Purpose

More than a century after its establishment, many Royal Australian Navy (RAN) uniforms and ranks still reflect those used by the (British) Royal Navy (RN). Previous articles have described the history of Navy sailor uniforms or ‘rigs’ since 1509,1 the development of male and female health sailor uniforms since 1879,2 and the evolution of their rank and rate badges since 1827.3

The purpose of this two-part article is to describe the development of Australian Navy health officer uniforms. This part describes the overall development of male and female RN, Australian colonial and RAN uniforms and ranks since the 11th century. The second will focus on RN and RAN medical, dental, medical administration and nursing officer uniforms.

Background

A previous article described how English maritime power during the five centuries after the 1066 Norman conquest was mostly limited to the North Sea and English Channel. During this time, the monarch hired his ships out to the merchants for trade, and could ‘arrest’ their ships and crews for his own purposes when required. The same ships were therefore used for both warlike and peacetime purposes.

During this time, mariners performed their duties in accordance with the Laws (also Rules or Rolls) of Oléron4 and the Black Book of the Admiralty,5 which applied to all English ships irrespective of who owned them. Consequently, English mariners were employed interchangeably between private merchants and their monarch until the 1850s.6

The same ‘master’ likewise held shipboard ‘command’ in both peace and war. Masters began their seagoing life as apprentices, when the absence of manuals or charts meant that their navigation and seamanship skills were totally dependent on memory.7 Furthermore, the Laws of Oléron, and the common social background of masters and their crews, meant that their leadership style had to be one of ‘first among equals’; for example, masters were required to seek agreement from their crews as to when their ship was ready to sail.8

As ships became larger, they were able to keep the sea longer, and to voyage further. This required increasingly specialised crewmembers such as the boatswain, carpenter and cook. In the King’s ships, these specialists were later joined by the gunner, purser and, eventually, the surgeon. Apart from the cook—whose job, in fact, did not require any culinary expertise—like the master, the professional development for these specialists were all based on long apprenticeships.

Hence, there was no formal seagoing ‘officer class’ as understood today, until mathematically-based navigation methods from the mid-16th century required masters to have greater literacy skills, as likewise did their subordinates regarding their own functions and roles.

During the medieval period, fighting at sea entailed grappling and boarding, followed by hand-to-hand combat. Although the prevalence of piracy meant that, sailors often had to defend themselves even in peacetime, soldiers were carried on the rare occasions that entailed wartime sea fighting.9 As military command ashore was the prerogative of the English aristocracy (per their feudal obligations to their monarch), the lower standing of what became known as ‘tarpaulin’ officers usually, but not always, made them subordinate to the ‘gentlemen’ officers who commanded the soldiers when embarked.

These ‘gentlemen’ officers continued to exercise command, even after specialised warships with below-deck large-calibre gun firing through gunports eventually eliminated their soldiers from the early 16th century.10 Over time, their literacy skills enabled them to acquire comparable navigation and seamanship skills—if not necessarily the same experience—as ‘tarpaulin’ masters. While the term ‘master’ technically remains extant for merchant ship captains, the introduction of a formal seamanship examination of ‘gentlemen’ officers for promotion to lieutenant from 1678,11 eventually made masters obsolete within Navy by the end of the 19th century.12

Hence, Navy had two types of officer at the beginning of the 16th century: ‘gentlemen’ officers received ‘commissions’ from the monarch to exercise command on his or her behalf, while ‘tarpaulin’ officers received ‘warrants’ from the relevant Navy Board.13

The first commissioned ranks were lieutenant, captain and admiral. The title ‘Admiral’ was first used by the English to describe a fleet commander in 1297.14 Full Admirals usually led their fleet from the centre, while Vice Admirals were secondsin-command who led the van or front, and Rear Admirals were thirds-in-command who led the rear. The first Admiral of the Fleet, ranked above all of these admirals, was appointed in 1688.15

The title ‘Commodore’ has existed since 1690, but was not formalised until the 1980s. It initially referred to senior captains appointed to command fleets or squadrons, where an admiral was not required or was unavailable.16

The title ‘Captain’ was first used for the ship’s commanding officer above the master in 1380,17 while ‘Master and Commander’ (‘Commander’ from 1794), did likewise for smaller ships from the 1690s. ‘Lieutenant’ has been used since Elizabethan times for ‘gentlemen’ officers who exercised command over the master on the captain’s behalf. ‘Sub Lieutenants’ were introduced in 1861, while ‘Midshipman’ has referred to prospective commissioned officers since the 17th century.18

Meanwhile, Navy warrant officers themselves came in two forms. The ‘standing’ warrant officers—boatswains, gunners, carpenters, pursers and cooks—stood by their ships even when they were not in service, while masters, chaplains and surgeons were only appointed for ships in service as required.19

Some warrant officers eventually achieved commissioned status (surgeons from 1843),20 while the remainder were abolished in 1949.21 Commissioned and warrant officers were both divided between ‘military’ and ‘civil’ branches—with health officers included with the latter—until 1957.22

Hence, the current Warrant Officer title used for the RAN’s senior sailor rank above Chief Petty Officer since 1971, is completely unrelated to its original use for over 400 years from the early 16th century, for highly experienced and skilled yet patently subordinate non-sailor officers, who were often employed interchangeably between the King’s ships and civilian merchantmen.

Male RN officer uniforms

Although the French and Spanish navies introduced officer uniforms in the early 18th century, the RN did not do so until 1748. The lack of uniform was felt to reduce social, military and/or diplomatic standing with foreigners, while creating difficulty proving one’s rank if captured. The main issue however, was the inability to clearly indicate status within Navy, which for example meant that the captain of a first rate had little to distinguish him from that of a sloop (especially if the latter was well heeled).23

