Abstract

Previous research suggests that public estimates of mental health problems in US veterans who returned from the deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan exceed actual concerns. The present project examines how sociodemographic factors may contribute to victimising perceptions of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans by conducting a free word-association task. A total of 245 US participants provided three open-ended word associations to ‘US Army Iraq Veterans’ and ‘US Army Afghanistan Veteran’ and completed a sociodemographic questionnaire. Multiple linear regressions outline that higher social distance towards US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans predicts elevated victimisation scores. A semi-structured, qualitative interview study examined the underlying rationalities of victimising sentiments in 10 participants with no contact and 10 participants with close contact with US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans. The thematic analysis suggests that social distance towards US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans mitigates the victimisation and stigmatisation of veterans. This was the case as those with close contact to US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans had explicit knowledge about which jobs veterans accomplished. In contrast, those who did not know US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans equated deployments with killing, front-line fighting and witnessing atrocities. Implications and conclusions are discussed.

Keywords: Victimisation; Veterans; Civil-Military Relations; Mental Health;

Introduction

An important though understudied aspect of the experience of United States (US) Military veterans’ is the process of their transition into civilian life.1,2 While the majority of US Military veterans reintegrate successfully, demographic research outlines that high rates of veterans are unsatisfied with their transition experience,33 and are more likely to suffer from suicidal ideation, unemployment, alcohol or substance abuse and homelessness than members of the civilian population.4-11 To date, research mainly examines difficulties in the US veterans’ transition in relation to mental health difficulties that some veterans experience.12 Yet, how societally prevalent, negative perceptions of US veterans may impact the reintegration into civilian life remains unaddressed.

Particularly since 9/11, military service has become publicly associated with mental health problems such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression.13 Specifically, studies suggest that veterans in the media are commonly represented in the context of suffering and injury.14 For example, between 2003 and 2011, a total of 73% of articles in the New York Times and the Washington Post focused on mental and physical health problems when representing US veterans who returned from Iraq or Afghanistan.14 These negative representations of veterans who returned from Iraq and Afghanistan are mirrored in polls and surveys with representative sample sizes of the US population.3,15,16 Polls and surveys suggest that public estimations of mental health problems of veterans who returned from the deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan exceed actual concerns.13,15

Negative and victimising attitudes towards veterans may have problematic consequences and impede a successful transition to post-military life. Specifically, the attribution of veterans suffering from mental disabilities may increase levels of stigma. As mental disability labels include numerous negative stereotypes such as being dangerous, unpredictable, dirty, worthless, weak and ignorant,17 veterans may face implicit discrimination that diminishes a person’s competence.15 In addition, research suggests that veterans who perceived a lack of respect and pride for homecoming were more likely to have problems adapting to civilian life and experiencing PTSD and suicidal thoughts.18-22 In fact, homecoming support was a stronger predictor of PTSD and suicidal thoughts than theatre or combat exposure itself.18,22 In conclusion, negative perceptions of veterans and stereotypes relating to anticipated or explicit mental health problems of veterans may lead to societal rejection, referring to deliberate actions to avoid those with mental health problems or excluding them from social interactions.24,25

These problems may be particularly pre-eminent for Army veterans who have returned from the most recent deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. With this younger veteran population, negative perceptions and victimising sentiments may affect the veteran’s economic situation. Moreover, as research finds people relate mental disability particularly to combat experience,16 and combat experience to the Army,26,28 veterans who were part of the Army may be particularly prone to stigmatisation and discrimination.

