime medical expertise, it will be seen how the developments in ventilation, sanitation, personal hygiene, victualling and water quality necessary to reliably keep even their own crews alive lagged until after the 1740s.

During the English Civil Wars from 1641 to 1651, the navy’s role was to prevent foreign interference. On coming under Parliament’s control in 1644, its status changed from a personal possession of the monarch to an instrument of state, which gave it access to better funding. Besides expanding its size, Parliament marginally improved service conditions (including its medical arrangements), making them somewhat less disparate relative to the EEIC’s. These developments helped the English interdict Dutch trade with its colonies during the First Dutch War. In addition, the capture of Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655 provided a base for England to expand its West Indies trade (typically sugar and enslaved people) over the next 150 years at the expense of their Spanish, French and other rivals.12 These wars also saw battle tactics evolve from melee fighting, during which ships would empty one broadside into an opponent, turn to fire the other and then withdraw to reload, into forming ‘lines-of-battle’ whereby ships would form a bow-to-stern line to continuously batter their opponents while protecting each other from being raked from forward or aft.13

The navy’s new tactics and increasing size quickly led to overwhelming numbers of what would now be referred to as Battle Casualties (BCas), which necessitated the first of five Sick and Hurt Commissions from 1653. High BCas and Disease and Non-Battle Injury (DNBI) rates in the West Indies (the former typically comprising malaria and yellow fever in addition to the usual dysentery, typhus and scurvy), led to the first dedicated English hospital ships from 1655.14

Following the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the RN further expanded during the Second and Third Dutch Wars, both of which required their own Sick and Hurt Commissions. Although the 1688 Glorious Revolution brought England into a succession of continental conflicts, its maritime trade wars continued, which paid for its navy (over 250 ships by 1713) and funded its allies and the army in Europe while eventually bankrupting its opponents. With the end of these wars, the last Sick and Hurt Commission became a permanent Board, tortuously leading to the Admiralty Medical Department (now the RN Medical Director General (Naval)) in 1832.

Figure 1. First Dutch War, Battle of Kentish Knock, 28 September 1652.15 Note the absence of a ‘line-of-battle’ formation, which tended to create relatively few BCas.

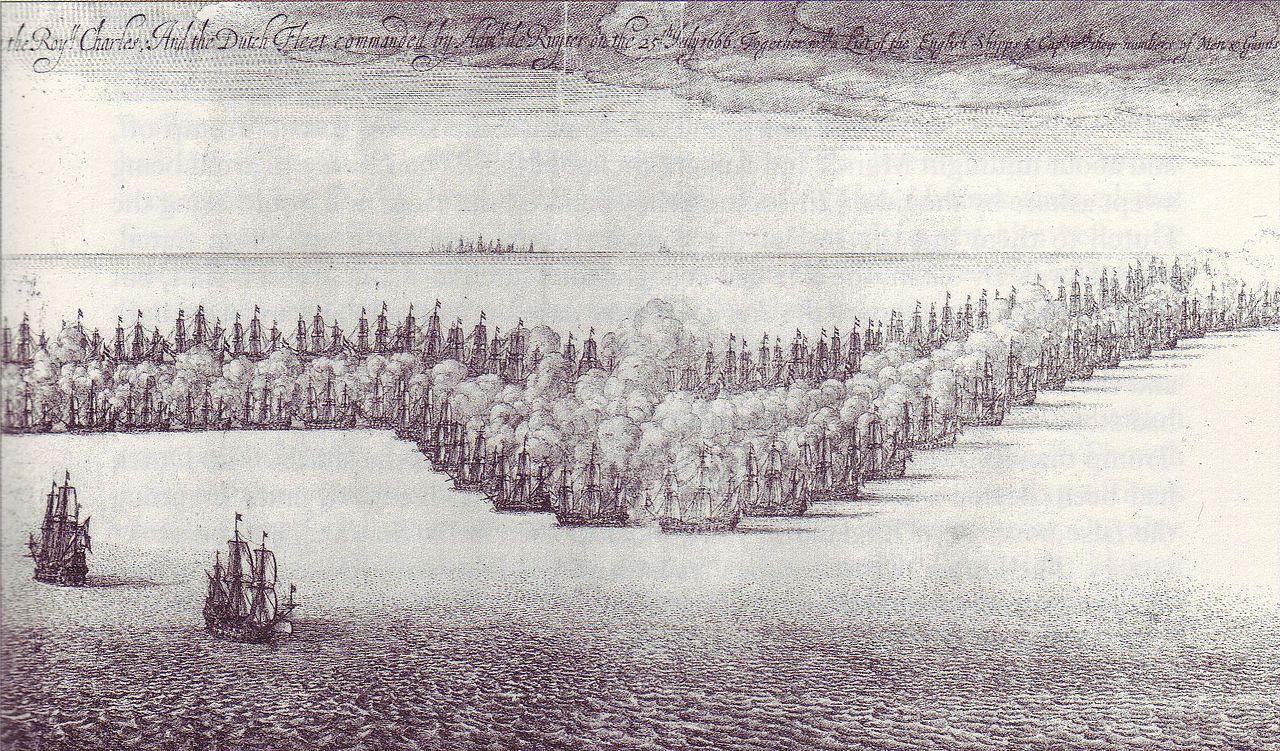

Figure 2. Second Dutch War, St James’ Day Battle, 25 July 1666.16 Although rather stylised, note the ‘line-of-battle’ formations, which produced more BCas.