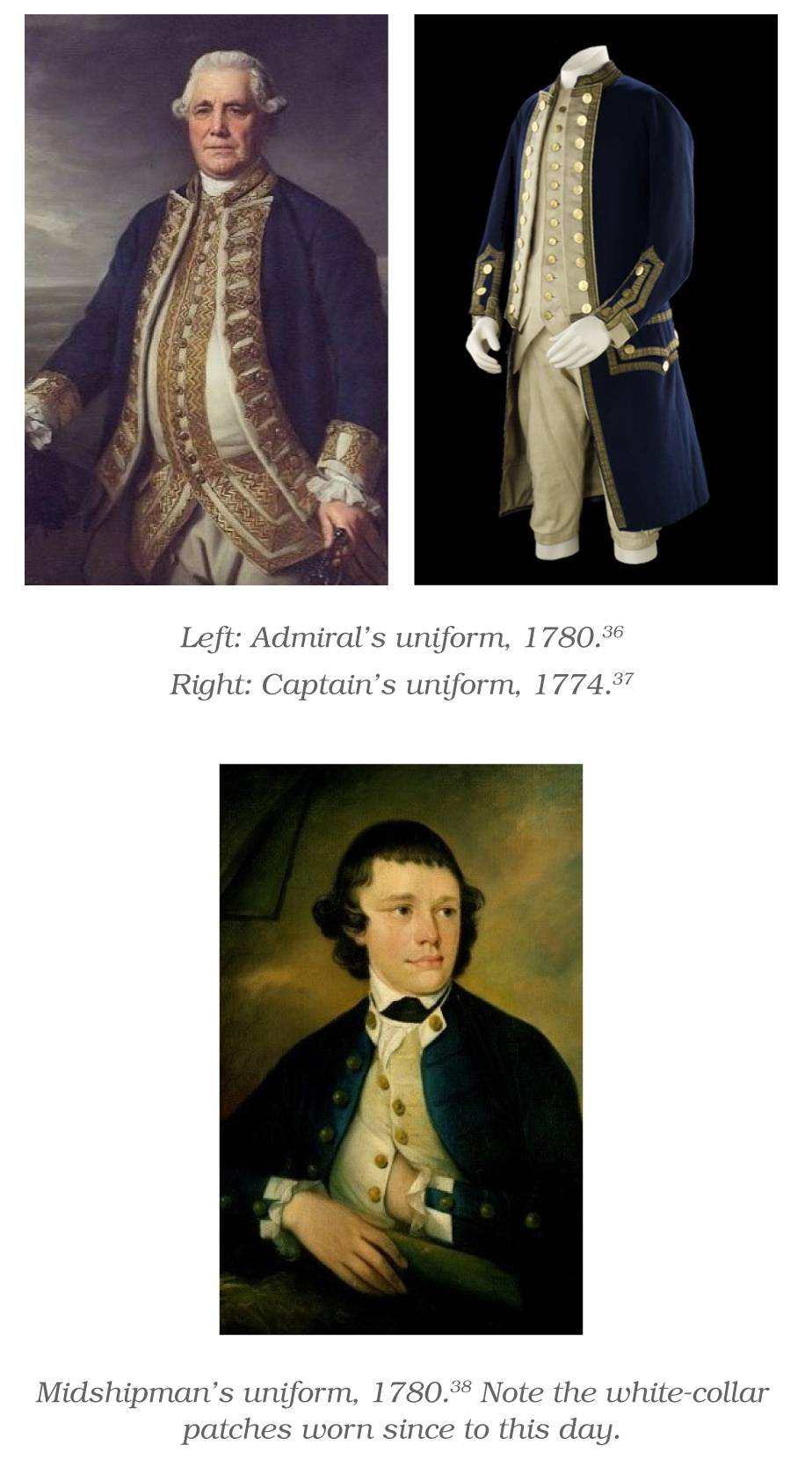

The first uniforms were for commissioned officers and midshipmen. Unlike today, where rank is indicated by adornments to a single standard uniform, each rank had its own unique attire. Midshipmen excepted, these included a ‘dress’ uniform for formal occasions, and an ‘undress’ uniform for daily wear. Anecdotally, the blue and white colours were chosen by King George II, based on a horse riding habit worn by the Duchess of Bedford.24 Officer uniform styles have since generally followed contemporary civilian fashion.

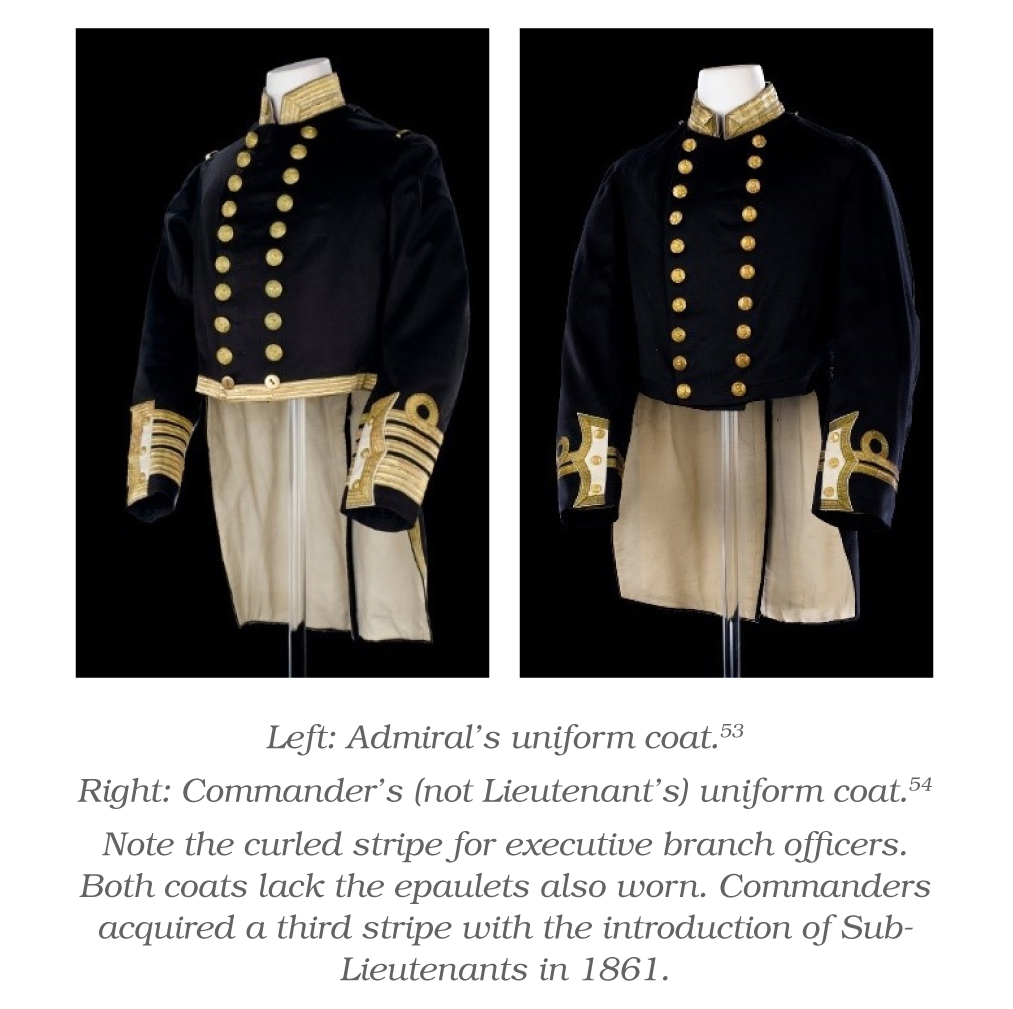

The use of sleeve stripes to identify rank did not occur until 1856. Lieutenants initially had one stripe, commanders two, and captains three, until the introduction of the Sub Lieutenant rank in 1861 resulted in each gaining an extra stripe. Lieutenants with over eight years’ seniority wore a half-stripe from 1877, which became the formal Lieutenant Commander rank from 1914.25

