N Westphalen

Introduction

Previous articles describe the development from prehistory to the end of the Roman Empire, of a cycle whereby increasing trade necessitated larger and more efficient ships to transport merchandise and better weapons to defend or attack them; both of which facilitated more trading opportunities. It was not until the 18th century that Western medicine had developed sufficiently for its role as an enabler of this cycle to be recognised, which made possible the European settlement of Australia.

While the technical developments in weapons, ships and medicine driven by this cycle often developed independently in multiple regions worldwide, they remained closely linked throughout Western history in particular. This article describes, for better and for worse, the technical and other developments in warfare, ships and medicine during the Viking Age from 500 to 1200 CE.

For the purpose of this article, the term ‘Viking’ refers to people who left Scandinavia, while ‘Norse’ refers to those who stayed behind.

Viking warfare

The factors driving the Viking expansion beyond Scandinavia remain a subject of debate. Possibilities include the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE; retaliation against the expansion of Christianity; agricultural failures within Scandinavia; and a lack of land for second sons and beyond to inherit. However, the focus on raiding rather than other more peaceful alternatives suggests that a lack of commodities for the Vikings to trade, combined with a plethora elsewhere, provided at least some of the initial motivation.

Scandinavian society did not form the unified kingdoms of Norway, Sweden and Denmark until near the end of this period. Until then, individual leaders ranging from local chieftains to earls and kings, teamed up to conduct hit-and-run attacks throughout Europe in search of slaves and places to plunder. These eventually led to the establishment of overwintering bases for further raids, resulting in the founding of several full-fledged Viking territories in the Baltic, Russia, Britain, Ireland, France and southern Italy. The Viking Age ended with their progressive acceptance of Christianity and assimilation within the populations they had first raided and then settled among.

Viking warriors closely identified with their swords, which were difficult to make and therefore rare and expensive. They were family heirlooms with names such as ‘Leg Biter’ and were frequently richly decorated using silver and/or copper inlay to form beautiful geometric patterns, animal motifs or, in the late Viking Age, Christian icons. At around 900 mm long, Viking swords were designed for oneon-one combat, where added length gave the user an advantage compared to the old Roman gladius, which was designed for fighting in densely compacted formations.

Vikings also used circular wooden shields edged with leather, with a central boss of iron to protect the hand. These were large enough to cover the body yet light enough to be used offensively (for example by ramming the edge into their opponents’ face to break noses, jaws and teeth). They also used mail armour, which was lighter and allowed greater mobility than plate armour.

Other Viking weapons included axes, daggers or short-swords (the seax, the signature weapon used by the Saxon tribes that invaded Roman Britain from 400 CE), spears, and bows and arrows. These were generally (but by no means always) used by poorer warriors who could not afford a sword.

Left: Viking helmet found Gjermundbu, Norway 1943, dated c1000 CE. Note the absence of horns.

Right: Replica Viking spangenhelm helmet.11 Note the nose guard.

Viking swords—c750–950 CE—found in the River Meuse near Den Bosch, Aalburg and Wessem in the Netherlands

Note the decorations on the pommels, in particular the gold inlay on the uppermost sword.

Left: Original shield from the Gokstad ship found 1880, dated c890 CE.13 Note the wooden planking and iron boss in the middle.

Right: Replica Gokstad shield (front). Note the leather binding to protect the edge and hold the planks together.

Bottom: Replica Gokstad shield (rear.) Note the central handgrip is covered by the boss.

Right: Gjermundbu mail shirt (closeup). Each ring is interlinked with four neighbours. There are two types of ring: one solid and one riveted. A shirt this size would have had up to 15 000 rings and weighed about 6kg.

Replica Viking seax, c700 CE.

Axe head found at Mammen, Denmark, found 1868, dated 971 CE.20 Note the silver inlay, suggesting its probable use as ceremonial purposes.

