Introduction

August 2000 is the centenary of Australia’s involvement in the Boxer Rebellion. This was only the second and last time that the colonial naval forces saw overseas service, the first being the deployment to New Zealand by the Victorian screw sloop Victoria in 1860-1. The Boxer Rebellion was the larger deployment of the two, with over 600 men from NSW, Victoria and South Australia.

Although largely forgotten, the Boxer deployment was an important step in the formation of the Royal Australian Navy in 1911. It was used by the South Australian contingent commander (and founder of the RAN) Captain William Creswell, to convince British imperial and naval authorities that Australians could train, maintain and sustain an efficient navy of their own.

Each contingent had its own medical personnel and the aim of this two-part article is to tell their story. The first covers the SA contingent and their ship HMCS Protector, while the second covers the NSW and Victorian contingents.

Background

Until the 1840’s the Western powers only traded with China on a seasonal basis via ‘factories’ in Canton. Although at first Chinese goods were paid for in bullion, corrupt officials later allowed the Europeans to sell opium. After Chinese attempts to reassert control instigated the 1842 Opium War, the ensuing British victory lead to large indemnities, permission to trade from other ports beside Canton, the right to year-round residency and the establishment of Hong Kong.

Further conflict became inevitable as British merchants extended their demands, especially after the 1860 China War resulted in a charter for all missionaries. Chinese peasants were hostile to missionaries and their converts because of their demands for land to build churches and housing. They also believed the ‘foreign devils’ buried Chinese babies in the foundations of important buildings. Further- more, although there were only three short railways in China by 1900, many more were being built. The peasants believed railway engines to be fire-breathing dragons and the work of devils. The railway builder’s neglect of feng shui (not to mention ancestral graves and other sacred sites) did little to help matters.

Secret societies have always been part of Chinese daily life. The name I He Tuan (“Righteous Harmony Group”). was corrupted by Westerners to I He Chuan (“Righteous Harmony Fists”)- hence “Boxers’. Their aim was to kill all foreigners in China. Although lacking a specific leader, the Boxers shared the inculcation of invulnerability to foreign weapons, the battle cry ‘Sha! Sha!” (“Kill! Kill!”). the use of red shirts as a type of uniform, and the use of complicated, prolonged and highly unpleasant tortures.

The Boxer rebellion began in late 1898, after the Germans plundered the provinces south and east of Peking, with attacks on Chinese Christians, including arson, torture and murder. These intensified in early 1900 and by

28 May the beleaguered legations at Peking sought military assistance from the international naval forces at Taku. Further reinforcements were beaten back , initiating a siege of the legations, which lasted two months. Further reinforcements were sought overseas, but most of the fighting was over by the time the Australians arrived.

Australian Responses

In Australia all eyes was on the Boer War and the impending Federation of the six colonies. These received a request for assistance from British Secretary of State Joseph Chamberlain on 28June. The Royal Navy in Australia.

The Royal Navy gunboats HMS Mohawk (with Staff Surgeon John Moore) and Lizard (Surgeon! Sydney Croneen) with the third-class cruiser HMS Wallaroo (Surgeon Frank Bradshaw) departed Sydney on 2 July. As part of the Auxiliary Squadron, Wallaroo required colonial approval to release her in accordance with the 1888 Naval Agreement.2

All three ships were manned by RN blue- jackets with their own sickbay staff. Moore had qualified in Ireland in 1884, Croneen in London in 1895, and Bradshaw in Ireland in 1889.2 Midshipman A.L. Fletcher left his impressions of the RN medical branch at the time:

‘The surgeons were about 75 per cent ex- Trinity College, Dublin, 20 per cent Scottish universities and the odd 5 per cent English. Perfect dears but very thirsty when young. Their medicine may have been crude, but they knew a lot about malaria and VD. My chief memories of the sick bay were No 9 pills, almost atomic in action, for internal disorders, santonin for worms – very prevalent in the East – and vats of zinc ointment for everything else.’3

Colonial Responses.

The colonial response was characterised by attempts to outdo each other. On 29 June the Victorians offered their gunboat Albert, but later decided to send 200 sailors for service ashore. The following day Queensland offered either of their two gunboats Gayundah or Paluma, using RN personnel. This was rejected as both ships were considered too old and slow, however South Australia’s offer of the gunboat Protector on 2 July was provisionally accepted three days later. Besides agreeing to Wallaroo’s release, the New South Wales govemment suggested its Naval Brigade be used as crews for other Auxiliary Squadron ships. The British instead accepted a contingent of 250 sailors for service ashore with the Victorians.

