Ian Howie-Willis

Abstract

Two sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) marched in lockstep with the Australian Army in most, if not all, its overseas campaigns during the twentieth century. Gonorrhoea and syphilis, bacterial infections spread most commonly through sexual intercourse.

This article illustrates through reference to the Australian Army’s major overseas deployments; from the Boer War at the beginning of the century to the war in Vietnam, which ended in 1975.

The primary purpose of the paper is to demonstrate the scale of STD infections in the Army’s overseas deployments. There is, of course, a ‘human’ or ‘sociological’ aspect as well.

When investigated, every STD episode can be seen to be a little disaster of its own; a mini-tragedy for the soldier contracting the STD, for the person who most often transmitted it to him and, beyond them, for their families.

Subsequently, there is the medical aspect: the measures taken by the staff of the Army Medical Service to prevent the STDs and to treat those who contracted STDs.

Significant though the sociological and medical aspects of the Army’s experience of STDs are, this article does not dwell on them. Instead, the focus is statistical, showing the large scale of the STD problem during the Army’s overseas deployments of the twentieth century.

Key terms: sexually transmitted infection (STI), sexually transmitted disease (STD), venereal disease (VD), gonorrhoea, syphilis, twentieth century, Australian Army

Introduction: semantics of the ‘sexually transmitted infections’

The term sexually transmitted disease or STD became the preferred term among medical professionals during the mid-1970s. It replaced a previous collective term Venereal Disease or VD, used by previous generations. VD was part of common parlance in all English-speaking societies until the wish for a less values-laden phrase pushed doctors specialising in sexual health—itself a neologism— towards a semantic shift. Sexually transmitted disease has since been replaced by ‘sexually transmitted infection’ (STI) in the early twenty-first century.1

Both STI and STD are euphemisms, ‘culturally sensitive’ terms for what are often distressing, debilitating and embarrassing diseases that can be passed on to the innocent partners and children of sufferers. A further reason for changing the terminology was that historically VD referred predominantly to syphilis and gonorrhoea, whereas STI includes conditions such as chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, chlamydia, HIV-AIDS and other infections transmitted sexually.

In this article, the older term VD will be used generally to reflect the accustomed term used at the time of most of the Army’s campaigns and deployments discussed.

Similar semantic changes have occurred in the terms used for medical practitioners specialising in the STIs. Until the mid-1970s, such specialists were known as venereologists and their specialisation as venereology. They later became known as sexual health physicians and their field of expertise as sexual health. Whatever the profession might call itself at any time, ‘pox doctor’, a derogatory 17th century term, remains extant, at least colloquially— as in the expression ‘all dressed up like a pox doctor’s clerk’.2

The venereal diseases

The Australia Army, like most others, has often suffered high incidences of VD, which for much Australian military history has meant principally gonorrhoea and syphilis, rather than any of the other STDs; of which there are least 14. Gonorrhoea and syphilis have always been the most common forms of VD in the Army and those causing the most concern.

There were various reasons for this concern, including:

- Until the advent of penicillin in the mid-1940s, both diseases were difficult to treat and cure. Approximately six weeks in hospital, undergoing daily treatment was the standard regimen. That meant a huge diversion of scarce resources to treat those infected.

- The time required for treatment entailed a huge loss of trained labour resulting in enormous costs for the replacement of those in hospital undergoing treatment.

- VD was essentially self-inflicted. For that reason, it caused much annoyance among Army commanders, who consequently saw it as a disciplinary as much as a medical matter.

- VD also exasperated the medical officers, who generally regarded their obligation to treat it as a diversion from their essential role in treating combat injuries and other infectious diseases.

- Those who suffered VD were the husbands, sons and brothers of Australian women, who would have been aghast to know that in many cases their men spent much of their time overseas in hospital being treated for diseases that were so taboo they could not be discussed around the family dinner table.

- There was a fear that soldiers returning from overseas service might bring VD with them and spread it through the Australian community.

Gonorrhoea

Gonorrhoea is caused by the gonococcus, a motile diplococcal bacterium, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infection sites are typically the areas of sexual contact—the soft, moist membranes of the penis, vagina, anus, rectum, throat and eyes. The gonococci move through bodily fluids by twitching their hair-like appendages and attaching themselves to tissue, which they then infect.3

Figure 1: Electron microscope image of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the gonococcus causing gonorrhoea. (Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

In both men and women, gonorrhoeal infection commonly spreads along the genital and urinary tracts. The gonococci cause acute urethritis (infection and inflammation of the urethra), usually producing a discharge of pus from the urethra.

