Introduction

The importance of dentists to be able to manage a medical emergency in dental practice has been an established concept for many years, with medical emergency training being incorporated into dental undergraduate training programs as far as back as 19811. However, for far longer than this, dentists have held a professional role in the staffing of military field hospitals, providing emergency care to injured and ill members of the armed forces. Despite awareness of the importance of such skills, Australian studies have shown dentists often lack appropriate proficiencies and equipment for the effective and efficient management of medical crises that may arise as a part of routine dentistry2. The only identified literature review on medical emergencies within dentistry recently found the majority of both students and graduate dentists were unable to correctly perform life support procedures3. This is a finding of concern when recent studies on the prevalence of medical emergencies in dentistry suggest that the incidence may be increasing, due to a myriad of factors3-5. The populations of developed countries are generally getting older and consequently suffer from more acute and chronic conditions6,7; notably, it has been argued that patients with multiple chronic diseases are more likely to suffer from a medical emergency8. Simultaneously, a greater number of practitioners are utilising drugs such as sedatives compared to years past9. These findings coincide with observations that dentists are being taught less clinical medical science than they have historically5, and are further being seen as service providers to a consumerist public, rather than their trained role as health professionals10. Although all schools of dentistry in Australia require their students to hold first aid and basic life support (BLS) certification, the requirements for practicing dentists to undergo ongoing training or medical emergency certification varies across countries and governing bodies11-13. Australian dentists are not specifically required to undergo ongoing training in the management of medical emergencies, despite it being strongly recommended by the Australian Dental Association14. Further, the public’s expectation of dentists’ competence in medical emergency management is likely much higher than what dentists may hold of themselves15, and reports on unpublished studies corroborate this suggestion13. In the current military framework, Australian Defence Force (ADF) Dental Officers (DO) are often involved in the early triaging and stabilisation of injured members who have been evacuated to a role two facility but are not yet in receipt of advanced medical care. This too mandates a high level of knowledge and proficiency in emergency medical management. Given the special semi-autonomous status afforded to the self-regulation of dentistry there is a professional responsibility to meet or exceed public expectations, or such deficiencies may be legislatively mandated. To date, no published studies could be found examining the public’s opinion of dentists’ ability to manage a medical emergency in a dental setting, nor whether a patient’s own medical status impacts on whether they visit a dentist because of concerns about a medical emergency. Based on this, the aim of this research is to quantify the public’s attitudes towards dentists’ proficiency in a medical crisis.

Methods

This paper reports the results of a survey aimed at determining dental patients’ confidence, considerations and expectations of a dentist’s ability to manage a medical emergency in a dental setting. The survey was undertaken at a dental clinic attached to a dental school in Queensland, Australia, during the period April 2018–August 2018. The 23-item questionnaire was developed after undertaking a scoping review of the literature (DOI: 10.1111/adj.12649), exploratory focus groups of dental clinic patients and a subsequent thematic analysis. Validity of survey items was assessed by inviting five subject matter experts involved in the writing of the latest version of the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines Oral and Dental Volume 2, as well as a specialist emergency physician to judge the face and content validity of the questions. Reliability of survey items was determined via a test–retest involving 12 members of the public from the selected sampling site, with surveys carried out two weeks apart. Reliability testing was undertaken using Kappa, with the lowest Kappa for any questionnaire item of 0.9, indicating that the questionnaire items were of excellent reliability. Pilot testing was carried out with five members of the public also from the selected sampling site. A sample size of 385 was deemed necessary to obtain at least ±5% accuracy for any survey item with 95% confidence. A survey was considered complete if >95% of the survey was answered correctly.

Ethics

Ethics approval to conduct the study was granted by the university’s human research ethics committee (James Cook University H7275).

Participants, Data Collection

The site of sampling was the clinic associated with a university dentistry course. This clinic provides free treatment for low-income and concessionary patients, as well as reduced-fee treatment for private patients who do not qualify for public health concessions. Given the availability of free health care for these patients in Australia, medical conditions are typically diagnosed and well controlled. Adult individuals attending the clinic were purposively sampled for this study. Exclusion criteria included being under the age of 18 years, an inability to speak English and any form of training as a healthcare professional. Receptionists provided all patients checking in for their appointment with a copy of the survey, as well as an information sheet. If a patient chose not to complete the survey, it was still submitted into a collection box for assessment of response rate. Following data collection, raw data was transcribed into Microsoft Excel, and subsequently imported into IBM SPSS® for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was primarily descriptive, with counts and percentages presented for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Significance of associations between questionnaire items was assessed using chi-square tests.