1 The rank of Staff Surgeon became Surgeon Lieutenant- Commander. and the rank of Surgeon became Surgeon Lieutenant in 1920.

In addition the RN ships of the Australia Squadron. the

1 888 Naval Agreement gave the colonies partial control of five small cruisers and two gunboats manned and operated by the RN, in exchange for a small colonial subsid y. Besides acting as a reserve the Auxiliary Squadron was intended to train Australians for naval service but this never happened. Although this arrangement was never satisfactory for either party it lasted until the Royal Australian Navy was established in 191 1. See Nichols. Bob. Statesmen and Sailors: Australian Nanil Defence 1870-1920. Standard Publishing House. Balmain. 1995.

The South Australian Contingent

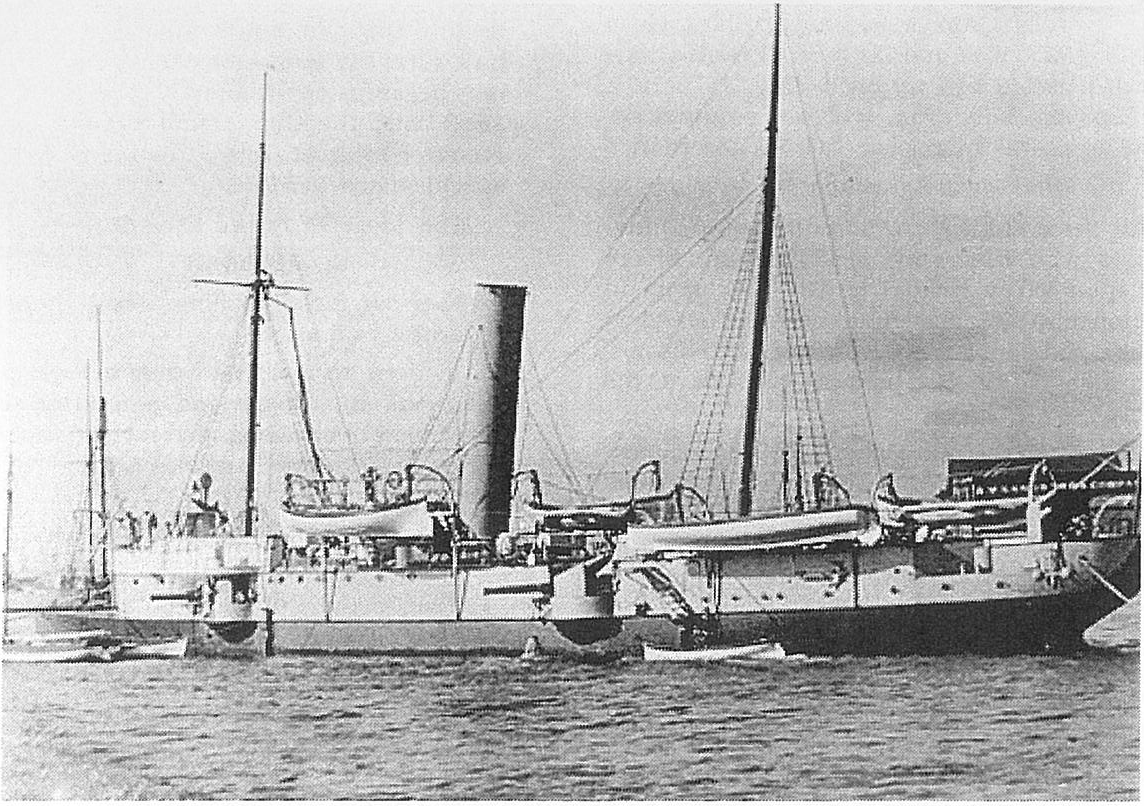

Her Majestv’s Colonial Ship (HMCS) Protector. In July 1882 the South Australian parliament had allocated funds for a gunboat. Construction began at Newcastle-on-Tyne in November 1882, with the ship commissioning as HMCS Protector in June 1884. Costing £65,000, her specifications were: 188′ long, 30′ beam, 12’6″ draft 960 tons displacement Two engines totalling 1640 horsepower giving 14.5 knots.