Before penicillin, the standard treatment was twice-daily irrigation of the urethra and bladder with a combination of powerful antiseptics. These included Argyrol (a silver nitrate compound) and Benetol (b-napthol, also called hydroxynaphthalene, a toxic compound chemically similar to phenol or carbolic acid, a corrosive antiseptic). These compounds were injected into the urethra and bladder and had to be retained there for several hours.The treatment was prolonged, messy, uncomfortable and embarrassing. It was also lengthy as a five to seven-week hospital stay was usually required before a patient was free of symptoms.

Figure 2: Metal syringe, with curved metal urethral catheter, used for irrigating the urethra with antiseptic compounds. (Source: Wellcome Images, an online source of the Wellcome Trust.)

Syphilis

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochaete or small spiral-shaped bacterium.4 Like gonorrhoea, it can be congenital; passed from mother to unborn baby.

Syphilis acquired through sexual intercourse goes through a series of phases that may extend across decades. The first of these is an incubation period lasting an average of three weeks, during which no symptoms are apparent. The second stage, known as primary syphilis, is when the first symptom appears—often a chancre or hard, usually painless ulcer at the infection site .If left untreated, the chancre disappears.

Secondary syphilis subsequently appears, from two to four months after infection. The most common symptom is a rash of red, flat lesions occurring over the whole body as the spirochaetes multiply and spread via the blood to the skin, liver, joints, lymph nodes, muscles, brain, bones and mucous membranes of the mouth and throat. The rash heals within several weeks and the disease will enter a dormant phase that may last for many years.

Tertiary syphilis may appear in 30–40% of untreated individuals, in whom the spirochaetes reactivate, multiply and spread throughout the body. As they do, they irreversibly damage and eat away the parts of the body they attack, including the heart, eyes, brain, nervous system, bones, joints and facial appendages. The result is often gross disfigurement, insanity and then death.

Figure 3: Pictomicrograph of spirochaetes of the Treponema pallidum species. (Source: US Centres for Disease Control)

Before penicillin, treatment was via intramuscular injections of highly toxic arsenic and mercury compounds. The side effects included severe mouth ulcers, the loss of teeth and kidney failure. Because of the toxicity of the treatment, the death of the patient was always a risk. In the US Army, patient mortality of less than one per cent was considered ‘good’. A cure could not be guaranteed; and so until penicillin the old adage remained true—‘An afternoon of Bacchus, an evening of Venus and a lifetime of Mercury’.

Infection in Australia

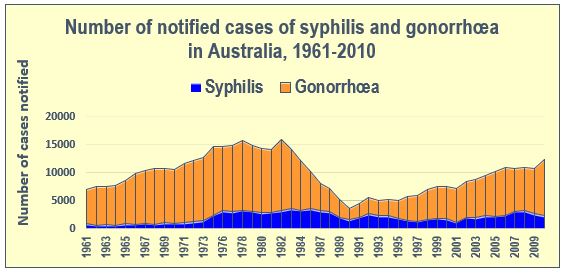

The number of cases of gonorrhoea Australia-wide peaked at 12 352 in 1978 and syphilis at 3 594 cases in 1986.The incidence of both diseases subsequently fell away but then began climbing again. Figure 4 indicates the changing epidemiology of both diseases.5

Figure 4: Number of notified cases of syphilis and gonorrhoea in Australia, 1961–2010 (Source: Australian Yearbooks, Canberra, Australian Bureau of Statistics, years 1961–2010)

Epidemiologists and venereologists have debated the reasons for these trends. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacteria responsible for gonorrhoea and syphilis was one factor. Changing societal mores were another. Generations grown indifferent about the risks of casual sex and less the social and religious sanctions against promiscuity were probably unconcerned about the stigma that had blighted the lives of gonorrhoea and syphilis sufferers in earlier generations. The rising incidence of the Army’s ‘traditional’ STDs among the general Australian population is consequently of great concern to public health authorities.

Pre-Federation deployments

The incidence of the VD in the overseas conflicts to which the pre-Federation Australian colonies sent troops is unknown. These were the New Zealand land wars of 1845–46 and 1860–72, the Sudan campaign in 1885, the South African (or Anglo- Boer) War of 1899–1902 and the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900–1901.Given the high rates of VD infection among Australian troops in later overseas deployments, it would be surprising if VD had not been a concern for the military-medical officers in these earlier conflicts as well.

The best documented of the late colonial era conflicts was the South African War, to which the colonies and then the new Australian Army sent contingents. The various histories of the war, both British and Australian, deal at length with the organisational arrangements made for the various field ambulances and stationary hospitals set up to treat injured and sick soldiers. The only infectious diseases discussed in any detail are two other historical scourges of armies—dysentery and malaria. VD never rates a mention.

