Abstract:

Background

In 2010, prostate cancer was found to be the fourth leading cause of death in Australia. Studies indicated that Vietnam veterans reported up to twice the incidence of prostate cancer compared to the general population.

Purpose

To compare ADF men with civilian men regarding their awareness and knowledge of (1) symptoms, (2) screening and (3) treatment of prostate cancer.

Material and methods

An anonymous questionnaire comprising 12 questions was distributed to adult men at an ADF defence barracks in Melbourne and at the Monash University Clayton campus. Six questions were single answer and six allowed for multiple choices.

Results

A total of 250 completed questionnaires were analysed (51 ADF and 199 civilian). Overall, little difference was found in the responses from the two groups . Of the total sample, more than 75% had seen their GP within the last six months and 90% had heard of prostate cancer, yet few had discussed the topic with their GP, had ever been checked, or knew someone with prostate cancer. Overall knowledge was low about symptoms, tests, treatment options and outcomes of prostate cancer. Concern about having prostate cancer varied, with around half indicating a small amount of concern.

Conclusion

With increasing incidence rates and poor awareness, combined with misconceptions and a failure to discuss the topic with their GP, men’s knowledge about prostate cancer is of concern. Information is now available online via the ADF and with the growing interest in social media and online campaigns; increased public awareness may lead to more men being tested even when they feel well and have no symptoms.

Key words/phrases –

- Prostate cancer awareness,

- Australian Defence Force (ADF)

- Symptoms, tests, treatment

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest.

Introduction

In 2010, prostate cancer was the fourth leading cause of death in men ,with 3235 men losing their lives [1]. Although prostate cancer is rare in men under 40 [2] and mortality rare under 60 [3-5], men as young as 23 have undergone initial biopsy for prostate cancer [6]. Incidence rates for prostate cancer have increased in Australia in recent years, from 79.7 cases per 100,000 men in 1982 to 189.5 cases per 100,000 in 2008 [7].

Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel are required to maintain a high level of physical fitness and conform to medical standards to ensure they are able to meet the rigorous demands of service life. This includes a comprehensive periodic health examination (PHE), the frequency of which is based on age and service [8]. Defence personnel of the regular force and reservists on full time service have free access to medical care and support is provided for wounded or ill members [8].

While no studies could be found for the wider ADF personnel regarding prostate cancer rates, two studies were found about the morbidity and mortality of Australian Vietnam veterans. The Australian Vietnam veterans health study found of 40,030 veterans surveyed, 428 reported they were diagnosed with prostate cancer [9]. The follow-up validation study validated 212 of the 428 cases of prostate cancer [10, 11] and reported that, when compared to the wider Australian community, the results suggested that Vietnam veterans had a ‘significantly higher prevalence than in the wider Australian community’ [10]. A second study of ADF men who had served in Vietnam found that although there was a doubling of prostate cancer risk when compared to the wider community, the findings were not statistically significant [11]. However, this may have been due to the increased rates of screening in the post-PSA (prostate specific antigen) era.

A study of cancer incidence in the United States of America military population also found that prostate cancer rates were twice those in the general population [12]. One possible causative factor for the increase in the military population studied is the exposure to herbicides in Vietnam. During the three decades that Australian and American forces were deployed to Vietnam, particularly in the years from 1962 to 1971, personnel were exposed to chemicals including herbicides known as Agent Orange [11] and depleted uranium (material used in armour penetrators) [12].

Nonetheless, in Australia, population-based screening for prostate cancer is not currently recommended because it is said that there is insufficient evidence to support routine screening [5, 13]. The most recent Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) guidelines for general practitioners (GPs) do not recommend PSA screening [5]. However, screening was recommended in the past [14, 15] and is currently recommended by the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (USANZ) – “ … to be offered to men in the 55-69 age group under certain circumstances, … and to men as young as 40 who have concerns, having a single PSA test and digital rectal examination (DRE) performed to stratify their risk and develop a personalised screening monitoring plan” [16].