However, to date, surprisingly little is known about why members of the US public may hold victimising sentiments about US veterans who returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. If this type of research was done, it examined mainly how victimising perceptions of veterans were exhibited in controlled conditions. For example, using an Implicit Association Test (IAT), Schreger & Kimble2 outlined that participants held an implicit bias of mental instability towards veterans. While Schreger & Kimble’s innovative approach reiterated findings from representative polls and surveys,3 the question why participants may hold these beliefs remained unaddressed. Similarly, Hipes et al.15 outlined in their laboratory experiment that participants would seek greater social distance towards veterans with PTSD, reiterating evidence from studies examining the stigmatisation and social exclusion of individuals with mental health problems.24 Here, social contact with veterans moderated the deleterious effects of a PTSD label, mitigating the extent to which the participants sought social distance.24 Besides social contact, it is not unreasonable to suspect that long-running lack of public support for the US deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan may influence the victimisation of veterans.29-31 Public support of military interventions was outlined to play a key role in defence and foreign policy.29 Besides justifying appropriate financial resources for the military, sustaining troop morale and military effectiveness,30,32,33 public support also affects public perceptions of mission success and military fatalities.31 For example, public aversion to military interventions was found to be associated with higher estimates of military casualties and mission failure.31 Yet, it remains unclear whether public perceptions of military interventions may also taint perceptions of veterans who participated in these interventions. Prolonged formal education was also outlined to have a negative effect on the public’s willingness to support and participate in war.34 If individuals are unwilling to participate in a war, they may also hold negative attitudes towards those who did. Therefore, prolonged formal education may negatively impact individual perceptions of veterans. Such a possible spillover effect may be particularly evident in public perceptions of US veterans who returned from the unfavourably viewed deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, due to the lack of empirical evidence, the possible effect of sociodemographic characteristics on the victimisation of US veterans remains unclear.

The present explorative study addresses this gap in knowledge by examining which sociodemographic characteristics may contribute to elevated victimisation scores in characterisations of veterans and why they do so. Therefore, Study 1, a quantitative word-association study, investigates which sociodemographic characteristics predict higher victimisation scores. Study 2, a qualitative follow-up interview study, will aim to explain why the sociodemographic characteristics outlined in Study 1 predicted higher victimisation scores. The discussion will synthesise the results and outline the real-world implications of the present findings.

Study 1: Methods

Participants

After receiving ethical approval from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs (IRB 19-064), a total of 245 participants was recruited by advertising the project on social media and at university premises. The participants completed the survey between March 2018 and March 2020. Due to consideration of practicability and feasibility, a convenience sample was recruited. As outlined in Table 1, the recruited population included a high proportion of females, of whom most were well-educated undergraduates. An overview of the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics can be found in Table 1. In comparison, the median age of a US citizen is 38.4 years,35 with 90% of all adults above 25 years of age holding a high school certificate (or equal) and only 35% having at least a Bachelor’s degree.36 Therefore, the present convenience sample was not representative for the US population.

Table 1. Demographic information US survey

| Demographic characteristics | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Gender | Female: 157 (64.1%) Male: 88 (35.9%) Non-binary: 0 (0%) |

| Age | M = 25.12 (SD = 7.63) |

| Education | College/University or equivalent: 136 (55.5%) High school diploma or equivalent: 107 (43.7%) Below high school diploma: 2 (0.8%) |

| Nationality | US Citizen: 231 (94.3%) Other: 14 (5.7%) |

| Opinion about US Armed Forces deployment to Iraq | It was wrong or rather wrong to send the US Armed Forces to Iraq: 155 (63.3%) It was right or rather right to send the US Armed Forces to Iraq: 90 (36.7%) |

| Opinion about US Armed Forces deployment to Afghanistan | It was wrong or rather wrong to send the US Armed Forces to Afghanistan: 131 (53.5%) It was right or rather right to send the US Armed Forces to Afghanistan: 113 (46.1%) |

Materials and procedure

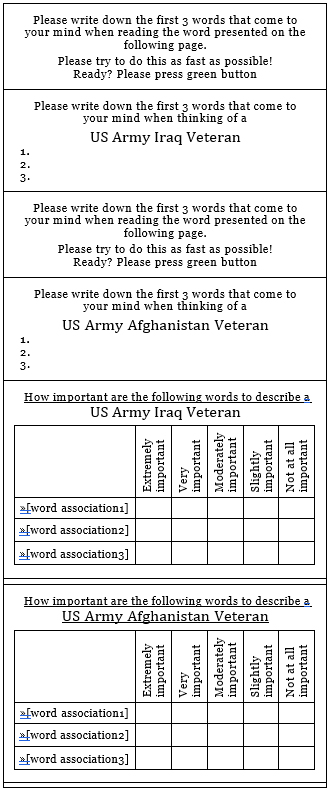

Figure 1 shows the test instrument as presented to the participants. After signing informed consent, the participants provided the following information in an online survey:

- The participants were asked to produce three words that came to their mind when thinking of the stimuli terms ‘US Army Iraq Veterans’ and three words for the term ‘US Army Afghanistan Veteran’ (free word-association task).37-39

- Then the participants were asked to rank the prototypicality of each of their word associations on a 5-point Likert-type scale (extremely important, very important, moderately important, slightly important, not at all important). This process was not timed, and the participants were encouraged to be reflective in their 40,41

- The participants were presented with a questionnaire that included basic sociodemographic measures (cf. Table 1).