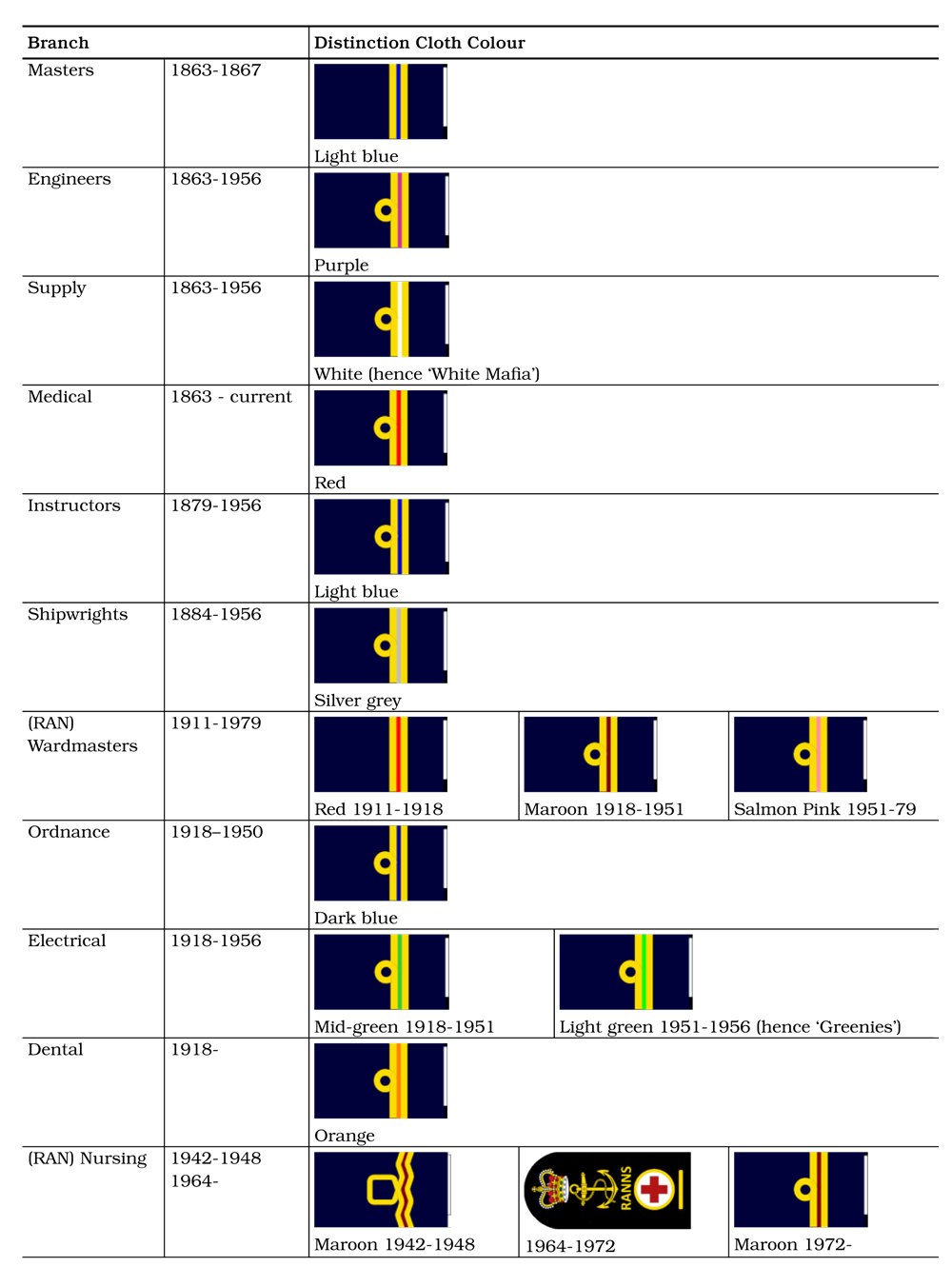

The ‘executive curl’ on the proximal stripe was initially only worn by ‘military’ executive seamen branch officers, in order to distinguish them from non-executive ‘military’ and ‘civil’ branch officers. ‘Distinction cloths’, per Table 1, were added between the stripes for the latter officers from 1863 until their abolition in 1956, except for medical, dental and wardmaster (later medical administration) officers.

A tropical uniform was introduced in 1883, consisting of a white single-breasted tunic with stand-up collar and shoulder rank boards, white trousers and shoes and pith helmet.26 This became the current summer

undress uniform or ‘ice-cream suit’.

In 1889, a blue double-breasted ‘monkey’ jacket was introduced for everyday wear.27 This became the current winter undress ‘fives’ jacket, after frock coats and cocked hats were abandoned in 1939—but not formally abolished until 1950, essentially because they had become unaffordable.28

In 1915, Engineer Commanders and above received the same oak leaf ‘brass hat’ motifs on their cap peaks that had previously only been worn by seaman officers.29 This was extended to all other officers (including surgeons), in 1918, along with the ‘executive curl’.