In modem terms these dimensions are less than half the length and a quarter the displacement of a RAN guided missile frigate. Protector was however very heavily armed for her size, with: One 12-ton eight-inch gun forward firing a 180-pound shell, Five 4-ton six-inch guns (two on each beam, one aft) firing an 80-pound shell, Four 3-pounder guns, and Five machine guns. Protector also had a 1″ armour belt four feet wide on the waterline, as well as a one inch thick steel conning tower, a shield one inch thick for the eight inch gun, and shields two inches thick for the six inch guns. She sailed for Adelaide in June 1884 under Captain J.C.P. Walcot, RN, who remained Commandant of the South Australian Naval Forces (SANF) until 1893. She arrived on 30 September 1884 after calling at Gibraltar, Malta, Suez, Colombo and Albany. One member with fever was landed at Colombo and an- other died before reaching Albany, despite the efforts of a Dr William Reid. Reid had signed on as Surgeon3 for the voyage only,4 in contrast to the rest of the crew who signed articles for the voyage out and for three years thereafter.

Lieutenant William Creswell joined Protector in October 1885 as First Lieutenant, after his predecessor was medically discharged for rheumatism and partial leg paralysis. Bom in 1852, Creswell entered the RN in 1865, but had been working as a jackaroo following his own medical discharge in 1879.6 Years later he wrote:

“… at Tientsin, Captain Jellicoe … said he wondered how they could have designed such a ship of such small tonnage to carry such an armament.

‘The Register. Adelaide. I October 1 884. Cited in South Australian State Archive Research Note 906 ‘A Warship for SA’.

That a ship, 15 years after her first commission, should elicit such praise from the very highest naval opinion of the day is proof in-deed that she was an exceptional and very remarkable vessel.

HMCS PROTECTOR, cl900

(818116, with permission Mortlock Library of SA)

“Some idea of the Protector’s power and great stride in advance made by her design and armament may be gathered from the fact that at that time we could, excepting in heavy weather, out-steam and always (by some two or three thousand yards) outrange the great flagship on the station, the Nelson, an armoured cruiser, many times the Protector’ s weight of metal and about six times her size!

It was a constant wonder to me in my early South Australian days that there was so little appreciation of the Protector’s real value and the complete defence she provided against the only danger to which we should be exposed in war.”7

Over the next 15 years Protector undertook various duties. In December 1885 she suffered a breech explosion during the Royal Salute for South Australia’s Proclamation Day. Able Seaman Phineas Davies was killed and an- other sailor was injured. Things went further awry when Davies was buried as a Catholic but tumed out to be Jewish.

Admiral Tryon, Commander-in -Chief of the Australia Station, inspected Protector the following year and stated privately that she “was not only better kept than any ship on the Station, but was so much better kept that there was no ground for comparison.”

Besides her wartime role, Protector was used for lifeboat training and rescue, after the Star of Greece was wrecked at Port Willunga with great loss of life in 1888. In 1890 she assisted Cathcart off Cape Jervis, rescued occupants of the Semaphore baths after the jetty was destroyed in a storm, and manned the Governor Musgrave to rescue survivors from the You Yangs, after the latter was wrecked on Kangaroo Island.4

The 1890 Depression hit the colonies hard and 1893 it was suggested that Protector be sold. Instead she was reduced to reserve with only 21 officers and men. Creswell took over from Walcot as SANF Commandant and made the best of a bad financial situation until he took over the Queensland Navy in April 1900.

China Deployment Preparations

All three contingents were dogged by the mis- match between RN and colonial pay rates (1s 9d per day for RN able seamen compared with 7s for South Australians). Although Protector was accepted on 5 July, it was not until 31 July that the British authorities agreed to a £1000 per month subsidy.1 She also needed 100 men, of which 90 had to come from the reserve. Recruiting went well once they were paid South Australian rates. They then signed the following oath on the enlistment form:

‘We agree to serve Her majesty the Queen on board HMCS PROTECTOR, or other War Vessel as May be directed, or on shore, in any part of the world, and for any period not exceeding one year, at the rate of pay against our names, and also agree whilst serving to be subject to the articles of war and queen’s Regulations for the time being in force in the Royal Navy.”10