Stuart ships

A previous article explained how, by 1600, Portugal, Spain, England, Holland and France had developed ships that could voyage more-or-less anywhere worldwide in search of trade, colonies and/or plunder.17 These ships enabled the Spanish colonisation of central and south America and the Philippines, and Portuguese colonies in Brazil, Africa, India and the East Indies. The following century saw Portugal lose most of the East Indies to the Dutch, and the English and French taking over many of Spain’s Caribbean colonies while establishing new colonies in northeast America.

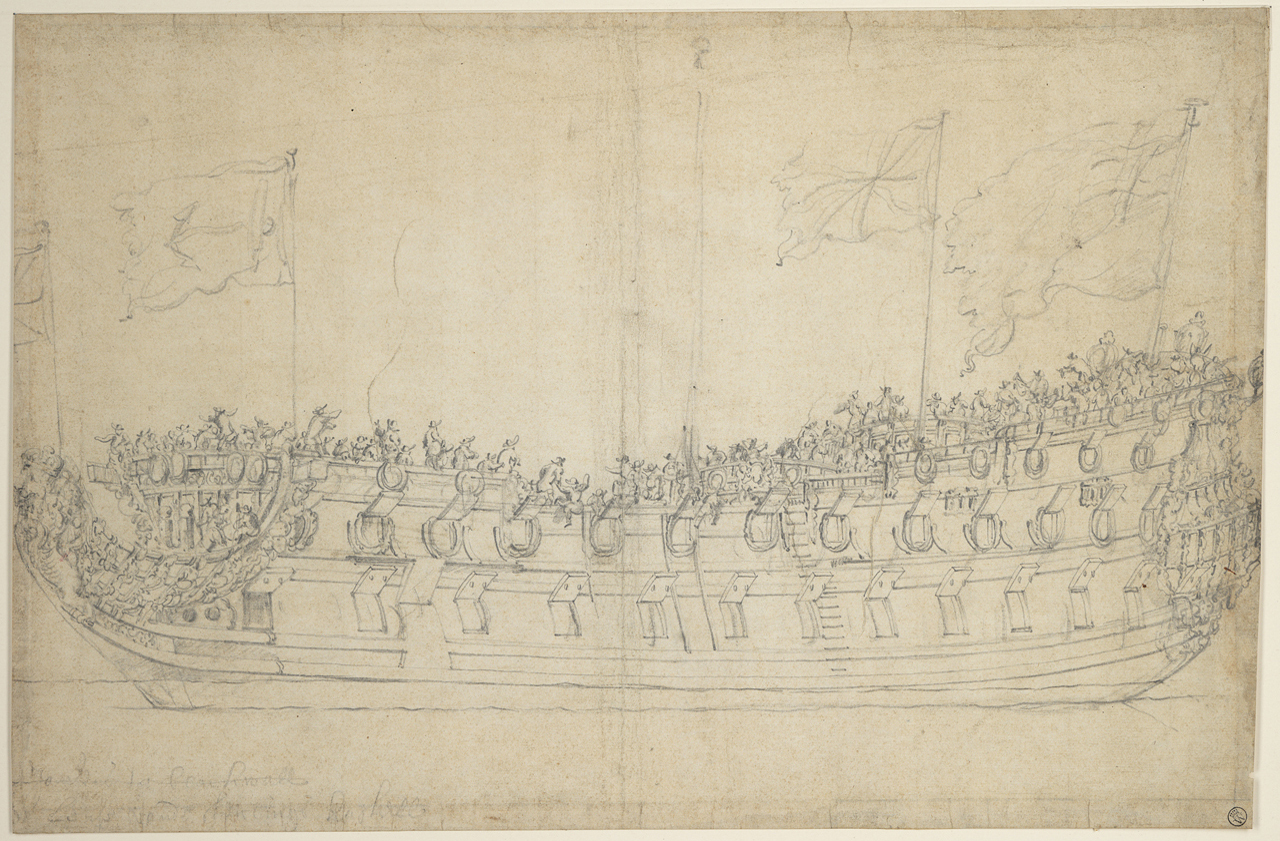

Previous articles also explained how the same ships were used for warlike and peacetime purposes until the invention of watertight gun ports after 1500 began their differentiation into bespoke warships and merchantmen. By the 1620s, warships were carrying large-calibre cannons on up to three gun decks; their holds were permanently subdivided into dedicated store rooms for food, water and ammunition in lieu of cargo, and their crews included large numbers of seaman-gunners to fight as well as sail their ship. It also found that small soldier contingents remained useful for guard duties, boarding actions and amphibious raids. Following their formal introduction in 1664, the first English ‘sea soldiers’ became a permanent force in 1755, titled the Royal Marines from 1802. Besides coming exclusively under Admiralty control, marines were distinguished from Army soldiers in that they performed seamen tasks additional to their military duties, except they could not be ordered aloft.18