Table 1: RN and RAN Non-Executive Officer Distinction Cloth Colours25

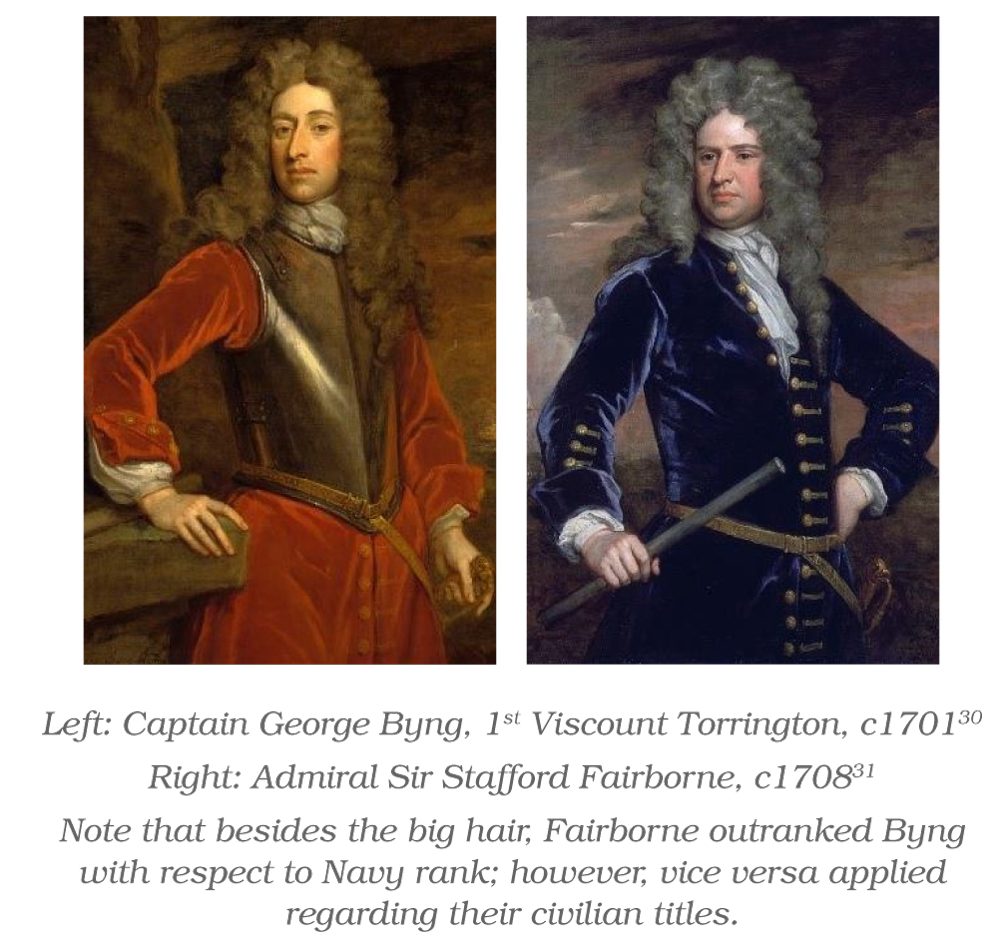

Officer Clothing, c1700

Officer Uniforms, 1748

Officer Uniforms, 1767

Officer Uniforms, 1783

Officer Uniforms, 1795

Officer Uniforms, 1812

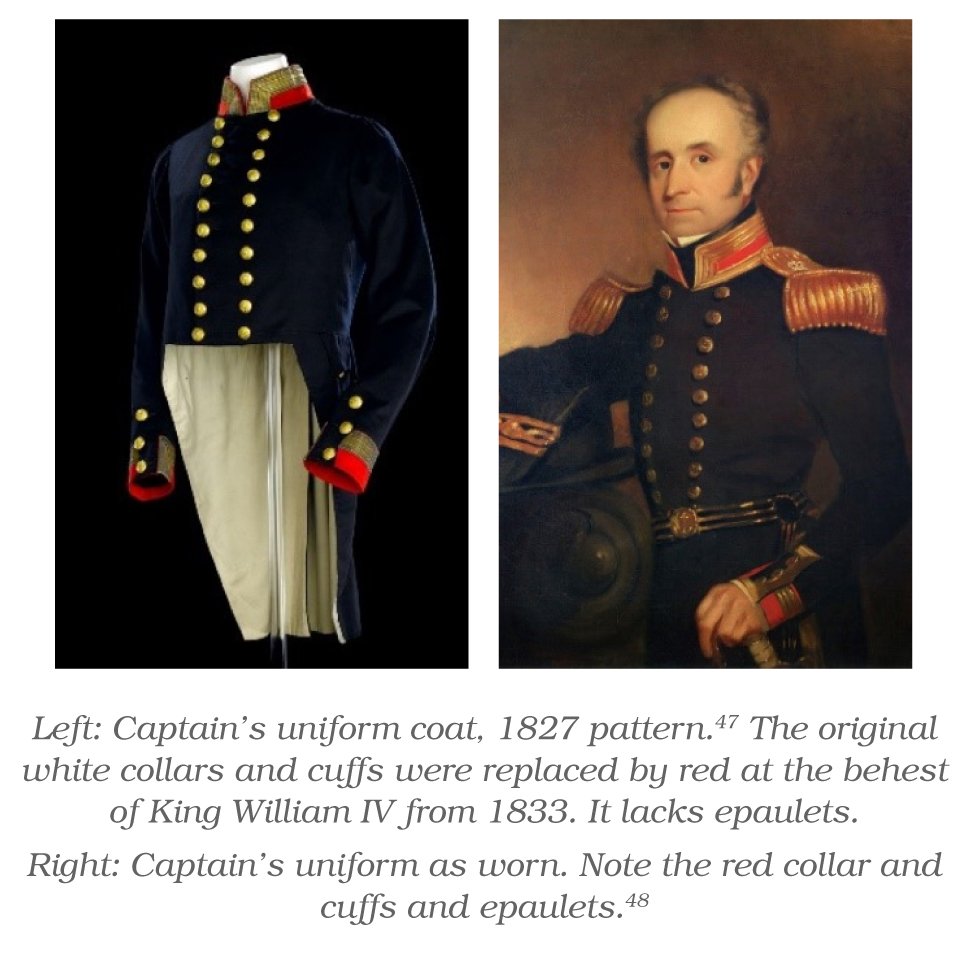

Officer Uniform, 1827

Officer Uniforms, 1843

Officer Uniforms, 1856

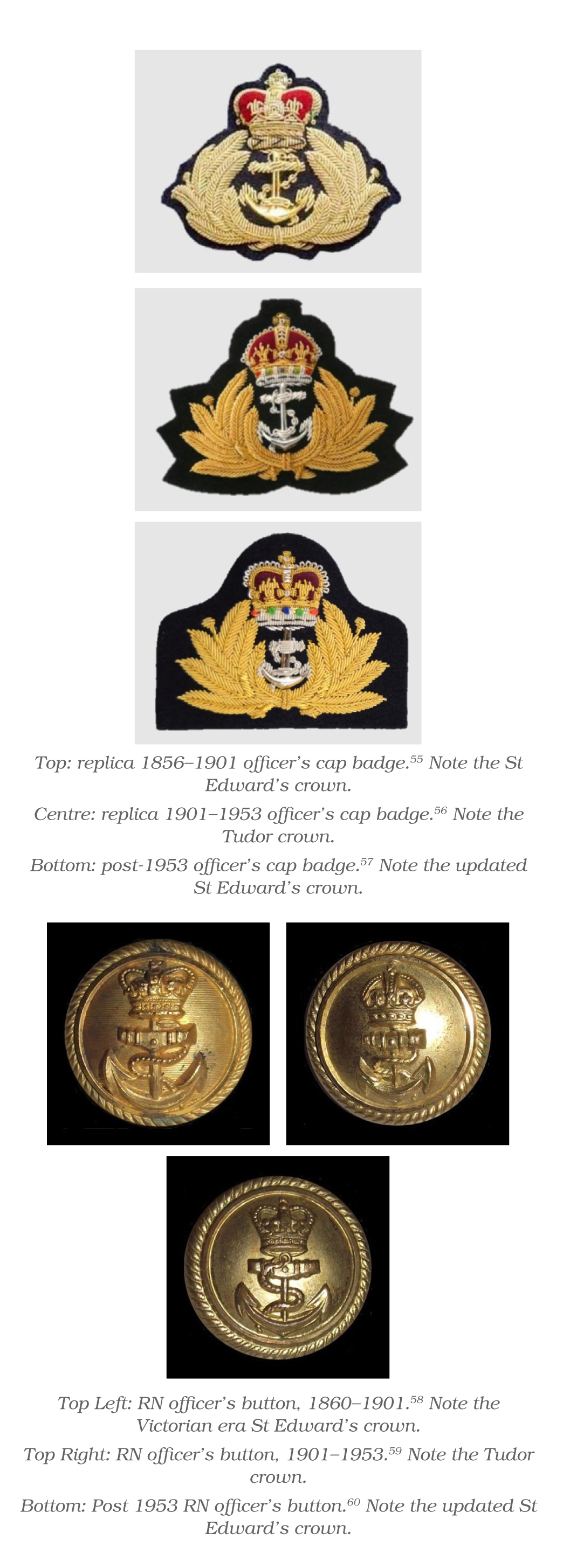

The St Edward’s crown worn on all Navy uniforms during the Victorian era was displaced by the Tudor crown in 1901, on the accession of Edward VII. The accession of Elizabeth II in 1953 resulted in a return to the St Edward’s crown used today.