Outcomes from the Australian Vietnam Veterans Health study [9] include the publication of a booklet about prostate cancer which is available online [17]. The Men’s Health Peer Education (MHPE) [18] was also set up online in 2007 to raise awareness about men’s health issues and in recognition that Vietnam veterans were reported as having a higher incidence of certain conditions including prostate cancer [18]. This raises the question of where do men find accurate information about the symptoms and treatment of prostate cancer, given that men find the topic embarrassing [19] and/or incorrectly thinking that symptoms for prostate cancer are the same as those for benign prostatic hyperplasia [3, 19, 20]. An emerging source of information, other than the GP, is through discussions on social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter, which are available to the wider community and are rapidly increasing in popularity [21]. Another avenue is via campaigns such as Movember [22], which has a significant link to the ADF as one of the founders had a career in the Australian army and is now CEO of Movember [23].

This aim of this study was to compare ADF men with civilian men regarding their awareness and knowledge of (1) symptoms, (2) screening and (3) treatment of prostate cancer. .

METHODS

A questionnaire comprising 12 questions was developed following consultation with the literature and it was tested for reliability by six GPs from the Department of General Practice, Monash University. Of the 12 questions, six required a single response and six provided for multiple responses [24]. The completed questionnaires were presented anonymously.

Participants:

Men over the age of 18 from (a) ADF men at a Defence Barracks Melbourne and (b) civilian men at Monash University Clayton Campus were invited to complete the questionnaire by members of the research team (KJ and RS).

Data Collection:

All men who appeared to be over the age of 18 were approached by a member of the research team (KJ, RS) and invited to anonymously complete the questionnaire. If the men agreed to participate, they were provided with the explanatory statement and the questionnaire to complete in isolation . Selection bias was avoided as much as possible by the researchers approaching all men who appeared to be over the age of 18. Informed consent was implied when the anonymously completed questionnaire was handed to the researchers.

Data analysis:

All data was entered and analysed in SPSS19 for descriptive results only [25].

Funding: There was no funding for this research.

Ethics: was approved for this project through Monash University HREC.

RESULTS:

A total of 250 completed questionnaires were returned from ADF men (n=51) and civilian men (n=199) at Monash University, Clayton campus. Results are reported for the full cohort (n=250 = 100%), and for the purpose of making some comparison between the two groups, results are also reported for ADF men (n=51 = 100%) and civilian men (n= 199 = 100%)

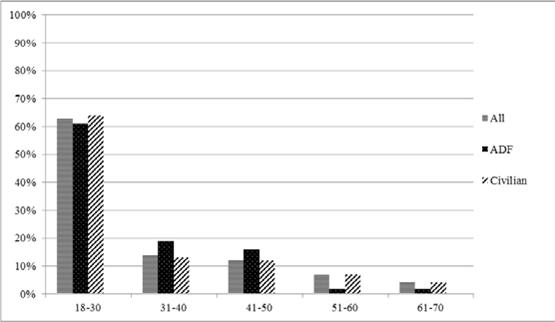

Demographics: Men were asked their age only. There was little difference in the two groups for all age brackets, with more than 75% of the cohort in both groups being under 40 years of age (Figure 1). This is important, as men in this age range are rarely included in studies about prostate cancer [2, 20] and are under the age when prostate cancer testing is recommended by USANZ [16, 26] . However, because the spread in both groups across the age range is similar, outcomes for both groups can be compared.