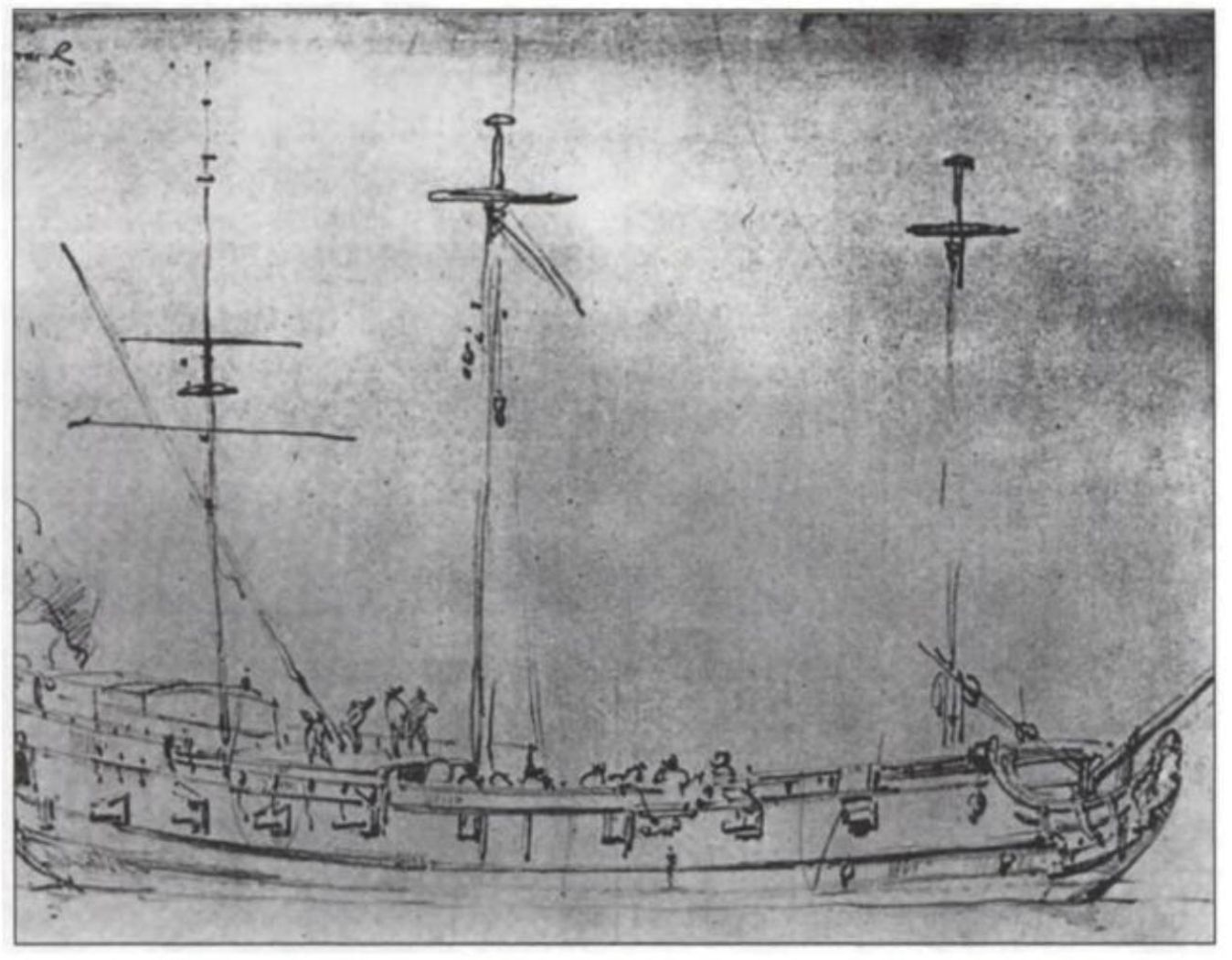

By the second half of the 17th century, warships themselves had differentiated into those with two or three gun decks that could fight in a battle line (hence ‘ships-of-the-line’ or ‘line-of-battle’ ships), and those with only one gun deck known as ‘frigates’, which were fast enough to act as fleet scouts, and large enough to operate over long distances to attack the enemy and defend their merchant shipping independently. 19,20,21 Meanwhile, merchantmen generally kept their crew sizes small to minimise costs and their holds clear to maximise cargo capacity while carrying small-calibre cannons on their weather decks for self-defence.