Data analysis

A theme-based Content Analysis (CA)42 of the free word associations was conducted to facilitate further descriptive and parametric analyses. A process of grouping together semantically similar answers assisted with data aggregation to reduce ambiguity.37,43 Semantically similar answers that expressed the same content but differed in grammatical form, expression, spelling, etc. were grouped (i.e., Honor— honour, Bravery—brave). The evaluation of saliences, frequencies and characteristics of associations was informed by relevant literature37,44,45 and guided the subsequent construction of the theme-based categories. With satisfactory interrater reliability scores (92.54% interrater concordance), the data was found to be categorised into autonomous and distinctive categories. The data was transposed to SPSS and analysed with a multiple linear regression to examine which sociodemographic characteristics significantly predict the evocation of victimising word associations. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis (MRA) is a commonly used method in exploratory word-association research.39,4 It is a technique for explaining the variation in a dependent variable by observing the relationship with independent variables.

Study 1: Results

Categories were constructed by relating findings from previous literature to the dataset and observing frequencies and similarities within the data.37,47,48 Therefore, inductive and deductive approaches were combined, generating a consistent coding system. In this way, the 1470 associations were categorised into a set of 10 distinct categories. While the number of categories may appear high, it is within the expected range, common in word-association studies.49-51 The word associations were categorised with a predominance of associations falling into the victimisation category (US Army Iraq Veteran = 203 associations [27.61%]; US Army Afghanistan Veteran = 246 associations [33.45%]), the war category (US Army Iraq Veteran = 188 associations [25.58%]; US Army Afghanistan Veteran = 162 associations [22.04%]) and into the heroisation category (US Army Iraq Veteran = 161 associations [21.9%]; US Army Afghanistan Veteran = 175 associations [23.81%]).

Figure 1 Test item as presented to the participants

An overview of the categories with inclusion and exclusion criteria and frequency of each category occurrence can be found in Table 2. To understand how sociodemographic characteristics may predict the evocation of the victimising category, the present project focused only on victimisation category evocation in the further analysis. Mean importance ratings of victimisation category occurrence were created. The exclusion of mean importance ratings that equated with zero was considered. However, subsampling the sample population in this way could have led to an overfit model that performs poorly on out of sample data.

In order to gain statistically valid and concise regression models, sociodemographic characteristics of the recruited population were eyeballed. Initial analyses indicated that some sociodemographic characteristics tapped onto the same underlying theoretical construct and needed recoding. High Cronbach’s alpha values of .82 were found for the victimisation category evocation of US Army Iraq Veteran (M = 2.03 [SD = 1.34]) and US Army Afghanistan Veteran (M = 2.19 [SD = 1.35]). Also, the independent variables ‘Attitudes towards the US deployment to Afghanistan’ (M = 1.89 [SD =.36]) and ‘Attitudes towards the US deployment to Iraq’ (M =1.93 SD =.32]) had a high Cronbach’s alpha value of.91. These variables were recoded by averaging and adding means. A list of the dependent and independent variables that were entered into the multiple linear regression model can be found in Table 3.

A preliminary G* Power Analysis52 suggested that a sample size of 79 participants would be adequate for a multiple linear regression with 13 predictors. Therefore, the recruited population of 245 participants was sufficient. A multiple linear regression model was computed after checking the assumptions of linearity, absence of multivariate outliers, absence of multicollinearity and equality of covariance matrices.

With acceptable measures of autocorrelation (Durbin Watson = 2.19), the multiple linear regression model indicates that evocation of the victimisation category is significantly predicted by sociodemographic factors; F (13, 244) = 2.934, p =.001. The variance in the victimisation category evocation explained by the sociodemographic characteristics was medium (14.2%).53 The multiple linear regression model suggests that the independent predictor ‘social distance to Veterans’ (tolerance =.514; VIF = 1.93) significantly predicted the evocation of the victimising category with those being closer to veterans exhibiting lower levels of victimisation category evocation (cf. Table 4). All other independent variables had no significant effect on the evocation of the victimising category.

