Abstract

Purpose: To evaluate military personnel’s self-rated perceptions of their knowledge, experience and training after high-fidelity battle injury simulation.

Design: 26 military medical personnel participated in this quantitative study. Data was collected using a questionnaire after a six-day exercise where participants self-rated 10 statements regarding having sufficient medical, practical and ethical knowledge, experience and training. Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted to obtain the results.

Results: Nurses rated themselves statistically significantly higher than medics in having sufficient medical knowledge and experience, practical knowledge, experience and training, as well as ethical knowledge and experience. The nurses also rated themselves statistically significantly higher than physicians in having practical knowledge, experience and training. Physicians’ self-rated perception was low regarding sufficient knowledge, experience and training in practical skills. Physicians, nurses and medics all reported low ratings for sufficient training in ethical issues.

Discussion: Military medical personnel are required to have the knowledge and skills to work autonomously in challenging and threatening environments. For personnel that seldom see battlefield-like injuries, a clinical placement in a country with a high frequency of battlefield-like injuries would be advisable. A comparison between subjective and objective assessments may identify deficiencies in competence, which can negatively impact quality of care.

Keywords Emergency care, ethics, questionnaire, physician, nurse, medic

Introduction

Simulation in the Swedish Armed Forces Learning through simulation can contribute to the development of theoretical and practical knowledge for both civil and military healthcare professionals.1,2 Experience from simulations prepares medical personnel for handling similar complex situations in the future.3 The practical knowledge acquisition that occurs in simulation is applied and integrated as practical skills.4 In health care, practical skills consist of complex and professionally performed care actions.5 In simulation, scenarios and events can be engineered based on the existing skill levels of medical personnel. From this, inexperienced medical personnel can learn basic skills and experienced medical personnel can adjust, improve and consolidate prior skills.6

Learning through simulation takes place in an environment controlled by a facilitator. The environment can be free from the normal stimuli that are often found in real-life situations. By allowing the environment to affect the simulation, the learning situation can be strengthened and enable medical personnel to link their learning to a specific environment or situation.7,8 Power et al.9 have previously described how simulation in the Irish Defence Forces was considered relevant and applicable to personnel in the service within and outside of the country borders. The use of simulation in Swedish military medical education can largely be linked to military activities, as learning takes place in military locations. The training can take place in a field hospital or in a simulated hostile, unpredictable and challenging combat environment. This contributes to a more lifelike situation related to the shifting military prehospital-care work environment.

Medical personnel in the Swedish Armed Forces

The Swedish Armed Forces (SwAF) primarily focuses on the United Nations’ international peacekeeping and humanitarian missions. Swedish military medical personnel are employed either full-time or part-time as reserves. The education levels of the SwAF medical personnel are medics with a medical education within the armed forces. The medics have a 14-month theoretical and practical education, followed by clinical placement at civilian hospitals and in the ambulance service. Registered nurses have a basic three-year bachelor’s degree, followed by one year of clinical practice and subsequent specialisation in the form of a one-year master’s degree in, for example, prehospital care, anaesthesia or intensive care. The physicians have a basic fiveand-a-half-years of medical school, two years of internship and a five-year specialisation practice in, for example, surgery, anaesthesiology or emergency medicine.

All medical personnel are prepared for military medical care through specific military medical courses, including face-to-face lectures, practical training sessions and patient simulations. All education aims at creating a capable workforce; able to undertake their military duties wherever they will be sent. The SwAF provide medical care to both military personnel and to civilians. This care may include adults as well as children.

Medical knowledge, practical skills and ethical foundation in the Swedish Armed Forces

All military medical personnel are required to have the medical knowledge and practical skills to work autonomously, often in a challenging environment, unlike other healthcare settings.10 In twentiethcentury warfare, haemorrhage is the main cause of mortality,11 which, in the field, can often be difficult to detect due to the coverage of body armour.12 Body parts, such as the lower extremities, pelvis and face, are without protection and therefore, more exposed to gunshot wounds and injuries from explosive devices. Thoracic injuries caused by blasts are also related to a high incidence of morbidity and mortality.11,13 In trauma care, the potential to prevent deaths is increased. Malekpour et al.14 show how trauma education with a focus on assessment, resuscitation of patients and management of life-threatening injuries is associated with reduced mortality.