For reasons unknown, perhaps the prudery of the era, VD is ignored in official accounts of the South African War. Neither the 300-page report of the 1903 British commission of inquiry into the war6, nor the 395-page 1904 official British government report on the medical arrangements for the war by the Army’s Surgeon-General7 include any reference to VD. Nor does the six-volume quasi-official British history of the war published by The Times newspaper of London.8

Despite the official silence on VD, we might surmise that some of the Australian troops arriving in South Africa either brought VD with them, acquired VD in Africa and took VD back home after their departure, as this was certainly the situation during the next war 12 years later—World War I.

The most recent Australian historian of the war, Craig Wilcox, has suggested the possibility that some Australians might have contracted VD during their South African service. Wilcox describes the Australian colonial contingents arriving at the port of Beira in Mozambique, from where they caught trains into South Africa. The Australians generally thought the town ‘immoral’; but many, appreciating the ‘free-flowing liquor’, went on ‘drunken sprees’.9 Did that lead to VD? Wilcox does not say, but the nexus between inebriated soldiers, readily accessible and cheap prostitutes and high rates of VD would be a common theme in the Army’s subsequent overseas deployments during the twentieth century.

Eventually the British Army did publish the VD figures for the South African War, but not until 1931 in the statistical volume of the official medical history of World War I. The 19,127 VD cases treated during the war amounted to 4.7 per cent of all 404,126 hospitalisations for disease.10 That many VD cases among the British troops strongly suggests that among Australian soldiers, too, VD was also problem for their medical officers.

Australian soldiers’ VD infection rates during World War I

The first conflict in which the Australian Army medical units kept comprehensive medical statistics was World War I. Officially there were 181 separate ‘disabilities’ which caused soldiers to be ‘rendered unfit, temporarily or permanently, for service’ in the Army. VD was among the most common of these.11

The Army’s losses to VD in World War I were enormous. An estimated 63 350 VD cases occurred among the 417 000 troops of the 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF). That is, one in seven of the soldiers who joined the AIF contracted VD at some stage of the war. That many soldiers was the equivalent of three infantry divisions. Given that the average VD treatment time was six weeks, the high number of VD infections effectively meant that for six weeks of the war the AIF commanders had lost three infantry divisions. Little wonder that VD perturbed them greatly!

Figure 5: The Isolation Hospital at the Broadmeadows Army Camp, World War I, possibly 1914–15. Little is known about this ‘lock’ hospital. It was probably a secure section of a larger camp hospital at Broadmeadows, established to manage contagious diseases such as measles, influenza, tuberculosis, meningitis and VD until specialised infectious disease hospitals could be established elsewhere. Note the 5-strand barbed-wire perimeter fence to prevent patients from absconding. (Source: Australian War Memorial, photograph no. H18401.)

Egypt in World War I

The first known VD epidemic suffered by the Australian Army occurred in Egypt. It began almost as soon as the 1st AIF arrived there for training in the months before the Gallipoli campaign.12

In 1915, the first year the Army spent in Egypt, 4 046 out of some 30 300 Australians, or over 13%, were admitted to hospital suffering from VD. The rates in Egypt remained high. In 1916, the rate was 14% of strength, and in the last full year of the war, 1918, it was 11%.

Figure 6: Soldiers (almost certainly staff) standing on the verandah of the X-ray and operating rooms of the No. 2 Australian Stationary Hospital at Moascar near Ismailia, Egypt, 1918. This hospital was the principal VD treatment centre for Australians serving in the Middle East. It was relocated several times, tending to move to where the troops were concentrated. (Source: Australian War Memorial, photograph no. B02450.)

Britain and the Western Front in World War I

The 1st AIF’s next VD epidemics occurred in Britain and on the Western Front between 1916 and 1919.13

Some 295 000 troops of the 1st AIF were deployed to the Western Front in France and Belgium during those years. In that time, Australian soldiers in the UK, France and Belgium suffered 584 248 disabilities requiring treatment by an Australian Army Medical Service unit. VD cases accounted for at least 48 880 of these, 22 265 in the UK and 18 165 in France and Belgium, i.e.8.4% of all disabilities. Expressed as a rate per thousand of overall troop strength, the Army’s VD ‘episodes’ amounted to 166 cases per thousand soldiers.

