Abstract

Background: The Australian Defence Force (ADF) Adaptive Sports Program offers participation in recreational and competitive sports to wounded, injured or ill veterans to support rehabilitation, recovery and social reintegration. There has been limited research on the impact of sport participation on the physical and mental health and wellbeing of current and former serving ADF veterans.

Purpose: This study was designed to investigate the effects of adaptive sports program participation on individuals’ physical and mental health and wellbeing.

Material and methods: Ethics approval was granted from the Departments of Defence and Veterans’ Affairs Human Research Ethics Committee. A survey was sent to 210 ADF Adaptive Sports Program participants in training camps for preselection for the Invictus Games and Warrior Games 2018–2020. Survey questions invited participants to reflect on their involvement in the program over the previous 2 years.

Results: Responses were received from 29% of program participants. Among the 60 respondents, 78% reported greater engagement in physical activity after participation, and 89% reported that they had experienced a positive effect on their rehabilitation pathway.

Conclusion: These preliminary findings demonstrate that the Adaptive Sports Program increases physical activity and supports rehabilitation, recovery and reintegration for engaged participants competing in local and international events. However, further research is needed to identify outcomes in the wider group of program participants and confirm that the program is an effective strategy for supporting wounded, injured and ill veterans.

Keywords: wounded, injured and ill defence personnel; adaptive sports; physical activity; mental health; wellbeing; rehabilitation, recovery; reintegration.

Conflict of interest: Anna Lewis is a Specialist Reserve Physiotherapist Officer in the Royal Australian Air Force and receives wages for duties as Principal Research Investigator for the ADF Adaptive Sports Program. There are no other competing interests relevant to the writing and submission of this report.

Introduction

In the Australian Defence Force (ADF), there are many positive outcomes and intangible benefits acquired during military service. Life in the military has a positive effect on the wellbeing of the vast majority of serving personnel. However, defence personnel may sustain both mental and physical injuries due to the unique nature of their service. Of the approximately 6000 personnel discharged from the ADF each year, an estimated 18% are discharged for medical reasons.1

Wounded, injured and ill ADF veterans can experience loss of identity, self-esteem, occupation and social connection after transitioning from Defence. The Australian Government Productivity Commission noted in its 2019 inquiry report1 that ‘[W]hile most ADF members successfully transition and quickly re-establish civilian lives, some struggle to address the challenges they experience when they leave the military’ and that ‘sometimes the impacts of service do not become apparent until many years after discharge’. The inquiry recommended that Australia’s veteran support system should be ‘more focused on wellness and ability (not illness and disability)’.1

The Productivity Commission findings are supported by another review that notes the ‘type, intensity and duration of service, along with the transition from full-time military to civilian life, may have a negative effect on veterans’ wellbeing’.2 These consequences, coupled with an increasing population of veterans, necessitate greater attention to the unique needs of veterans’ physical, mental and social wellbeing through transition to civilian life.2 Focusing on these attributes is consistent with the World Health Organization’s definition of health as a ‘state of complete physical, social and mental well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.3

Physical activity is increasingly promoted in the rehabilitation of wounded, injured and ill defence veterans because of its physical and mental health benefits. Documented benefits include increased overall health, mood, energy levels and social engagement,4 weight loss among the overweight and obese,4 and behaviour changes (e.g. smoking cessation, reduction in alcohol use and reduction in angry outbursts).5 Veterans also report important benefits of motivation, reduction in pain levels, and feelings of safety and connection during group exercise programs, due to the camaraderie experienced when engaging in a group.5

Adaptive sports are physical activities and sports either purpose-designed for people with a disability or modified to accommodate people with a disability and their different ability levels while maintaining the integrity of the original sport.6,7

Since World War II, adaptive sports programs have been designed for the rehabilitation of wounded, injured and ill service members returning from combat, focusing on those with spinal cord injuries or amputations.6-8 In the USA, the number of adaptive sports programs offered by the US Department of Veterans Affairs and community-based organisations increased in the early 2000s, in response to high rates of physical disabilities and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among military service people returning from conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.9