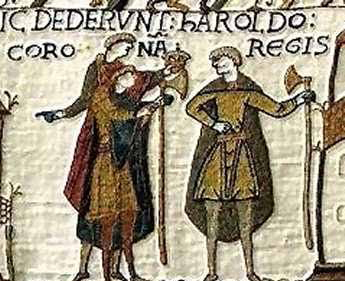

Battle axes, Bayeux Tapestry, 1100 CE.21 Harold Godwinson is standing between two axes (one his own), while being offered the crown of England after the death of King Edward the Confessor in January 1066. Note the long handles.

Viking ships

The Scandinavian history of shipbuilding began in the Neolithic period (12 000–4500 BCE), although there is an ongoing debate as to whether the first boats began as dugouts to which additional planks and ribs were added, or as reindeer hides stretched over an antler or bone (later wooden) frame. The oldest plank-built boat in northern Europe is a double-ended 22-man paddle canoe, found in a bog at Hjortspring in southern Denmark in 1921. Dated to c350 BCE, she had two side planks on each side sewn to a central plank and two block stems, held together with combination ribs/beams with the latter acting as rather perch-like thwarts.

The Nydam ship, discovered in 1859 and dated to c310 CE, is considered seaworthy enough to have undertaken attacks on Roman Britain. She still has a central plank rather than a proper keel, with five strakes on either side held together with iron rivets, making her the oldest known clinker-built vessel. The ends of each strake are inset (‘rabbeted’) to the bow and stem pieces. There was no sail, but places for 30 rowers on proper thwarts.

In 1939, the remains of a Viking ship burial were found at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, UK, dated to c625 CE. Although the wood had not survived, the outline of the ship was preserved in the soil. As it is unclear whether she could be sailed as well as rowed, a replica was under development at the time of writing to ascertain her rowing and (possible) sailing qualities. Likewise, it is also unclear whether the Kvalsund ship, discovered in Norway in 1920 and dated to c690 CE, could also be sailed as well as rowed.

Hence, the earliest Viking ship known to carry sail is the Oseberg ship, which was discovered in 1903 and dated to c820 CE. However, the Gokstad ship (discovered in 1880 and dated to 890 CE), is probably a more representative active seagoing vessel, as demonstrated by several replicas that have undertaken open-ocean voyages to as far as North America. The Gokstad ship has 16 oar ports on each side that could be shuttered, and 32 shields, which indicated her use for warlike purposes.

Viking warships were valuable, not just for their prestige and monetary value but also their future utility. Although such battles were rare, Viking naval combat therefore entailed gaining control of an opponents’ ship (and their valuables) by handto-hand fighting without damaging the ship or her gear.

To this end, Viking sea battles were usually fought in protected fjords or otherwise sheltered waters, where ships could be rafted together to form floating ‘islands’. Helmsmen manoeuvred for the most favourable position to board the outermost ships, while the crews shot arrows and spears as they drew together. As each defeated ship was cleared of her crew, she was set adrift while the victors boarded the next ship making up the ‘island’. Meanwhile, smaller boats swarmed around the main battle to finish off anyone who ended up in the water.

However, the key to Viking warship effectiveness pertained more to their combination of shallow draft and enhanced seaworthiness, to enable fighting ashore. The former enabled Vikings to navigate inland waters that could not be reached by their opponents, while also allowing them to quickly land their crews and pick them and their loot up afterwards; the latter gave them the strategic mobility to attack overseas shore targets that otherwise could not be reached from home.

These attributes led to the Vikings developing oceangoing cargo ships or ‘knarrs’ (also ‘knörrs’) from 1000 CE. These used the same clinker-built construction as warships, but with heavier lines for sailing instead of rowing. Knarrs became the basis of the northern European ‘cog’ ships from 1200 CE.

A key limitation regarding Viking open-ocean voyages relates to their navigation. As they had no compasses, charts or speed logs, it seems likely they relied on hopping between known landmarks (facilitated by chants and rhymes as aide-memoires), aided by their knowledge of sun and stars, wave, wind and cloud patterns, and marine flora and fauna. Vikings also restricted their operations to the summer months, noting that their ships had no shelter for their crews, and—notwithstanding their enhanced seaworthiness—the fact that they were still essentially large open boats that were susceptible to being swamped and sunk.

