W Maddocks

Background: Skill fade is a potential issue in any military medical training environment. Within the current New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) medic training programme, emergency skills are taught and practised in a simulated environment but are rarely used in real-life situations. As there is infrequent exposure to emergency situations during training, there is a potential for skill fade to occur with some emergency techniques. One such technique is the use of supraglottic airway devices (SADs) as used in the prehospital emergency environment from both a military and civilian context. However, an optimum training interval has not been clearly defined for this skill within a military medic context.

Purpose: This literature review explores the issue of skill fade, in particular with prehospital emergency airway management using SADs. This review can guide the framework for an evaluative study, which could be conducted in a military medic training context to help determine the extent of skill fade and how it could be mitigated through manipulation of training intervals.

Material and methods: Literature was reviewed from military and civilian prehospital contexts to identify key extant studies in the use of SADs. The review has been placed in a wider context of skill fade within emergency care training in general as well as recognising the unique military contexts in which prehospital emergency care is provided.

Discussion: Several studies identified that the rate of skill fade within emergency care is consistent across several medical disciplines, with skill fade occurring from around eight weeks and peak decline at six months. Different instructional methods do not seem to reduce skill fade when used in isolation, suggesting a mixed- method approach is needed with regular retesting to ensure competency in the use of SADs. The review did not identify any research that specifically explored the issue of skill fade within NZDF medic training; however, the information provided would assist further research in this area.

Conflict of interest: The author does not have a conflict of interest. Preliminary planning of this literature review and potential research commenced while the author was employed by the NZDF as a civilian medical lecturer at the Defence Health School at Burnham Military Camp in Christchurch. The paper was completed while employed as an academic at Canterbury University. No payment or royalty has been received. All expenses incurred in retrieving literature was met by Canterbury University.

Introduction

The training of military medics worldwide varies from country to country, as is the exposure to life- threatening emergencies in both a tactical or non- tactical environment. As with other technical military skills, continuous training is undertaken to guard against skill fade.1 In simple terms, skill fade is when a clinician becomes ‘rusty’ in their practice due to non-use of a skill over an undetermined period2 and is of particular importance in procedural skills where there is a set sequence to follow for the skill.3 Early educational psychology research has identified that the human brain can recall up to seven procedural steps from memory depending on complexity.3 Understanding these principles formed the basis of the development of the User Decision Aid (UDA) model by the United States Army Research Institute (USARI), which helped predict skill retention and develop the schedule for refresher training of skills.4

Emergency airway management is a key part of the military medic’s toolkit in the prehospital setting, and while the use of an endotracheal tube (ETT) is considered the gold standard for airway security, it is recognised as a difficult skill to learn and remain competent in the prehospital setting. In addition, it requires particular equipment and drugs,5 which are not practical in the military prehospital context. Using a supraglottic airway device (SAD) is easier than an ETT with a higher degree of accuracy of insertion when used by non-anaesthetists.5 It is the recommended airway management for use in a tactical setting.6 In a prehospital civilian setting, the error rate of ETT insertions by paramedics can be as high as 25%,7 and for competency to be achieved it needs to be conducted at least 25 times on real patients.8 Because of this high error rate, it is not the preferred airway management of choice in the prehospital setting for paramedics. Therefore, in the prehospital civilian environment, ETT insertion is considered an advanced skill, taught to a selected few advanced paramedical practitioners to reduce skill fade.8

Within New Zealand, tri-service military medics are trained by the NZDF Defence Health School (DHS), and graduates are responsible for providing comprehensive medical care of all personnel, including routine primary healthcare of personnel, both in a domestic or deployed operational environment. In addition, they are trained in emergency and tactical care for use in humanitarian and disaster relief (HADR) and deployed tactical environments as required by the New Zealand Government9, 10 where they follow the guidelines of Tactical Combat Casualty Care.11 Since 2017, all NZDF military medic training has occurred solely within the NZDF environment using a range of instructional methodologies, including high fidelity simulation-based training. The potential use of simulated, virtual and augmented reality in medical training has an associated perceived reduction in training cost, which suggests a revision of some of the core principles to mitigate the risk of skill fade effectively without increasing the training burden as mentioned previously.2

