Incorporating Reflective Practice as an Assessment Tool in the Training of New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) Medics

Wendy Maddocks

Abstract

The New Zealand Defence Health Directorate changed its strategic vision in 2016 in the way the New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) provides medic training. This change provided an opportunity to analyse the value of using reflective practice as a summative assessment during the first primary health care (PHC) on job experience (OJE).Approval was gained from the Commanding Officer (CO) of the Defence Training Institute (DTI) and the Chief Instructor (CI) of the Defence Health School (DHS [NZ]) for the author to gain access to the learners and conduct voluntary interviews. The first cohort of Military Medical Technicians (MMTs) (n=14) were interviewed twice while the MMT learners were on OJE at NZDF Health Centres. A retrospective analysis was conducted on the responses received, identifying the benefits from using the selected model which required them to reflect on clinically based encounters and link their experience with the literature. Key benefits included evidence of increased confidence, skill utilisation and self-awareness.

Background

NZDF tri-service MMTs and Medics provide routine PHC to military personnel as part of a multidisciplinary team. In addition, they are trained to respond to requests from the New Zealand Government for tactical or Humanitarian and Disaster Relief. Training is provided by the DHS (NZ) who receives clinical leadership from the Defence Health Directorate. In February 2017, the first cohort (n=14) commenced the new syllabus of learning which had been designed to meet job specific requirements suited to all three NZDF services (Navy, Army and Airforce). Instruction over the 30 months includes residential theory and simulated practical, and extensive blocks of learning in various NZDF PHC and operational settings.

The focus of OJE is to apply the skills and knowledge already acquired into real life encounters, in addition to ‘just in time’ (JIT) learning where a learner is coached by senior clinical staff if they have not learnt the skills. Given the unpredictable nature of military health care this, and being able to respond appropriately in accordance with NZDF policy, is an important part of their learning. This article explores and analyses the use of reflective practice by MMT learners during their first OJE in a NZDF PHC setting.

Reflective Practice Literature Review

Reflective practice is a learning tool used in various health and education learning contexts1 with increased uptake by pre-hospital health providers (e.g. paramedics) 2.This process helps formalise subconscious thoughts and actions to a more deliberate and systematic process to help inform future practice.3 Proponents argue it is of most value when it is implemented early in training when skills are not intuitive, and continue through the entire training continuum.4 The key premise of reflective practice, reflective journaling or critical reflections is that the learner gains insight into their clinical decision making process, away from the environment in which the learning has occurred. The reflection is then presented against a backdrop of a critical analysis of literature relating to the incident or experience.5, 6

While all reflective models offer an element of looking deeper into a situation, not all require looking beyond the situation and researching literature to support the reflection, thus limiting the academic value.7 The DHS (NZ) encourages medic learners to engage with extant and emerging literature early within their learning and to develop a ‘best practice’ mind-set providing evidenced based care for future patient encounters.8 The key point is to make the linkage between theory and the clinical experience.1 This may start with an uncomfortable feeling or thought which the learner then questions.6

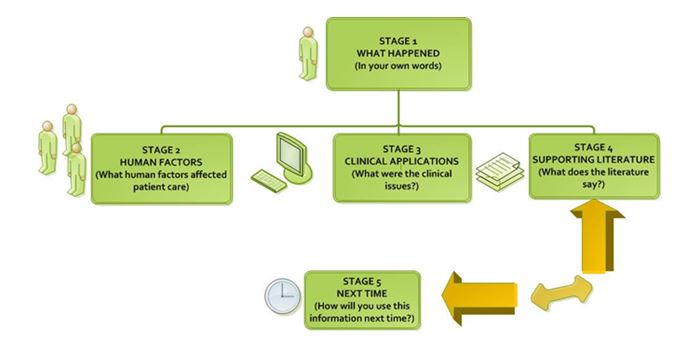

Figure 1: Reflective Practice Model as used by NZDF (Willis, 2010)8

A model developed for paramedic use by Willis8 was selected as it is based on pre-hospital contextual elements which are similar to a NZDF medic,6 such as working in an austere or dangerous environment or working in adverse climatic conditions. The clear steps conclude with a ‘what would you do next time?’8 which encourages continual forward thinking (See Figure 1).Employing a narrative style to describe their encounter was encouraged for learners to discover questions they may not yet know the answers to, thus helping to link knowledge and practice, which is especially valuable early in the career.9