Male Reserve RN officer uniforms

The occupational mobility of sailors and ‘tarpaulin’ officers between private merchantmen and the King’s ships largely negated the need for a ‘reserve’ as understood today until the 1850s. Technological advances, and a recruiting shortfall at the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853, led to the establishment of the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) in 1859.61 Initially intended for sailors only, the RNR was extended to officers from 1862. All RNR members were recruited from the merchant service and underwent brief periods of gunnery and other Navy-specific training.62

However, the further expansion of the RN prior to World War I resulted in the establishment of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) in 1903. RNVR personnel had no professional seagoing background, but underwent limited shore training before brief periods at sea.63 It was widely said during the war that RN officers were gentlemen trying to be sailors, RNR officers were sailors trying to be gentlemen, while RNVR officers were neither trying to be both. By the end of World War II, 88% of all RN officers (50 000) were RNVR.64

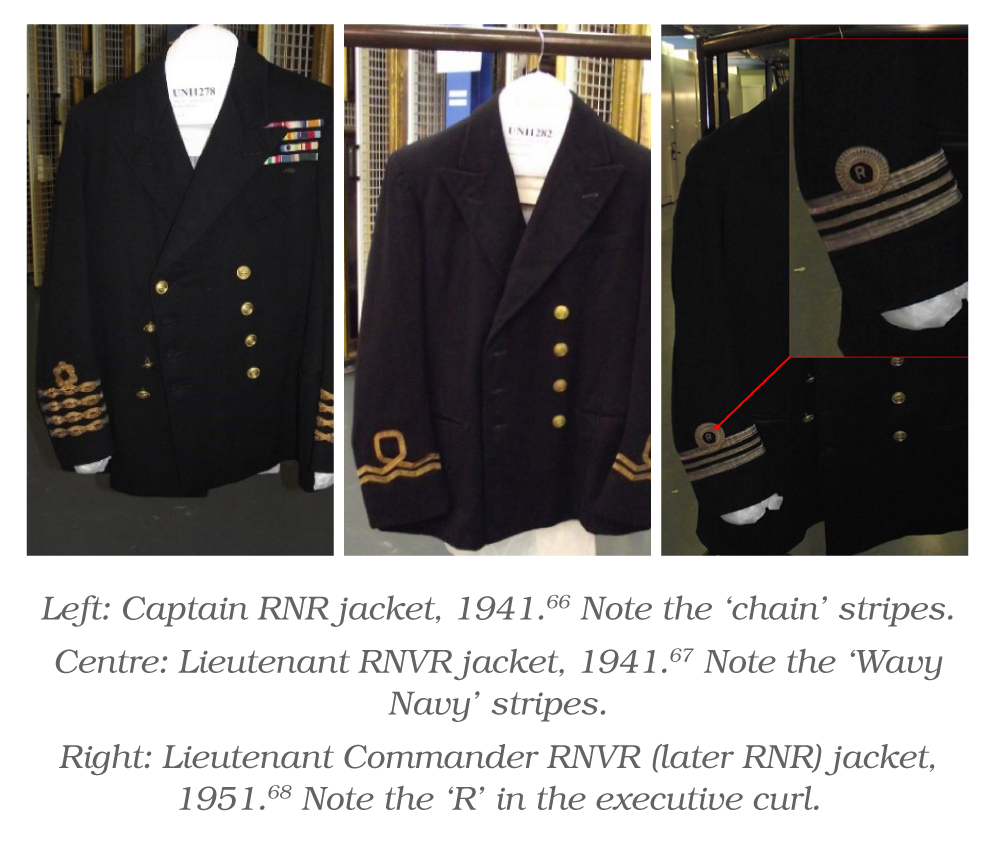

RNR and RNVR officers were distinguished from their RN counterparts by their stripes: RNR officers had an intertwined chain pattern, while RNVR stripes had a ‘Wavy Navy’ pattern. In 1951, RNR and RNVR officers received the same stripes as RN officers, with an ‘R’ in the executive curl. Both Reserves were amalgamated into a single RNR in 1958, with the same uniform as RN officers being worn after the ‘R’ was abolished in 2007.65

Reserve Officer Uniforms

Male RAN uniforms

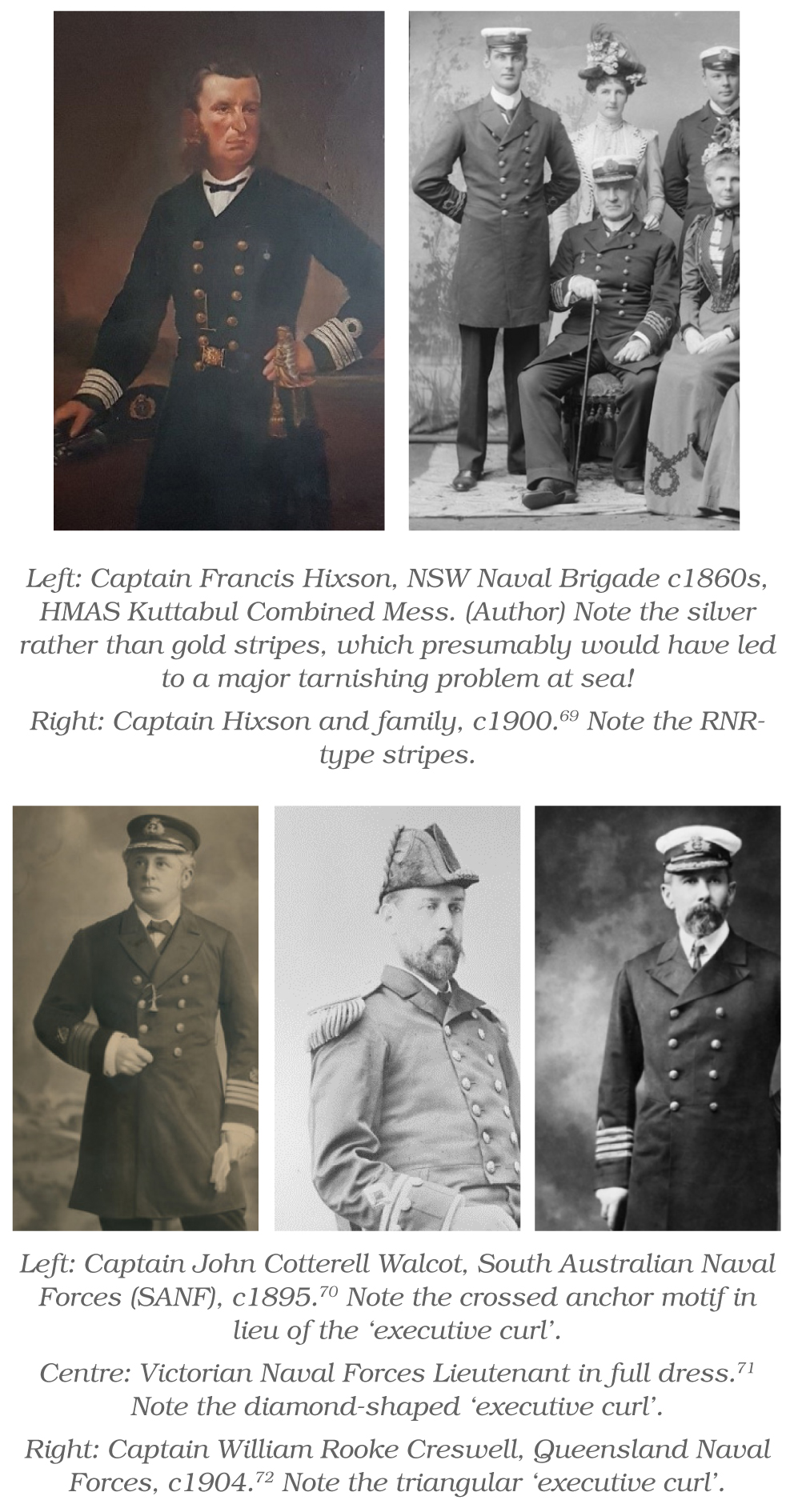

Except for Tasmania and Western Australia, each of the Australian colonies had their own volunteer naval forces from 1853 until Federation in 1901. A key consideration for the colonial naval officers was not being mistaken for being RN, especially in Sydney where the Australian Squadron were based.