Currently, NZDF medic trainees do not receive any clinical experience in civilian emergency healthcare such as emergency departments or ambulance services while training.12 With the ever-present potential of a life-threatening emergency with military personnel while at land, sea or in the air, a NZDF medic must be able to respond appropriately and sustain life until transfer to a civilian provider. Recent incidents (2018 and 2019) have occurred in New Zealand where military personnel have sustained serious injuries during live firing exercises.13, 14 The NZDF medics attached to these units were responsible for providing immediate lifesaving care until transfer to advanced care occurred.

Emergency medical care can be provided to civilians by NZDF medics during humanitarian, disaster relief (HADR), when a state of emergency is declared or when life or limb is in danger.10, 15 Examples include; the provision of disaster aid and care to NZDF staff and casualties during the 2011 Canterbury earthquakes;16, 17 provision of lifesaving emergency care by three recently graduated medics at a serious car accident outside a military base;18 and finally, a medic, travelling as part of a military convoy, administered emergency care to a casualty who was having an anaphylactic reaction while driving.19 The March 2019 terror attacks in Christchurch also had medical staff at nearby Burnham Camp on standby to assist if required.20 These incidents highlight that NZDF medics could be required to use their emergency skills in unexpected contexts outside of their routine NZDF work, and thus need to be able to provide this care appropriately.

Aims

- Explore the issue of skill fade of emergency skills within a prehospital context as performed on adults by trained providers; and

- Identify key research in the area of skill fade, relating to the prehospital (non-deployed) military medical context, in particular with relevance to the use of supraglottic airway devices (SADs).

This review can guide the development of a framework for an evaluative study in the military medic training context to help determine the extent of skill fade and how it could be mitigated through appropriate training intervals and instructional methodologies.

