The Spanish–American War

In 2014, the US Army deployed 2500 soldiers into Liberia, West Africa, as part of a global response to an Ebola outbreak. Despite the fear of viral spread from civilians, no cases of Ebola occurred in US or UK military members, and very few febrile soldiers were seen with other complaints.1 The ADF declined the invitation of its USA and UK allies to participate in the 2014 Ebola mission for many reasons, primarily geographical. However, fear of lethal infection by a haemorrhagic fever virus was undoubtedly a contributing factor. Advanced diagnostic means were field deployed to assist in the public health efforts to break the chain of infection, particularly within the deficient health care system.2 Many more civilians likely died of malaria than Ebola as the health system failed to deliver even simple medications.3 An analogous, but certainly not identical, set of events occurred during the Spanish–American War at the end of the 19th century, where fear of yellow fever, another highly lethal haemorrhagic fever, distracted from the leading cause of mortality, which was typhoid fever due to a breakdown in field sanitation in recruit camps. Laboratory tests proved crucial to convincing medical officers that what they were clinically diagnosing as malaria was, in reality, caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Eventually, disease control was instituted, but not before the end of the war and several thousand preventable soldier deaths. Therefore, the fear of yellow fever distracted from the preventable typhoid fever deaths, misdiagnosed as malaria due to inadequate laboratory methods.

The small US Army (n=25 000) grew by a factor of 10 after war was declared against Spain in 1898, and masses of raw volunteers moved into military training encampments that were rapidly thrown together. Microbiology was a cutting-edge science driven by the Pasteurian revolution and the personal interest of bacteriologist and Surgeon-General Sternberg. Unfortunately, clinical medicine had not caught up with the new findings that malaria was caused by blood parasites spread by mosquitoes and typhoid fever was an enteric infection caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Thousands of contract surgeons hired to expand the tiny US Army Medical Corps (n=332) had little knowledge of field hygiene. Few officers of any rank had personal experience with large bodies of soldiers since the US Civil War >40 years previous to the events that saw an amphibious expeditionary force assembled and launched at Cuba in a matter of few weeks. Thousands of men were infected by typhoid fever in camps with only rudimentary sanitation facilities that were usually ignored by ill-disciplined volunteers anxious to get to the fighting before the war was over. In the absence of any laboratory means, the epidemic was widely proclaimed as being malarial. The US Army Medical School (established in 1893 by Sternberg to train military medical officers and later became Walter Reed Army Institute of Research) graduates were brought from Washington to show there were no blood parasites. The Surgeon-General eventually concluded, ‘Without any doubt, many of the deaths ascribed to “malarial fevers” were in fact due to typhoid infection’.4

What the soldiers and medical officers were afraid of was not typhoid but an epidemic of yellow fever. This infamously lethal haemorrhagic fever spread from the tropical Caribbean into the Southern USA in the summer before abating during cooler weather.5 Yellow fever had destroyed a previous French effort to form an American Empire and seemed likely to disrupt the United States’ attempt to displace the old colonial power Spain. Yellow fever did start to kill US soldiers in Cuba after the brief combat phase was over, causing a politically driven campaign to get the now redundant soldiers back ‘home’ before they were decimated by disease in Cuba. By a remarkable coincidence, the same military medical commission formed to stop the typhoid epidemics in USA recruit camps was now employed in Cuba to study yellow fever. The tremendous scientific success of the group led by MAJ Walter Reed in defining yellow fever epidemiology should not overshadow their previous unglamorous work on field sanitation in filthy recruit camps.6