A model developed for paramedic use by Willis8 was selected as it is based on pre-hospital contextual elements which are similar to a NZDF medic,6 such as working in an austere or dangerous environment or working in adverse climatic conditions. The clear steps conclude with a ‘what would you do next time?’8 which encourages continual forward thinking (See Figure 1).Employing a narrative style to describe their encounter was encouraged for learners to discover questions they may not yet know the answers to, thus helping to link knowledge and practice, which is especially valuable early in the career.9

Learning is enhanced through using a reflective model as ‘ownership’ of learning rests with the individual as they critique their practice. In addition, clinical time is more than just a race to tick off competencies without further contextual considerations.10,11,12 Guidance and support needs to be provided throughout the reflection process to ensure the portfolio of work is not just a timeline of events or an ‘autobiography’ without any deeper exploration.10,11

Method

Using the reflection on action approach13, a cohort of 14 NZDF MMT learners were interviewed, either in person or by phone, by the author shortly after completing their first and sixth reflection while on their first OJE. All learners voluntarily participated in both interviews (n=14) which lasted about 10 minutes each. Due to the diverse geographic locations it was not possible for the interviewer to visit each learner in person. Consent for the author to approach and interview the learners was obtained by the CO of DTI and the CI of DHS (NZ).Support was also obtained from the Learning Support Manager who facilitated the process and enabled access to the written reflections on completion. Learners could remove themselves at any time without penalty. The author was known to the learners through delivery of a lesson on reflective practice but was not involved in assessing the work or clinical supervision. All responses were confidential and raw data was not shared with any assessors. No identifying patient data was included in the interviews or written reflections.

The author became immersed in all the raw data through repeated reading of the reflections and interviews, listing key words using a coding system similar to that used by Chirema.6 Further analysis of results relating to individual services was not conducted due to the small cohort size, which means it could be possible to identify individual responses.

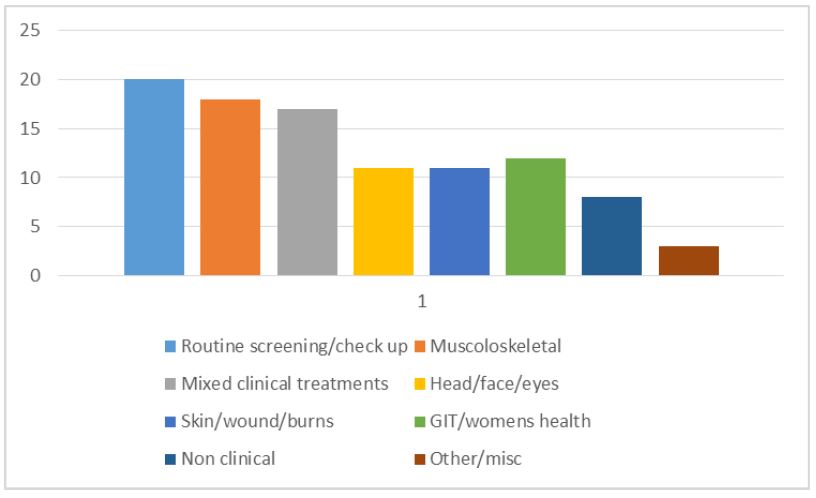

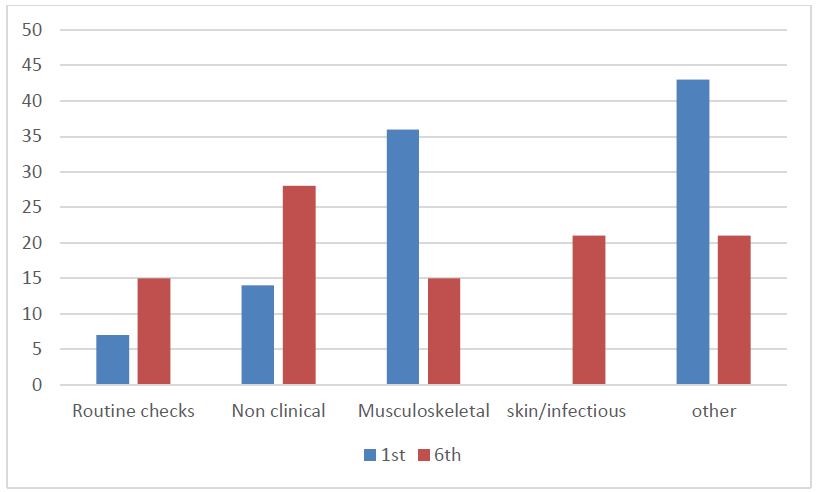

Figure 2: Reasons for MMT reflections during PHC OJE (%)

Results

All 14 of the first cohort of MMT learners completed both interviews, with a 50:50 split of male and female MMT learners (age range of 20-30 years). Two learners already had a prior health qualification, most were school leavers and some had prior work experience before joining the military.