Method

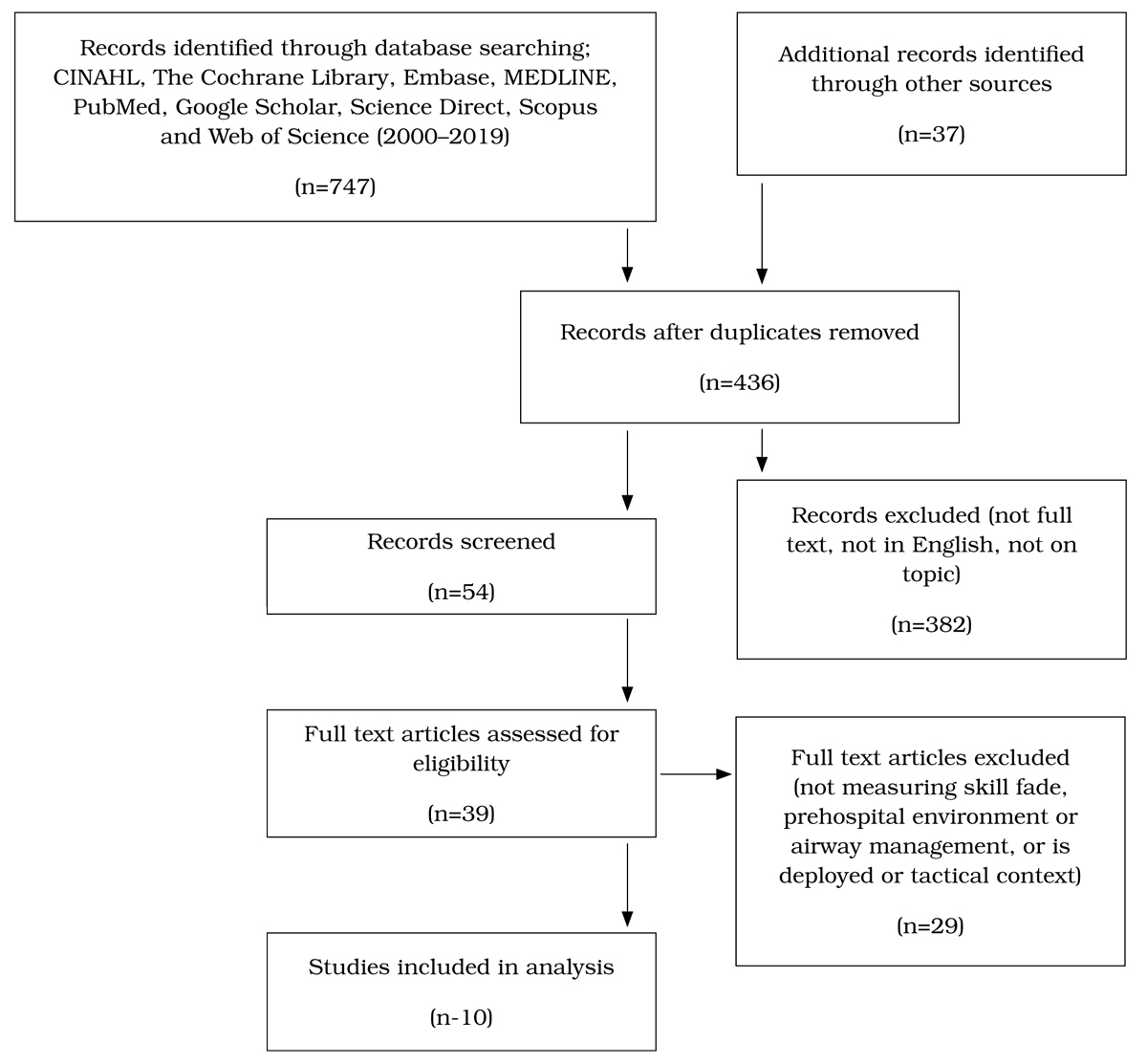

A literature search was conducted following the PRISMA (www.prisma-statement.org) guidelines, using the University of Canterbury library multisearch function. Search terms included; ‘skill* fade*’, ‘skill* retention’, ‘train* interval*’ and ‘cognitive decline’ ‘prehospital* emergency care’, ‘use of SADs, ‘supraglottic airway devices’, ‘airway management’.

Figure 1 summarises the search process.

Inclusion criteria included the date range of 2000– 2019, as this was when SADs were introduced into patient care; any use of SADs in the prehospital setting; adult resuscitation training; and military medic training. Exclusions were the use of SADs in the tactical space and effects on survival; studies conducted on children, live tissue or animals; studies that did not include SAD use; and studies involving routine inpatient use of SADs (e.g. the operating room) The final articles were added to NVIVO software for scanning, coding and duplicate removal. Finally, a manual crosscheck of reference lists was conducted to ensure all possible articles had been sourced. For the purpose of consistency throughout this review, the term ‘skill fade’ encompasses all terms used in the literature.

Assumptions made about each study were that they replicated, as close as possible, a simulated emergency scene and that all testing was conducted on adult mannequins unless indicated otherwise. Information on possible bias in studies was checked and considered in the interpretation of the findings by the author.

Results

Table 1 summarises the findings of the 10 research articles reviewed.

| Authors | Year | Number/type of participants | Methodology | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al (26) | 1998 | 211 military GPs | Theory testing and retesting of ALS and CTLS | Linear skill decline |

| Barlow et al (27) | 2018 | 14 Military GPs | Focus group | Felt under prepared to respond to emergency |

| Bukiran et al (28) | 2014 | 225 civilian ICU/emergency nurses | Theory testing BLS and ALS | Skill fade by six month, emergency nurses retained skills longer |

| Kenward et al (21) | 2017 | 41 military and civ senior nurses | Delphi study until consensus | Confirms risk of skill fade, highlights unique need of military nurses |