Figure 1: Age across ranges for ADF and civilian men (n = 250: ADF n = 51 / Civilian n = 199)

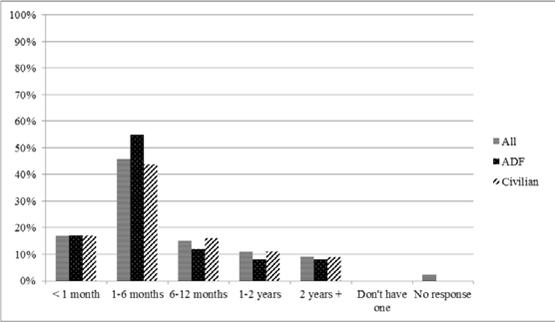

The majority of participants (92% ADF / 86% civilian) had heard of prostate cancer, but more than two-thirds (67% ADF / 68% civilian) indicated they did not know anyone who had prostate cancer. ADF men were more likely to have seen a GP in the past six months (55% ADF / 44% civilian); but this may be because of ADF requirements [18]. Whether ADF men included their annual medical check as a visit to the GP is not known, nor is it known whether the ADF men saw a GP in addition to ADF medical checks [18]. The majority of men (92% ADF / 88% civilian) had contact with the medical profession over the past two years, thus there was an adequate opportunity for prostate cancer to be discussed [4, 20, 21]. Yet less than a quarter of the men (20% ADF /21% civilian) had discussed the topic with their GP and fewer (16% ADF / 19% civilian) had been checked for prostate cancer (Figure 2).

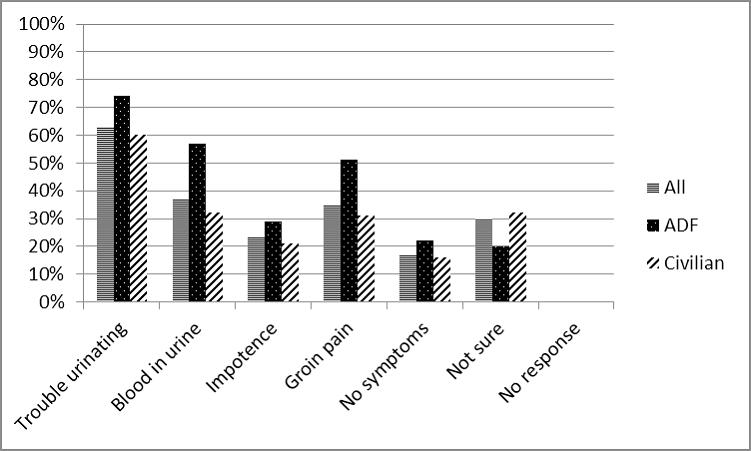

Figure 2: When did you last see a GP

Although prostate cancer is a common cancer for men in Australia [2], only around a third (29% ADF / 30% civilian) indicated they, or someone they knew had prostate cancer. Regarding symptoms, ADF men were slightly more likely to indicate ‘no symptoms’ (22% ADF / 16% civilian) but civilian men were more likely to be unsure (20% ADF / 32% civilian) despite the fact that prostate cancer rarely has symptoms [2, 14]. The high percentage in both groups who selected “ trouble urinating” (63%) is consistent with literature that suggests many men do not understand the difference between prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia [19], the latter not generally associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer [5] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Symptoms for early prostate cancer