The ‘Indiaman’ was the exception, developed by the EEIC following its foundation in 1600. These were big ships with warship-like gunports and large crews armed with smaller-calibre cannon, but also spacious merchantman-like holds.22,23 Although they were not naval ships, Indiamen became crucial to English maritime power over the next two centuries. Firstly, their size and armament allowed them to conduct high-value transoceanic trade with friendly indigenous populations (and to plunder those less friendly) and to attack or defend against their commercial rivals. Secondly, like the triangular transatlantic trade described in a previous article (including the notorious ‘middle passage’ slave component), the taxes on their cargoes paid for the navy that eventually dominated the seas around Europe, which was used to isolate their competitors from their colonies and markets.24,25 Finally, the Indiamen’s large crews substantially increased the pool of otherwise scarce trained seamen that the navy could employ during wartime.26

Figure 3. 70-gun ship-of-the-line HMS Stirling Castle, 1679.27 Note the two full-gun decks.

Figure 4. Frigate HMS Drake, c.1707.28 Note her small size and single-gun deck.

Figure 4. Frigate HMS Drake, c.1707.28 Note her small size and single-gun deck.

Figure 5. Dutch merchant ship, c.1665.29 Note her small size, upper deck cannons… and the single below-deck gun (forward, below the foremast shroud chains).

Figure 6. English East Indiaman fighting off a smaller Spanish privateer, 1682.30 Note her large size and two gun decks (although her cannon would have been smaller than those on a warship).

Figure 6. English East Indiaman fighting off a smaller Spanish privateer, 1682.30 Note her large size and two gun decks (although her cannon would have been smaller than those on a warship).

Stuart naval medicine

Patient care afloat

A previous article described how the institution of Henry VIII’s ‘Navy Royal’ in 1509 created the need for the first English naval sea surgeons.31 These were recruited by the London Barber-Surgeon’s Company on a short-term casual basis for the summer anti-piracy patrols, with wartime augmentation as required (the latter often by ‘impressment’ or compulsion). Nevertheless, despite its increased size and operational scope during the Stuart period, naval surgeons had no permanent employment until 1729.32

While the larger ships often had surgeon’s mates, it was not until 1652 that all seagoing surgeons had at least one to assist with the workload and provide redundancy irrespective of their ship’s size.33 Apart from the ‘loblolly boys’ to help feed the sick,34 their messmates provided seagoing nursing care, while hospital ships only carried additional sailors for nursing duties from 1703. These proto-medical assistants were not formally required aboard warships until 1833, and they had no formal training or career structure until 1884.35,36