Table 2. Category definition, examples & frequencies

| Category name | Definition | Examples | Frequency for US Army Iraq Veteran | Frequency for US Army Afghanistan Veteran |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimisation | Associations that refer to suffering from illnesses | PTSD Crippled Maimed | 203 (27.61%) | 246 (33.45%) |

| War | Associations, conceptualising the term ‘war’37 | War Destruction Death | 188 (25.58%) | 162 (22.04%) |

| Heroisation | Associations relating to superiority and heroism; Descriptions describing looking up to veterans | Heroic Bravery Saviour | 161 (21.9%) | 175 (23.81%) |

| Branch of Service | Reference to a group within the military; or membership within this group |

Army Soldier Military | 53 (7.22%) | 38 (5.17%) |

| Reference to US nationality | Associations that refer to US in-group belonging, national inclusion | One of us Ours US | 30 (4.09% | 28 (3.81%) |

| Political motives for deployments | Naming politicians and political reasons for the deployments | Bush, Oil wars Kill Saddam | 29 (3.94%) | 25 (3.4%) |

| Age | Associations to age and levels of experience | Young Rookie Old |

29 (3.94%) | 25 (3.4%) |

| Physical description | Physical description of a person | Tall Beard Short hair |

21 (2.86%) | 19 (2.58%) |

| Other | Associations that did not fit any category | ? Mountains Don’t Know |

15 (2.04%) | 9 (1.21%) |

| Job/occupation | Associations which refer to jobs, being employed and descriptive synonyms of these aspects | Job Professional Employed |

6 (.82%) | 8 (1.07%) |

In conclusion, the results suggest that victimising sentiments may be generally prevalent in characterisations of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, though particularly prevalent if those with little social contact veterans characterise US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans.

Study 2: Methods

To examine rationalities and individual reasoning processes that may underlie the victimisation of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans and to understand how social contact to veterans may impact the victimisation of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, an interview study was conducted.

Participants

A sample of 20 civilian participants who self-identified with having none or close social contact with US Army Iraq or Afghanistan veterans were recruited via snowball sampling. Specifically, study one’s ‘end- survey page’ provided the researcher team’s email address, asking the participants to express their interest if they wanted to partake in the interview study (Study 2). Of those who expressed interest, 10 participants who stated to have no contact with US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans on the demographic survey page, and 10 participants who stated to have close social ties to US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans (i.e. father, spouse, close friend) were invited. The total sample of 20 participants was collected in accordance with the sample size guidelines for thematic analysis, suggesting a range between 20 and 30 interviews.54 Following the completion of 20 interviews, the researchers found thematic saturation was achieved,55,56 meaning that after 20 interviews, a point was reached where no new concepts emerged from the interviews. An overview of the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics can be found in Table 5.

Table 3. List of dependent and independent variables

| Variable name | Classification |

|---|---|

| US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veteran Victimising Category Evocation | Continuous Dependent Variable (low to high category mean category importance and evocation) |

| Gender | Binary Independent Variable (male/female) |

| Age | Continuous Independent Variable (low to high age) |

| Education | Continuous Independent Variable (low to high levels of formal education) |

| Nationality | Binary Independent Variable (US vs other) |

| Ethnicity | Binary Independent Variable (Caucasian vs other) |

| Religion | Binary Independent Variable (Christianity vs other) |

| Opinion about the US Armed Forces | Continuous Independent Variable(low to high levels of appreciation) |

| Opinions about the US deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan | Binary Independent Variable (support vs opposition) |

| Social distance to US Army Iraq or Afghanistan Veterans |

Continuous Independent Variable (little to greater levels of social distance) |

| Social Distance to the US Military | Continuous Independent Variable (little to greater levels of social distance) |

| Time since residing in the US | Continuous Independent Variable(short to long time spent in the US) |

| National Pride | Continuous Independent Variable (low to high levels of national pride) |

| Political Opinion | Continuous Independent Variable (left [i.e. Democrats/Liberals] to right wing [Conservatives, Republicans]) |

Table 4. Coefficient scores of significant predictors

| Significant predictor | Unstandardised coefficients B [SD] | Standardised coefficients b | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social distance to veterans | -.29 [.78] |