Hjortspring boat found 1921, dated c350 BCE, National Museum of Denmark.

Hjortspring boat model, National Museum of Denmark. Note the combination rib/paddle thwarts. The purpose of the projections at either end remains unknown.

Replica Viking Age iron boat rivets and washers. Each rivet was inserted from the outside of the hull while redhot so the bottom edge of the uppermost plank or ‘strake’ overlapped the top edge of the strake below. A washer was placed over each rivet inside the hull and hammered in place.

Nydam ship, found 1859, dated c310 CE, State Archeological Museum, Schleswig, Germany.33 Note the clinker strakes.

Sutton Hoo ship burial site found 1939, dated c625 CE. Note that, although the wood had not survived, the clinker construction of the hull and the ribs have been preserved in the soil. Also, note the iron rivets.

Nydam ship replica Nydam Tveir. Note the steering oar on the starboard quarter and absence of a sail.

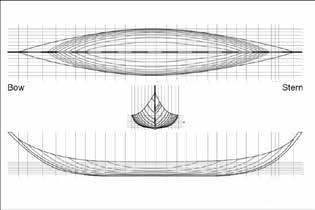

Replica Sutton Hoo burial ship lines.

Model, Kvalsund ship, found 1920, dated c690 CE. Note the rowlocks and thwarts, and absence of a mast and sail. The bow is to the left.

Gokstad ship found 1880, dated c890 CE. Note the oar ports, loose deck planking and absence of decorative carving. The bow is to the right.

Oseberg ship found 1903, dated c820 CE. Note the bow decorations, loose deck planking and absence of rowing thwarts.

Gokstad ship oar port covers.42 The port slot at 10 o’clock in the upper photo is for the oar blade.

Oseberg ship closeup. Note the stem carvings and rivets

Gokstad replica Viking at Chicago after crossing the Atlantic, 1893

‘Skuldelev 1’ knarr, one of five vessels found near Roskilde, Denmark in 1962, dated 1030 CE.44 Note the broader beam and heavier lines compared to the Gokstad ship.

Replica Skuldelev 1 knarr Ottar. Note the absence of oars—or crew shelter.

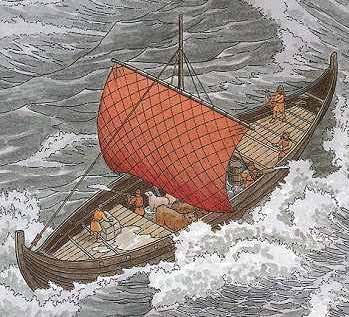

Representation of a knarr in bad weather. Note the absence of crew shelter, the knee-deep water in the cargo area amidships—and the two bailers.

Viking medicine

During the pre-Christian Viking Age, most Scandinavians relied on self-aid or local people deemed to have supernatural abilities who inscribed magical runes combined with chants and charms. One Norse saga describes how a young woman’s health was at first ruined through the use of improper runes, and then restored by correct ones carved on whalebone and placed under her bed. Magic could also prevent healing: in one saga, the warrior Eidur says that wounds inflicted by his sword ‘Sköfnung’ would not heal unless they were rubbed with Sköfnung’s healing stone.

To these ends, Norse poetry had numerous charms for the maintenance of health in daily life. These originated from Germanic prehistory, when wisewomen and conjurers recited their incantations against the spirits of disease, while sufferers from diverse illnesses called upon gods such as Thor, Odin or Freyr for a return of health.

Notwithstanding their reliance on magic, burial site studies suggest that at least some of the population had a long life and good health. For example, skeletal remains from Skeljastadir in Iceland from 1000 to 1200 CE indicate that the population was generally healthy. They also show that their teeth show considerable wear but few caries, most likely because their diet had coarser food, fewer refined foods and much less sugar compared to modern western diets.