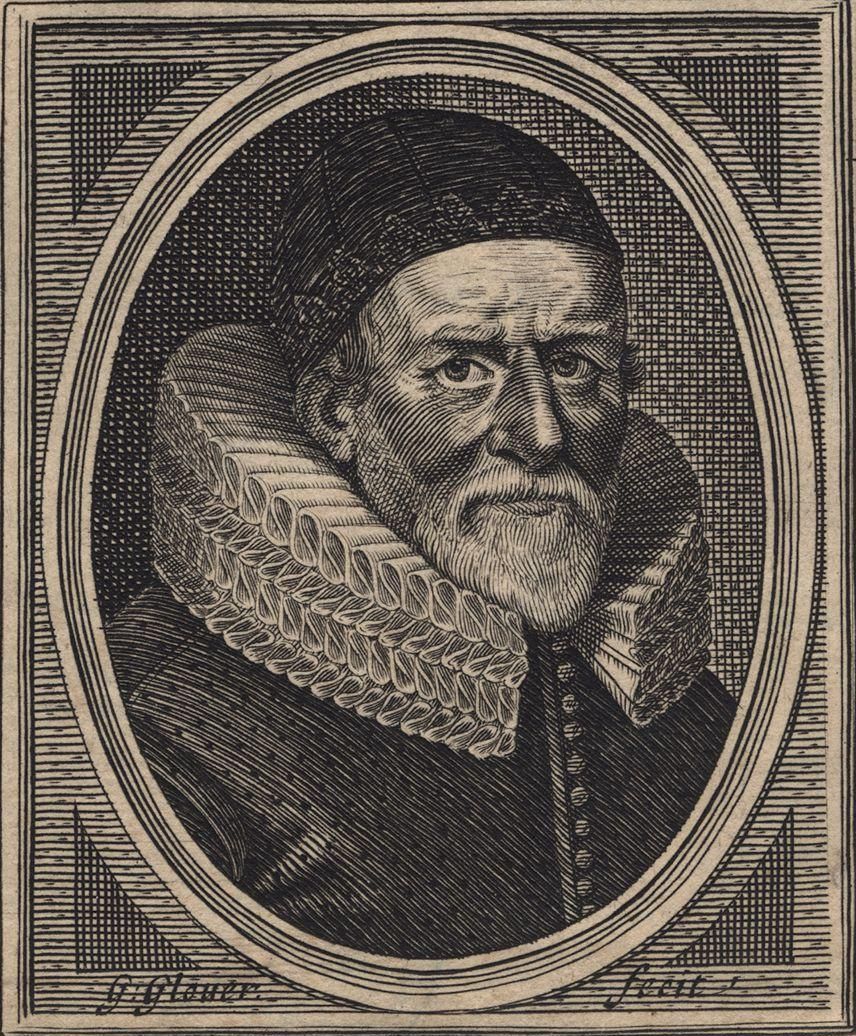

Despite never having served at sea, John Woodall (c1570–1643) had a central maritime medical role during the early Stuart period. After going to war in France in 1589–90, he spent some time in Germany before his admission to the London Barber-Surgeon’s Company in 1599, becoming an examiner in 1626, Warden in 1627 and Master in 1633.37

Figure 7. John Woodall, 1639.38

A previous article described how, although some Tudor commanders provided financial assistance via an ‘imprest’ or loan, their surgeons had to provide their own medical equipment and stores.39 Woodall’s maritime medical role began in 1606 when the London Barber-Surgeons Company was granted the right to examine all sea surgeons and to fine those with unsatisfactory medical chests. It delegated this responsibility to Woodall, by which he became the EEIC Surgeon General from 1612 to 1635. This entailed recruiting and examining candidate surgeons, selling them their medical chests and buying back their unexpended stores. Although his duties did not compare to the Dutch East India Company’s more extensive medical organisation, they nonetheless resulted in the EEIC rather than the navy providing the first long-term careers for English sea surgeons. Woodall was probably also involved in the barber-surgeons supporting a 1626 petition by navy surgeons for a ‘free gift’ additional to their ‘imprest’ in response to the medical failures during Charles I’s war with Spain. Woodall thereafter extended his EEIC duties to the navy, even without being appointed (or even paid) to do so.40

Despite the split in the English medical profession between surgeons and physicians, Woodall advocated training sea surgeons in internal medicine. To this end, he required his EEIC surgeons to produce the first maritime medical journals, which he used to write The Surgion’s Mate in 1617 and The Viaticum, being the Pathway to the Surgion’s Chest in 1628. These were combined into The Surgeon’s Mate or Military and Domestique Surgery in 1639, which Woodall intended explicitly for naval use. It was not until 1704 that navy surgeons likewise had to submit medical journals with the details of each case, and even then, these were only used to validate their per capita remuneration rather than disseminating any lessons learned.41

Woodall’s 1617 text was intended for inexperienced surgeons and novice surgeons’ mates dealing with medical and surgical conditions at sea and in the tropics. The first section describes the chest contents and their indications for use. The second comprises short notes on acute surgical problems, including wounds, gunshot wounds, burns, abscesses and fractures, and the third likewise regarding medical conditions, including dysentery, enteritis and scurvy. The fourth is a treatise on applying chemistry to disease, concluding with a glossary of alchemist terms.42

Although he described the chests’ surgical instruments and their use in some detail, Woodall rarely advised incision. He also gave precise instructions on using dental forceps and considered no surgeon’s mate competent unless he was proficient at drawing teeth.43 His account of Medicines Physicall and Chirurgicall includes 270 animal, vegetable or mineral items, which were more numerous and somewhat less alchemic than those in the Mary Rose medicine chest 70 years earlier.44Woodall also assigned a specific place for each item in his chests, rather like the system used by the Australian Royal Flying Doctor Service 300 years later.45

Figure 8. Plan, John Woodall’s surgeon’s chest, 161746

Woodall’s 1616 appointment as surgeon to St Bartholomew’s Hospital would have brought him into contact with William Harvey (1578–1657), the first physician to accurately describe the circulatory system in lieu of the errors made by Galen of Pergamon 1400 years previously. Even so, Woodall’s medical advice remained based on the physicians’ reliance on increasingly complex humoural theories that were not yet discredited. For example, this meant that, despite knowing lemons were an effective antiscorbutic, Woodall advised that any astringent fluid would be suitable.

Following Woodall’s death, the London Barber-Surgeons continued to examine navy and EEIC surgeons and their chests until the Society of Apothecaries (established in 1617, the forerunners to modern general practitioners) began supplying their non-surgical items from 1703. By 1713, RN medical chests were being examined twice yearly by its own dockyard surgeons and its first dispenser, Henry Blakey, at the Greenwich Naval Hospital.47 Even so, it was not until 1804 that RN surgeons had their drugs supplied at service expense, and even then, they still had to provide their own instruments.48Meanwhile, the London Barber-Surgeons and its successors continued to examine prospective RN surgeons until 1824.49