Results

Out of the 513 surveys distributed, 385 surveys were completed, resulting in a response rate of 75.0%. The mean (SD) age of those completing the survey was 58.3 (16.1) years, with a gender distribution of 50.1% male and 49.9% female. Table 1 highlights that a clear majority of the public believe dentists to be highly capable at responding to medical emergencies, that it is important for them to be able to do so, and that they would receive regular training to achieve this.

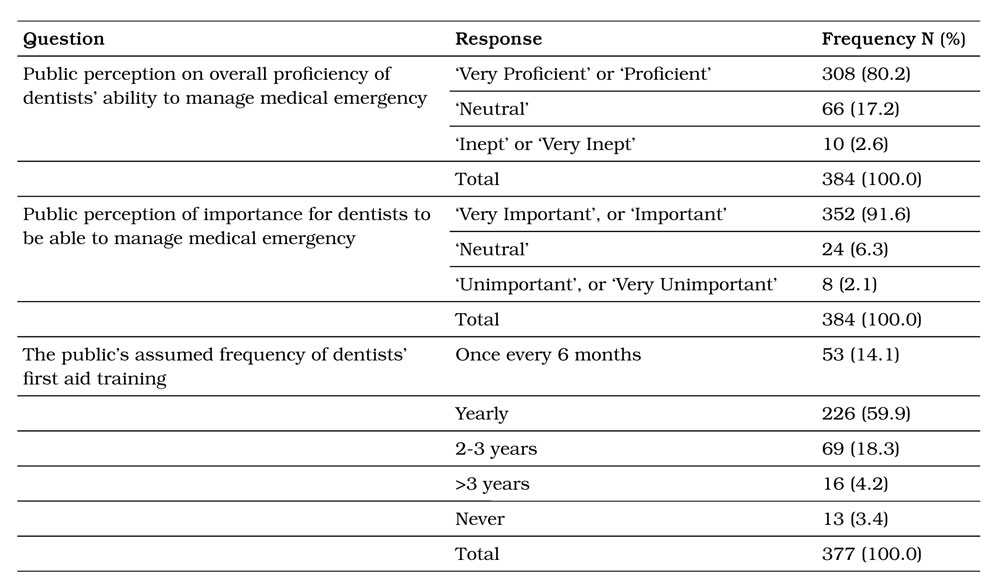

Table 1. Participants’ perception of proficiency and importance of medical emergency management, and assumed frequency of training.

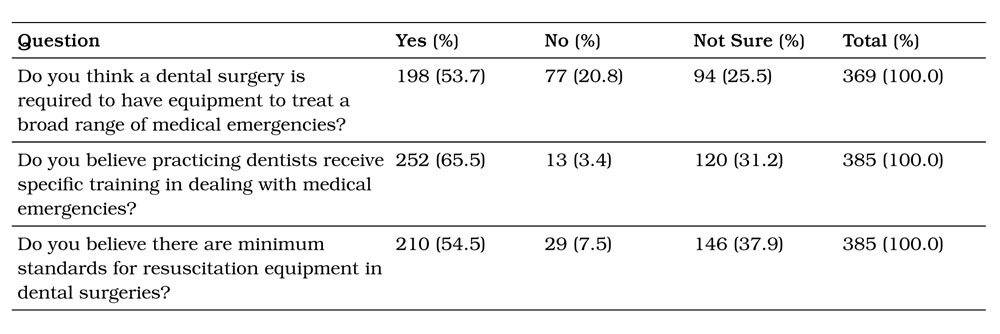

Table 2. Participants’ perception of mandatory requirements related to medical emergency management.

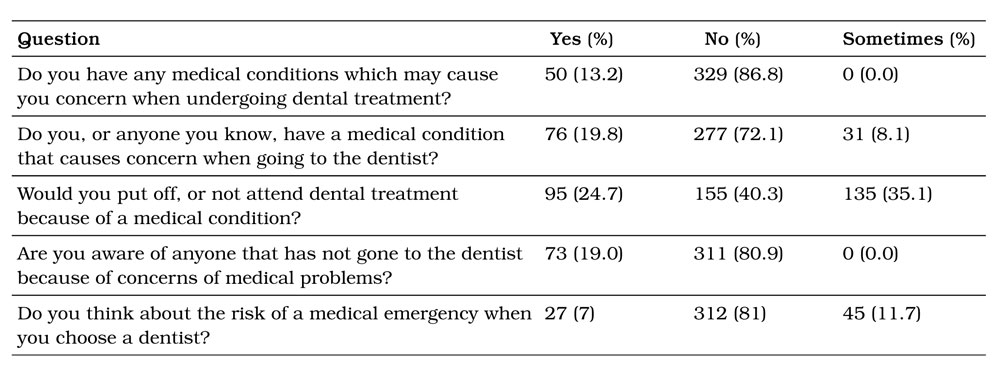

Table 3. Participants’ perceptions of medical risk related to dental treatment.