A total of 84 reflections (six per learner) were completed throughout the 12-week OJE, covering 37 different types of reasons All reflections were submitted in a written format using the supplied template. The range of reasons for all 84 reflections is summarised in Figure 2.

Routine screening covers pre-deployment vaccinations, regular check-ups and taking blood samples post deployment. The mixed clinical treatments include skills like suturing, helping the medical officer with minor operations, wound dressings and coughs and cold. The non-clinical reasons included some ethical experiences, documentation errors, and communications with senior personnel, privacy and consent. Other encounters included teaching activities.

The First Reflection

First reflection Questions

What have you learnt from doing the first reflection?

How do you think the reflection has guided your future practice?

What was the hardest thing about doing it?

Twenty broad ‘themes’ of data were identified. These were then further clustered together by the researcher to identify similarities and differences (as per Figure 3).

What did you learn from doing the first reflection?

All felt the reflections helped put experiences into context; however, some identified that it was hard to put their thoughts down into words and weren’t sure what was expected of them. Around half of the responses related that doing the reflection helped to “slow down” thinking and highlighted areas for improvement by “learning from mistakes or errors”. These are indicative snapshots:

“…take a step back…helps to learn to do better and get a different perspective…”

“…found them difficult to do…don’t like talking/ writing…but found that doing them helped with the process and to focus the mind”

How has it guided your future practice?

All indicated increased confidence and knowing what to do “next time” and the need to “think more” to highlight what needs “improving”. Several noted they felt it gave them confidence to “stand up for the patient” or their “own knowledge”. Several noted they could already see the benefit to their future study as it provides a summary to refer back to. One noted the reflection helped them to:

“…not be too complacent…or to have tunnel vision…”

Another noted that doing the research gave them:

“…more knowledge about what to do, more confidence to build up…”

What was the hardest thing?

Several found it hard to “put their thoughts into words” but as already stated no one chose to submit a visual or audio reflection. Three of the learners felt the process was ”easy” as long as they were disciplined to complete them in the right time frame. Over half the learners found it hard to find appropriate literature to support their reflection, despite ready access to online academic databases and support from staff.

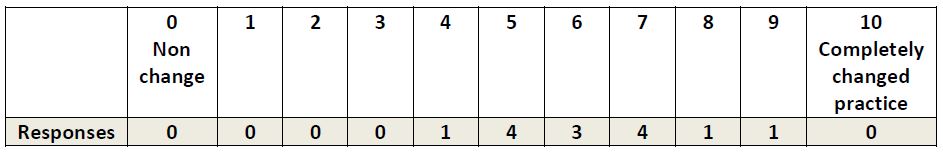

Table 1: Visual Rating Scale used to Self-Rate Confidence by MMT Learners after their 6th Reflection

The Sixth Reflection

Sixth Reflection Questions

How do you feel you have changed from the first to the sixth reflection? (practice, confidence and knowledge)

What have you learnt about yourself through doing the reflections?

On a 0-10 scale, how much do you think doing the reflections has added to your overall confidence?

All interviews (n=14) were conducted during the last week of their 12 weeks of OJE after the sixth reflection had been completed. All learners were based in a different location to their first reflection. Three interviews were conducted in person and the remainder by phone.

How do you feel you have changed in practice, knowledge and confidence?

Eleven broad themes were identified with increased confidence reported by 71% and improved clinical knowledge reported by 64%. Other themes related to improving such as improving the efficiency of the clinical consult and looking for correlations between the clinical situation and the literature. Continual self-improvement and ways to do better or learn more remained as general themes. This is an indicative snapshot:

“…I feel like they flowed more easily and didn’t get writers block, easier to write and understand more… since able to reflect more learn from mistakes…now wanting more in depth…”

What have you learnt about yourself through doing reflections?