All medical personnel, both military and civilian, share the same ethical foundation in the care of patients. Military medical personnel are trained to perform according to professional moral values.15 Moral skills are the will and ability to identify situations where the medical personnel’s or patient’s dignity is at stake; to act in an ethical way and be able to take responsibility for themselves and others.16 Promoting moral skills helps soldiers manage ethical dilemmas responsibly.17 When the patient loses control of their injured body and encounters a frightening, unfamiliar emergency situation, the medical personnel become responsible for the patient’s survival.18 For all personnel in emergency care, it is vital not to compromise the patient’s dignity when survival is the focus and forget the individual behind the injury.19 The care of severely injured patients requires broad, but profound expertise for medical personnel. The military medical personnel require quality medical knowledge and practical skills, as well as a solid ethical foundation. This increases the need for training and feedback after caring for trauma patients.

The aim of this study was to evaluate military personnel’s self-rated perceptions of their knowledge, experience and training after high-fidelity battle injury simulation.

Method

Quantitative data was collected through participants’ written evaluation of 10 statements regarding having sufficient knowledge, experience and training of medical, practical and ethical issues, including one statement concerning feedback. Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted.

Participants

Participants in this study consisted of 26 military medical personnel – 20 males and 6 females – all stationed at a military field hospital. Professions included physicians (n=5, 5 males), nurses (n=11, 7 males, 4 females) and medics (n=10, 8 males, 2 females). The ages ranged from 21 to 51 years (mean 34). The experience from emergency care ranged from 1 to 15 years (mean 4). Inclusion criteria were military medical personnel participating in a six-day long SwAF military exercise, including high-fidelity trauma simulation in a military hospital setting. All participants had previous experience of simulation training.

Data collection

The participants served at the military hospital for 12-hour shifts, one shift per day, during the six-day exercise. Battlefield-trauma patients were constantly being transported from the prehospital setting to the military hospital. Patients were ground transported in Sisus, armoured personnel carriers configured to ambulances. They were also flown into the hospital with Blackhawk helicopters during all hours of the day. No actual patients were treated in the hospital during the exercise; therefore, all patients were simulated. The scenarios were made more immersive through the use of moulaged patients. In total, 60 patient scenarios were completed during the six-day exercise. Every participant partook in at least 30 patient scenarios as a member of the medical team including physicians, nurses and medics.

The simulated patient scenarios consisted of a wide range of typical battlefield injuries, for example, traumatic cardiac arrest, traumatic leg amputation, shrapnel injury to lower extremities and groin, injury to shoulders, lung and throat, and blast injuries from explosive devices. There was also a constant minor flow of non-battle patients. These patients presented with minor surgical injuries, cardiovascular disease, gynaecological problems and various gastrointestinal disorders. All moulage patients were educated and trained on symptoms and signs of their specific injury or disease. When a patient suffered from, for example, a cardiac arrest or an emergency tracheotomy had to be carried out, all medical personnel switched without interruption from the patient to a manikin lying on an adjacent patient bed.

Patients requiring a higher level of care were air transported with a TP-84 Hercules to a university hospital. Patients who died were initially cared for by the personnel at the hospital and then transported. Patient outcome aim was equal to a normal military care-giving situation. Deceased patients and patients discharged from the hospitals were again moulaged and sent back as new patients.

Ethical issues were incorporated into the patient scenarios, such as dealing with dying and dead patients from different cultural backgrounds. Feedback sessions were held as informal discussions in the team, including the researcher as facilitator after the simulated scenario had ended and before the next scenario started. The feedback aimed to support the learning experience.

At the end of the six-day exercise, participants were asked to rate 10 statements on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree and strongly disagree. The statements were aimed at responding to the participants’ self-rated perceptions of having sufficient knowledge, experience and training in medicine, practical skills and ethics in the care of battlefield-trauma patients. The statements were:

- I have sufficient medical knowledge to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient medical experience to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient medical training to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient practical skills knowledge to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient practical skills experience to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient practical skills training to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient ethical knowledge to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient ethical experience to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have sufficient ethical training to perform battlefield trauma care on a patient.

- I have the opportunity to receive feedback after caring for real trauma patients in order to improve my knowledge, practical skills and ethical knowledge, experience and training after caring for trauma patients.

Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 24.0. Descriptive analysis (central tendency and distribution) was used to describe the data, whereas inferential statistics (z-test, post-hoc Tukey) compared potential differences in variables between groups. The level of significance used was set at α=0.05.

Ethical consideration

The study followed the ethical principles in accordance with the World Medical Association20 regarding anonymity and integrity. Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Armed Forces Centre for Defence Medicine. All participants received oral information about the study and participated on a voluntary basis. All participants who were asked to participate accepted.