Nevertheless, consistent with the infectious disease hazards inherent to the first settlements elsewhere, epidemics of smallpox, dysentery and leprosy are also recorded in the Norse literature and confirmed by their burial sites. These epidemics followed

wherever they went; a mass grave at the winter camp used in 873–874 by the Viking Great Army at Repton England mostly consisted of adult males, and although several had battle injuries, many of the remainder had likely succumbed to disease.

The Vikings’ fatalism towards such cases is demonstrated by a saga describing a protracted period of disease at Lysufjordur in Greenland, where the role of the healthy was limited to helping the sick prepare for death. Another saga tells the story of a man who had booked passage from Iceland to Norway, who was prevailed upon to take a relative with leprosy with him. He took his sick kinsman ashore and killed him, before returning to the ship to take his passage.

From such beginnings, the Vikings’ progressive conversion to Christianity also brought acceptance of Roman medicine, as advocated by Galen of Pergamon (129–c216 CE). A previous article described how Galen had studied in Smyrna and Alexandria and worked at a gladiator school before becoming a prolific writer of medical treatises that were translated into many languages.

Although he had gained considerable anatomical knowledge by treating wounded gladiators, a ban

on human cadaver dissection from c250 BCE until after 1300 CE meant Galen’s research was otherwise limited to Barbary apes and pigs. He erred regarding the role of the veins in returning blood to the heart, while a misunderstanding of his writings regarding the need to drain abscesses led to a belief that ‘laudable pus’ was a positive sign of wound healing.

Furthermore, Galen supported the Greek Corpus Hippocraticum regarding the idea that illness was caused by imbalances of the four bodily fluids (or humours) of phlegm, yellow bile, black bile and blood. This idea was coupled with the four qualities of heat, cold, wet and dry, which underpinned all treatments for the next 1500 years. Among other shortfalls, this led to the use of bloodletting as a treatment and the view that diseases such as malaria were caused by bad air from rotting animal and plant matter.

The later Viking Age, therefore, saw medicine becoming a vocation and profession on comparable terms as the rest of Europe. The best-known Viking physician was the Icelander Hrafn Sveinbjarnarson (c1166–1213), who was highly regarded for his skills.

Hence, medical treatment included lancing, cleaning wounds, anointing, bandaging, setting broken bones, preparing herbal remedies (including local herbs) and midwifery. The Icelandic Grágás (‘Grey Goose’) law book dated prior to 1262, states that one must hold harmless a person who bled or cauterised someone for the good of their health, suggesting these treatments were also used.

The saga literature and forensic studies of skeletal remains both show that people survived serious battle injuries. They also confirm that surgery was performed from time to time, some of which was successful.

The sagas tell of several forms of battlefield first aid, such as throwing shields over the wounded to protect them from further injury and calling pauses during longer fights to allow men to bind their wounds. One saga describes how a warrior was struck by a blow that cut through his shoulder such that his lungs fell out. He was bound up and cared for until the battle was over and then carried home for treatment.

Another saga described an unusual diagnostic technique for abdominal wounds, where a casualty was given a hot broth containing leeks and onions among other herbs. The smell of the broth from the wound indicated a perforated viscus, thereby confirming it was fatal. Some skeletal remains confirm such stories by showing both healed and unhealed battle injuries in the same skeleton.

Skull split open by a sword slash, c1100 CE. This rather graphically demonstrates the need for helmets.

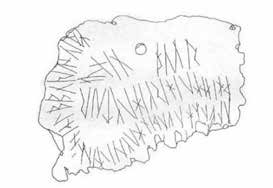

Skull fragment with runes, worn as a protective amulet, found Ribe, Denmark, dated c700–800 CE.

Skull fragment sketch showing the following runes:

‘Ulf and Odin, and High Tyr, is help for Bur, against these pain and Dwarf sword, Bur’

Conclusion

The Scandinavians’ initial focus on raiding rather than more peaceful alternatives suggests that a lack of commodities to trade provided at least some motivation to engage in opportunistic attacks throughout Europe in search of plunder and slaves. Over time, these raids led to the establishment of seasonal and then permanent Viking settlements, which were eventually assimilated into the local populations.