-.31 | -3.66 | <.001 |

Table 5. Overview of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics

| Social distance | Age range | Education | Gender | Ethnicity | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No contact | 55+ | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P1-NC |

| No contact | 55+ | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P2-NC |

| No contact | 55+ | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Caucasian | US-P3-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P4-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | South-East Asian | US-P5-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | South-East Asian | US-P6-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | South-East Asian | US-P7-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Asian | US-P8-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Above A levels/ High school diploma | Female | Caucasian | US-P9-NC |

| No contact | 18–34 | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-10-NC |

| Close contact | 55+ | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P11-CC |

| Close contact | 55+ | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P12-CC |

| Close contact | 55+ | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Caucasian | US-P13-CC |

| Close contact | 35–54 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Turkic | US-P14-CC |

| Close contact | 18–34 | Below A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Caucasian | US-P15-CC |

| Close contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P16-CC |

| Close contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Black | US-P17-CC |

| Close contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Caucasian | US-P18-CC |

| Close contact | 18–34 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Male | Caucasian | US-P19-CC |

| Close contact | 18–4 | Above A Levels/ High school diploma | Female | Caucasian | US-P20-CC |

Materials and procedure

To understand how social contact with US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans may relate to holding victimising characterisations, the researchers decided to employ a semi-structured interview schedule. The interview schedule was structured in three subsections: free narratives, clarification prompts and theory-guided questions. In this sense, Study 2 was conducted to corroborate the findings of Study 1 in a qualitative setting and so to examine underlying rationalities of victimising perceptions. After the participants declared informed consent, they were encouraged to speak freely about their perceptions of Iraq and/or Afghanistan Army veterans in section one of the interview (‘When you think of US Army veterans who were deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, which thoughts come to your mind?’). The second section of the interview consisted of follow-up probes that encouraged the participant to elaborate on the information that was previously given (i.e., ‘You mentioned “courageous”. What do you mean by that?’). In the third section, specific questions attempted to probe into how participants developed their opinions about veterans (i.e., ‘What do you think about how US Army veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan are represented in newspapers?’). The interview questions were piloted and trialled before the 20 participants were interviewed. The interviews were audio-taped and anonymised during transcription. After the transcripts were sent to participants for checking, a inductive thematic analysis5,57 was conducted.

Data analysis

Following the transcription of the qualitative data, the transcripts were repeatedly read to become as intimate as possible with the accounts. Initial ideas about key topics and potential themes were noted using NVivo 12. The data was then reread and reviewed to identify potential key themes that emerged repeatedly. At this stage, the data was coded by categorising interview extracts. This allowed the identification of connected thematic properties that, drawn together, highlighted how social distance may impact perceptions of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans.

Study 2: Results

The findings suggest that social distance towards US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans mitigates the victimisation of veterans. Essentially, those who did not know a US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans equated deployments with combat experience. Therefore, veterans who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan as part of the US Army were associated with front-line fighting. This was considered to entail high levels of stress, as front-line fighting was understood to necessarily involve committing and witnessing violent actions and atrocities. In conclusion, participants who did not know US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans characterised a generic veteran population that suffers from inevitable mental health problems.

In contrast, participants who identified a US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veteran as belonging to their social circle explained the emergence of mental health problems by drawing on individual differences. Here, participants rationalised their characterisation of veterans by drawing on their individual experiences with veterans. Therefore, mental health problems were considered a possible but not necessary consequence of deployment. The following presents these findings by outlining extracts from the narratives.

Participants with close social contact to US Army Iraq or Afghanistan Veterans

All 10 participants with close connections to US Army veterans who returned from Iraq and Afghanistan discussed veterans possibly suffering from service-related mental health problems such as PTSD. However, the development of mental health problems was considered not exclusively related to military experiences but to traumatic experiences more generally. For example:

US-P11-CC: ‘It’s [mental health problems] not veteran specific […], if anybody experiences a trauma, they had a head injury, or something has really shook their core, they won’t be the same person anymore. No matter if it was war, if it was a car accident. […] They are all people with different experiences cause they have seen a whole bunch of different stuff, so they just try to deal with their experiences.’