Reported benefits of adaptive sport for participants include building social networks, experiencing success, opportunities to positively compare themselves with others without disabilities, and a greater sense of normalcy.6 Participation in adaptive sports has been demonstrated to improve quality of life in people with a range of disabilities, improve self-esteem, athletic identity and self-efficacy among people with spinal cord injuries, and improve balance in people with visual impairment.8

Among wounded, injured and ill veterans, participation in adaptive sports has been associated with significant reductions in total mood disturbance, tension, depression and anger, and a significant increase in vigour.9 A study of US combat veterans with traumatic amputations sustained during military deployments between 2003 and 2013 found that those who participated in adaptive sports programs were more likely to report they enjoyed a meaningful life than those who did not participate.8 Improvements in depression, sleep and quality of life have been reported among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) participating in physical training,10 while scuba diving has been associated with a reduction in social dysfunction and depressive symptoms among ex-military amputees experiencing comorbid anxiety and/or chronic psychological adjustment disorders.11

The ADF Sports Cell (ADFSC) was established in 2018 under the ADF Joint Capabilities Group.12 The ADFSC provides the governance and structure to ensure integrity, transparency and accountability of the ADF Adaptive Sports Program, alongside the Conventional and Pacific Sports Programs. The Director-General ADF Sport commands the three programs through a program lead in each program who develops policy, objectives and their program’s strategic direction.

Preceding this, the ADF Adaptive Sports Program was established in 2017 in response to the recognition that sport has a ‘multiplying’ effect on the recovery, rehabilitation and reintegration of wounded, injured and ill current serving veterans through a holistic and therapeutic approach. The ADF Adaptive Sports Program partners with Veteran Sport Australia, established as a legacy organisation following the Invictus Games in Sydney 2018,13 and other organisations, and involves a wide range of sports within participants’ communities. The program is designed to integrate the support systems of health, sport and social engagement to help wounded, injured and ill current and former serving personnel to succeed in their recovery and rehabilitation. The ADF recognises that participation in sport both supports physical and mental health and helps the Australian community develop a better understanding of the challenges faced by wounded, injured and ill veterans, particularly during the transition to civilian life.

This preliminary research study aims to provide insight into the effects of ADF Adaptive Sports Program participation on individuals’ physical and mental health and wellbeing. This understanding will support the development of appropriate programs for wounded, injured and ill serving and former serving veterans, assist the program to prioritise appropriate resources to maximise benefits for participants, and inform further research.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study investigated health and wellbeing outcomes of participation in the ADF Adaptive Sports Program by wounded, ill and injured veterans from 2018 to 2020 through a retrospective survey. Consistent with the Roundtable of Australian Veterans’ Ministers, the term ‘veteran’ with respect to the program is defined as current and former serving ADF personnel who have served at least one day in the ADF.1

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted from the Department of Defence and Veterans’ Affairs Human Research Ethics Committee on 27 June 2019 (Protocol Number 129-9). An amendment to permit the researchers to obtain free-text answers from participants was approved on 27 May 2020.

Study personnel

Veterans who attended program events from 2018 to 2020 were invited to participate in the study. Wounded, injured and ill veterans who have been, or will be, discharged from the ADF due to a medical condition are eligible to participate in the ADF Adaptive Sports Program. Events included Invictus Games (Sydney 2018), the planned Hague 2020 games (postponed to 2022), Warrior Games USA (Colorado Springs 2018, Florida 2019) and domestic training camps for preselection. All participants (n=210) in these events were invited to enrol in the study.

Survey questionnaire

A survey was designed to evaluate the effects of participation in the Adaptive Sports Program on health and wellbeing outcomes.

Part 1 consisted of 22 multiple-choice questions in a simple format that could be completed on a computer or mobile phone via the Qualtrics XM online survey platform (https://www.qualtrics.com/au).