Captain Chapman James Clare had only recently taken over from Creswell as SANF Commandant. On 5 July 1900 he had written to the Chief Secretary regarding clothing allowances, but a medical officer was not included on the initial list. Five days later Clare added:

“A doctor may also require an allowance for uniform when appointed. Will the Hon the Chief Secretary please approve this slight alteration if required.”10

An account with Shierlaw and Co ‘for Dr Morris’ has survived as follows:

| Altering mess dress to regulation, new lace etc |

£2- 1 0-0 |

| Frock suit, regulation , naval surgeon | £10-0-0 |

| Cap and badge, naval surgeon | £1 -1-0 |

| Sword | £7-0-0 |

| Sword belt | £1-10-0 |

| Total | £22-1-0 |

Received £14-13-0 on account 11 October 190010

Apart from belatedly getting his uniform allowance, it is interesting to speculate whether the prospect of a medical officer handling any sharp implement larger than a scalpel would have worried Protector’s gunnery officer any more than it does his professional descendants.

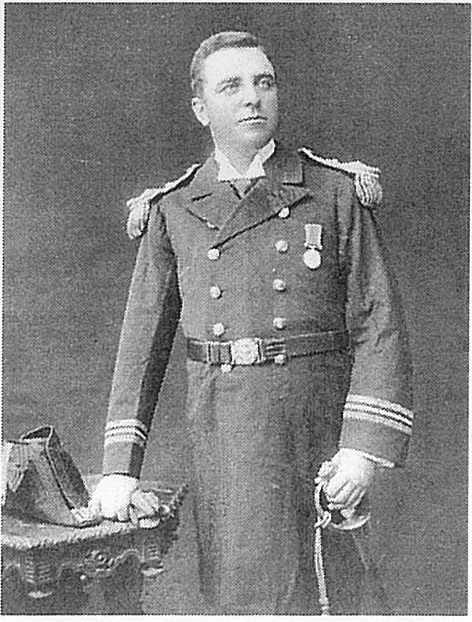

Staff Surgeon Bedlington Howel Morris

Dr Morris was not officially appointed into the SANF until 9 August.11 Not surprisingly, his name is last on the enlistment form. He was paid 21 shillings per day for 169 days service (6 August 1900 to 13 January 1901). receiving £169 1s Od after deductions. By comparison Creswell was paid 22 shillings and sixpence per day with the other officers paid substantially less.l2 It is interesting that Morris was appointed over17 medical officers in the South Australian Military Forces, four of whom were in South Africa.2 As Creswell used Protector to further his aim of an Australian navy, it is likely he was keen to remain independent of any army support. He seemed satisfied with

Staff Surgeon B.H. Morris, 1901

(86401, with permission Mortlock Library of SA)

Morris, as he later wrote:

“…Surgeon Morris, to whom the success of the expedition owed much, quite the ideal man for the work under such temporary conditions, and earned the confidence and regard of all on board.”7

Morris certainly did not need the job, having already made his mark in South Australia. Born at Anglesea in North Wales on 22 April 1868, he was educated at Beaumaris and St Thomas’s College and graduated MBBS from Durham University in 1893 with first class honours. He was the Armstrong Scholar for medicine, the Goyder Scholar for surgery and had won first prize for surgery. Following residency at Durham County Hospital and the Denbighshire and Flintshire Infirmary and Dispensary, he was the transport medical offi cer for the Netherlands-India Service to Java and Malaya. Later he was surgeon to the Blue Funnel Company on its eastern routes. l3 It seems likely that he became familiar with maritime and tropical medicine during this time. He was appointed to the Adelaide Hos pital (now the Royal Adelaide Hospital) as Resident Assistant Surgeon in 13 November 189614 and received his South Australian registration (no 557) on 7 January 1897.15

He was then embroiled in the Adelaide Hospital Row, which influenced South Australian medical politics into the 1970’s. The ‘Row’

began with a trivial dispute over a nursing appointment but by July 1895 had become a violent ‘class war’ between the establishment- dominated hospital board and the government, lead by Federation Father Charles Cameron Kingston. The latter had horsewhipped a personal enemy in the middle of Adelaide and was once arrested in Victoria Square on his way to a duel with a loaded pistol. After the hospital board was sacked the members re- signed all their other posts, including their teaching positions at the University of Ade- laide. For some years thereafter this forced Adelaide students to complete their studies interstate or overseas. Meanwhile the Adelaide Hospital kept going under Drs Ramsay Smith and Leith Napier, who were denounced as medical ‘scabs’.IS

Even in his early career, Morris seems to have been an astute political operator, supporting Smith and Napier yet avoiding their vilification. Just prior to his appointment to the SANF, he had been appointed Government Medical Officer and Prisons Surgeon, Chief Medical Officer to the Destitute Poor Department and Chief Medical Officer to the State Children’s Department.’6

Other Preparations.