The total incidence of VD cases among Australian soldiers in the UK 1916–1918, 22 265, was 20% higher than the 18 165 cases in France and Belgium. The rate of VD infection in the UK was also appreciably higher than in France and Belgium. For example, in the middle year of deployment to the UK and the Western Front, 1917, the rate in the UK was 148 cases per thousand troops, whereas the rate in France and Belgium was 73 per thousand, only half the rate in the UK that year.

The main reason for the disparity in the incidence and rate of VD between the UK and France and Belgium was opportunity for infection. Soldiers in the UK were not currently engaged in combat; those on the Western Front were and consequently had less time in which to contract VD. The discrepancy effectively illustrates the Army venereologists’ saying that ‘the incidence of VD among soldiers is inversely proportional to their amount of combat’.

VD was not the most common affliction suffered by the AIF, at least on the Western Front. Respiratory tract infections were far more prevalent, amounting to 110 650 cases or 37.5% of disabilities. That was more than four times higher than the rate for VD. The higher figure for respiratory infections was hardly surprising considering that the AIF fought amid the cold, rain and mud of three northern European winters, following which the worldwide 1918–19 wave of pandemic influenza swept over the troops.

Figure 7: Administrative headquarters of the No. 1 Australian Dermatological Hospital, Bulford, Wiltshire, April 1919. The hospital was the principal VD treatment facility for 1st AIF soldiers in Britain. Although a grim, depressing amenity for patients and staff alike, it undertook effective medical work. In its peak year of activity, 1918, it managed 9 404 patients. (Source: Australian War Memorial, photograph no. D00456.)

The Australian Army’s VD infection rates during World War II

During World War II, the 2nd AIF again suffered high VD infection rates. In the Middle East, the rate was 48 cases per thousand troops in 1941, the peak year. That was only two-thirds (65.7%) the rate among the 1st AIF on the Western Front in World War I; however, the Army’s commanders and medical officers agreed it was nevertheless ‘far too high’.14

Later in World War II, the Army’s VD infection rates were appreciably lower than in the Middle East. In the South West Pacific theatre, mainly the archipelagos to Australia’s north, the highest rate was only eight per thousand in 1945 or 0.08% of strength. Such a low rate reflected a lack of opportunity for infection.

The rates among troops in Australia were higher, for example 19 per thousand in 1942, which was only around half the rate in the Middle East the previous year. Nevertheless, that figure caused ‘considerable anxiety’ that the troops would spread their gonorrhoea and syphilis into the general population.

An estimated 34 180 cases of VD occurred among Australian troops during World War II. This was only 52% of the 63 350 cases of the 1st AIF during World War I. How may such a disparity be explained? The answer is complex, but it can be reduced to the following factors.

There was greater awareness among soldiers of the risks, dangers and consequences of VD infection. This reflected the state governments’ enactment of legislation for controlling VD during the 1920s and 30s, their establishment of public VD treatment clinics, their anti-VD propaganda campaigns and the influence of the Commonwealth Department of Health in disseminating information about the diseases.

The Army vigorously promoted its ‘Blue Light’ Prophylactic Ablution Centres (PACs), i.e. units providing pre-emptive treatment for soldiers who had exposed themselves to the risk of VD infection.

The Army recruited specialist venereologists to staff its VD hospitals. Their availability to the ‘Blue Light’ PACs, and their training of the PAC medical orderlies, meant that the PACs functioned more efficiently than previously.

The availability of the ‘sulpha’ drugs, e.g. sulphanilamide, from the late 1930s.Such drugs were particularly effective against gonorrhoea, greatly reducing treatment times. Many soldiers contracting gonorrhoea treated themselves with sulphanilamide without reporting to Army medical units—and without consequently becoming ‘VD statistics’.

In the Middle East, where the 2nd AIF’s infection rates were the highest of the war, the Army introduced a system of controlled brothels in which the prostitutes were regularly examined for symptoms of VD.

Figure 8: Staff of No. 8 Australian Special Hospital, Kilo 89 Camp, Gaza Ridge, Palestine, December 1941. Left– right: Staff Sergeant D. McDonald, Lieutenant Colonel DB Loudon (the Commanding Officer) and Lance Corporal C. McHale. The 8th Special Hospital was the 2nd AIF’s main VD treatment centre in the Middle East 1940–1942. (Source: Australian War Memorial, photograph no. 100325.)

