Abstract

Background: The widely-used Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) has practical and theoretical limitations. The Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C) was developed to overcome these shortcomings but requires more psychometric analysis to determine its utility.

Purpose: To compare DAS and IDAF-4C validity and reliability among New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) personnel.

Material and methods: A survey of NZDF recruits and officer cadets collected data on dental anxiety using the IDAF-4C, the DAS and a global dental anxiety item.

Results: Some 134 individuals completed the questionnaire. Confirmatory factor analysis for the IDAF-4C showed that a single factor explained 72.4% of the variance. The IDAF-4C showed high internal consistency reliability (α = 0.94). Confirmatory factor analysis for the DAS showed that a single factor explained 69.5% of the variance. The DAS showed high internal consistency reliability (α = 0.85). While the IDAF-4C showed a consistent gradient in mean scale scores across response categories of the global dental anxiety question, the gradient for the DAS was less consistent. The IDAF-4C and DAS showed considerable concordance (r = 0.71).

Conclusion: The IDAF-4C demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, validity and reliability, and it is a valid and useful instrument for measuring dental anxiety and fear in Defence Force personnel.

Keywords: Dental anxiety; measurement scales; adults

Introduction

Dental anxiety and fear are problems that are not fully understood due to their complex nature and aetiology. High dental anxiety and fear are associated with adverse psychosocial consequences such as lower self-esteem and morale.1 It has been almost universally observed that dental anxiety and fear are more common among women than men.2-5 Dental anxiety also negatively affects oral health and general wellbeing.6-8 It is a major contributor to irregular dental attendance and prolonged avoidance of dental treatment.9 Such avoidance is likely to result in poorer oral health, with people who are dentally fearful having (on average) more decayed surfaces, fewer restored teeth and more missing teeth than their non-dentally fearful counterparts.5,10 This occurs through a vicious cycle of dental fear, whereby individuals with high dental fear are more likely to delay treatment. Such symptomatic visiting results in more invasive dental procedures that feed back and maintain or exacerbate the existing dental fear.11 Dental fear is also associated with a higher prevalence of toothache, being uncomfortable with the appearance of the mouth, teeth or dentures, and avoiding particular foods because of dental problems, along with lower life satisfaction and trouble sleeping due to dental problems.11

Dental anxiety must be measured through self-report, but existing dental anxiety scales have their flaws, many of which arise from their inability to embrace contemporary understanding of dental anxiety aetiology.12 Using different scales results in different prevalence estimates. The prevalence of dental anxiety has been reported to range from as low as 7.3% to as high as 28.4%, and an Australian study found a low degree of concordance among estimates using three existing measures.12 A key issue when using a scale to measure dental anxiety is that the scales measure different constructs differently.12-13 To date, the most extensively used scale has been the four-item Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS), on which an individual’s score can range from 4 (least anxious) to 20 (most anxious).14 A score of 13 or above classifies a person as ‘dentally anxious’. The DAS has been criticised for the lack of a conceptual basis behind its development, the threshold score of 13 being wholly arbitrary, and its inability to adequately distinguish differing levels of dental anxiety (instead, it is more likely to identify high and low, but not moderate anxiety). Another flaw is that the items lack consistency, and the response options are neither mutually exclusive nor reflect dental anxiety using a scale in the ordinal manner required in such instruments.15 Somewhat surprisingly for such a scale, the DAS does not refer to injections for local anaesthetic, which is known to be associated with dental fear.16

The Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF) was developed to overcome such limitations.17 It is based on theory and has three modules, which (respectively) measure dental anxiety and fear, dental phobia and feared dental stimuli. Armfield developed this approach to allow researchers and clinicians to use the module of interest while considering the different origins of dental fear and/or anxiety. The abbreviation IDAF-4C+ represents the modules comprising the index, which measures an individual’s cognitive, emotional, behavioural and physiological components, while the ‘+’ represents the added modules. The IDAF-4C is the core module determining the respondent’s overall level of dental fear. This instrument comprises eight items, with two assessing each of those four components of anxiety and fear. Responses are collected using a 5-point Likert scale reflecting how strongly participants agree or disagree with an item. The responses are summed and then standardised by dividing the total score by the number of items, and a score of 3 or more defines someone as dentally anxious.17