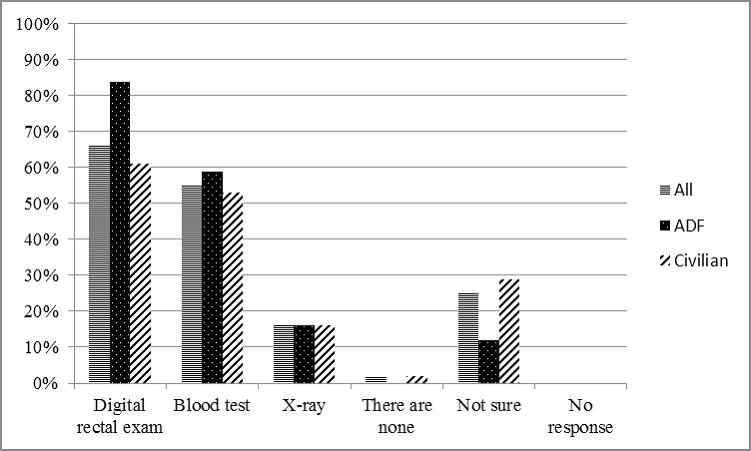

Regarding tests to check for possible signs of cancer, ADF men were less likely to be unsure than civilians (12% ADF / 29% civilian), but slightly more aware of digital rectal examination (DRE) (84% vs. 61%) and blood tests (59% vs. 53%), suggesting that ADF men may be accessing information provided by Veterans Affairs [17, 18]. Few indicated ‘there are no tests to check for the possible signs of cancer (0% ADF /2% civilian) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Tests to check for possible signs of cancer

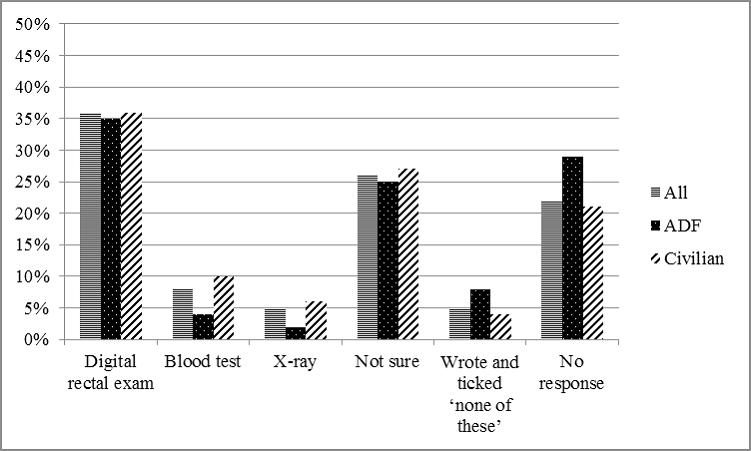

Over a third of the men (35% ADF / 36% civilian) indicated that a digital rectal examination (DRE) would make them so uncomfortable they would avoid being tested. Few felt a blood test (4% ADF / 10% civilian) or an x-ray (2% ADF / 6% civilian) would stop them from being tested. Around a quarter (25% ADF / 27% civilian) were not sure, or wrote and ticked ‘none of these’ (29% ADF / 21% civilian), or did not respond to the question (8% ADF / 4% civilian) (Figure 5). Whether or not educating men about the tests available would impact on their decision to be tested or not because of discomfort is not known.

Figure 5: Which of these tests (if any) would make you so uncomfortable that you would avoid being tested

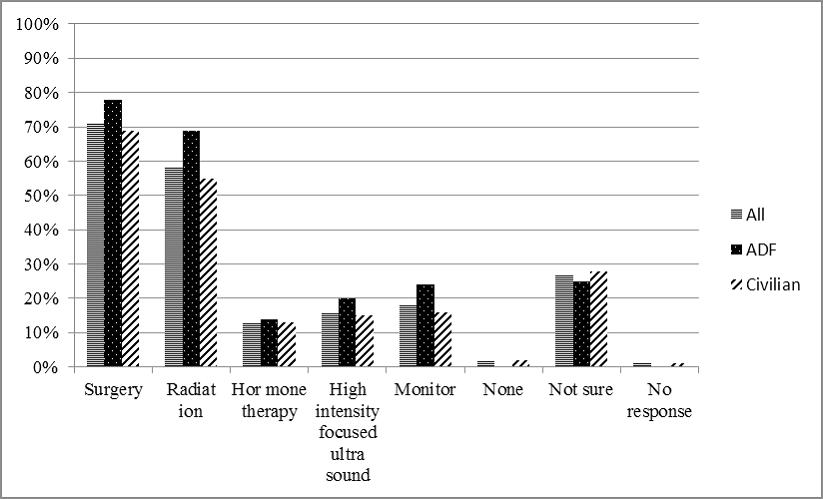

All treatment options listed are options for prostate cancer, depending on the patient [5, 16-18] . Around two-thirds of the men indicated they were aware of surgery (78% ADF / 69% civilian) or radiation (69% ADF / 55% civilian) as treatment options. Fewer indicated awareness of hormone therapy (14% ADF / 13% civilian), high intensity focused ultra sound (20% ADF / 15% civilian) or monitoring (24% ADF / 16% civilian). Of note, around a quarter (25% ADF / 28% civilian) were unsure of treatment options (Figure 6)