Results

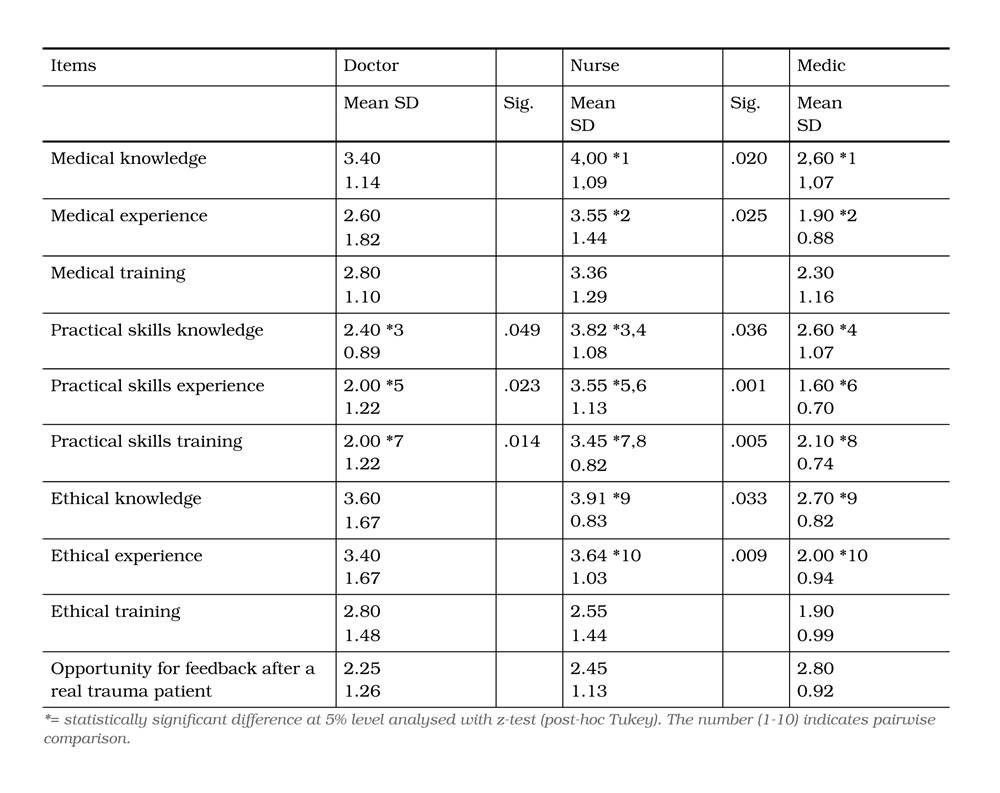

The results of the study are summarised in Table 1 as self-rated perceptions regarding having sufficient knowledge, experience and training in medical/practical skills/ethical aspects. A five-point Likert scale was used, where the score 1 indicates strongly disagree and the score 5 indicates strongly agree. Regarding the participants’ self-rated perceptions on the 5-point Likert scale, Table 1 shows 10 statistically significant differences between the nurses group and the physicians and medics. There was no statistically significant difference between the physicians and medics.

Of the 10 statements, nurses self-rated their sufficiency highest on eight statements, while doctors and medics self-rated their sufficiency highest on one statement each. The medics self-rated their sufficiency lowest on seven statements.

Table 1: Participants’ self-rated perception on the 5-point Likert scale (mean, SD) regarding having sufficient medical/practical/ethical aspects of knowledge, experience and training, including the opportunity to receive feedback after caring for a real trauma patient.

Medical knowledge/experience/training

There was a statistically significant difference between nurses and medics regarding self- rating of having sufficient medical knowledge, where the medics self-rated lower. Physicians also self-rated lower in comparison to nurses regarding sufficient medical knowledge, medical experience and medical training.

Practical skills knowledge/experience/training

There were also statistically significant differences between the group of nurses and the groups of physicians and medics in the practical skills statements regarding having sufficient knowledge, experience and training. For the statement regarding practical skills, nurses self-rated sufficiency relatively high compared to other statements, while both doctors and medics self-rated this statement as one of the lowest in their own groups.

Ethical knowledge/experience/training

Self-rating of sufficient ethical knowledge and ethical experience differed significantly between nurses and medics, where the medics answers rated lower on both statements. For having sufficient ethical knowledge, doctors self-rated themselves high compared to other statements, while nurses and medics self-rated this statement among the highest within their groups. Regarding having sufficient ethical training, the groups of nurses and medics self-rated themselves relatively low.