This quote exemplifies how mental health problems were considered a possible but not necessary outcome of deployment. Instead of associating mental health problems exclusively to experiences encountered during the deployment, the trauma that was considered to cause mental health problems could happen in the civilian or the military context. This perception was shared in all 10 participants with close contact to US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans and was based upon educated conceptualisations of the deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. Specifically, due to their social ties, the participants knew about the soldiers’ different roles in Iraq and Afghanistan, not necessarily involving face- to-face fighting and combat experience. Therefore, the participants with social ties to veterans held a more nuanced and realistic conceptualisation of the US deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan:

US-P14-CC: ‘In the news, veterans are often pictures as hostile, unpredictable, war-weary, suffering from PTSD …. just a very stereotypical angry veteran. But in reality, many of those who have been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan didn’t actually see any fighting – like supply chain specialists, counsellors, cooks or Army chaplains. They are normal people, doing normal jobs. But I think they are just seen in these stereotypes. And I think that’s bad cause this makes them being pushed out and not perceived as normal people.’

Therefore, while combat experience was characterised as a possible part of a deployment, the participants did not equate deployment with face-to- face fighting. In this sense, veterans were considered to have completed occupational requirements. Deductive social labelling and definitions of a ‘veteran person’ who belong to a different societal category are therefore fundamentally rejected. This type of ‘othering’ commonly practiced by media, was perceived to communicate victimising sentiments, suggesting that veterans do not fit within the norms of society. For example:

US-P18-CC: ‘I think veterans need to be treated like normal people. […] Cause when you gonna throw that stigma on them, it is hard to find for them what they are when they are not in the military. Cause my dad [US Army Iraq veteran], he has really stressful days at work and, like normal people, he gets anxious. And I’ve heard his co-workers say: “Oh he’s just having an anxiety attack – PTSD, he’s a veteran.” No, he is having an anxiety attack cause he has a really stressful day! And… maybe it’s triggered by a trauma from Iraq, but anybody could have had a trauma. You don’t need to be a veteran to have a trauma!’

This quote illustrates how veterans are automatically related to mental health problems and stigmatising attitudes. Even if the veteran responds adequately to contextual requirements, this response is perceived to deviate from a societal ‘norm’ and ascribed to the veteran’s military experience. In this sense, ‘othering’ the veteran by constructing and labelling veterans as a social category comprises negative and victimising sentiments. However, contact with veterans diminished the extent to which veterans are victimised as those with closer ties to veterans rejected societal notions about veterans, exhibiting more knowledge about veterans and their deployments.

Participants with no contact to US Army Iraq or Afghanistan Veterans

Essentially, all participants with no social ties to veterans based their conceptualisations of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans on secondary sources such as media. Here, the predominant representations of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans witnessing or committing violent actions justified victimising perceptions of veterans. For example:

US-P2-NC: ‘I have read a book, I forgot which one it was, it was about a soldier in Iraq. So, they set up something like an outpost. And every few days there were raids and they pretty much saw their friends dying next to them, so I’d guess this is pretty traumatizing – to watch people getting killed next to you. […]And you just stand there, watching them. It’s really a tragedy cause it happens to young persons. I just can’t imagine it – it has to be so hard to do that. Definitely traumatizing.’

This quote exemplifies how representations of US Army Iraq, and Afghanistan veterans in media influence individual perceptions and conceptualisations of veterans. Due to the lack of personal experience with US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, the storyline—even if fictional— ultimately defines what it means to be deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Therefore, conceptualisations of the deployments become highly stereotypical with soldiers ‘facing death’ (US-P1-NC) and ‘fighting on the front line every day’ (US-P7-NC). This is considered to cause constant stress and trauma from which veterans retrospectively suffer. For example:

NC-P4-NC: ‘I don’t know anyone or veterans from there. But I know about PTSD and they are probably on edge a lot. If you are in a warzone, you are just constantly on edge. So, I feel if you are under intensive stress over such a long period in time, you cannot let go of it. […] I guess it is like having every week tests in school. When I graduated I was like – I am done with tests – I had nightmares, waking up screaming, so I was like: Wait, I don’t have any tests anymore. If you have been under stress for a while, I think it is just hard to let go.’