Although the first wartime seagoing fleet physicians were appointed in 1691,50 medical conditions such as scurvy, typhus and dysentery remained more-or-less unchecked until after the 1740s. Even so, some progress was made: for example, surgeon Patrick Campbell recommended free uniforms to prevent typhus in 1704, although this was not implemented until the introduction of continuous service in 1857.51 In the more immediate term, ships began carrying live sheep to provide fresh meat for the sick, with the manger’s forecastle location providing the site for ship’s sickbays a century later.52,53

Patient care ashore

A previous article describes how Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries forced the closure of nearly all ‘houses of pity’, including the mariner’s ‘masyndews’, from 1536.54 Local parishes, therefore, began funding secular hospitals from the 1550s, supplemented by the monarch’s privy purse, levies (such as those on ships entering Bristol for the local mariner’s hospital), and lay benefactors such as Sir John Hawkins, who provided a ten-bed mariner’s hospital at Chatham in 1594. However, it was only from 1597, when benefactors could make such donations without royal approval, that these hospitals provided even the limited care previously offered by the monasteries.55,56

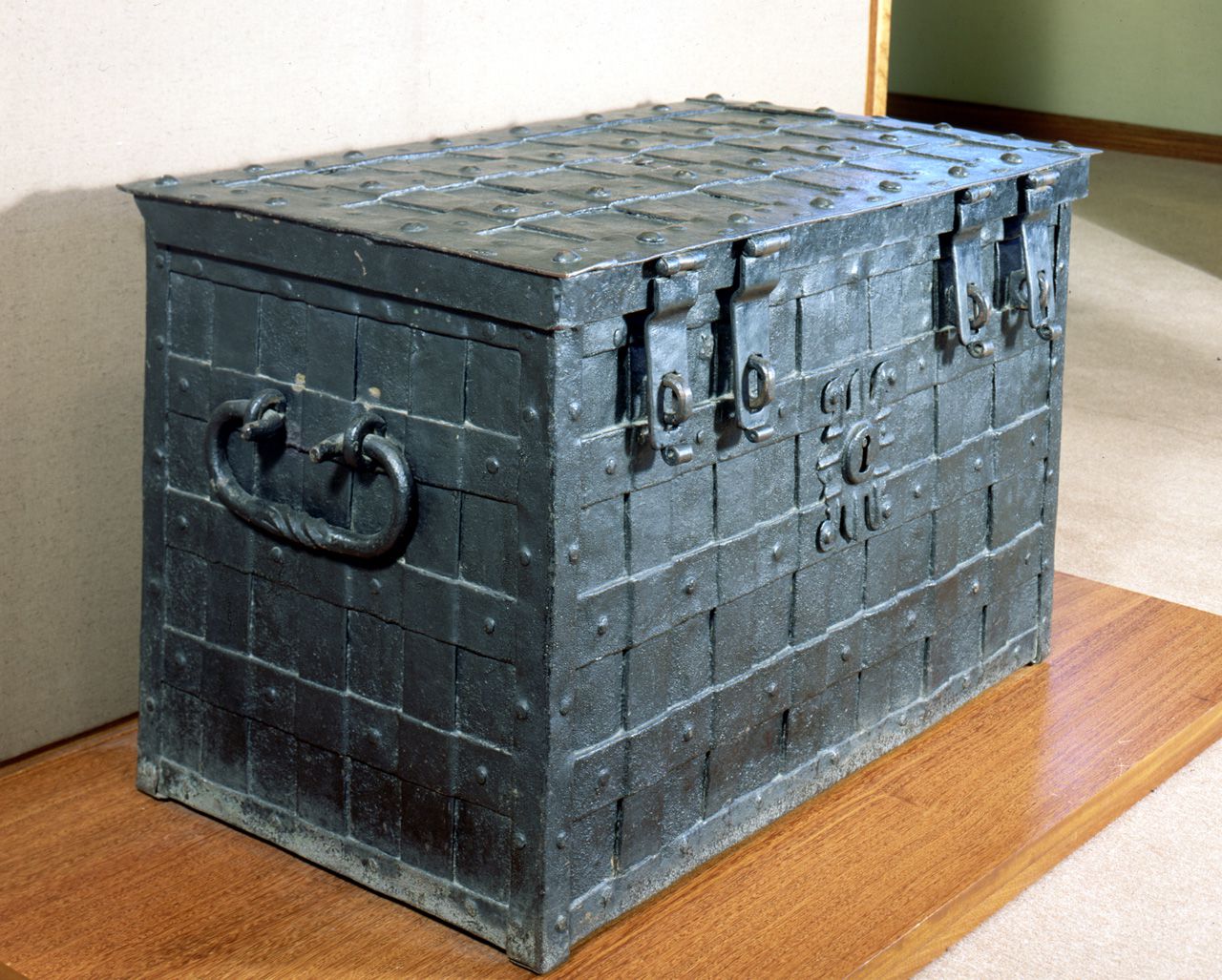

Meanwhile, permanently disabled mariners depended on begging licences or competing with other sick and poor for whatever charitable accommodation remained, until Lord Howard, Sir Francis Drake and Hawkins established the Chatham Chest in 1590. Founded in response to the medical disaster that followed the 1588 Armada campaign, the Chest was an independent mutual benevolent fund to which every seaman in the royal ships (and junior officers from 1626) contributed sixpence a month. The Chest itself had five keys, one being held by the Treasurer of the Navy, whose political power compared to the other key holders meant there was little to prevent corruption. This abuse was also facilitated by low demand. Although disease levels in the Stuart Navy were often overwhelming, the extent to which victims either died or fully recovered meant permanent disability rates remained low until BCas numbers became overwhelming from the 1650s. Applicant numbers were also reduced by applicants having to attend personally until the 1630s when the Chest began funding acute relief, medical and travel costs. Even then, the Board’s decisions were often delayed as it met only once a month and were often arbitrary and inconsistent: although a few received annual pensions of less than £6.13s.4d, they typically only comprised lump sums not exceeding £2 (roughly two month’s wages). Even so, the Chest generally functioned as its founders intended until its merger with the Greenwich Hospital naval pensioner scheme (introduced in 1691) in 1814.57,58,59,60

Figure 9. The original Chatham Chest, built c.1625.61 Note the false central lock (the actual lock is in the lid) and four padlock hasps, the keys to which were putatively held by different people.

Meanwhile, temporarily disabled seamen continued to depend on the medical provisions of the Laws (also Rules or Rolls) of Oléron, introduced in 1190.62 Although ‘Olrums’ had obligated English masters (whether of a King’s ship or private merchantman) to pay for lodging their sick and injured ashore, actual accommodation was often lacking, especially after the demise of the ‘masyndews’. Furthermore, as the navy’s peacetime anti-piracy duties expanded from summer to year-round, more personnel spent more time at sea. Although England’s southern ports had long had to (mostly) cope with ill and injured mariners, the Armada campaign initiated a period where they would be inundated during wartime by mostly DNBI, with the shipboard disease outbreaks also creating epidemics among the townsfolk. In addition, the new ‘line-of-battle’ tactics during the First Dutch War also began to create overwhelming numbers of BCas.