Figure 6: Treatment options for prostate cancer (can be more than one)

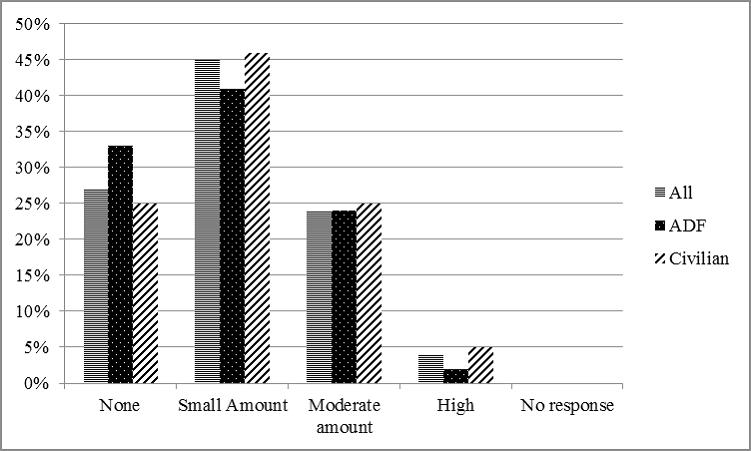

The level of concern participants had with regard to prostate cancer affecting themselves varied. Around half (41%ADF / 46% civilian) indicated a small amount, with around a quarter of the men indicating no concern (33% ADF / 25%) or moderate concern (24% ADF / 25% civilian). Few (25% ADF / 5% civilian) indicated high concern (Figure 7).

Figure 7: What level of concern do you have with regard to prostate cancer and yourself

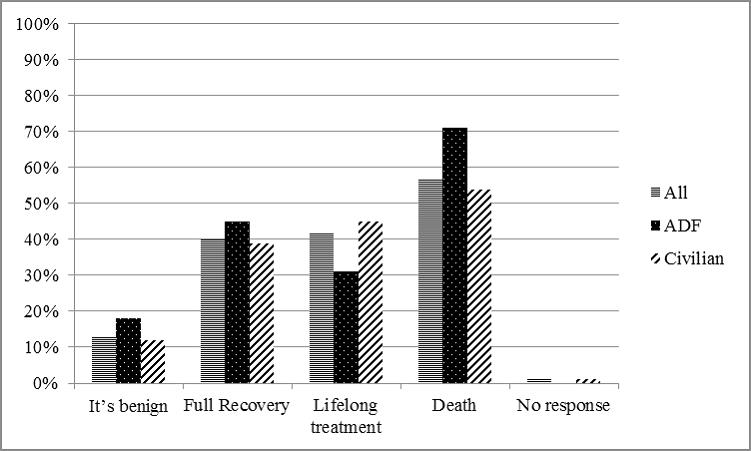

Few men thought the outcome of prostate cancer was benign (13% ADF / 18% civilian), with around half thinking the outcome was either full recovery (40% ADF / 45% civilian) or lifelong treatment (42% ADF / 31% civilian). More than half thought that death was the outcome of prostate cancer (57% ADF / 71% civilian) (Figure 8).