The next concern was Protector’s legal status, as she could legally operate as a warship only within South Australian territorial waters. This was resolved by commissioning the ship into the RN unit at Hong Kong and putting Captain Creswell (ex-RN) back in command with Clare as First Lieutenant.

Concerns regarding the ship herself were coal, water (with no condensers or evaporators her endurance was limited to l0 days at l 0 knots) and her ammunition which was not standardised with the RN. Meanwhile Shier- laws completed the crew kit up, each man receiving a cholera belt (a padded belt worn over the kidneys to prevent cholera, which remained in RN use until World War II).! Morris arrived in time to generate a bill for £7 13s 2d for medical stores from Fauldings before the ship left Adelaide on 6 August.IO

The Deployment

The first defaulters parade on 7 August had Able Seaman 2nd Class Russel Grant charged with leave breaking and being drunk. He claimed to have missed the boat while seeing a doctor and that the latter prescribed an excessive dose of brandy. This was not accepted and Grant received l 0 days punishment and stoppage of grog.’?

Protector arrived at Sydney on l 0 August and departed for Brisbane two days later,

during which Morris expended another £74 l 7s ld on medical stores from Elliot Brothers.IO In addition one sailor cut his foot on an illicit run ashore.l7 Creswell rejoined his old ship on 14 August and sailed next day for Townsville and Thursday Island, where one sailor became ill from heat stress but recovered.’7 She crossed the Line on 30 August, where the crew had the usual frivolities:

“Neptune with his wife & suite were there to receive each one. A guard was also formed with the police. Each one then had to go through the Ordinances. As your name was called out you would pass through the guard line on either side, & the “Doctorn was the first to inspect you, who would therefore prescribe for you accordingly. and a person who was known to be dilatory in regards to his cleanliness during the trip was given a thorough good overhaul by the doctor’s orders. One or two this class suffered the full penalty, & really they looked quite fresh & nice for three weeks after. The doctor and his assistant would also give you a .pill. which was not at all palatable, consisting chiefly of flour, mustard soap, tobacco, pepper, mixed with paint oil. I t was no use to protest against it because the easier you went the better you got off & while taking the pill in your mouth would be stuffed up with soft soap by an attendant standing behind you…”l7

Although it was likely (and one would certainly hope) that Neptune’s doctor and Morris were not in fact the same person, medical officers still participate in today’s somewhat attenuated line crossing ceremonies – albeit mostly on the receiving end.

Protector arrived for coal at Ilo-Ilo on Panay Island in the Philippines on 3 September and sailed two days later. After a horrendous voyage at the height of the typhoon season Protec- tor reached Hong Kong on 9 September. During the trip north, while the engineers endured temperatures of 124° F below deck, Creswell drilled his crew hard, including action stations, gunnery drills, fire stations, collision drills, and abandon ship. ‘Our Correspondent’ for the Herald (not identified) wrote:

“…the port watch were given an hour’s lecture on ‘First Aid’ by Doctor Morris, who is interesting, instructive and amusing at the same time. Imaginary limbs were bound up, arteries and veins stopped from bleeding, until some advanced pupils began to handle bandages and tourniquets as if they wished for a real subject on whom to show their efficiency.”‘

At least the intent. if at times perhaps not the skill, of naval first aid training has remained unchanged during the last 100 years.

On arrival on Hong Kong, Creswell smugly reported no illness, defects or need for coaling assistance, receiving a ‘very well done’ from the Port Admiral. On being invited to obtain stores, Creswell’s crew enthusiastically availed themselves of the opportunity to overcome several longstanding deficiencies. 1

Protector and her officers including Morris were commissioned into the RN on 11 September and sailed on 19 September, arriving the next day at Woosung and Shanghai. She finally arrived at the British naval base at Wei-Hai-Wei on 30 September, where Admiral Seymour (C-in-C China Station) interviewed Creswell. Years later the latter wrote:

‘Sir Edward Seymour plied me with questions, asked and noted many details and particulars of the ship.