Because there is no ‘gold standard’ dental anxiety scale, finding a reference point against which the validity of such a scale can be tested is challenging. Accordingly, the psychometric properties of this scale must be examined across a range of populations instead of basing it on a single set of observations.18 The psychometric evaluation of the IDAF-4C has been undertaken in a smaller number of studies, mainly limited to Australia17 and New Zealand.19 The latter compared the psychometric properties of the IDAF-4C and the DAS. The IDAF-4C showed good evidence of validity in terms of the underlying factor structure and associations with dental service use. There was a moderate correlation (Pearson’s r of 0.78) between the IDAF-4C and the DAS, and the IDAF-4C explained greater variation in dental visiting patterns than the DAS did. Approximately half of those classified as dentally anxious by the DAS were also categorised as dentally fearful by the IDAF-4C.19

Typically, New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) recruits are adults between 17 and 25 years old.20 From a dental anxiety and fear viewpoint, this is an important life stage because of the higher risk of onset and/or consolidation of dental anxiety, along with the risk of a marked decrease in dental visits, particularly if individuals do not overcome their dental anxiety.10,21 They are then likely to carry the burden of their poorer oral health onward through life.

The IDAF-4C was developed to overcome the shortcomings of the DAS but requires more psychometric analysis to determine its utility, especially given the low number of studies that have compared the two measures. Accordingly, this study aimed to compare the psychometric properties of the well-used but flawed DAS and the relatively new and conceptually sound IDAF-4C in a sample of NZDF personnel.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Otago Ethics Committee (Category B; D18/200) for a cross-sectional study of New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) recruits and officer cadets. The original sample of participants consisted of 874 recruits and officer cadets (701 males, 80.2%; 173 females, 19.8%) who had entered the NZDF in the 13 months between 1 July 2018 and 31 July 2019. The baseline sample had the following characteristics: one in five were Māori; the age range was 17 to 59 years, with only nine older than 35 years (most were aged between 17 and 24 years); the highest level of education attained by 45% of the sample was primary/secondary school; and one in eight were of high SES.

The current study recontacted 134 individuals at their annual dental check-ups between April and August 2021. After written informed consent was provided, they completed a socio-dental questionnaire prior to their dental examination (note that the questionnaire given to the participants at the time of their initial dental examination did not include any dental anxiety measures. The baseline assessment was largely clinically focused, and we had always intended to bolster the self-report component at the second assessment).

Dental anxiety and fear were measured using both the IDAF-4C and the DAS.14,17 The IDAF-4C comprised eight items, with two items assessing each of the four different components of anxiety and fear. The response option was a 5-point Likert scale where respondents placed themselves according to how strongly they agreed or disagreed with an item. A mean score of 3 or more defined someone as dentally anxious.17 The DAS had four response items for which responses were summed. An individual’s score ranged from 4 (least anxious) to 20 (most anxious). A score of 13 and above classified a person as dentally anxious. The global validation item for the two dental anxiety scales was ‘Overall, how anxious are you about visiting the dentist?’, with respondents asked to place themselves on a 4-point Likert scale, with response options ‘Not at all’, ‘Somewhat anxious’, ‘Quite anxious’ and ‘Very anxious’. The global item was placed early within the study questionnaire to separate it from the dental anxiety scale items. It was developed to provide an ordinal global measure of dental anxiety against which the concurrent validity of the two multiitem scales could be assessed; such validity would be confirmed if there was a marked and consistent gradient in mean dental anxiety scale scores across the ordinal categories of the global measure.

Data were analysed using version 26 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Confirmatory factor analysis for the DAS and IDAF-4C was undertaken, employing principal axis factoring (with promax rotation) as the extraction method and Kaiser normalisation. The two scales’ internal consistency reliability was compared using Cronbach’s alpha. Dental anxiety scale scores were then computed, and their concurrent validity was assessed by examining the mean DAS and IDAF-4C scores across the ordinal categories of the global self-reported dental anxiety question. The concordance between the two dental anxiety scales was examined using Pearson’s r correlation coefficient and a scatterplot.