| Mitchell et al (30) | 2018 | 63 deployed personnel | Survey | Perception of confidence low to perform BLS-need to continue refreshers on deployment |

| Inglis (30) | 2019 | Deployed navy number not stated | Survey | Perception of confidence to perform BLS increases with 3 or more refreshers |

| Jensen et al(31) | 2019 | 795 high school students | Observational | Skill fade by four–six months |

| Sun et al (34) | 2017 | Sim based training | Literature review | Skill fade begins at four weeks, combined SBT and non SBT more effective |

| Hensel et al(33) | 2017 | 285 non-medical soldiers | RCT | Mixed methodology best instruction, skill fade by three months |

Defining skill fade

Skill fade occurs in a continuous downward scale, initially quite rapidly, then more gradually as the more time has elapsed between initial training.21,22 Overlearning – where a new skill is taught and practised repetitively beyond initial mastery to the point of being ‘automatic’23 – is a core part of emergency skill learning.24 In a military context, skill decline was fastest in the first few months after learning the skill and motor skills decline faster than knowledge skills.22 Poor self-perception of ability can also increase a decline in performance.2 Despite various efforts to identify the peak time of skill fade, factors such as the actual skill, experience of the operator, teaching methodology, training time, use of simulation and repeated practice, and actual use of the skills all have an impact on the degree of skill fade.2, 22

In an extensive literature review of skill fade across a range of military skills, the Canadian Army note that a clear distinction needs to be made between skill retention, which they note, is the ‘sustainment of skills as learned behaviours and procedures over long periods of time without practice’25 p.14 and reduced performance, which can be due to degradation of several processes underpinning the skill, such as motor skills, cognition or accessibility of memory. This distinction is important to considerwhen trying to predict and remediate skill fade or depreciation.25 While this review did not specifically cover military medical skills such as emergency airway management, the theoretical constructs presented in this review would help future researchers exploring skill fade within a military context.

Skill fade within a theoretical context

Skill fade includes cognitive knowledge recall as measured by the first study, which compared two groups of military physicians from the Israeli Defence Force.26 In this study, two groups were asked to complete theoretical tests on recall of airway management similar to their initial training (n=211). The first group (n=138) had completed Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) training, and the second group (n=73) had completed Combat Trauma Life Support (CTLS) training in the previous 3–66 months. This study noted that the IDF physicians are mainly reservists, and are most likely not exposed to trauma in their day-to-day work but are required to be able to deliver advanced trauma care in their role as military physicians. The recall test results were then compared with their original test scores, which had a pass mark of 80%. A refresher course was deemed necessary when 50% of participants scored less than 80% in the test. The skill fade was similar in both groups and occurred in a linear fashion with all participants retaining 80% or higher scores up to 52 weeks post-training, and the point at where 50% of participants’ scores were below 80% was 192 weeks. While age was stated with a mean age of 39 years (+/- 6.2), there was no mention of gender in the analysis.26 This study contributes significantly to the notion of skill fade as it relates to theoretical recall over an extended period, which would help in the development of guidelines for refresher training.

This situation is similar in the UK where military GPs are infrequently exposed to emergencies. Fourteen participants were interviewed in focus groups to understand their perception of preparedness for acute trauma care; the respondents indicating they felt underprepared as skills did fade over time.27 A detailed response to this article supported the need for continued work in this area,24 further supporting the concern of the uniqueness of the military medical environment where both routine care is provided for as well as the need to be skilled in advance emergency care. While this work was conducted on a focus group, further exploration would need to be undertaken to establish if these perceptions were actualised in practice.