Here, the participant anticipated the veterans’ necessarily traumatising experience and tried to make sense of it by relating it to own experiences. Specifically, conceptualisations of the horrors of war were considered permanently damaging to the veteran. Worry and distress in the participant’s own life served here as a frame of reference to understand the anticipated mental health problems related to stress caused by battlefield exposure. Besides high levels of stress, the veteran’s experience with violence and front-line fighting were deemed to cause mental health problems. Here, all veterans were considered to have witnessed atrocities and committed violent actions. For example:

US-P6-NC: ‘Every veteran did it [killing]. I can’t imagine how it is to go through all that, to kill someone, even if they are terrorists. I can’t get my head round it. And I read a lot about PTSD of people who experienced war and tragedy. So, I am sure that there is that aspect and that there is a lot of things that are gonna trigger that memory. And I am sure there are a lot of people who have a physical reaction, breaking down, because of that. And that is probably very hard and probably very hard for their families to deal with as well.’

This quote exemplifies how mental health problems that veterans experience may be justified. Essentially, all veterans were considered to partake in violent actions, such as taking a person’s life, during their deployment, with memories associated to these actions haunting the veteran post-service. Therefore, attributions of mental health problems were based on understanding violence and violent actions as inhumane, as exemplified in the following quote:

US-P-1-NC: ‘I mean killing is unnatural and unnormal and humans have a lot of empathy – taking a human life is ridiculous. Even if it is in a sense very brave of them cause they were doing it counterterrorism, in some ways it is the only way – to kill them I guess. But someone who is actually doing that – it is still a human life that you are taking, And, even if it is the right thing – ultimately – you’re still responsible for cutting off their life stories and I think this is still a very hard thing to watch, to actually do. It’s damaging.’

While killing is considered necessary at times and justified in special circumstances, it is conceptualised as ultimately damaging. This also outlines the sacrificial aspect associated with veterans. Veterans willingly committed what was considered to be permanently damaging in order to protect US society. Therefore, the victimisation and heroization of veterans were highly intertwined.

US-P3-NC: ‘I’d think that having to take someone’ life will haunt veterans, especially if they had to do it more than once. […] And I respect that, I am thankful for it. I don’t like killing, don’t think it’s the right thing to do. But it’s just necessary… sometimes – unfortunately. And I am thankful that I did not have to do it.’

This quote exemplifies the controversial attitude towards killing that 8/10 participants with no contact to veterans held. While veterans were considered victims of committing lethal actions, they were also appreciated and heroised for this as it saved the participants from taking part in warfare. In this sense, veterans were considered to sacrifice their mental health by committing violent actions for the participant and the US more generally.

In conclusion, attributions of mental health problems were not based on reflections of critically evaluated, objective information. On the contrary, understanding veterans as damaged individuals was rooted in the participants’ highly emotional responses to experiencing existential threats and committing violent actions.

Discussion

The present explorative study examined which factors may contribute to elevated victimisation scores in characterisations of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans and why. The mixed-method approach produced the following key findings, answering the paper’s research question:

Which sociodemographic characteristics predict higher victimisation scores?

The multiple linear regression with the victimisation category evocation as a dependent variable and sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables (gender, age, education, nationality, ethnicity, religion, opinion about the US Armed Forces, opinions about the US deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, social distance to US Army Iraq or Afghanistan Veterans, social distance to the US Military, time since residing in the US, national pride, political opinion) was significant. However, only ‘social distance to US Army Iraq or Afghanistan Veterans’ predicted victimisation category evocation significantly, with those closer to US Army Iraq or Afghanistan Veterans scoring lower on the victimisation category evocation.

Why do the sociodemographic characteristics outlined in Study 1 predict higher victimisation scores?

The results of the qualitative interview study suggest that both cohorts, those who know and those who do not know US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans had little knowledge about how mental health problems evolve. However, participants who know US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans had a more nuanced understanding of the deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan and of what those who have been deployed did. In contrast, individuals who did not know US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans based their conceptualisations on secondary sources such as media. Here, representations of veterans were internalised that characterised veterans as suffering from their deployment experiences. These representations of veterans as victims remained unquestioned and were justified by individual understandings of deployments that were equated with battlefield exposure and front-line fighting. Additionally, the present findings suggest that victimising and heroising sentiments may be highly intertwined. While violence and war were considered to be occasionally unavoidable but necessarily damaging, veterans were appreciated for their willingness to sacrifice their life, or, at least, their mental health. However, as those who knew US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans had a more explicit understanding of the different roles and jobs entailed in a deployment, veterans were neither arbitrarily considered as heroes or victims. Instead, deployment was perceived as an occupational requirement that may, but not necessarily, cause trauma. Therefore, veterans who returned from deployment were neither heroised nor victimised and thus not stigmatised.