Results

Sociodemographic details are not available for the 134 participants in this analysis.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The exploratory factor analysis for the IDAF-4C showed that single factor loadings were acceptably high and were on a single factor; only one of the Eigenvalues was greater than 1, at 5.8. That single factor explained 72.4% of the variance in the IDAF-4C responses. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94. The exploratory factor analysis of the DAS showed that the items loaded on a single item and the loadings were acceptably high, with only one of the Eigenvalues greater than 1, at 2.8. This single factor accounted for 69.5% of the variance in the DAS responses. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85. A summated score of 13 for the DAS and an alternative mean score of 3 for the IDAF-4C was used to define dental anxiety.

Concurrent validity

The two dental anxiety scales showed reasonably consistent and statistically significant gradients in mean scale scores across the response categories of the global question (Table 1).

Table 1. Concurrent validity of the two scales: mean IDAF-4C score and mean DAS score by responses to the global dental anxiety question.

| Global Dental Anxiety Score | N (%) | Mean IDAF-4C (sd) | Mean DAS (sd) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | 86 (64.2) | 1.1 (0.4) | 5.8 (1.7) |

| Somewhat anxious | 40 (29.9) | 1.5 (0.5) | 9.2 (2.3) |

| Quite anxious | 4 (3.0) | 2.4 (1.1) | 11.8 (3.0) |

| Very anxious | 4 (3.0) | 2.9 (0.9) | 11.3 (3.0) |

| All combined | 134 (100.0) | 1.3 (0.6) | 7.2 (2.7) |

Concordance between the scales

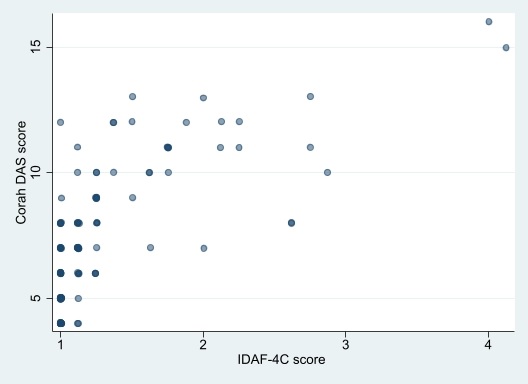

The correlation between the IDAF-4C and the DAS was strong, with r = 0.710. This is illustrated in the scatterplot (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scatterplot of the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C) and the Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) scale scores

The prevalence of dental anxiety, according to the IDAF-4C, was 2.2%, while it was 3.7%, according to the DAS. The kappa statistic (k = 0.486) indicated only moderate concordance between the DAS and IDAF-4C prevalence estimates. Five individuals were classified as dentally anxious by the DAS, but only two were classified as dentally anxious by the IDAF-4C. The IDAF-4C classified three individuals as having dental anxiety, and two of those individuals were classified as dentally anxious by the DAS.

Discussion

This study compared the performance of two important dental anxiety and fear scales in a sample of NZDF recruits. It found that both had sound psychometric properties and acceptable reliability and validity, and they showed reasonable concordance. Despite this apparent equivalence, the IDAF-4C is likely to be a better measure for use in young adults because of its more robust theoretical underpinning, as highlighted by Armfield17 (a close read of the original DAS paper14 shows just how ad hoc that measure’s development was).

Before discussing the findings in detail, the study’s weaknesses and strengths must be considered. The effective participation rate was relatively low, at 15.3%. Several factors conspired to make it so. The study was originally intended as a complete follow-up of the 874 personnel who had entered the NZDF between 1 July 2018 and 31 July 2019 and whose baseline characteristics have already been reported.20 However, not all individuals from the original sample could be contacted again because some would have left the Forces. Another external factor was the national lockdown arising from the COVID-19 pandemic; this delayed data collection until April 2021, which meant the period available for that was shorter than initially anticipated. The recruits had also been dispersed across different NZDF bases around New Zealand, meaning time had to be taken to locate them and then send the questionnaires out to the appropriate bases in time for the dental check-ups. All of these factors resulted in a lower participation rate than initially anticipated. While high response rates in surveys are preferred, low response rates do not necessarily lead to bias as long as there are few (or no) systematic differences between the responders and non-responders.22 We had planned to compare the characteristics of those reassessed and those lost to follow-up. However, an NZDF clerical procedural error meant that respondents’ unique identifiers were not entered into the database before the paper questionnaires were destroyed. Accordingly, we cannot determine the extent to which the relatively low response rate may have affected the findings, and neither are we able to report on the sociodemographic characteristics of our follow-up sample. Notwithstanding these concerns, we did end up with sufficient N to test the number of items being investigated (with a participant-to-item ratio of 11 for the DAS and IDAF-4C combined). A post hoc power analysis showed a required N of 16 to show the difference in mean DAS scale score between those responding ‘Not at all’ and those responding ‘Very anxious’ to the global dental anxiety question (Table 1) with an alpha value of 0.05 and 95% power to detect a difference (and an effect size of 1.8, calculated by dividing the difference in scores by the SD of the score for those responding ‘Very anxious’ to the global dental anxiety question).