In response to questions on both the perception of proficiency and importance of medical emergency management, and assumed frequency of training, the results found that 80.2% of the public believed that dentists were proficient or very proficient in dealing with medical emergencies. Further, 91.6% believed that it was important or very important that dentists were proficient in managing medical emergencies. Interestingly, 92.3% of the public believe that a dentist receives first aid training every 3 years or less with 75% of the respondents thought that the training was every 12 months or less.

Table 2 shows that regarding questions relating to the mandatory requirements placed upon dentists and dental surgeries, 53.7% of respondents believed that a dental surgery would be required to hold equipment to treat a wide range of medical emergency. Furthermore, only 7.5% of people believed that no minimum standards would generally apply to resuscitation equipment held within a dental surgery.

Respondents’ perceptions of medical risk while undergoing dental treatment are shown in Table 3. Notably, 13.2% of patients reported a concern stemming from a medical condition when undergoing dental treatment, while nearly 20% reported having a concern themselves or knowing someone with such reservations. Despite these relatively low numbers, more than 50% of respondents said they would further delay or not attend dental treatment entirely if they were to develop such a medical condition. Most surprisingly, 7% of respondents reported actively considering their risk of a medical emergency in their choice of dentist.

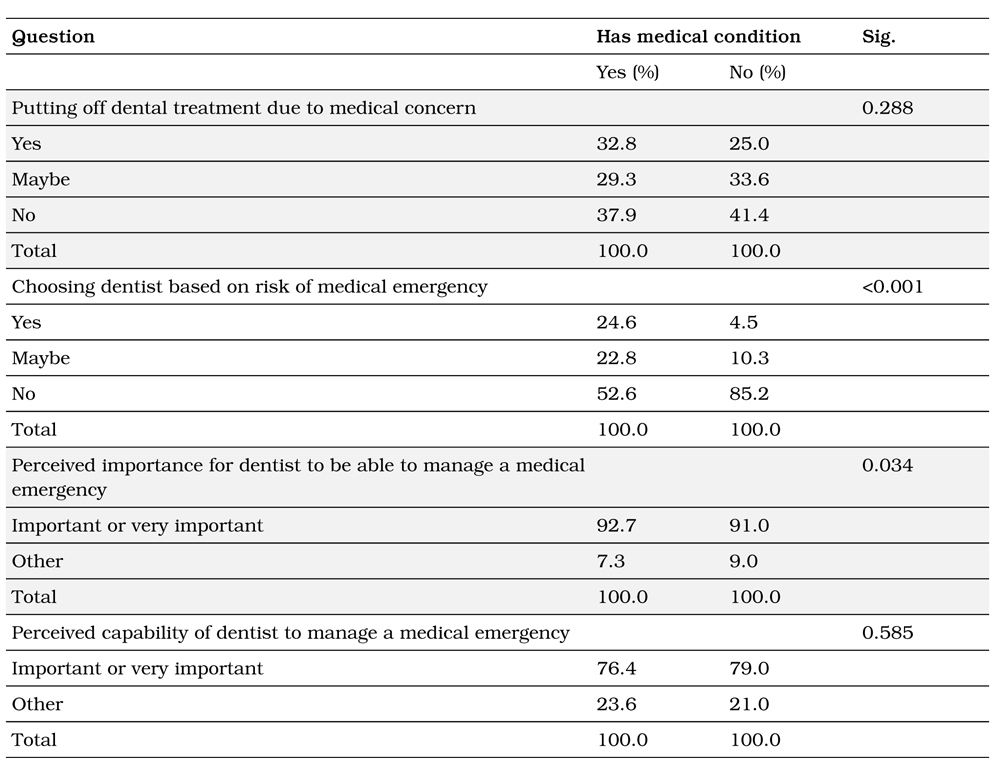

Table 4 demonstrates that respondents with preexisting medical conditions were more likely to find it important for the dentist to be able to successfully manage a medical emergency (p=0.034) and would choose a dentist taking this into account (p<0.001).

Table 4. Associations surrounding a patient’s medical condition.

Discussion

As health professionals, dentists inject drugs and regularly perform invasive surgical procedures. Often these patients are anxious and increasingly older, more medically compromised and more medically complicated. It is therefore not surprising that patients have an expectation that dentists could deal with medical emergencies. Despite this, the current clinical reality in Australia is that there is no mandatory requirement for a dentist to pursue continuing professional development to meet such expectations. Although these results do not represent the current demographics and general clinical reality of the ADF, they highlight existing occurrences in the wider Australian population, which invariably represents a small portion of defence members.