Australian VD rates in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan

The Army’s first post-war overseas deployment was to Japan, as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force. The deployment lasted for six years (1946–1952). In that time, 16 500 Australian military personnel served with the Occupation Force. The Australians’ VD infection rate during this time was extraordinarily high. The number of individual Australians who contracted VD was 4 768 or 29% of the Australians who served with the force. There were 7 350 separate VD episodes or cases, which means that 2 582 soldiers suffered more than one episode. The record was 12 episodes, which means that that particular soldier must have spent at least 192 days out of his one-year deployment in hospital being treated for VD.15

Figure 9: Japanese female civilian employees ironing clothes at the British Commonwealth Occupation Force base laundry, Hiro, Japan, June 1952. The Occupation Force was obliged to employ a large Japanese labour force. Many Japanese civilians worked at such bases and much fraternisation between the workers and soldiers occurred, even though it was officially discouraged. Inevitably, fraternisation contributed to high Australian VD infection rates; however, it also meant that infection was transmitted through the workers into the Japanese community. (Source: Australian War Memorial, photograph no. 147948.)

The overall infection rate 1946–1962 was 446 cases per thousand troops, near enough to an infection rate of 45%. These figures mean that the Australians in the Occupation Force have the dubious distinction of ‘scoring’ the Army’s highest ever VD rate.

How were the Occupation Force soldiers able to tally such a high rate? The answer partly lies in the destitution of the Japanese population in the immediate post-war years. The Australians Forces were deployed to the Hiroshima Prefecture, the most devastated and therefore the most poverty-stricken, region in Japan. Japanese culture had traditionally tolerated prostitution and consequently, many Japanese women resorted to prostitution to help their families survive their post-war deprivation and poverty. These Japanese prostitutes were usually infected with VD.

The other part of the answer lies with the soldiers themselves. Without a war to fight, the well-paid Australians had ample leisure, few recreational facilities and little to distract them from booze and sex, which usually went together. Pertinent here is the old Army venereologists’ adage that ‘Army VD rates are inversely related to the amount of battle activity’.

The Australian Army’s VD rates in Korea

The next major conflict to draw troops from Australia was the Korean War of 1950–1953.In the three years it lasted, some 17 000 Australian military personnel were deployed in Korea. They contracted VD at very high rates. The Australian rate, 386, was slightly above the overall Commonwealth figure but appreciably lower than the Canadian and New Zealand rates. However, comparatively ‘good’ that was, except for the recent Occupation Force in Japan, the rate was more than 2.5 times the previous ‘worst’, 148 in the UK in 1917.An estimated 4 110 Australian soldiers contracted VD while serving in Korea.16

Figure 10: Captain J. Bannerjee, a surgeon from India, examines a British casualty in front of the 60th Indian Field Ambulance reception tent, Korea, 1950. Assisting him are two 60th IFA orderlies while four others look on. The 60th IFA was the main early treatment centre for Commonwealth forces in Korea. The unit managed many Australian casualties. It also doubled as the main VD treatment facility for Commonwealth troops and, as such, it handled most of the estimated 4 110 cases of VD that occurred within the Australian contingent. (Source: Australian War Memorial, photograph no. HOBJ1894.)

Why was the rate in Korea so much higher than those in the First and Second World Wars? The high rates partly reflected the practice of sending the troops to nearby Japan for their recreation leave. As seen, prostitution at that time was commonplace in Japan and most prostitutes were infected with VD.As the official medical historian observed, resorting to prostitutes was ‘the normal reaction of young men spending five days’ leave in a big city, far from the hazards of war’.

The main factor, however, was the availability of penicillin. The widespread adoption of penicillin-based antibiotic drugs at the end of World War II had greatly lessened the burden of treating bacterial infections. In the case of gonorrhoea and syphilis, penicillin had obviated the previous messy, painful, protracted and toxic VD treatment regimens. Information about the efficacy of the new ‘wonder drug’ in rapidly curing VD filtered down to the level of the common soldier. Assured of a rapid cure, they were less concerned about contracting VD than soldiers in previous wars.

The Malayan Emergency and Australian VD rates

From 1955 to 1960, Australian soldiers fought with British troops on the Malayan Peninsula in a war known as the Malayan Emergency. The Emergency was essentially a Communist-led guerrilla war against British colonial rule and against the Malayan government that replaced it.17

As in the occupation of Japan and the Korean War in the recent past, the VD rates among the three Australian battalions successively deployed to Malaya were very high. The overall rate was 415 cases per thousand troops, or two-fifths of the soldiers sent to Malaya. An estimated 2 900 Australians serving in Malaya contracted VD.