“And how many sick do you have?’

“None sir, the fact is there’s nowhere to put them.”

I told him of our grueling trip to Hong Kong. “Well if you have no sick. I’m hanged if I see why anybody else should have any sick.”

I learned later that a battleship anxious for a run to Japan had submitted a big sick list in

support of her request.”l

Creswell’s comments suggests Morris did his part in ensuring Protector made a good im- pression during this visit, which proved crucial to the establishment of the RAN.

Protector’s only real chance of action came on arriving at Taku on 1 October, where she was to participate in attacks on the forts at Shan-hai-kwan and Ching-huang-tao. Unfortunately the first had already been captured and on parading the port watch of seamen to attack the second Creswell found the Russians had got in first. Instead, A boat party including Able Seaman George Jeffery spent a few days dragging for and removing mines laid at the approaches to Ching-huang-tao and surveying a site for a pier to land military stores. IS It is interesting to contrast these efforts with those of CDT Three in Kuwait 91 years later.

With no chance of action, Protector spent the rest of her time in China from 2 October to

6 November carrying dispatches, stores and personnel between Taku, Chan Huang Twa,

1 ‘Our First Australian Warship – Story of the Protector – Interesting R eminiscences by Admiral Sir William Creswell.• The Register. Adelaide. 26 June 1924 p10. Quoted in Nichols, Bob. Bluejackets and Boxers: Australia:Naval Expedition to The Boxer Uprising. Allen and Unwin. Sydney. 1 986.

Shan-hai-kwan and Wei-Hai-Wei. Captain Jellicoe (later commander of the British Grand Fleet at Jutland in 1916) wrote to Creswell complimenting Protector that she was “never sick or sorry, and always ready for a job of work.”2.s

On 2 November Protector was released to return home and she left Wei-Hai-Wei five days later. She arrived at Hong Kong on 15 November where her stores were re- turned/replenished and she underwent docking. Her crew participated at a church service at HMS Tamar on 18 November and she de- commissioned as a RN unit the same day. She sailed on 24 November via Manila, Ambon and Thursday Island, arriving at Brisbane on 14 December. She was cleaned by Gayundah’s crew and left for Sydney where she arrived on

18 December. Protector remained for celebrations marking the establishment of Common- wealth of Australia on 1 January 1901, sailing next day to arrive at Adelaide on 6 January (flying the new Australian national flag for the first time) where she paid off two days later, having travelled 16,000 miles.

The Adelaide Register included the following interview with Captain Clare on her return:

What has been the general impression concerning the men?

Throughout I may say the opinion ex- pressed has been complementary. It is interesting to know that ours was the most healthy ship on the station. While nearly every man-of- war had 15 to 20 percent sick, our sick-list was practically nil, with the exception of a few cases of influenza. With regard to the ship, she was certainly the most heavily armed vessel for her size on the China Station. Both Admiral Seymour (C-in-C China Station) and Admiral Pearson (C-in-C Australia Station) , who inspected me in Sydney, said she was an efficient ship.

You were disappointed in not going into action?

Yes, we were. The whole ship’s company would have embraced the opportunity had it arisen, but there was not the slightest prospect of it. It has, however, been a great experience. The Protector and her crew could take her place anywhere in the British navy, and it is to the credit of South Australia that she alone of the Australian States was in the position to send a boat like Protector upon active service. You may say that the relations be- tween the officers have been of the most cordial nature. No disputes of any sort have arisen.’3

Quoted in Jones. Colin. Australia n Colonial Nm•ies. Australian War Memorial, Canben•a. 1 986. p 127

Aftermath

Protector was transferred to the Common- wealth Naval Forces in March 1901 and to the RAN in 1911. During World War I she was used for minesweeping patrols off Port Phillip Bay. She was sold in 1924 and from 1931 was used as a cargo lighter until she was purchased by the Navy in July 1943 for the US Army. She left Sydney under tow on 6 September for New Guinea, but on 30 December the tow broke and she sustained heavy dam- age when she was hit by an Army tug. She was taken to Gladstone in a sinking condition and was sold for use as a breakwater on Heron Island.J 9 Protector’s relics include her steering wheel (now in the Maritime Head- quarters foyer) and one of her six inch guns at Semaphore in Adelaide.