Figure 8: What do you think the outcome of prostate cancer can be

DISCUSSION

The results from this study indicate that awareness of and knowledge about the symptoms, screening and treatment of prostate cancer was similar in both groups. Given the resources provided for ADF men by the Department of Veterans Affairs [17, 18] as a result of the research into Vietnam veterans health [9, 10], it was surprising that there was little difference in ADF men’s knowledge and actions to be checked for prostate cancer, when compared with that of civilian men. Although previous research suggested that Vietnam veterans may be twice as likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer than men in the wider community [9-11], the results of this research suggest that ADF men have a similar level of knowledge about the symptoms and treatment of prostate cancer as those in the wider community. Whether Australian Vietnam veterans’ exposure to herbicides was the primary link for these men to develop prostate cancer is unclear [9, 11]; the lack of difference in knowledge may also reflect an indifference to this disease.

While the majority of the cohort had seen a GP within the last two years, RACGP guidelines (which were developed for use by GPs in Australia), do not recommend screening unless the man specifically raises the topic[5]. Thus, if men do not raise the topic of prostate cancer, and if GPs follow the RACGP’s Guidelines, it is possible that no one will raise and discuss it . This is of concern given that there was a high percentage of men in the cohort who had never raised the subject with their GP, particularly when men with a family history are at an increased risk of developing prostate cancer [2]. If the topic is discussed, doctors can individualise the risk for their patients[1], rather than leaving these men potentially with limited knowledge and/or awareness of the symptoms,screening and treatment options .

As prostate cancer is a common cancer in men in Australia, with incidence rates increasing in recent years [7, 27] it was surprising that nearly 70% of the cohort did not know of someone who had prostate cancer. This outcome is significantly higher than previously reported [3]. This suggests poor public awareness of prostate cancer and/or men not discussing the issue with other men or their GPs possibly because of a lack of knowledge, or because they are embarrassed [19]. Not discussing the topic can result in men not having knowledge about symptoms, although there are rarely symptoms in the early stages of prostate cancer [2, 14, 22, 23, 28]. While the disease most often originates in the prostatic glandular acini [2], there is a common misconception that urinary signs occur with prostate cancer and that prostate cancer would be likely to cause impotence [3]. Because of misconceptions, lack of knowledge, feeling well and/or having no symptoms, men may not undergo prostate cancer testing, even though feeling well and not having symptoms does not indicate they are free of prostate cancer [2, 3, 20, 23].

Sources of information for prostate cancer are available online via Veterans’ Affairs [17, 18]. In addition, information is available via social media such as Twitter and Facebook which are growing in popularity [21]. The increasing use of online fora to access information in general may result in men accessing information about prostate cancer [21]. Campaigns such as Movember [22, 23] also provide information to raise awareness of men’s health issues including prostate cancer; the campaign also aims to raise money for prostate cancer research and to become a global communication conduit for raising awareness of men’s health issues [21].

There were a number of limitations in this study including the generality that the results may be limited by the relatively small numbers (250 participants) and that the ADF men were not asked to clarify whether they had seen a GP in the community or interpreted their annual medical check as seeing a GP. While the study questionnaire did not differentiate between seeking a GP in the community or seeing an ADF medical officer, as medical officers who serve in the ADF are trained in the wider community along with their colleagues who practise in the community, this lack of differentiation should have little impact on results. However, it is important to note the high number of participants who reported limited awareness and knowledge about the symptoms and treatment of prostate cancer.

Although the two groups were not purposively matched for age, results indicate that the percentage of participants in each age group was similar. As the majority of participants were 40 years or younger (77%), this research is important given this cohort’s limited knowledge and their interaction with social media which suggests that men under 40 years of age are actively using social media to seek information about health issues including prostate cancer [21, 23].

Conclusion:

There was little difference found between either group regarding their awareness and knowledge about symptoms, screening and treatment options for prostate cancer and this , may be of benefit to men now and in the future. For ADF men, attendance at parade nights provides a unique opportunity for specific health issues to be addressed, an opportunity not available to men in the wider community. For all men, more open discussions with GPs about all aspects of their health would assist men to make better informed decisions. The increasing use of social media provides a forum for accessing information ,particularly when the information available is accurate. For medical personnel, clear and unambiguous guidelines[5, 16], particularly for the treatment of prostate cancer,would be of benefit to all.