In March 1653, repeated ‘Olrums’ failures led to Parliament sending the London physician Daniel Whistler (1619–1694) wherever he was needed to arrange medical supplies, accommodation (and its payment) and patient transport to London hospitals. By September 1653, he was supported by a four-person Commission for Sick and Hurt Mariners, who, besides naval sick and wounded, was also responsible for prisoners of war and dependents of naval personnel killed in action. Other assistants included the Civil War publisher and nurse Elizabeth Alkin or ‘Parliament Joan’ (c.1600–c.1655), whose efforts rendered herself destitute. While the war’s end brought about the First Commission’s demise sometime before 1659,63 it set the pattern for providing wartime English naval medical services ashore over the next 50 years.

The Second Commission for Sick, Wounded and Prisoners was established on the outbreak of the Second Dutch War in October 1664. Its four members were each assigned a portion of the English coast, with the authority to appoint surgeons, physicians and provost marshals and to requisition half the hospital beds in their area in addition to those in London. Besides the hospitals, this meant the Commissioners had to establish new working relations with the London Barber-Surgeons and its regional counterparts, as well as the Admiralty and the Navy Board. Despite better funding, medical expenses remained excessive: in September 1665, Commissioner John Evelyn (1620–1706) wrote that 5000 sick, wounded and prisoners were dying for lack of food and lodging. Matters were further complicated by high desertion rates among convalescents, thereby exacerbating shortfalls in trained seamen. Although the Second Commission was disbanded at the war’s end, its accounts were not passed by the Treasury until 1671, and its books were not closed until 1675.64

The Third Commission was established on the outbreak of the Second Dutch War in March 1672, with three of its four members having served on the Second. Although many of its roles remained unchanged, greater emphasis was placed on better account keeping and accommodating casualties in hospitals rather than private lodgings, proving cheaper, less amenable to desertion and providing better care. Even so, having established the first English naval hospital (at Plymouth in 1672), financial difficulties led to the Commission’s dissolution in March 1674.65

Figure 10. Plaster statue, shipwrecked sailor, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, 17th century.66

The Third Commission was replaced by surgeon James Pearse (c.1635–1693), who had served at sea twice in the fleet flagship Royal Charles, (including the Battle of Lowestoft in 1665 and the Four Days’ Fight the following year), during which the Duke of York (James II 1685–1688) appointed him Fleet Surgeon General.67 As the Navy Surgeon General (and the Army’s from 1681), Pearse oversaw a period of economy over the next 15 years by having all cases treated on board while using civilian hospitals in lieu of private lodgings whenever possible. To this end, he introduced the first naval medical forms, thereby standardising methods and reducing opportunities for corruption. Pearse also appointed the first naval dockyard surgeons, who received a small wage supplemented by twopence per case, as for surgeons afloat. In addition, he assessed the plethora of Chatham Chest applicants from the previous two wars in the face of its now chronic insolvency.