Five questions collected information on serving status, gender, service, age at date of proposed discharge and number of deployments undertaken while actively serving. Six questions asked participants about their level of engagement in the ADF Adaptive Sports Program, their subjective evaluation of their rehabilitation progress while involved in the program, and their intention to continue participating in the program and other partnership programs such as Veteran Sport Australia.13 These questions used a Likert scale. The remaining 11 questions asked about activities that promote or maintain health and wellbeing, including exercise, eating, social interaction and leisure for personal health. These questions were modelled on the Health Promoting Activities Scale (HPAS).14,15 The HPAS has been validated in a large population of Australian women who care for a child with a disability or have a typically developing child. The HPAS has strong correlations with mental health14,15 and physical activity.16 Due to the unavailability of a scale validated in a military population, the HPAS was adapted for this descriptive study. The complete survey can be viewed in Table 1.

Part 2 invited free-text responses to two topics: ‘What impact, if any, has the Adaptive Sports Program had on your rehabilitation pathway?’ and ‘Please provide suggestions on how the Adaptive Sports Program could assist the rehabilitation of wounded, ill and injured (WII) veterans’.

Table 1. Survey questions

| Question | Responses choices |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Are you a serving or ex-serving Australian Defence Force member? | Current serving member / Ex-serving member |

| What is your gender? | Male / Female / Identify as other / Prefer not to answer |

| Which service do you belong to? | Royal Australian Air Force / Royal Australian Navy / Australian Regular Army |

| How many deployments have you served on? | None/One/Two/Three or more |

| At what age will you/or did you discharge from the ADF? | 18–24 / 25–34 / 35–44 / 45–54 / 55 and older |

| Change in physical activity and rehabilitation | |

| How much has your engagement in physical activity/ training changed since becoming involved in the Adaptive Sports Program (ASP)? |

Much more than prior to the ASP / Somewhat more than prior to the ASP / No change / Somewhat less than prior to the ASP / Much less than prior to ASP |

| Since participating in the Adaptive Sports Program, to what extent have you been involved in a community-based sports program? |

Much more / Somewhat more / About the same/Somewhat less / Much less |

| What effect has your involvement in the Adaptive Sports Program had on your rehabilitation from injury/illness? |

Extremely positive / Somewhat positive / Neither positive nor negative / Somewhat negative / Extremely negative |

| Future participation in adaptive sports | |

| How likely are you to reapply for Adaptive Sports Programs in the future? e.g. Invictus Games, Warrior Games |

Extremely likely / Somewhat likely / Neither likely nor unlikely / Somewhat unlikely / Extremely unlikely |

| How likely are you to approach organisations (e.g. Veteran Sport Australia, local RSL,* Soldier On,† or Mates for Mates†) to be involved in the Adaptive Sports Program? |

|

| How likely are you to recommend the ADF Adaptive Sports Program to other current or ex-serving ADF members? |

|

| Health and wellbeing self-care behaviours and social engagement | |

| How often do you engage in personal health care tasks of planning to eat healthy food/drinks? |

Once or more a day / 2–3 times a week / Once a week / 2–3 times a month / Once a month / 1–3 times a year / Never |

| How often do you engage in a physically active recreational pursuit that you do alone? |

|

| How often do you engage in a physically active recreational pursuit that you do with other people? |

|

| How often do you engage in spiritual or rejuvenating personal time? |

|

| How often do you engage in social activities with people who are important to you? |

|

| How often do you take time out for yourself to spend time as you wish? |

|

| How often do you engage in a quiet, physically inactive leisure pursuit that you do alone? |

|

| How often do you engage in a quiet, physically inactive leisure pursuit that you do with others? |

|

| How often do you engage in social activities with people who are supportive towards you? |

|

| How often do you engage in personal health care tasks of following an exercise program? |

|

| How often do you engage in any other personal health care tasks? |

|

* Returned and Services League of Australia; † Soldier On Australia, and Mates4Mates are charities supporting serving and former serving veterans and their families

The order and format of questions have been adjusted, and question group headings added for publication. Terminology for self-care behaviours adapted from HPAS.16