RAN Officer Uniforms

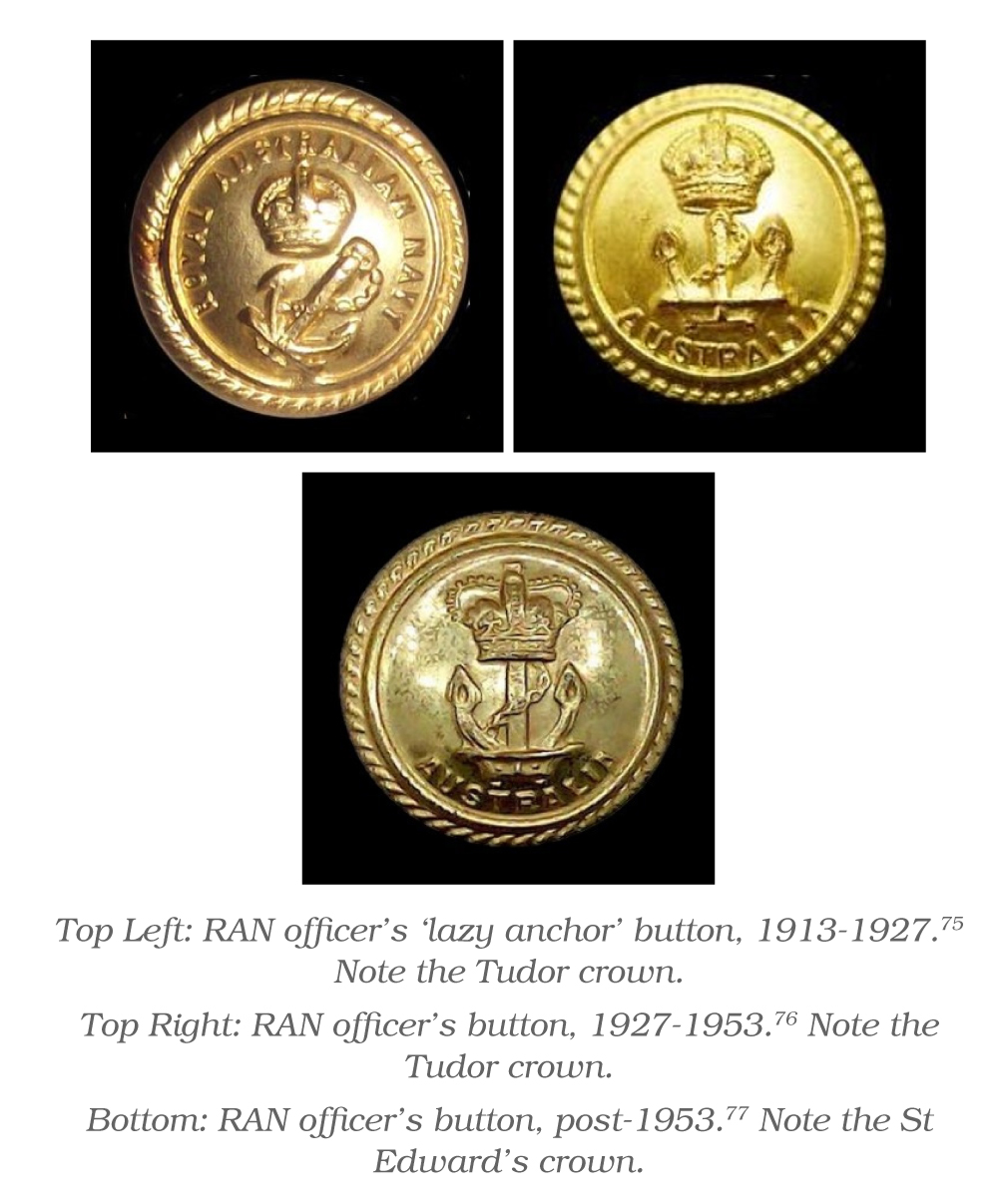

The establishment of the RAN in 1911 led to the adoption of RN uniforms, apart from RAN-specific buttons.73 These used an oblique ‘lazy anchor’ pattern until 1927, when they were replaced by the current vertical pattern. The Tudor crown was replaced by the St Edward’s crown in 1953. In 1965, ‘Australia’ flashes were added to all RAN uniforms, apart from some flag officer items.74

When RAN personnel were posted to the US from 1963 to pick up the guided missile destroyers Perth (DDG 38) Hobart (DDG 39) and Brisbane (DDG 41), permission was granted for them to wear khaki uniforms.78 In 1966, permission was also granted for officers to wear Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) shirt collar rank insignia.79 Khaki uniforms continued to be worn by DDG officers for Vietnam deployments until they ceased in 1971, while other officers deploying to Southeast Asia with the Far East Strategic Reserve continued to wear non-khaki uniforms. The collar rank insignia were replaced in the mid-1970s by the current shoulder rank slides, worn on winter shirts and ‘woolly pullies’ with shoulder tabs.80

Australian Naval Reserve Officers

Multiple name changes notwithstanding, the reserve Australian naval forces differed from the RN in generally having three rather than two components. The RAN Reserve (RANR) was established in 1911, for officers and sailors with a regular (and at various times compulsory) shore training obligation, while the RAN Reserve (Seagoing) or RANR(S) was established in 1913 for professional seafaring officers. The RAN Volunteer Reserve (RANVR) was formed in 1921 for officers and sailors who were available for call-up but did not undertake regular training.82

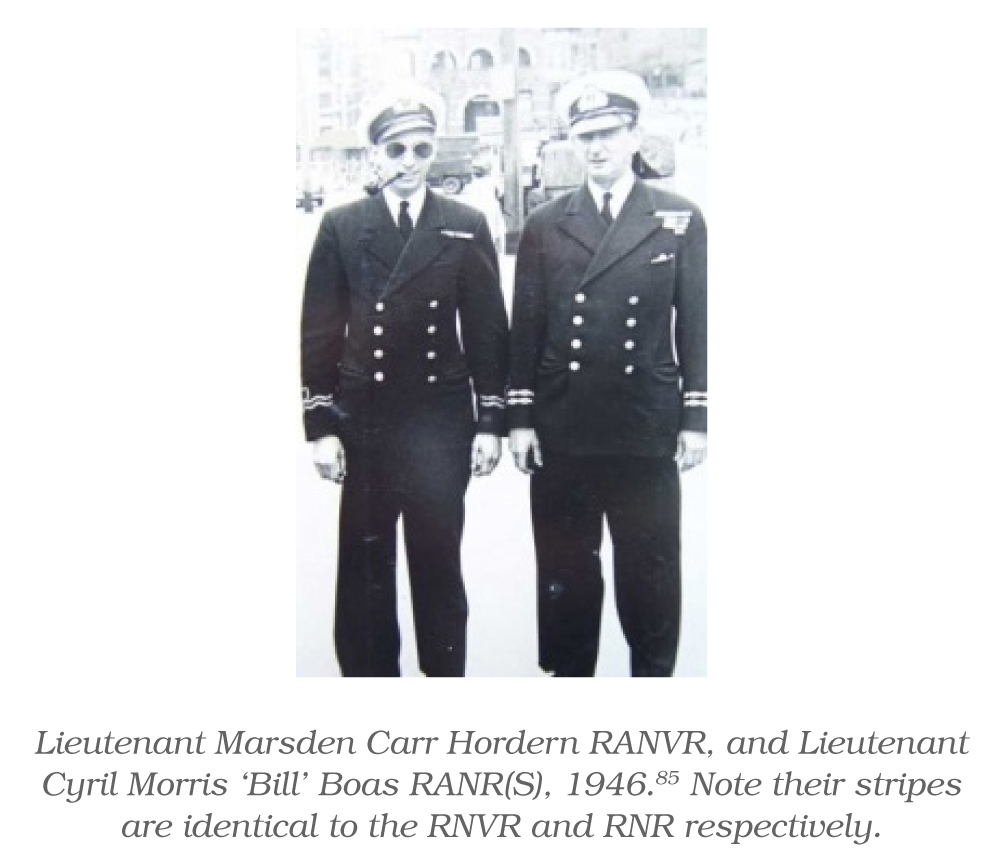

RANR(S) officers wore the same stripes as the RNR, while RANR and RANVR officers had the same stripes as the RNVR. All three reserve forces had standard RAN buttons.83