VD rates in the Australian Army in Vietnam

A decade after the armistice in Korea, Australian troops were engaged in another and longer war, this time in Vietnam. The Australian involvement in the Vietnam War lasted for 11 years, from June 1962 until June 1973.The rates of VD infection were once again high. In the peak year for infection, 1967, the rate was an astounding 478 cases per thousand troops. The rate across all 11 years was 231 cases per thousand. An estimated 11 380 Australian soldiers contracted VD during service in Vietnam.18

The reasons for the very high rate in Vietnam were perhaps similar to those in Korea in the early 1950s.The ‘mix’ included a reduced fear of VD among troops with ready access to effective antibiotics; an abundance of cheap prostitutes; high rates of VD infection among the prostitutes; ample liquor in readily accessible bars that were almost always brothels as well; and the determination of virile young soldiers to ‘have fun’ during leave after the stress of front-line action. In Vietnam, there was also a reckless, hedonistic defiance, which the official medical historian of the war alluded to by writing that ‘the Australian servicemen displayed no inclination to exercise restraint or take precautions’.19

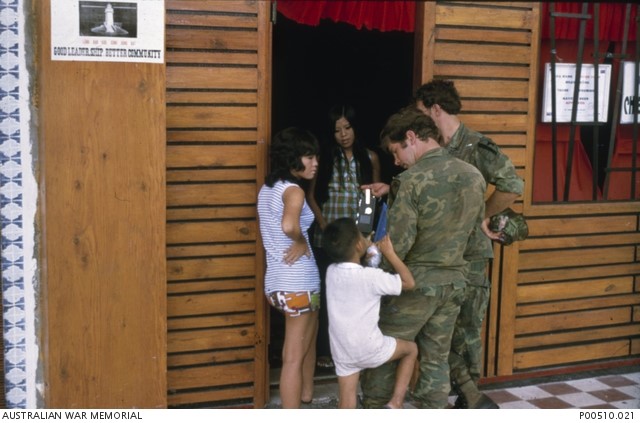

Figure 10: Bar girls in the entrance to the ‘Texas Bar’, Vung Tau, chatting with American soldiers as a Vietnamese boy claims the attention of one soldier. The bar, effectively a brothel, was also much patronised by Australians. Note the ‘Approved Premises’ sign (arrowed) in the bar window. This indicated that the bar girls had been medically examined and were purportedly ‘VD-free’. In reality, the ‘hostesses’ of the ‘approved’ bars often still contracted VD as they were commonly infected by the customers they serviced after their examinations. (Australian War Memorial, photograph P001510.021.)

In Vietnam, as in all the previous conflicts, the Army’s commanders and medical officers were concerned as much by manpower as by disciplinary, moral and medical considerations. A high VD rate has always meant a depleted fighting force because every soldier being treated in hospital for VD represented one less man available for duty. If the 11 380 troops were withdrawn from normal duties for just two days’ treatment—the average time for VD cases—then 22 760 ‘man-days’ or 62.4 ‘man years’ were lost in Vietnam. Another way of expressing the manpower cost of VD would be if the Australian force in Vietnam suffered 231 VD ‘casualties’ per thousand of strength, only 23% of the force would have been available for service throughout the year. Such a rate implied a large-scale reduction in military capability.

The STDs in the Army post-Vietnam

After the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 dozens of overseas deployments lay ahead of the Australian Army. They have included East Timor, Bougainville, the Solomons, Iraq and Afghanistan. If previous experience were any guide, such post-Vietnam deployments would have yielded a continuing number of STD cases, including both gonorrhoea and syphilis and other ‘newer’ STDs such as HIV-AIDS and chlamydia.

Little is known of the Army’s post-Vietnam STD infection rates. The dearth of data reflects what one senior Australian Defence Force (ADF) medical officer has termed ‘the confidentiality crisis’ generated by the HIV epidemic. Sensitivities over the confidentiality of STD data was such that from the 1980s few anonymised data sets existed, much less made accessible to historians.20

Vigilance over STD rates nevertheless remains a duty for the health professionals, military commanders and for individuals in the Armed Forces.

What measures did the Army adopt to reduce the incidence of its two ‘traditional’ diseases?

Over the 75 years this paper covers, the Army did everything possible to control and reduce the incidence of gonorrhoea and syphilis.21 At various times the Army commanders, administrators, medical officers and military police tried all of the following:

- Semi-criminalising the contraction of VD, notably by: (a) confining VD patients under guard to secure lock-hospitals; (b) stigmatising VD patients, e.g.by requiring them to use separate dining, ablution and toilet facilities); (c) treating VD patients in separate, isolated VD hospitals; (d) sending VD patients back to Australia in disgrace; (e) ensuring that the treatment regimens in the VD hospitals were harsh; (f) stopping the pay of VD patients while they were undergoing treatment; and (g) curtailing leave and other privileges of VD patients.