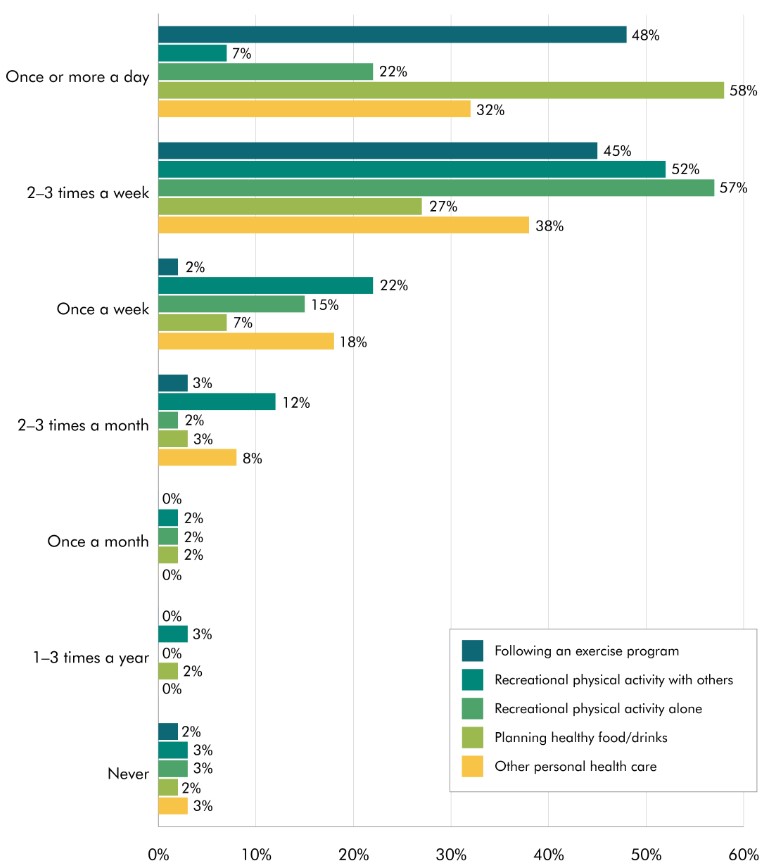

Figure 1. Items adapted from the Health Promoting Activities Scale – self-care behaviors, physical health and activity (n=60)

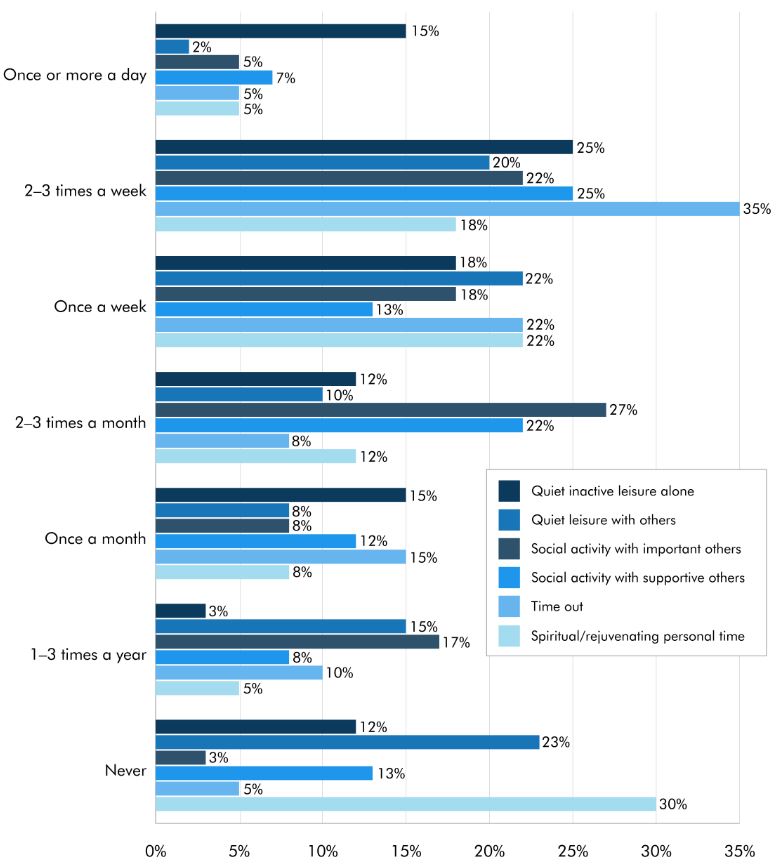

Figure 2: Items adapted from the Health Promoting Activities Scale – self-care, social activity and mental health (n=60)

Analysis was performed on aggregated de-identified responses and presented as frequency distributions (Figures 1 and 2). Responses received for part 2 were collated according to common themes.