This study found an expectation among the public that dentists undergo medical emergency training every 6–12 months, which is not the case. Existing research suggests that first aid skills significantly degrade within as little as 30 days16, and consideration should be given to the requirement that dentists undergo ongoing medical emergency training to both meet public expectations, and best serve existing guidelines17,18.

Notably, more than 50% of the public would expect dentists and dental surgeries to be required to stock equipment involved in the management of medical emergencies. This sends a clear message of minimum standards that the public would expect a clinical environment to uphold. Furthermore, data from this study shows a widespread belief that dentists would undergo continuing training in medical emergency management. It is well established that although first aid knowledge remains relatively constant following training16, first aid skills degrade rapidly16,19, and multiple medical and health professions further require practitioners to undergo regular skills refreshing20,21. Given existing research reveals dentists and dental students often demonstrate suboptimal medical emergency management3, a requirement to meet public expectations and undergo regular refreshing of medical emergency management skills may be a worthwhile consideration.

The finding that half of all respondents would be willing to forego dental treatment due to a medical condition is interesting and potentially explained by a number of mechanisms. Firstly, no definition was placed on the type of medical condition and could therefore be interpreted in a number of ways; from a common cold through to a complex systemic disease. This willingness may suggest an undervaluation of the benefits of dental health, or a naivety of the established advantages to medical health resultant from the same. Failure to address dental pathology promptly could result in degradation of the condition, continuation of symptoms or the new development of related and potentially more serious outcomes.

Our finding of 20% of respondents reporting either having a personal concern when seeking dental treatment due to a medical condition, or knowing someone with such a concern, is of significance. This is of a much higher value than the authors anticipated, and may speak to a perceived disconnect between dentists’ dental and medical knowledge. No previously published research could be found to compare these results.

The result that 7% of respondents reported giving active consideration to the risk of a medical emergency when seeking dental care was equally unanticipated by the authors. This may be explained by the mean age of participants (58 years), with the tendency for an older population being more aware of their mortality, as evidence has suggested in the past22. Additionally, it is postulated that this concern is more likely to be influenced by other factors shown to affect the public’s choice of medical professional23.

We found a higher than expected number of patients having a medical condition of concern, and this is only likely to increase with an ageing population. It is therefore essential that dental students receive adequate training in handling a medical emergency and that the general public is made aware that they are in safe hands while they are in the dental surgery. ADF DOs are integral members in the provision of emergency medical care and their civilian counterparts hold an arguably greater role when working in private practice. Given it has been seen appropriate for ADF DOs to maintain yearly basic and advanced life support qualifications, the value of such requirements for their civilian counterparts should be closely scrutinised. It is our recommendation that practicing dentists should maintain currency in medical emergency management skills and ensure management plans are in place for the implementation of the same.

This study is the first of its kind to be published examining the public’s perception of dentists’ ability to manage a medical emergency in a dental setting. As of 2018, Australian dental surgeries are only legally required to comply with first aid guidelines set out by Safe Work Australia18, components of which allow varying degrees of subjectivity in the context of a dental surgery. It should therefore be reinforced to practitioners that medical emergency management should revolve around two core concepts if accusations of malpractice or negligence are to be avoided. Primarily, this comprises the immediate and comprehensive stabilisation of a patient’s medical condition via both physical and pharmaceutical processes. Secondly, if appropriate, arrangements for urgent hospital retrieval must be undertaken as soon as feasibly possible to ensure timely escalation of patient care. Given existing guidelines do not explicitly elucidate risks and requirements for dental surgeries, it is the practitioner’s responsibility to ensure that their procedures are of such high quality that no justifiable complaints could arise.

Limitations

There is the potential for selection bias, as participants were invited for inclusion based on their attendance at a student clinic, where the majority of patients qualify for free public health care due to low socioeconomic status. Further, like all surveys of this type, we were reliant on participants’ self reported knowledge and attitudes.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that the public believe dentists to be generally proficient at medical emergency management. These expectations exceed proficiency levels currently being reported, and skill improvement and preparedness in the management of medical emergencies may be required in order to meet public expectations.

Corresponding Author: Flight Lieutenant Matthew

Vaughan BDS, mattvaughan@gmail.com

Authors: M Vaughan1,2, G Mahoney2, A Sholapurkar3, A Esterman4

Author Affiliations:

1 Joint Health Command

2 Royal Australian Air Force

3 College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook

University

4 Tropical Health and Medicine, James Cook

University, Australia