- Supervising soldiers’ off-duty time and behaviour to minimise their opportunities for fraternising or visiting brothels and picking up streetwalkers. Such measures included: (a) provision of sporting and recreation facilities; (b) declaring ‘red-light’ districts in towns frequented by soldiers to be out-of-bounds to troops; (c) military police patrols through such districts to round-up soldiers and send them back to camp; and (d) frequent bed checks after lights-out to ensure soldiers were in bed and not absent visiting prostitutes.

- Education and propaganda on the nature, causes and societal ramifications of VD infection, including: (a) lectures by chaplains on the moral aspects of VD infection; (b) lectures by Medical Officers on VD causes and prevention; (c) compulsory written examinations on the types, nature, symptoms and treatment of VD; and (d) anti-VD posters, pamphlets, films, information leaflets and articles in Army newspapers.

Regular medical inspections of the troops to check for telltale symptoms of VD infection.

Provision of free, well-publicised prophylactic measures, made available on a ‘no questions asked’ basis and preserving soldiers’ anonymity. These included: (a) issuing ‘Blue Light’ prophylactic kits containing condoms and antiseptic ointments to be rubbed into the genitals and surrounding areas immediately before and after sexual activity; and (b) conducting ‘Blue Light’ PACs at all major Army camps and in red-light districts frequented by soldiers. Ideally, soldiers visited the PACs as soon as possible after sexual contact so that their genitalia could be washed, irrigated with antiseptic compounds and dressed with antiseptic ointment.

Establishing venereological hospitals in Australia and the overseas theatres where Australian units were deployed. Staffed by specialist venereologists and trained medical orderlies, these hospitals provided treatment regimens that were the best available.

Regulating and punishing women accused of transmitting VD. Such measures included: (a) identifying the women who had been the source of particular soldiers’ infections, then locating them to insist on their treatment; (b) persuading civilian police to arrest and charge prostitutes, and have them convicted, imprisoned and compulsorily treated; and (c) removing from the vicinity of Army camps the ‘part-time’ and ‘amateur’ prostitutes who congregated there.

Authorising particular brothels and prostitutes to service Australian soldiers by issuing them with permits and regularly checking the for VD symptoms. In the Middle East in 1941-1942, and later in Vietnam, the Army effectively conducted its own Army-supervised brothels staffed by officially approved prostitutes.

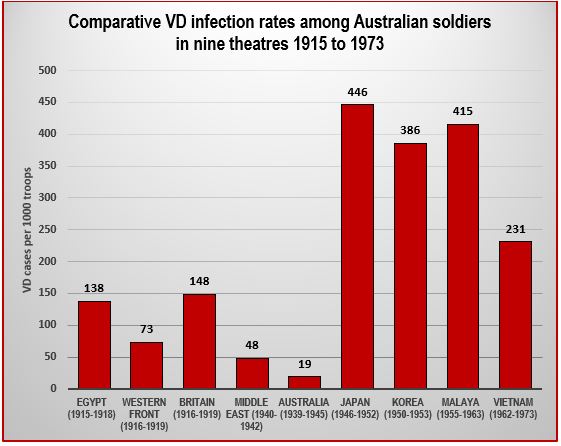

Education and propaganda on the nature, causes and societal ramifications of VD infection, including: (a) lectures by chaplains on the moral Figure 11 shows the estimated overall rate of VD infection per thousand of troop strength in nine theatres to which Australian troops were committed between 1915 and 1973.The great disparity between the pre-1945 and post-1945 rates reflects the impact of penicillin. After the introduction of penicillin, soldiers had little to fear from VD because treatment required only several days in hospital—in contrast to the pre-penicillin era when a VD infection entailed many weeks in hospital undergoing painful, hazardous treatment regimens.

Figure 11: Comparative VD infection rates among Australian soldiers in nine theatres 1915 to 1973

Figure 11 shows the estimated overall rate of VD infection per thousand of troop strength in nine theatres to which Australian troops were committed between 1915 and 1973. The great disparity between the pre-1945 and post-1945 rates reflects the impact of penicillin. After the introduction of penicillin, soldiers had little to fear from VD because treatment required only several days in hospital—in contrast to the pre-penicillin era when a VD infection entailed many weeks in hospital undergoing

The Army as an institution most often behaved responsibly by promptly adopting the measures, which, at the time, were thought best for preventing VD infections. Whatever measures were adopted, however, soon proved ineffective in prevention; and so the emphasis shifted. It was a change from moralistic concern with trying to prevent VD among soldiers, as in World War I, to a pragmatic acceptance that VD would occur, that it was an occupational hazard for troops serving overseas and should accordingly be controlled and minimised. The Army came round to the latter viewpoint as a result of its experience in Vietnam. It came to realise that the best it could hope for was to minimise infection rates, not eliminate VD from among its troops.