The NZDF requires individuals to undergo a yearly dental check-up. The IDAF-4C has two items that do not apply to the current study’s sample because the personnel have no choice about when or whether they have their yearly dental check-up. Those two items are ‘I generally avoid going to the dentist because I find the experience unpleasant or distressing’ and ‘I delay making appointments to go to the dentist’. Since the participants had entered the NZDF in 2018–19, they would have had at least 3 compulsory dental check-ups. Dental anxiety is associated with symptomatic attendance, leading to more invasive procedures, which themselves serve to exacerbate dental anxiety further.11 These NZDF recruits and officer cadets may have undergone a degree of operant conditioning through their experience of regular check-ups and non-symptomatic attendance. This may have led to lower levels of dental anxiety and correspondingly lower IDAF-4C scores. This might have affected the concordance between the DAS and IDAF-4C (although that was relatively high) and the validity of the IDAF-4C in this sample.

The primary focus of this project was to assess the validity and reliability of the IDAF-4C scale and to compare it with the DAS. The IDAF-4C is the core module of the IDAF-4C+, a suite of scales used to measure dental anxiety and fear. There is currently no ‘gold standard’ global dental anxiety scale against which to test the IDAF-4C, so we chose to use the DAS, the most widely used and accepted scale.14 Validity should also be examined using several approaches.18 In the IDAF-4C scale’s development, Armfield employed several methods to assess its validity, including factor analysis, examining associations with other dental anxiety scales, and determining its ability to predict subsequent dental visiting patterns.17 We confirmed its factor structure and internal consistency reliability, examined its concurrent validity against a global dental anxiety question, and then directly compared it with the DAS. There was a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), and the confirmatory factor analysis showed that a single factor accounted for 72.4% of the variance in IDAF-4C responses. This was higher than in the only other New Zealand study.19 The IDAF-4C displayed good validity against the global dental anxiety question, with an ascending gradient of mean scale scores across its ordinal categories, consistent with the earlier study.19 Finally, the IDAF-4C and DAS showed high concordance, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The low overall prevalence of dental anxiety in the sample meant that no firm conclusions could be drawn from this study about the respective utility of the two measures in determining the proportion of the population who suffer from dental anxiety. This was similar to the earlier NZ findings.19

This study has contributed to the validation of the IDAF-4C. To continue advancing knowledge in this field, research that investigates the occurrence and associations of dental anxiety with sociodemographic characteristics, oral care and oral status would be beneficial. The ability of the IDAF-4C to predict subsequent dental visits, avoidance of the dentist due to fear and specific stimuli—as well as its test-retest reliability—should be examined in other samples, particularly in populations with more severe dental anxiety and fear. The finding that the IDAF-4C demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, validity and reliability adds to the increasing evidence to support the assertion that the IDAF-4C is a valid and valuable instrument for measuring dental anxiety and fear.

Corresponding Author: William Murray Thomson, murray.thomson@otago.ac.nz

Authors: M van Kuijk2, K E Naysmith3, L A Foster Page4, D Tong5, W M Thomson1

Author Affiliations:

1 University of Otago Sir John Walsh Research Institute

2 University of Otago School of Dentistry

3 New Zealand Defence Force Health Directorate Wellington

4 Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland OR, USA

5 University of Otago – Oral Diagnostic and Surgical Sciences