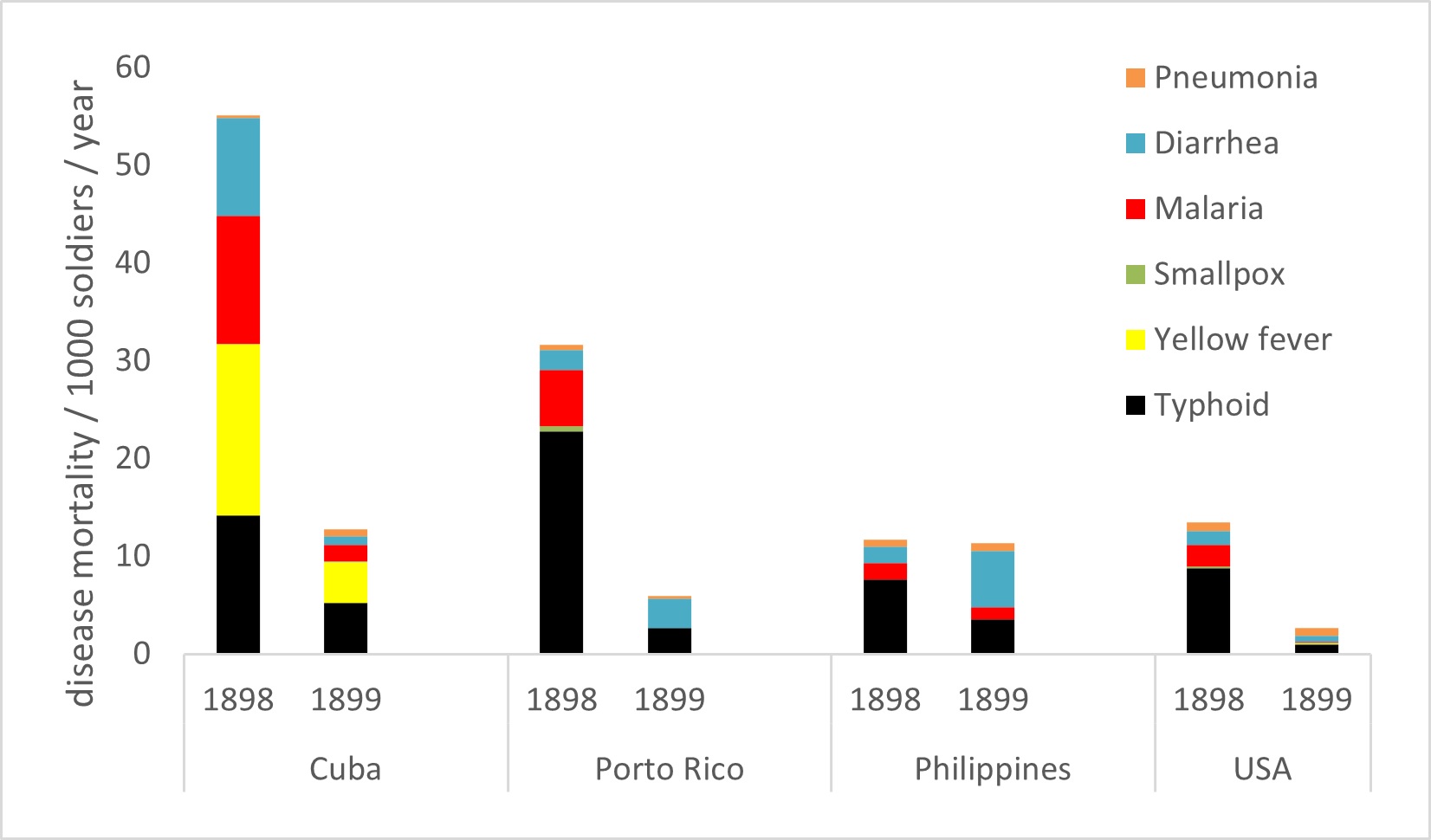

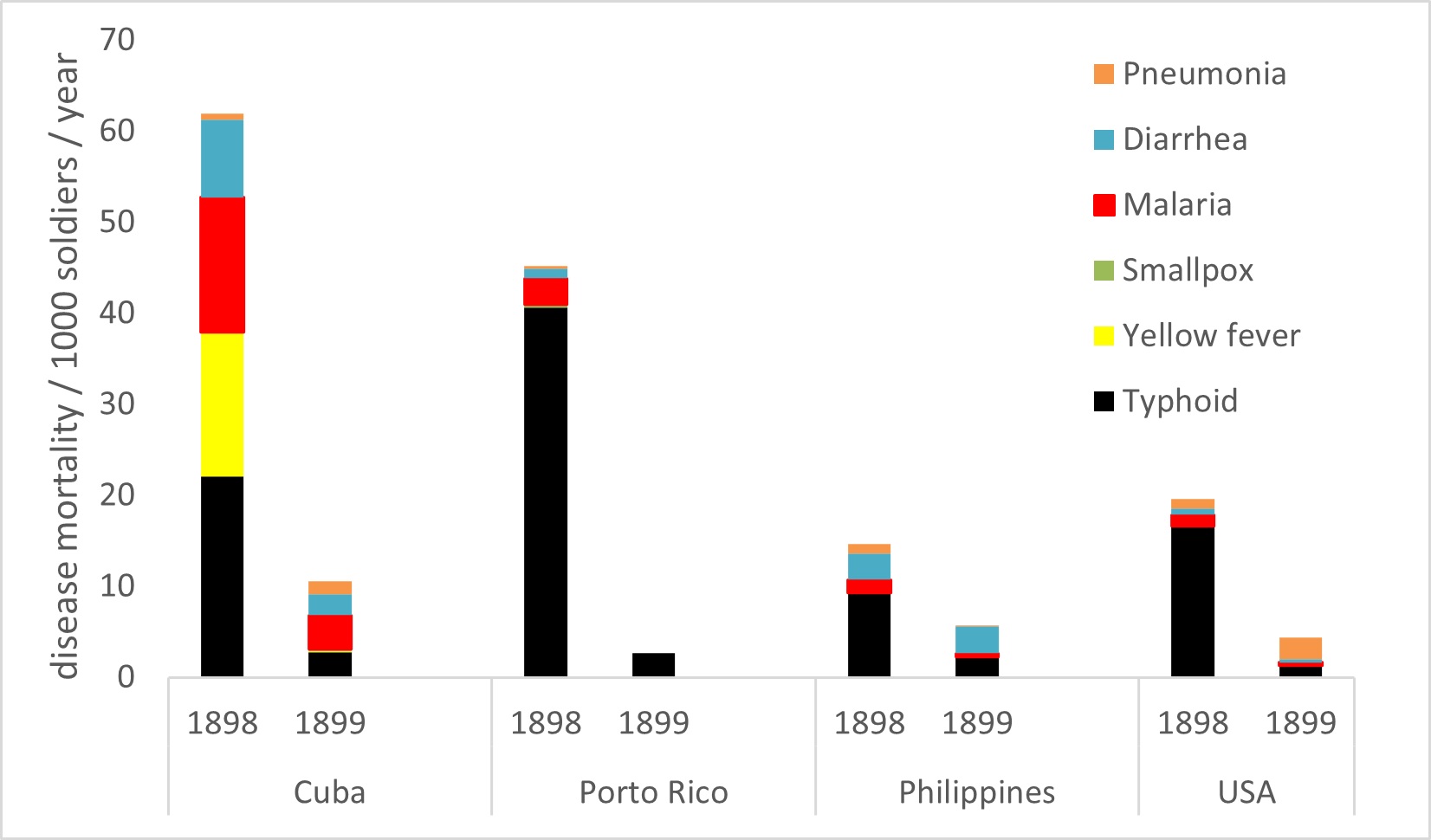

That typhoid was the leading killer of soldiers can be seen in Figure 1, which reconstructs the mortality rates from the Surgeon-General’s reports.7 The regular soldiers (1A) were less affected by typhoid and more subject to yellow fever than the volunteers (1B) because they were deployed first to Cuba. They were likely more disciplined and stayed out of the septic recruit camps. All disease mortality fell rapidly in the next year due to the institution of important hygienic reforms and volunteer demobilisation. A comparison of Cuba (where there was yellow fever transmission) to the Philippines (where yellow fever does not exist) is useful to see the high background mortality, which was not dissimilar to the USA, where 1% disease mortality was expected annually at the beginning of the 20th century.8

Figure 1: Infectious disease mortality in US Army soldiers during the Spanish–American War, both in USA and on three islands involved in the expeditionary forces (Cuba, Porto Rico, Philippines) from both 1898 (first column) and 1899 (second column) based on Annual Reports of the Surgeon-General.7 A. Regular soldiers (n=25 000) and B. Volunteer soldiers (n=200 000) raised in 1898 for the conflict with Spain.