A similar type of study was conducted in Turkey, assessing nurse’s (n=225) theoretical knowledge of combined Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Life Support (ALS) at three intervals after initial training.28 The aim of this civilian study was to see if retention of learning related to BLS and ALS was sustained over time. All participants were pre-tested and achieved a mean score of 12.6/25, which increased to 21.1/25 post-training. (A pass mark of 18/25 was required). Four tests were administered over the next 12 months, with 149 nurses completing all four tests (N=149). Results were mixed at the six-month testing interval, with male nurses (n=15) statistically not achieving an average pass mark compared to the females (n=134) (p=0.07). Those nurses who worked in areas such as emergency, critical care and medical care still achieved pass marks in the first three tests; however, by 12 months, only emergency care nurses achieved a pass mark. In their discussion, the authors noted that the optimal repeat training interval based on other studies is probably between three and six months, but, in reality, this may not be possible in hospital settings.28 While this study was not in either a military or a prehospital context, it has been included here to show the effect of time on skill fade as well as the effect of repeated skill exposure through the work environment in the reduction of skill fade.

In an attempt to understand and mitigate the risk of skill fade and to find the optimum training needs for British military nurses, the return to practice and clinical contact time needed by British military nurses was explored in a Delphi panel study.21 This methodology aimed to achieve consensus from 41 senior military nursing and NHS staff on a number of statements around the length of weekly clinical time needed to remain competent. All panel members recognised the real risk of skill fade if there is significant time away from clinical practice. After eventually achieving consensus policy was developed to ensure maintenance of both military and clinical skills.21 This process enabled personal bias to be removed from a wide range of experts until a consensus was reached and makes a significant contribution to the knowledge around the military medical/nursing context of the balance needed in maintaining competency and military skills.

Another UK study explored the need for continued refreshers for deployed medical personnel who are on prolonged deployment.29 Sixty-three currently deployed UK medical professionals were surveyed who had been deployed for between three and six months at a level 2 hospital in South Sudan (n=55). While all had undergone BLS before deployment, 84% felt that further practice in BLS should be initiated on deployment, especially on a contingency deployment where patient numbers may be low or unpredictable, and the risk of skill fade was higher.29, 30 This perceived confidence and the effect on potential skill fade was explored in a very recent study within a deployed naval context.30 The authors tried to determine the impact of personnel confidence in the ability to give BLS on a ship-based emergency and found that non-medical personnel who had attended three refresher sessions at an unknown interval felt more confident of performing BLS than before.30 These two studies address the potential risk that the perceived lack of confidence by military personnel to respond appropriately to an emergency in a difficult location. Undertaking regular refresher training while on deployment enhances confidence, and this needs to be factored into planning of training.

Skill fade of procedural skills

The impact of the quality of training on skill retention, both in terms of resources and personnel providing the training, was explored in a nationwide Danish study of civilian CPR courses.31 The authors reviewed 16 training publications provided by different agencies who taught bystander CPR to civilians according to European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines. In addition, researchers observed courses and a selected number of participants were followed up and retested at between four to six months post- course. The authors found that not all necessary content was covered in the books and that people performed better if the class size ratio was 6:1, and if the instructor came from a healthcare background. When retested at between four to six months, the skill retention of the practical skills was poor as was retention of knowledge, which had not been included in the book.31 This study highlights the importance of having clear written material that is effectively reinforced with practical learning and hands-on practice in small group settings. These findings seem to support a slightly earlier study,32 which tested skill retention of CPR in high school students. This study consisted of 795 high school students with a median age of 15 who were allocated to either one arm who had learnt CPR three months previously (n=431) or the second arm who had learnt it six months previously (n=364). Regardless of which arm, both groups had poor skill and knowledge retention, with more than 65% demonstrating errors in techniques, especially with chest compression.32 While this particular study does not specifically include the use of SADs, it continues to add substance to the notion that skill fade in emergency skills occurs between three and six months. This time frame being consistent with other studies measuring CPR.22, 24, 25, 28, 29, 33

The use of simulated based training (SBT) such as virtual reality and other measures is an accepted and cost-effective way to reduce the chance of skill fade in certain clinical skills such as airway management.34 A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies (n=17) compared entry-level medical personnel learning airway techniques with either SBT or non- SBT. The authors found that the level of skill fade is consistent regardless of the type of device used to manage an airway. It can occur as early as four weeks after learning the skill and is even worse eight months later. There was no difference in this study between SBT and non-SBT methodology in the development or rate of skill fade.34 Further, studies using combinations of SBT, including augmented reality within a tactical environment, will help in determining the ideal training methodology.