The present findings are aligned with previous research suggesting that members of the US public may hold an implicit bias and stereotyping attitudes towards veterans.2,3,15 The present research extends previous knowledge by examining which sociodemographic characteristics predict the victimisation of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans and why they do so. Therefore, the present findings contend with research suggesting that difficulties in veterans’ transition may be at least partially accounted for by negative, victimising public perceptions and anticipations of mental health problems.2,15

Mental health difficulties may not be the only reason why veterans suffer from an increased risk of suicidal ideation, unemployment, alcohol or substance abuse and homelessness ().4-12 Instead, negative and victimising portrayals of veterans in the news and media may contribute to implicit stigmatisation and social exclusion of veterans. This, in turn, may impact the reintegration of veterans into civilian society. However, in contrast to previous research, no evidence was found that age, ethnicity, social class, political affiliation and gender influence attitudes towards former Service Personnel.29,31,32 It may be concluded that these sociodemographic characteristics may therefore only impact on positive perceptions, not victimising perceptions of veterans.

Although the results have provided a thorough examination of the victimisation of US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, a number of caveats need to be taken into consideration. One limitation addresses the homogeneity of the quantitative study’s sample cohort. The cohort comprised a high proportion of white, well-educated females in their mid-twenties. Thus, unlike previous research with representative samples3 the present findings cannot be considered representative for the US public. Many of the individuals were still children when the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan began, and so may not have been familiar with the arguments for and against interventions at the start of the conflicts. It may be interesting to compare an older group who were adults at the start of the conflict to see how they may differ from this sample in their beliefs.

The second limitation concerns the selection of associations for analysis. Only an average of 30.53% of the associations to the stimuli terms ‘US Army Iraq Veteran’ and ‘’US Army Afghanistan Veteran’ were utilised for the analysis. However, the limited number of associations that directly relate to the victimisation of veterans can be explained by the highly explorative and open-ended nature of the study. The aim of the study was to examine which associations participants provided without given answering categories; to examine these original associations. Therefore, the benefit of assessing original associations that the participants provided outweighed the limitation of including only a limited number of associations.

Lastly, the qualitative study’s method of analysis remains subject to scrutiny. Thematic analysis would have allowed integrating a range of analytic options and multiplexed perspectives. By examining themes that evolved from the participant’s answering patterns, it may be possible that other, more implicit themes have been overlooked. This may be particularly the case for the present study, as the focus was placed on examining victimising sentiments in relation to contact with veterans. In conclusion, the discussion and interaction of thematic properties may have been presented in a simplified fashion, balancing the presentation of in-depth explanative and in-breadth explorative information. While the qualitative and quantitative studies could have been elaborated on, the present findings provide the first overview of an under-researched area to date. Future research may want to examine to which extent the present findings may be replicated with veterans from other deployments or non-combat veterans. This would allow to compare and contrast perceptions of veterans, providing a holistic picture of the US public perceptions of their veterans.

Conclusion

The present study suggests it may be necessary to close the civil-military gap to improve the reputation of veterans. Therefore, the present findings suggest that civilians may need to know US Army Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans and see them as individuals who successfully accomplished occupational requirements. This would allow dissociating veterans from heroising and victimising sentiments, which are highly intertwined concepts. Also, the predominantly negative and victimising portrayal of veterans in news and media is counterproductive. In addition, it may be helpful to improve the public’s understanding of the development of mental health disorders. Members of the general public need to know that traumatic situations can be experienced in the civilian and military context. This may have problematic consequences for veterans as implicit mental health problems can lead to stereotyping and stigmatisation. How to explain and educate the public about veterans and the tasks they have accomplished tasks in a complex and contested moral space is an important area of public discourse that deserves more attention.

Corresponding Author: Rita Phillips, r.phillips5@rgu.ac.uk

Authors: R Phillips1, H Albanesi2

Author Affiliations:

1 Robert Gordon University, Applied Social Sciences, Aberdeen AB10 7QB

2 University of Colorado – Sociology Colorado Springs