In 1973, all three reserve forces were amalgamated into a single RANR, with their officer stripes changing to the PN pattern with the same ‘R’ within the executive curl as the RNR. The ‘R’ was abolished in 1986, leaving RANR officers with the same uniform as PN officers.84

British and Australian Women’s Naval Services

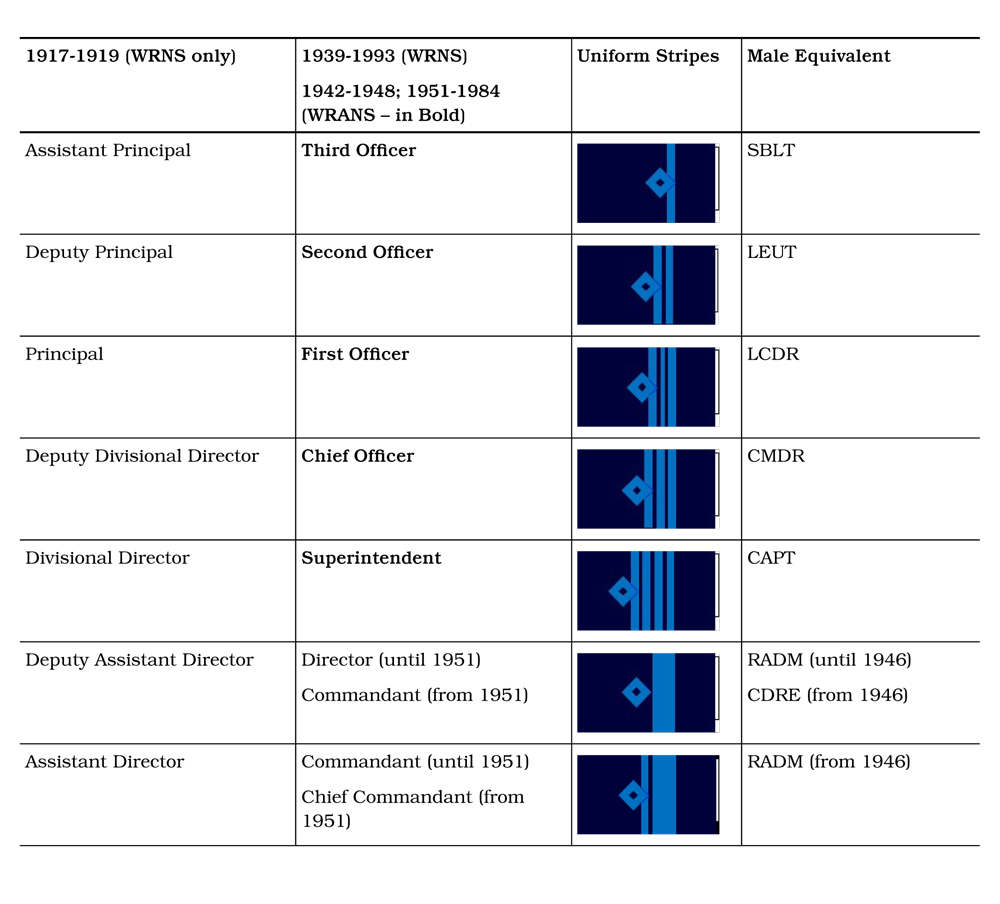

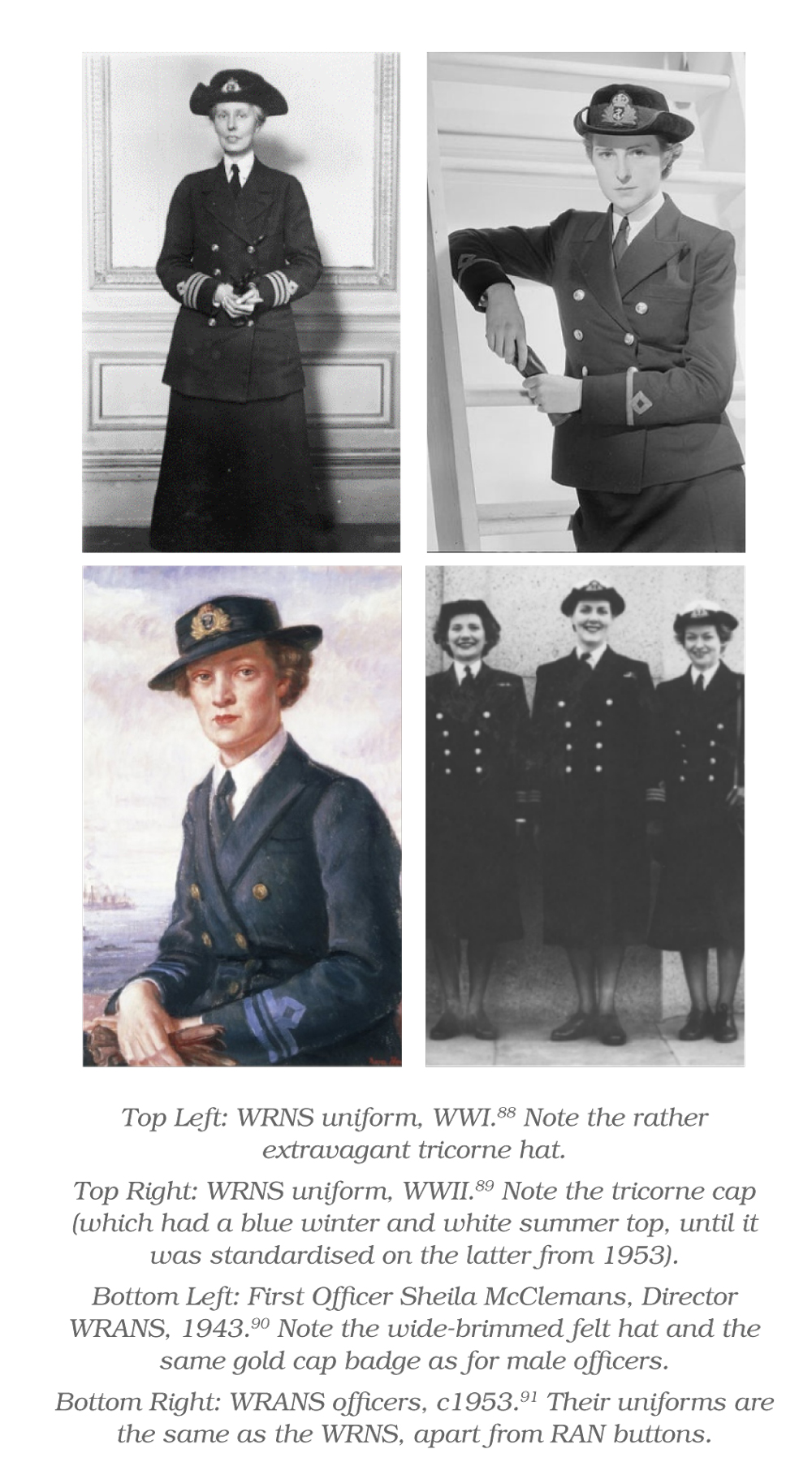

The RN first introduced the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) or ‘Wrens’ during WWI. After an interwar hiatus, the WRNS was re-introduced in 1939 and continued until its integration into the RN in 1993. The wartime Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) was instigated in 1942 and was abolished in 1948. It was reconstituted in 1951 and was incorporated into the RAN on 7 June 1985.86

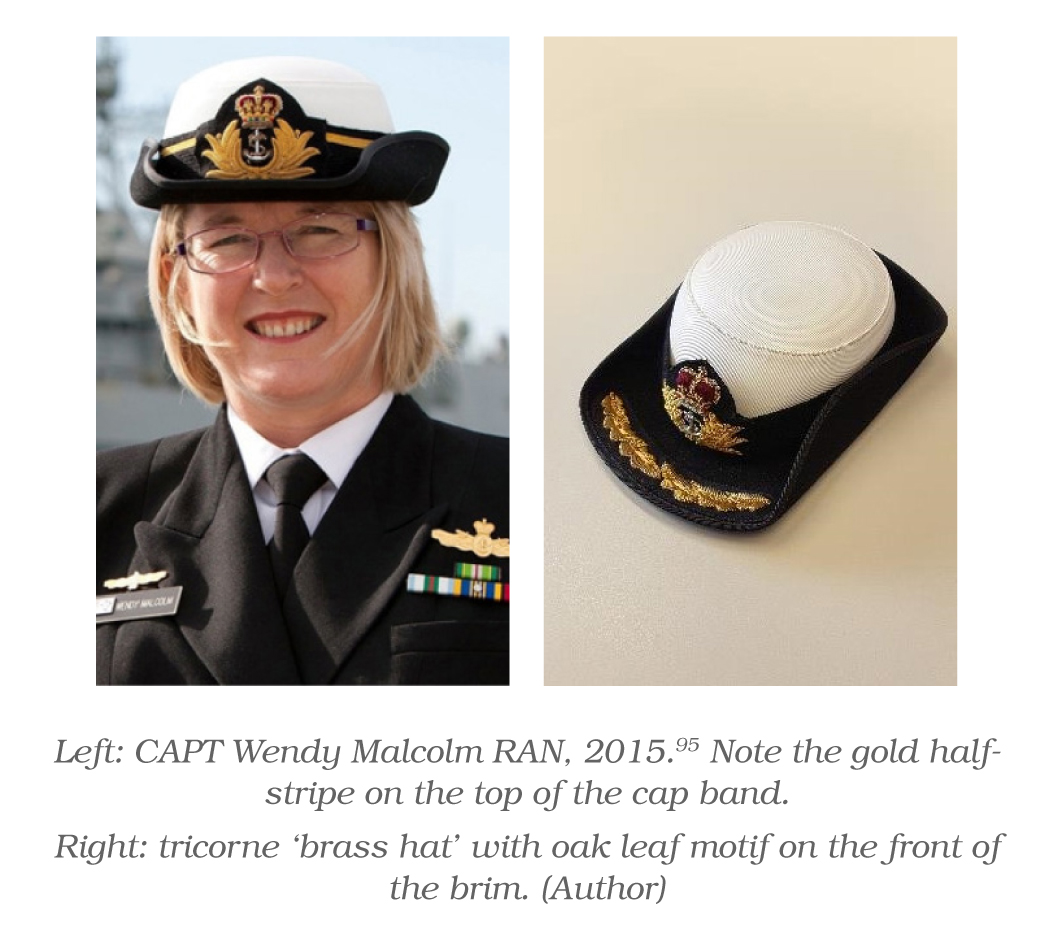

The wartime WRNS and WRANS officer uniforms consisted of a double-breasted jacket with gilt buttons, matching skirt, and blue rank stripes and titles based on the merchant service. WRNS officers wore a tricorne cap (the WWII version remaining in use to this day) with a blue cap badge, while wartime WRANS officers wore a broad-brimmed felt hat with the standard male gold cap badge.

The postwar WRANS officer uniform was essentially identical to that for the WRNS. Following their integration into the RAN, the blue half-stripe on the top of the cap band for female commanders and above were replaced by gold, which was in turn replaced from 2013 by the same oak leaf ‘brass hat’ motifs on the front of the cap brim as for male officers.87

Table 2: WRNS and WRANS Rank and Insignia

RAN warfare badges

British Royal Naval Air Service aircrew wore a gilt eagle on their left sleeve from 1914 until 1918, when they were taken over by the Royal Air Force. On returning to the RN in 1939, they reverted to embroidered ‘wings’ on their sleeves. The RAN followed suit for its aircrew from 1947 until 1966, when they received gilt ‘wings’ worn on the left breast.96 The RAN also became the first Commonwealth Navy to award ‘dolphin’ badges to its submariners at that time.97