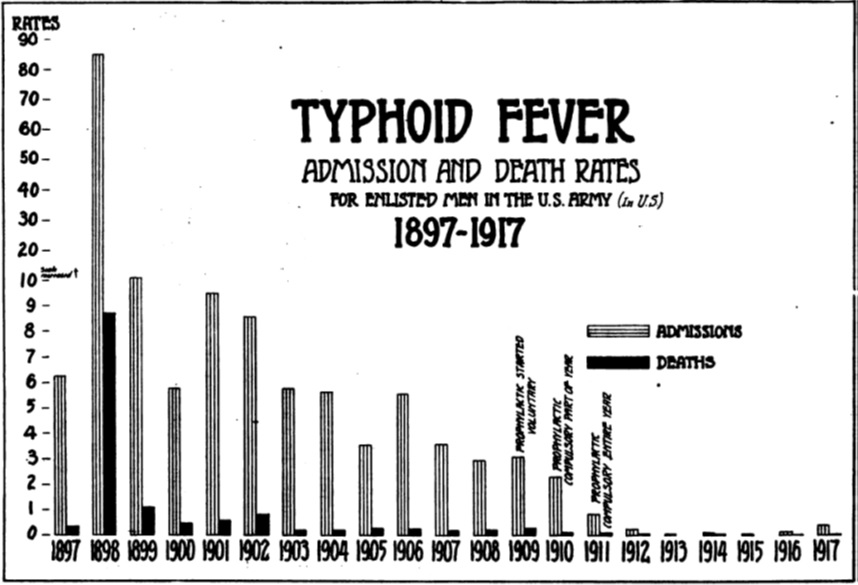

The real solution to typhoid fever in the military still lay in the future with an effective British Army vaccine, which was only then being devised by work during the South African (Boer) War under Sir Almoth Wright.9 Although crude by modern standards, a phenol-killed bacterial culture of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi contained enough endotoxin to produce sore arms and some protective immunity. MAJ Frederick Russell was sent to study the British Army’s vaccine, where he introduced a US Army version, which had become compulsory by 1911. The results in disease and mortality reduction are clearly shown in the figure reproduced from the 1918 Surgeon-General’s report shown in Figure 2.8 The live, attenuated yellow fever vaccine, which is still in use today, would have to wait another generation for Max Theiler of the Rockefeller Institute to figure out how to grow viruses in eggs. Although the vaccine was used widely during World War II, primarily due to concern that the Imperial Japanese Army would use yellow fever as a biological weapon, its protective effect was overshadowed by the unintended consequences that produced an enormous, iatrogenic epidemic of hepatitis B from a contaminated vaccine component.10

Figure 2: Typhoid fever morbidity and mortality rates in US Army enlisted men in the USA from 1897–1917 as shown in a figure taken from 1918 Annual Report of the Surgeon-General. Typhoid fever fell precipitously once field sanitation had been established in camps (1899) and immunisation introduced (1910).8

The US military conducted successful deployments during both the 2014 Ebola epidemic and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic despite neither vaccine being available when the mission started. The ADF must consider the theoretical risk of Nipah/Hendra virus infections during regional deployments, knowing that fruit bat avoidance measures are likely to succeed even without a registered vaccine. The analogous but contrasting experiences during the Spanish–American War with both typhoid and yellow fever are sobering and instructive. Fear runs ahead of science and often does not correlate with what is causing casualties. Common infectious diseases are more important to military operations than those that are more newsworthy because of their higher lethality. It remains challenging to introduce new immunisations after an epidemic event has begun; great uncertainty applies to how long it will take to develop a new vaccine, and compulsory immunisation is required to deliver an effect to the entire force. The Spanish–American War is likely the most disrupted USA war by infectious disease. Our duty remains to see that future military operations do not have to re-learn the same difficult historical lessons concerning the rapid expansion of military forces into a tropical area of operations.

Funding: No specific funding was given for this work.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Defence Force or the US Department of Defense.

Conflicts of interest: The author does not claim any conflicts of interest.

Corresponding Author: G D Shanks, Dennis.Shanks@defence.gov.au

Authors: G D Shanks1,2

Author Affiliations:

1 ADF Malaria and Infectious Disease Institute

2 University of Queensland – School of Public Health