The responses ranged from very brief to very detailed with more than half realising in the end they still had a lot to learn, even though they were feeling more confident in their abilities. They also recognised the potential to make mistakes and to remain vigilant to this possibility. Some found the physical act of writing and researching helped them to retain information for future use. One learner intentionally made her reflections more detailed than required so they would become a form of ‘study notes’ for future use. Several noted again they needed to slow down and think these through as they realised most of their reflections were based on errors being made through rushing. Several commented on their improved ability to collaborate and communicate with other team members in a more confident way.

How much has doing the reflections added to overall confidence?

Learners were asked to self-identify how much they felt doing reflections had increased their confidence using a simple 0-10 Scale.

The mean score across all 14 learners was 6.39/10 with a range of 4-9.5.This supports the notion that the learners valued the contribution to their learning; however, a couple did note it was only part of the learning as they felt that actually seeing patients and learning from their supervisors also contributed significantly to their confidence, possibly more than doing the reflections.

Finally, as with the first reflection, learners were invited to add any comments. They all felt doing the reflections were beneficial and they could see the value, whereas at the beginning some weren’t so sure. All felt that doing six reflections in a 12-week period was just the right amount of workload. They saw them as valid learning experiences, “pulling apart” and “learning from mistakes” and “increasing self-awareness”. One noted it was great to be using such a tool so early in her career so she could see how to do more research in the future.

“…they weren’t as awful as first thought…”

‘…At beginning couldn’t see how they would help… but they haven’t only increased my own confidence…I have realised others have gaps…”

Discussion

Figure 3 summarises the clusters of reasons between the first and sixth reflection. Conclusions cannot be drawn from such a small group of learners or comparisons made between services or the NZDF as a whole based on these results. Further investigation of future reflections may provide more data to draw comparisons from. The types of reasons learners completed reflections on during the first and sixth reflections compared to collectively over the whole time could be due to any number of reasons. The first and sixth reflections provide a snapshot of that time period only.

The findings of this study have certainly supported the value of including reflective practice early in the NZDF Medic’s learning and continuing through their future OJE’s in all settings. While it may seem

intensive to complete, time is available and as long as the learners are disciplined to complete within the allocated timeframe there should not be any hindrance to their completion. Others have noted similar issues and go further to state that “reflection is a prerequisite for learning in the context of real practice” .11(p1231) Further analysis could have been completed through a more detailed interview process, using the ‘sense making’ approach as used by Teekman13, whereby the data is drilled further and gaps recognised where specific interactions between patient and health care professional are being explored. This approach would require face-to-face interviews lasting approximately one hour per interview.13

Some responses had an element of ethics such as challenging a superiors’ practice, patient confidentiality and incorrect documentation being completed. While these issues are also experienced within a civilian context, the military context adds a further layer of complexity which could be explored further through the reflective practice model. This duality of conflict of ethics and confidentiality has been examined by various authors within different military contexts;15,16 however, further discussion is beyond the scope of this project.

Learners mentioned the value in the feedback received from clinical supervisors even though some indicated there were delays in getting feedback as part of the criteria for the reflection. This step should not be omitted as the importance of guided supervision with reflective practice, especially so early in a clinical career, cannot be emphasised enough. They need to be conducted in an environment which legitimises and values the use of reflection as a learning strategy.1 Brookfield10 talks about using four lenses as part of reflective practice, with the inclusions of colleague’s experiences as part of the critically reflective lens process.10

Figure 3: Types of reasons for 1st and 6th Reflections (%)

Conclusion

This retrospective study explored the value of including reflective practice as a form of assessment in the new tri-service NZDF medic training which was implemented in in early 2017.All on job learning is completed within military environments and for the first time the use of a reflective practice model was incorporated into the summative assessment while on OJE.

The first cohort of 14 NZDF Medic learners were interviewed after their first and their sixth reflective practice while on their first PHC OJE. They were asked to comment on how they found using the reflective practice model and what it contributed to their learning. In all cases the model and process were seen as positive experience with all learners believing they have learnt from it. The model will continue to be used in further NZDF Medic training with some minor adjustments according to the context.

Corresponding author: Wendy Maddocks wendy.maddocks@nzdf.mil.nz Authors: W Maddocks1

Author Affiliations: 1 New Zealand Defence College