However, the hospitals began to resist accepting naval patients. Although cheaper for Pearse than private lodgings, they cost the hospitals more than civilian patients because their treatment was frequently more complex, and they tended to be long-term or even permanently disabled. Navy patients also diverted the hospitals from providing medical services for people in poverty. This explains the Plymouth Naval Hospital’s peacetime survival, which was managed by Pearse’s deputy James Yonge (1647–1721), a Mayor of Plymouth and ex-naval surgeon, who had been apprenticed to a sea surgeon at age 10 and gained significant seagoing experience on the Newfoundland fisheries.68

Pearse’s connections with James II led to his replacement by a four-member Fourth Commission in July 1689, shortly after England’s entry into the War of the Augsburg League against France. Having secured the English Channel in 1692, poor-quality victuals soon led to high DNBI rates, which worsened when the RN began operating further afield in the Mediterranean and West Indies. The latter operations against Martinique and Cuba were again ruined by overwhelming rates of malaria and yellow fever, in addition to the usual dysentery, typhus and scurvy.

Meanwhile, the Commissioners spent most of the war managing these cases sans hospital beds, resulting in soaring convalescent desertion rates and private lodging costs.69 Although the long-term savings gained using naval hospitals had been recognised, a lack of capital to buy or build enough to meet demand lasted until the 1740s. An exception was the RN Hospital at Greenwich, donated by Mary II in 1691 to provide accommodation for elderly and disabled seamen, which made more beds available for shorter-term cases elsewhere. Although the hospital was repurposed in 1869, the Greenwich Crown Charity continues to support former RN personnel and their dependents.70,71,72

Figure 11. Greenwich Naval Hospital (the four quadrangular buildings in the foreground; now the Old Royal Naval College).73

During the later part of the war, the Fourth Commission was mostly sidelined by Pearse’s replacement (the Army-centric William III’s royal favourite Willem Van Loon) and the Admiralty dealing directly with the London Barber-Surgeons. On its demise in July 1698, it was replaced by a new Commission of the Register, which did not survive the next outbreak of war in 1702.74

Unlike its predecessors, the Fifth Commission included two physicians among its five members, with Dr Charles Morley previously serving as a physician to the fleet.75 Although the Channel remained secure, the navy’s Mediterranean and West Indies operations were again significantly impeded by DNBI from poor-quality victuals, infectious disease and scurvy. However, the war in Europe meant that, apart from the hospital ships returning these DNBI from overseas, the Commission was predominantly concerned with Army casualties and prisoners. With the war’s end, it was re-established as a permanent Sick and Hurt Board with two members in 1713 and one (Navy Board official Francis Gastny) from 1716 to 1724.76

Conclusion

Although naval DNBI rates under Charles I were often overwhelming, his seamen were somewhat protected from the degradation endured by their Tudor forebears by the secular civilian hospitals that provided better care from the 1590s. Furthermore, as most cases either fully recovered or died, permanent disability rates were initially low enough to be managed (however imperfectly) by the Chatham Chest.

However, during the Interregnum, more ships with bigger crews travelling further distances over longer periods led to increased DNBI, while new tactics during the Dutch and Spanish wars created more BCas. These combined in 1652 to overwhelm the ‘Olrums’ provisions that had existed for over 400 years, which led to the first of five wartime Sick and Hurt Commissions. Despite usually lacking medical qualifications, the Commissioners (and Pearse) found that hospitals were less expensive, provided better care and were less amenable to convalescent desertion than private lodgings. However, they also faced increasing resistance therefrom, because naval patients stayed longer and cost more to treat than civilians. Although these considerations led to the first English naval hospitals, the high capital costs to buy or build them before these savings could be realised ensured an ongoing dependence on the older alternatives well into the 18th century.

Meanwhile, at sea, most seamen now recognised the need for high hygiene standards while the EEIC had begun demonstrating the health benefits of better-funded ships and victualling. The EEIC also incidentally provided permanent employment for seagoing surgeons, who were required to document their experiences for future reference. Notwithstanding official delays of up to a century, the navy typically gained many of its medical lessons somewhat sooner informally from the EEIC via the itinerant employment of English mariners and surgeons between the two organisations. Improvements within the navy included the first allowances for medical stores in 1626, having at least one surgeon’s mate for each surgeon from 1652, and introducing bespoke hospital ships in 1655. Otherwise, therapeutics had somewhat improved and, by the end of the century, it was accepted that sea surgeons needed the skills to treat non-surgical illnesses.

However, although Woodall and Pearse had independently demonstrated the benefits of a focal naval medical authority, their largely single-handed efforts became false dawns, whose advances were not regained until 1832. This, combined with the ongoing limitations posed by humoural theories of disease, meant the Elizabethan DNBI scourges remained largely unchecked until the 1740s.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the RAN or any other organisations mentioned.

Please specify the URL of your file