Abstract

Background: Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel have been deployed to Afghanistan since 2002. The 2011 death of a US Army soldier from rabies raised the awareness of rabies in ADF personnel deployed in Afghanistan.

Purpose: The study aims to review rabies exposure in ADF personnel supported by the Australian Role 1 health facility in Tarin Kowt, Afghanistan during a 6 month period.

Materials and Methods: The Australian Role 1 rabies vaccination register and associated animal bite reports were reviewed to identify rabies exposures and subsequent management.

Results: 21 ADF members reported a potential rabies exposure during the period.

Eighty five percent were due to a cat bite or scratch with an average delay of 51 days between exposure and reporting, when 32% and 57% respectively were classified as a category II or III exposure. All exposures were managed in accordance with National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) recommendations.

Conclusion: Rabies remains a disease of military significance for ADF personnel operating in Australia’s area of military interest. ADF health staff need to encourage military personnel to minimise contact with local animals and report animal bites or scratches promptly in order to ensure that PEP is administered early.

Keywords: rabies, post-exposure prophylaxis, Afghanistan, Australian Defence Force

Introduction

The rabies virus is a single-stranded RNA virus from the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus which also includes the Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV).1 Humans exposed to saliva or any nerve tissue of an animal infected with rabies may become infected, with the incubation period usually being 3-8 weeks, although the range quoted in separate reports is as short as 1 week and as long as several years after exposure. Rabies is almost invariably fatal, with non-specific symptoms preceding the classical rabies symptoms of a progressive encephalopathy and hypersalivation. Death from cardiac or respiratory arrest usually occurs within 3 weeks of developing symptoms.1

Human exposure can occur via a scratch or bite that has broken the skin, or via direct contact with the mucosal surface of an infected animal. Most human cases of rabies occur after an animal bite(s). Cases following animal scratches, the licking by animals of open wounds or contact with animal saliva when the mucous membranes are intact is very rare.1 Post- exposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves treatment of the acute wound, administration of immunoglobulin and a course of rabies vaccination and approaches 100% effectiveness when conducted with complete compliance.2

Rabies within the Indo-Pacific region

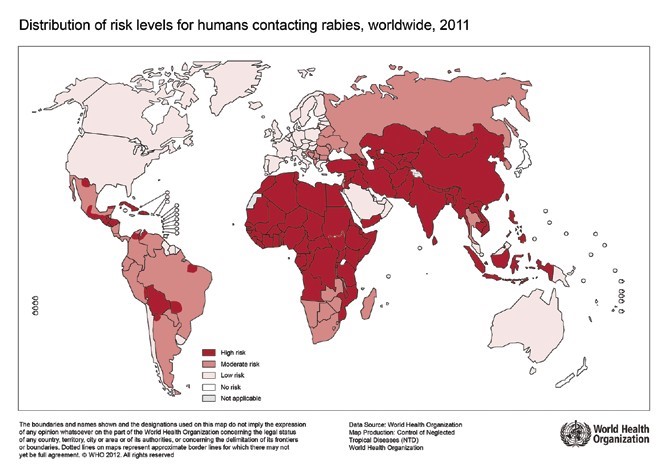

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is required to contribute to contingency and security operations in the Indo-Pacific region, with a priority for o Southeast Asia.3 Rabies remains endemic in most of Asia and human deaths from rabies are estimated to be greater than 30,000 annually.2 Within Asia the only countries considered to be rabies-free are Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, the Maldives, the Malaysian state of Sabah and a number of India’s southern islands. In contrast, most countries in the Pacific Oceania region are considered to be rabies- free and include Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the US state of Hawaii.4 The status can change however, as demonstrated in 2008 when the previously ‘rabies-free’ Indonesian island of Bali reported rabies in local dogs and subsequently in humans.5 Figure 1 illustrates the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2011 world map detailing the risk levels for human contact with rabies, and highlights the large areas within the region that are at medium and high risk of rabies6

|

Box 1. Case report of Death of US soldier from Rabies

Death of US Soldier from Rabies “On August 19, 2011, a male U.S. Army soldier with progressive right arm pain, nausea, vomiting, ataxia, anxiety, and dysphagia was admitted to an emergency department (ED) in New York for suspected rabies. Rabies virus antigens were detected in a nuchal skin biopsy, rabies viral antibodies in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and rabies viral RNA in saliva and CSF specimens by state and CDC rabies laboratories. An Afghanistan canine rabies virus variant was identified. The patient underwent an experimental treatment protocol but died on August 31. The patient described a dog bite while in Afghanistan. However, he had not received effective rabies postexposure prophylaxis (PEP).” Extract from MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012 May 4; 61(17):302-5 |