This process was facilitated by the Vikings’ ability to move large numbers of men over long distances for extended periods. This was based on the development of ships of shallow draft that nevertheless could make oceanic voyages. The former capability allowed the Vikings to raid shore targets that were otherwise inaccessible by sea, yet preventing counterattack by seagoing opponents, while the latter gave them the strategic mobility to strike such targets at long ranges from home. It should also be noted that none of this would have been possible without an excellent understanding of logistics.

The development of overwintering bases led to permanent Viking settlements, which required ships of progressively increasing cargo capacity. These ships led to the settlement of Iceland, Greenland and North America, and became the basis of northern European shipbuilding from 1200 CE. However, the Viking settlement of North America was abandoned, most likely in the first instance because their ships still lacked a true all-weather seagoing capability, while the absence of oceanic navigation aids limited their crews to sophisticated yet still inadequate coastal navigation techniques. Furthermore, the generally comparable weapons technology of Viking settlers and the Native American populations opposing them, combined with the latter’s force of numbers, probably made the formers’ presence unsustainable.

Subsequent transatlantic voyages from the mid15th century onwards suggest that from a medical viewpoint, Viking voyages probably did not entail enough time at sea for their crews to develop deficiency disorders such as scurvy. It also seems likely that their crew sizes particularly for the knarrs—were generally too small for infectious diseases such as typhus and dysentery to pose a threat, except when they were assembled in large numbers for extended periods ashore.

Rather than the mutually supportive close-quarter tactics used by the Romans and Greeks, the Vikings’ focus on raiding led to a high level of reliance onthe fighting skills of individual warriors, resulting in weapons that were primarily intended for oneon-one combat. Although swords were therefore the weapon of choice, their scarcity and expense led to alternatives such as axes, short-swords, spears and bows and arrows.

Viking sea battles were rare and were generally fought in the same manner as ashore, apart from the victors cutting each ship adrift from their attached neighbours before boarding the next one. Unlike the Greeks and Romans however, one of the Vikings’ priorities was to capture their opponents’ ships intact. The ongoing more-or-less universal inability to swim meant that ending up in the water would have been fatal, even without fighters in small open boats to finish them off.

Therefore, the only wounded would have been those of the victors. Although the proximity to shore would have greatly facilitated their treatment, the Vikings’ initial reliance on the supernatural led to a highly fatalistic attitude to health care, until their acceptance of Christianity brought with it Galenic medicine on comparable terms as the rest of Europe. Like the Romans, Viking surgical capabilities—if not their anaesthetics, analgesia and post-operative wound care—would have then compared fairly well with modern practice, at least for limb injuries and minor wounds. However, like the rest of Europe, their acceptance of Galen’s humoural theories (in particular the miasmatic theory of infectious disease) continued to stymy medical science for another 300 years.

Author

Dr Neil Westphalen graduated from Adelaide University in 1985 and joined the RAN in 1987. He is a RAN Staff Course graduate and a Fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine and the Australasian College of Aerospace Medicine. He also holds a Diploma of Aviation Medicine and a Master of Public Health.

His seagoing service includes HMA Ships Swan, Stalwart, Success, Sydney, Perth and Choules. Deployments include DAMASK VII, RIMPAC 96,

TANAGER, RELEX II, GEMSBOK, TALISMAN SABRE 07, RENDERSAFE 14, SEA RAIDER 15, KAKADU 16 and SEA HORIZON 17. His service ashore includes clinical roles at Cerberus, Penguin, Kuttabul, Albatross and Stirling, and staff positions as J07 (Director Health) at the then HQAST, Director Navy Occupational and Environmental Health, Director of Navy Health, Joint Health Command SO1 MEC Advisory and Review Services and Fleet Medical Officer (2013-2016).

Commander Westphalen transferred to the Active Reserve in July 2016.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the RAN or any other organisations mentioned

Corresponding Author: Neil Westphalen,

neil.westphalen@bigpond.com

Authors: N Westphalen 1,2

Author Affiliations:

1 Royal Australian Navy Reserve

2 Navy Health Service, C/O Director Navy Health