Opportunity to receive feedback

Medics self-rated the feedback statement highest of all three groups, whereas physicians rated the same statement lowest. This indicates that physicians feel they have fewer opportunities for feedback after caring for a trauma patient than nurses or medics (Table 1).

Discussion

Previous research has shown how the link between theoretical education and practical training needs to be strengthened to improve military medical education in the Nordic countries.21 Through simulations, the necessary knowledge and skills can be taught to deal with new, sometimes dangerous and complex or unexpected situations.22 Both physicians and nurses rated themselves high on sufficient medical knowledge. Holmberg et al.24 argue that care requires both general and specific knowledge, but that medical personnel can have knowledge without having immediate experience of it. Medical knowledge of care for critically ill or injured patients is classified as essential23 and can be obtained via simulation.24 Solid medical knowledge and experience can be a way to protect oneself against stressors leading to mental health problems common among military medical personnel caused by caring for severe polytrauma casualties.25

Conversely, all three professions ranked low on having sufficient medical training. This shows that the simulation of, for example, patients exposed to trauma needs to be introduced early in military healthcare training. Furthermore, there is a need for continuous simulation of these patient cases. This contributes to acquiring experience of military medical care.21 A study by Jen Heng et al.24 found that the participants ranked the opportunity for development of a single simulation as 4.42 on a 5-degree Likert scale, indicating the value of simulation. Good medical training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and airway management appear to be important areas for physicians and nurses in emergency care.23,24 Finnegan et al.10 believe that clinical placement in civilian hospitals during the person’s training needs to be supplied in areas with patients presenting similar injury patterns to those in military emergency care. Clinical placements should also include other areas, such as pain management, elective surgery, medical assessment units, paediatrics, burn units and plastic surgery.10

For sufficient practical skills knowledge, experience and training, the physicians rated themselves low. In the Nordic countries, there is a limited number of trauma cases per country and per year, which results in limited training opportunities for physicians. According to Grimm and Johnson,26 appropriate courses may provide training in skills needed in the care of trauma patients. Practical skills can be enhanced by simulation in the care of both critically ill and injured patients.24 Sonesson et al.21 suggest that the need to develop knowledge and skills in advanced military traumatology can be met by international cooperation with NATO and through e-learning.

In comparison, the nurses rated themselves highly on having sufficient practical skills knowledge. This can be explained by the fact that theoretical and practical action are often combined in nursing care. For the better part of the year, the military nurses who are reserves in SwAF work as specialists in their specific care area at a civilian hospital. Thus, nurses come in somewhat regular contact with the injuries they may face during military service.10 The nurses’ experience-based knowledge and skills, therefore, lead to an autonomous, responsible care staff.27 Aitkin et al.28 also believe that, in addition to experience, health and preventive hospital deaths are reduced through nurses’ high level of education (bachelor’s degree). According to Daouk-Öyry et al.,29 the competencies needed in an emergency medicine environment include professionalism and some sort of emotional intelligence. It is a unique situation when medical personnel meet a patient face to face in a critical life or death situation.30

Traditionally, military medical education and training consists of short theoretical briefings and practical training sessions for a limited time and often in extreme environments.21 This may be the reason why all professions rated themselves so low on having sufficient ethical training. It is problematic that they rated low in this category, as caring acts need to be incorporated through head, heart and hand to be accomplished.31 The care act needs to be included in the patient-caregiver relationship32 not just as a mechanical act without emotional association.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that no baseline was used to show improvement by the simulation. Another limitation is that no patients were children. Caring for children affected by traumatic injury requires specific competence.33 Previous research has shown that both physicians and nurses experience a shortage of theoretical and practical knowledge concerning paediatric emergencies, resulting in perceived negative stress.34,35 One additional limitation was that personnel were never forced to prioritise among patients, since the patient flow allowed all patients to receive optimal health care, regardless of injury or illness. Another limitation was that – since this is a subjective self-assessment – the participants could only rate specific statements. There might have been other statements that could have provided a better understanding of the situation.

Conclusion

All professions self-rated relatively low on all statements in this study regarding sufficient medical, practical and ethical knowledge, experience and training. The low rating is to be put in relation to a profession that requires medical personnel to have the knowledge and skills to work autonomously in challenging and potentially threatening environments. To regularly let personnel train in countries with a high frequency of battlefield-like injuries could be better than an extended clinical placement in a country with low frequency of battlefield-like injuries. This study’s subjective assessment in comparison with an objective assessment has the potential to identify deficiencies in levels of knowledge and skills, which can negatively impact the quality of care.