Whilst the potential rabies reservoir within the region includes a wide range of mammals, dog, monkey and cat bites or scratches were responsible for over 90% of potential rabies exposure in Australian travellers, with approximately 30% resulting from an unprovoked contact.7,8

During contingency or security operations, measures must be taken to monitor and control rabies in endemic areas or to prevent its importation. Lack of such control is likely to compromise the safety of deployed personnel.

The Australian Afghan Experience

The ADF health support plans for deployment to Afghanistan recognised the threat of rabies and pre-deployment health briefs included advice to minimise contact with local animals, but did not emphasise the requirement to report and seek immediate treatment for animal bites or scratches. Currently, preventive medicine personnel, military dog handlers and personnel trained in feral animal capture and euthanasia are required to have rabies vaccination prior to deployment, although prior to 2011 there were no predeployment rabies vaccination requirements. All Australian military working dogs are routinely vaccinated against rabies and have their immunity confirmed by a Rabies Neutralising Antibody Titre Test (RNATT) prior to deployment.9

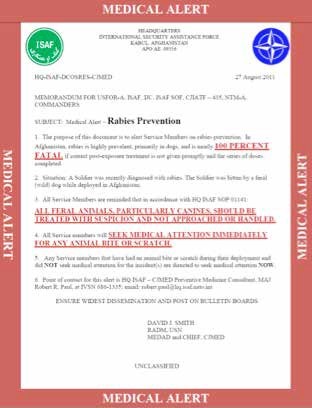

The death of a US Army soldier in 201110 (see box 1) from rabies, following a dog bite whilst deployed in Afghanistan, resulted in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan initiating a formal program of rabies awareness training, tracking, treatment and reporting requirements in September 2011. The ISAF Medical Alert notice, see Figure 2, was issued as part of the program highlighting the need to avoid animal contact and to report any bite or scratch immediately. The Australian post-deployment health screen includes a specific question on whether the member had suffered an animal bite or scratch during the deployment. A number of exposures were identified from positive responses to this question.

Materials and Methods

The Australian Role 1 Tarin Kowt Master Rabies Vaccination register as at 22 January 2012 was used to identify ADF members who had reported a potential rabies exposure in the previous 6 months. The register was an excel spreadsheet compiled in December 2011 and based on monthly animal bite reports between August and November 2011. The ‘NATO-ISAF Report of Animal Attack – Potential Rabies Exposure’ is required to be completed for rabies exposures in non-US personnel deployed to Afghanistan as part of ISAF. These reports were reviewed to establish the date of exposure, the animal species involved, the category of exposure and the date and type of treatment administered. PMKeyS, Defence’s human resource management system, was utilised to access demographic and employment data.

Results

There were 23 reported exposures documented, involving 21 Australian Army members. The remaining 2 exposures were civilian contractors and were excluded from further analysis as ongoing treatment was transferred to another health facility. One exposure was reported after the offending animal had been observed for 10 days and PEP was no longer indicated. In all other cases the full PEP was completed as the offending animal was not observed for the minimum 10 days or tested for the presence of the rabies virus.

A cat bite or scratch was responsible for 18 (85%) exposures, a dog bite for 2 (1%) and not specified in 1 case.12 (57%) exposures were classified as grade III, 8 (32%) graded as II and not specified in 1 case. The reports do not differentiate between provoked and unprovoked exposures. All but 2 cases occurred in a forward operating base within the Uruzgan Province with the remaining 2 cases occurring on the main operating base in Tarin Kowt. Table 1 summarises the nature and treatment of the identified ADF exposures.