Principal Warfare Officers or PWOs (now known as Maritime Warfare Officers or MWOs), have worn gilt chest badges since 1990. Having lost their distinction cloths in 1956, charge-qualified Supply (now Maritime Logistics) and Engineer Officers received their own badges in 1999, along with qualified Hydrographic (now Maritime Geospatial), Mine Warfare and Mine Clearance Diver Officers.98

Sea Readiness Badges (SRBs)

SRBs have been issued since 2000, to indicate the member’s current deployability and accumulated sea time. The latter is indicated by four SRB grades at four-year intervals.99

Summary

Throughout Navy history, there has been a struggle for status, firstly between (and within) the commissioned and warrant officers, and later between (and within) the ‘civil’ and ‘military’ branch officers. It can be argued that since their introduction for commissioned officers in 1748, and for warrant officers in 1787, uniforms have been a weapon, and an expression, of these battles. It can also be argued that women RN and RAN officers fought the same

battle for status throughout the 20th century, noting that for much of this time they were only considered ‘of’ rather than ‘in’ the Navy.

Unlike Navy sailor uniforms, which not only identified sailors as such but were also intended for functional wear at sea, Navy officer uniform styles have tended to reflect contemporary civilian fashion. This article has shown how this has led to a steady (if at times delayed) simplification of clothing styles over the last 270 years. In addition, the replacement of different uniforms for each rank by a standard uniform with rank embellishments from the 1840s limited uniform costs, particularly for junior officers who lacked a second income. Both factors especially came to the fore during and after World War II, which resulted in Navy officer uniforms that largely remain extant today.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the RAN, or any of the other organisations mentioned.

Corresponding Author: Neil Westphalen, neil.westphalen@bigpond.com

Authors: N Westphalen1

Author Affiliations:

1 Royal Australian Navy Reserve