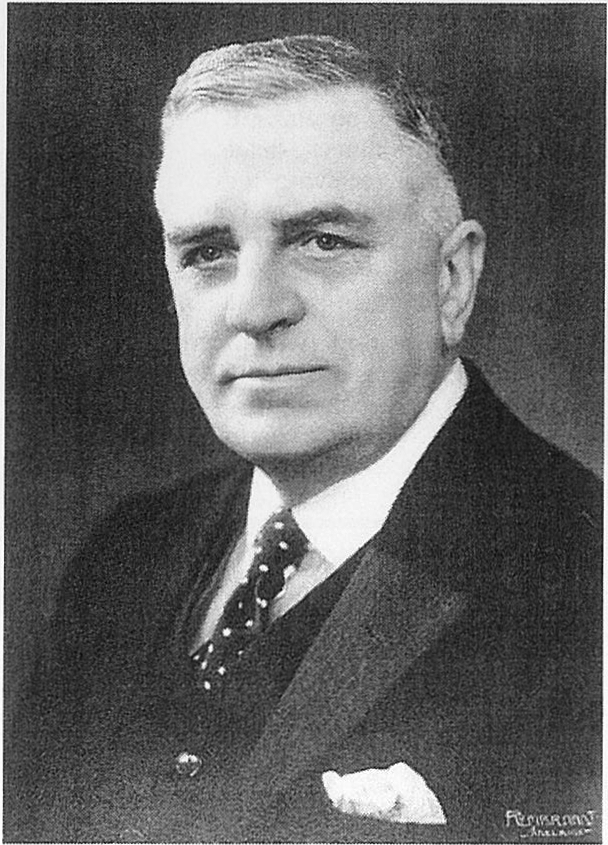

Bedlington Morris married Ada Jessica Shearer at St Luke’s Church, Whitmore Square in Adelaide on 11 August 190220 and they had one child Cledwyn Howe! Morris on

24 Nov 1903.21 In 1914 he became the South Australian Inspector General of Hospitals, by which he became Chairman of the Adelaide Hospital Board, the Nurses Registration Board , the Dental Association Board and the Mental Defectives Board . He was also a member of the Medical Board of South Australia, the Faculty of Medicine at Adelaide University and the Medical-Psychological Association of Great Britain and Ireland. Morris also established the Mareeba Babies Hospital and the Bedford Park Sanatorium. IS

He maintained his naval links and was promoted to Fleet Surgeon4 in the Royal Australian Naval Brigade (later renamed the RAN Reserve) on 2 July 1910.22 Having failed to get away again during World War I , he retired from the RANR on 1 February 1924. He died on 10 July 1936 and was cremated the following day at West Terrace Cemetery. In December 1936 the Northfield Consumptive Hospital was renamed the Morris Hospital (now the Hampstead Rehabilitation Unit of the Royal Adelaide Hospital).23

Dr B.H. Morris as SA Inspector General of Hospitals (GRG 78/96/8, SA State Archive )

Conclusion

As they entered the new century, the Australian naval forces consisted of small numbers of reservists manning small and obsolete ships (when they had them). Protector’s China deployment showed what Australian seamen were capable of, given the opportunity. It was up to Creswell to ensure that that opportunity was not wasted . Feedback while in China and subsequent events suggests that he had considerable success.

Besides adding credence to Creswell’s aim of an Australian Navy, it seems striking how many things have remained unchanged over the last 100 years. Creswell’s work-up of his crew bears strong similarities with OLOC preparations for the DAMASK deployments. AB Jeffery’s mine clearing efforts appears to parallel CDT Three’s work in Kuwait. Certainly most DAMASK veterans will readily identify with Creswell’s crew being worked up for action , but instead performing tedious but essential operational tasks, in a foreign environment far from home.

In this Protector’s medical department, personified by Staff Surgeon Morris, did its part in preventing illness while preparing to treat casualties. Although no medical journal ap-pears to have survived, his favourably reported first aid training and relative lack of illness on board suggests his efforts were highly successful. lt seems noteworthy that l00 years ago the requirement for medical support, by a practitioner experienced in maritime environ- mental issues, was recognised and accepted. The fact that it came late in deployment planning, resulting in a rush to get ready for sea before the ship sailed, remains a consistent theme. One would hope that this aspect of na val operations will improve during the next 100 years!