There was a significant delay between exposure and the seeking of medical advice, with an average of 51 days and a median of 31 days; Only four cases were treated within 1 week of exposure, all being managed within 24 hours. PEP was administered in accordance with NHMRC guidelines, although three of the four cases received the shorter four dose vaccination course as recommended by the US Center for Disease Control (CDC).

| Rank | |||||

|

Other ranks |

Non- commissioned officers |

Officers |

Total |

||

|

Sex |

Male | 11 | 7 | 1 | 19 |

| Female | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

|

Category of bite or scratch |

I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |

| III | 6 | 6 | 0 | 12 | |

| Not specified | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Time between exposure and presentation (days) | <7 days | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 7-28 days | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 28+ days | 6 | 6 | 1 | 13 | |

|

Source of bite or scratch |

Cat | 9 | 8 | 1 | 18 |

| Dog | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Not specified | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

|

Employment |

Combat | 7 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| Combat Support | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Combat Service Support | 3 | 5 | 0 | 8 | |

Discussion

Despite the pre-deployment and health briefs given at the destination, Australian soldiers of all ranks continued to suffer bites and scratches from local animals. As the vast majority were related to a cat bite or scratch occurring inside a patrol base, most of these exposures could have been avoided had the advice in the health briefs been heeded. More importantly, the delay between exposure and presentation may have had fatal consequences had the injuries resulted in viral transmission. There were medical technicians on all the patrol bases where exposures occurred and there were no cases in which treatment was delayed because of lack of access to medical assistance or PEP.

There were two cases, both preventive medicine technicians(nowrecognisedasahighriskoccupation), whose PEP would have been significantly simplified by pre-exposure vaccination. A change in ADF policy to include rabies pre-exposure vaccination for preventive medicine personnel, military dog handlers and personnel trained in feral animal capture and euthanasia who are on short notice to deploy, would be relatively inexpensive and consistent with NHMRC recommendations for personnel working with terrestrial animals in rabies-enzootic areas.1

The knowledge and understanding of rabies by health staff was generally rudimentary prior to being required to manage a clinical exposure. The deployed medical officers readily identified the requirement to consider PEP and they provided the appropriate PEP despite utilising protocols from a variety of different sources.

Working in a multinational environment can result in variations of the treatment protocols utilised. There were subtle differences between ADF, NHMRC, WHO and CDC policies and guidance at the time. Whilst the ADF policy refers to the NHMRC guidelines, it does not draw the distinction between category II and III exposures, recommending administration of human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) for all exposures in non-immune individuals. The ADF, NHMRC and WHO guidelines current at the time recommended a five dose vaccination course PEP, whereas the CDC had adopted a four dose schedule (which was subsequently adopted by the other agencies). The US military directed their staff to resume the five dose schedule on the basis that antimalarials may compromise the immune system.11 All the major authorities recommended a fifth dose for immunocompromised individuals. The US military directed their staff to resume the five dose schedule on the basis that antimalarials may compromise the immune system.11 Antimalarials are not normally associated immunocompromise at chemoprophylactic dosages. There is evidence that chloroquine specifically interacts with rabies vaccine to decrease its immunogenicity. This has been extended by some sources apply also to mefloquine, despite the available evidence failing to demonstrate any such interraction.12 In any case, the recommendation emphasised that the intramuscular route should be used rather than the intradermal route.4 Antimalarial use should not impact on PEP.

Conclusion

It is likely that rabies exposure will be a feature of future ADF deployments and whilst pre-deployment health briefs should highlight the risk, ADF health staff need to be familiar with PEP and to promote early reporting of animal bites or scratches. ADF policy should be revised to be consistent with NHMRC guidance, pre-exposure vaccination of high risk personnel on short notice to deploy should become standard practice and efforts to specifically address interactions (or lack there of) with antimalarial medications should be made.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Australian Defence Force.

Ethics Statement

The information presented in this paper was collected and analysed as part of routine deployed public health surveillance and, in accordance with the Australian Defence Health Manual Volume 23, does not constitute human research and therefore does not require approval by the Australian Defence Human Research Ethics Committee (ADHREC).