How many Australian soldiers contracted VD during the twentieth century?

Putting figures for VD infections on particular deployments is often problematic. For some deployments, no statistics are available; for others estimates must be made. Even where figures have been systematically compiled, inconsistencies exist. Further, often the statistics are understated because some soldiers managed to conceal their symptoms; others escaped detection by self-treating; and others were privately treated by civilian doctors. In such cases, the number of VD cases could not be included in the tables compiled by the official medical historians.

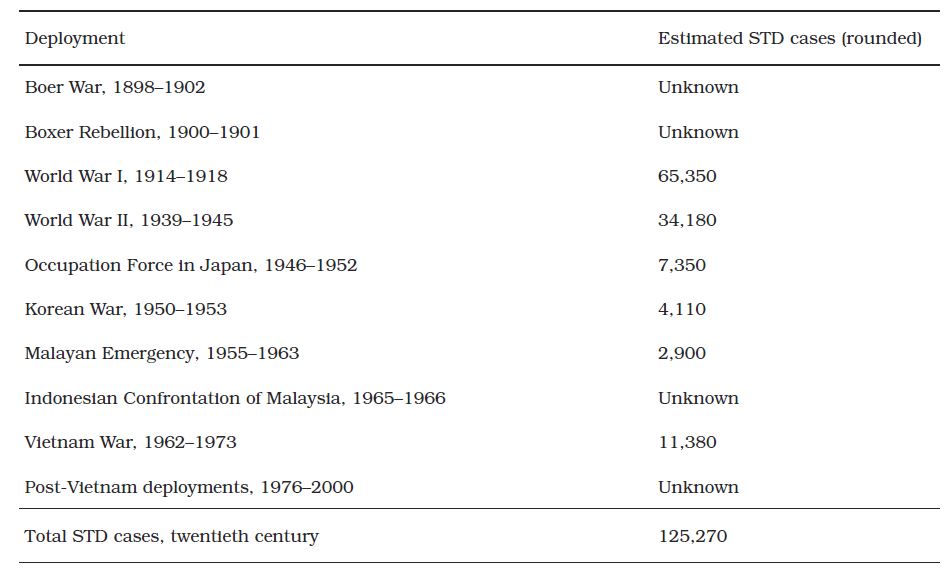

Such provisos notwithstanding, the present author estimates that during the twentieth century Army medical units treated over 125 000 VD cases among Australian soldiers. Table 1 provides a summary.22

The actual total, 125 270, was a nominal figure as it does not include the unknown statistics for four of the 10 sets of deployments. It was a very large sum— the equivalent of six World War I infantry divisions.

What might such a total signify? Does it reflect badly on the soldiers, on the Army that sent them to fight overseas, on the doctors who safeguarded their health, or on the nation of which they were citizens?

The present author proffers no answers to such questions because he has none. Nevertheless, each deployment that contributed to the 125 270 total had its own specificity, which produced its own number of VD cases. The reasons why each deployment produced the VD incidence that it did were complex, relating to circumstances specific to the era and the nations in which the episodes occurred. All that can be said of the total is that VD was a major problem for the Australian Army throughout all its overseas deployments from the Boer War to Vietnam.

Author’s affiliations: Dr Ian Howie-Willis is an independent professional practising historian who lives in Canberra. In July 2018, he finished writing a manuscript with the working title ‘VD: The Australian Army’s experience of sexually transmitted diseases during the twentieth century’. This present article began as a paper presented to the ‘Lessons of War’ section of the Australian Historical Association’s annual conference at the Australian National University on 3 July 2018.

Table 1: Estimated numbers of sexually transmitted disease cases in the Australian Army during the overseas deployments of the twentieth century

Abbreviations

1st AIF – the first Australian Imperial Force: the Australian Army formation established to enable soldiers to enlist for overseas service during World War I

2nd AIF – the second Australian Imperial Force, i.e.Army formation established to enable soldiers to enlist for overseas service during World War II

AIDS – Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

HIV – Human immunodeficiency virus

PAC – Prophylactic Ablution Centre(s): Army units during World Wars I and II, which provided pre-emptive treatment for soldiers who had exposed themselves to risk of VD infection

STD – Sexually transmitted disease(s)

STI – Sexually transmitted infection(s)

UK – United Kingdom

US – United States

VD – Venereal disease(s)

Corresponding author: Ian Howie-Willis, i willis@ozemail.com.au Authors: I Howie-Willis1 Author Affiliations: 1 St John Ambulance Tasmania