Survey process

In September 2019, 210 Adaptive Sports Program participants were invited by email to participate in the research survey and were given an information and consent form explaining the aims of the study and how the data would be used. Enrolment in the survey was voluntary. In accordance with ethics requirements, each participant’s information and consent form was signed by both the study participant and the Principal Research Investigator, then filed in a secure defence electronic filing system with all study correspondence.

Participants were invited by email to direct any queries or anxiety about the study to either the Principal Research Investigator, the Head Coach or the Director-General ADF Sport, whose contact details were provided.

Those who provided written consent to participate were sent a link to the online survey (Part 1). Reminders inviting participation in the study were sent in January and April 2020, with a closure date of 1 June 2020. The raw data report of de-identified responses was extracted from Qualtrics XM on 15 June 2020.

Following an amendment to ethics approval on 27 May 2020, a further survey (Part 2) was sent to those who had provided signed consent to participate in Part 1.

On completion of the research study, participants who indicated they would be interested in the study outcome will be given the opportunity to review the study results.

Results

Survey Part 1

Of 60 participants (29% of eligible participants) who provided consent to participate and responded to the first survey, the majority 78% (n=47) were male (Table 2). Sixty-seven per cent (n=40) were former serving members, and 68% (n=41) will transition from the ADF under 45 years. The majority 60% (n=36) were from the Australian Regular Army (ARA), with 23% (n=14) from the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and 17% (n=10) from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). A greater proportion of participants had served on three or more deployments, 45% (n=27) compared to no deployments 27% (n=16).

Responses measuring the extent of change in engagement in physical activity/training after participation in the ADF Adaptive Sports Program (Table 3) showed 47 participants (78%) engaged more: either ‘much more’ than before the program 40% (n=24) or ‘somewhat more’ than before the program 38% (n=23). Only one participant (2%) reported that they engaged in physical activity ‘much less’ than before the program. Significantly, 57% of participants reported an ‘extremely positive’ effect on rehabilitation from injury/illness through participation in the program and 32% reported a ‘somewhat positive’ effect. Most participants (61%) reported greater involvement in a community- based sports program: 14 (23%) reported ‘much more’ involvement and 23 (38%) ‘somewhat more’ involvement, while 19 participants (32%) reported ‘about the same’ involvement.

Results for the likelihood of reapplying for adaptive sports programs in the future (Table 4) showed 86% positive responses: 41 (68%) reported being ‘extremely likely’ and 11 (18%) ‘somewhat likely’. Only three participants (5%) reported being ‘extremely unlikely’ to reapply for participation. Similar results were reported for likelihood of approaching other support organisations, (e.g. Veteran Sport Australia) to be involved in the program, with 85% positive responses: 32 (53%) participants reported being ‘extremely likely’ and 19 (32%) ‘somewhat likely’. Only 4 (7%) participants reported they were ‘extremely unlikely’ to approach other organisations. Ninety- two per cent of participants reported they were likely to recommend the ADF Adaptive Sports Program to other veterans: 51 (85%) were ‘extremely likely’ and 4 (7%) ‘somewhat likely’. One participant (2%) reported they were ‘extremely unlikely’ to recommend the program.

Responses to the questions adapted from the HPAS on post-program self-reported health and wellbeing self-care behaviours and social engagement are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The majority of participants reported a high level of self-care on all measures, including exercise: 29 (48%) participants reported that they followed an exercise program at least daily, and another 27 (45%) 2 to 3 times per week.