One key study specifically investigated skill fade in non-medically trained soldiers using SADs. This study, which directly relates to the military context, compares different approaches to teaching the use of SADs within the German military to all soldiers.35 The authors evaluated which teaching method would involve the best skill retention, as it needed to be taught quickly to a large number of personnel. The group of non-medically trained soldiers (n=285) were randomly allocated to one of three groups, each testing a different style of instruction. One was a theory lecture, one a practical demonstration and the third was an instructional video. The authors measured both time to insert (had to be under 60 seconds) and accuracy determined by an assessor blinded to the method of instruction. To measure the level of skill fade, participants were retested three months later with only one day’s notice before the test. Two different airway devices were also tested. The greatest accuracy immediate post- instruction was achieved by the group, which had practice instruction at a combined success rate of 94%. The lecture and video groups were 68% and 74% respectively. The practical group also achieved a faster insertion rate at of 28.1 seconds (=/-19.6) seconds compared to between 43.2–49.2 seconds for the other methods. By the three-month retest stage, all groups had significantly dropped their accuracy, with the practical group dropping to 66% accuracy (p<0.001), and all groups had a significantly longer insertion time. The only exception was that the video group had a shorter insertion time when using the laryngeal mask, which is a type of supraglottic airway device (p=0.002). These authors concluded that no single method would reduce the skill fade and that a combination of both theoretical with practical followed up by video instruction has improved long-term outcomes.35 This study would be ideal to replicate within a domestic NZDF context.

Discussion

Despite the well-recognised concept of skill fade and the impact it has on personnel performing emergency airway management, both within a hospital, military deployed and domestic context, none of the literature reviewed has identified an ideal training interval. While in most cases, mandatory skill updates are in the region of one to two years, studies have identified that skill fade of practical skills can occur in as short a time frame of four weeks post-learning or practising the skills, with peak skill fade starting from six months post-skill and then continuing to decline. Theoretical skill fade can take longer to eventuate but still occurs, especially when recalling complex detail such as pharmacology use and calculations. An austere environment or the lack of opportunity to use these skills in a real-life setting adds another layer of complexity in finding the optimal training interval within a military context. With the rapid speed of virtual reality being incorporated into various types of medical simulation, there is still no definitive answer as to what is the best method and what the optimal training interval between practice would be for a skill such as emergency airway insertion as no single method of instruction protects against skill fade. Those studies that compared different types of instruction found a combined mix of practical and theory offered the best results. Most studies measured both accuracy of insertion as well as speed of insertion with an acceptable period of 20 seconds to a maximum of 60 seconds. Finally, care needs to be taken to ensure written content matches practical instruction.

Recommendations

This review has provided the background literature exploring the topic of skill fade in military medical care as it relates to airway management. Of note, no studies relating to skill fade could be sourced that explored the NZDF medic training context or other prehospital emergency care. Due to the range of approaches and limited number of studies in this area, it is clear that further research is needed to determine both the level of skill fade in emergency airway management in the military medic environment and the optimal training interval for relatively new skills such as supraglottic airway insertion.

Study limitations

The author’s lack of access to classified training data or literature as well as foreign language articles may have limited exposure to other potential studies or information. However, through the extensive search, nothing was apparent that warranted further cost or other means of retrieval. In addition, while there is potential for author bias, as the literature was not cross-examined by another reviewer for accuracy or acceptability topic, this has been mitigated as far as possible through cross-checking of sources.

Corresponding Author: W Maddocks, wendy.maddocks@canterbury.ac.nz

Authors: W Maddocks1

Author Affiliations:

1 Canterbury University, School of Health Sciences