Survey Part 2

Eight (13%) of the 60 participants who consented to the study responded to the second survey, which invited free-text responses. One survey was blank and therefore void. There were no responses to question 1 (impact of the program on individuals’ rehabilitation).

Table 2. Demographics of study participants (n=60)

| Service status | Current serving veterans 20 (33%) |

Former serving veterans 40 (67%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female 13 (22%) |

Male 47 (78%) |

|||

| Service | Royal Australian Air Force 10 (17%) |

Royal Australian Navy 14 (23%) |

Australian Regular Army 36 (60%) |

||

| Deployments | None 16 (27%) |

One 10 (17%) |

Two 7 (12%) |

Three or more 27 (45%) |

|

| Age at discharge (years) |

18–24 0 (0%) |

25–34 18 (30%) |

35–44 23 (38%) |

45–54 11 (18%) |

55 and over 8 (13%) |

Table 3. Changes in physical activity and rehabilitation (n=60)

| Survey question | Response n (%) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much has your engagement in physical activity/training changed since becoming involved in the Adaptive Sports Program (ASP)? |

|

||||||||||

| Since participating in the Adaptive Sports Program, to what extent have you been involved in a community-based sports program? |

|

||||||||||

| What effect has your involvement in the Adaptive Sports Program had on your rehabilitation from injury/illness? |

|

Table 4. Likelihood of future participation in adaptive sports (n=60)

| Survey question | Response n (%) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How likely are you to reapply for Adaptive Sports Programs in the future? e.g. Invictus Games, Warrior Games |

|

||||||||||

| How likely are you to approach organisations (e.g. Veteran Sport Australia, local RSL,* Soldier On,† Mates for Mates†) to be involved in the Adaptive Sports Program? |

|

||||||||||

| How likely are you to recommend the ADF Adaptive Sports Program to other current or former serving ADF members? |

|

* Returned and Services League of Australia; † Soldier On Australia, and Mates4Mates are charities supporting serving and former serving veterans and their families

Responses to question 2 (suggestions for how the Adaptive Sports Program could assist rehabilitation of wounded, injured and ill veterans) ranged from one to several points. Themes included improving access to sporting activities and training equipment (4 participants)—for example, through subsidies or grants, placing greater emphasis on community sporting involvement (3 participants), and setting up a mentorship system (2 participants). Other suggestions included establishing links to health providers (e.g. nutritionists), and changes to program organisation such as competitive categories and selection criteria. One participant proposed that the selection process should place a greater emphasis on the program’s potential to enhance an individual’s rehabilitation.

Two responses encapsulated the aims of the program:

Place more emphasis on the activity; participation and connections are more important than winning or being the best at something.

The program is about recovery and not winning medals…

Some respondents also commented on the benefits of adaptive sports in general or the ADF Adaptive Sports Program:

Having a team of other wounded veterans playing adaptive sports gives a safe place to talk to each other.

Adaptive sports give better chances of a level base line so despite variations of injury you can play the sport at the same level…

Adverse events

Throughout the conduct of this study, no adverse events occurred as a consequence of participation in this research study, as confirmed by regular interim reports submitted (as per the ethics guidelines) to the Departments of Defence and Veterans’ Affairs Human Research Ethics Committee.

Discussion

This survey was the first formal evaluation of the ADF Adaptive Sports Program. The findings are consistent with previous anecdotal feedback provided to staff at camps: that engagement in adaptive sports supports the rehabilitation of wounded, injured and ill veterans through stronger connections to their community.

Evidence supports the importance of the collective interconnection of the three key domains of physical, mental and social health and wellbeing.2 Issues in one or more of these domains, by default, become risk factors for issues in other domains. For example, Adaptive sports programs provide opportunities for health-promoting activity and help veterans experience the physical, emotional and social benefits of sport to enhance rehabilitation, recovery and reintegration.

A key objective of an effective transition from military to civilian life is the restoration of health and wellbeing through timely and effective rehabilitation, support and social integration.1

The findings of this preliminary study validate the program by demonstrating that, while it continues to evolve, 89% of participants reported a positive influence on their rehabilitation. Recommendations for program improvement include further engagement with stakeholder and partner organisation Veteran Sport Australia, which provides broader access to national programs to support wounded, injured and ill veterans and promotes their participation in sport within the community. Implementing and embracing a ‘battle buddy’ culture4 within community sport has the potential to provide physical and emotional support for participants and their families.

Targeted program promotion to veterans discharging from ADF, particularly the 18% discharging for medical reasons,1 with timely follow-up at designated intervals (e.g. at 3, 6 and 12 months), has the potential to engage veterans early in their transition and rehabilitation pathway. The ASP requires appropriate resources, financial and personnel, to support this. Providing veterans with funding through subsidies and grants could also facilitate engagement in community sport. Ongoing participation in community sport should precede enrolment in key events such as Invictus Games or Warrior Games.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous survey-based studies evaluating adaptive sports. A recent cross-sectional survey-based study by Lee-Hauser17 found that participation in a large organised adaptive sports program, such as the US National Veterans Wheelchair Games, had positive associations with daily function, quality of life and community participation. Funding for further research evaluating the impact of community sport participation on the physical and mental health and wellbeing of ADF veterans is required. In particular, community sport not associated with major event selection should be targeted. An overarching research strategy plan developed between ADF and stakeholder organisations is critical to achieve better outcomes for ADF veterans.

Evidence gaps

Other authors have noted important gaps in the evidence supporting adaptive sports for mainstream populations, particularly for wounded, injured and ill current and former serving veterans. A recent systematic review7 noted that evidence for the effectivenessofadaptivesportsactivitiesandprograms was limited to few sports and few populations (mainly people with PTSD, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis or cerebrovascular accidents), mainly from observational studies enrolling selected individuals. The same review noted that important outcomes such as self-esteem/perceived competence, community integration/social functioning and employment were infrequently reported.7 Few studies have investigated factors affecting the effectiveness of adaptive sports activities or programs (e.g. frequency of duration of participation, demographic factors, type of sport or severity of disability).7 Few studies have reported outcomes of adaptive sports programs for wounded, injured and ill defence services populations.17,18 The findings of a recent study of US veterans participating in a sports clinic suggest that short-term benefits on depression, anxiety, social functioning and mood are lost at 3-month follow-up, suggesting that longer- term engagement in physical activity is needed.18

Limitations of this study

A known limitation of this study is selection bias. The study participants were invited to participate retrospectively, and, therefore, the responses received may not be an accurate representation of all wounded, injured and ill veterans who participate in the ADF Adaptive Sports Program. A recent systematic review noted that this was a common shortcoming of research in this field, given that most evidence is from observational studies of people who had agreed to participate in programs.7 Future surveys assessing the program should be conducted prior to team selection to avoid influencing or distorting responses.

Part of this survey was based on HPAS, a research tool that is psychometrically sound and clinically relevant but was validated for use in another population.14 A validated research tool for assessing health and wellbeing outcomes developed for wounded, injured and ill personnel is needed for comparative research in this population.

The second free-text survey was undertaken in response to informal and unsolicited written feedback from program participants, which could not be published without ethics approval. We expected to receive similar comments, which would be available for collation and analysis to guide future program decisions. The low response rate and the unexpected lack of response to the question about the impact of the program on individuals’ rehabilitation might reflect participants’ loss of engagement due to the time lag between the two phases, concerns that they might be identifiable from their responses, or disinclination to allow personal experiences to be published.

Conclusion

These preliminary findings demonstrate that the ADF Adaptive Sports Program has positive outcomes on physical activity and supports rehabilitation for participants competing in local and international events. The program has an important role for current serving ADF personnel to support rehabilitation, recovery and reintegration. Further research is needed to identify outcomes in the wider group of program participants to ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of the program.

Corresponding Author: Anna Lewis, anna.lewis1@defence.gov.au

Authors: A Lewis1,2,3

Author Affiliations:

1 ADF – ASFSC Adaptive Sports Program

2 RAAF – 1EHS RAAF Base Amberley

3 Sports Focus Physiotherapy