It will be recalled in the first of this two-part article,1 that this year is the centenary of Australia’s involvement in the Boxer Rebellion. With over 550 men from NSW, Victoria and South Australia, it was the largest ever deployment by the colonial naval forces. Each contingent had it’s on medical personnel and the aim of this two-part article is to tell their story. The first described the SA contingent and their ship Protector, while this one relates the story of the NSW and Victorian contingents.

Introduction

At the risk of repeating old ground, the Western powers extended their Chinese trade against strong resistance throughout the 19th century. The aim of the I He Tuan or “Righteous Harmony Group” (corrupted by Westerners to I He Chuan or “Righteous Harmony Fists” – hence ‘Boxers’) was to kill all foreigners in China. Although lacking a specific leader, the Boxers shared the inculcation of invulnerability to foreign weapons, the battle cry Sha! Sha!” Kill! Kill!”), the use of red shirts as a type of uniform, and the use of complicated, prolonged and highly unpleasant tortures.

The rebellion began in late 1898 with attacks on Chinese Christians. These intensified and by May 1900 the legations at Peking (Beijing) sought military assistance from the international naval forces at Taku (Daku), on the mouth of the Pei Ho (Beo he) River. These forces were beaten back, initiating a two-month siege.

Australian Responses

Australian attention in mid-1900 was on the Boer War and the impending Federation of the six colonies. These received a request for assistance from the British Secretary of State Joseph Chamberlain on 28 June. In response the Royal Navy gunboats HMS Mohawk and Lizard and the cruiser HMS Wallaroo sailed from Sydney on 2 July.

Colonial efforts were characterised by attempts to outdo each other. On 29 June the Victorians offered their gunboat Albert, but instead sent 200 sailors for service ashore. Queensland’s offer of one of their two gunboats Gayundah or Paluma was rejected, but SA’s offer of heir gunboat Protector on 2 July was provisionally accepted three days later. Besides agreeing to release Wallaroo, the NSW government suggested its contingent be used for the other Auxiliary Squadron ships, but instead sent 250 sailors with the Victorians for service ashore.

Like the South Australians, the shore contingents were also dogged by the mismatch between RN and colonial pay rates (1s. 9d. per day for RN able seamen compared with 7s. 6d. for Victorians). After considerable delay, it was agreed the British would pay RN rates with the colonies making up the difference, as per the Boer War contingents.

Recruiting and Deployment

Victorian Navy. The Victorian Navy was the largest and most mature of the colonial naval forces. It had begun in 1855 with the wooden screw sloop Victoria, which saw active service in 1860-1 in New Zealand. Concerns regarding her legal status lead to the British Colonial Naval Defence Act 1865, which provided the legislative basis for colonial naval forces until the inauguration of the RAN in 1911. The 1865 Act authorised the British colonies to raise, train and sustain naval forces for service within their own territorial waters (then only three miles offshore).

This maintained unity of command for the Royal Navy in international waters but meant colonial ships could be charged with piracy for any warlike acts committed outside their territorial limits. For this and other reasons, Protector was commissioned at Hong Kong as a Royal Navy ship for China service. The Act allowed the Victorians to expand their naval forces and by the mid-1880’s they had a small but reasonably efficient squadron to defend Port Phillip Bay.

The three decks line-of-battle ship Nelson was the largest of her kind in Britain when she was built in 1814 but she was never commissioned into the RN, even after her conversion to steam in 1860. Ancient by the time she was permanently loaned to the Victorians in 1867, she remained the Victorian flagship until 1898. On the other hand, the coast defence ship Cerberus was a prototype for all warships until the missile age. Not only was she one of the first warships to dispense with sails, but she was also one of the first to mount her main armament in rotating turrets. Commissioned in 1870, she never left Port Phillip Bay for the next 50 years and on her transfer to the Commonwealth Naval Forces was used as a depot ship until her sale in 1924. Other Victorian Navy ships included the gunboats Victoria and Albert, the torpedo boats Countess of Hopetoun. Childers, Nepean and Lonsdale and several auxiliaries.

By 1892 the Victorian Navy had 236 regular and 340 ‘casual’ or reserve personnel. The Depression of the 1890’s, however was a desperate time for the Victorian Navy, with Nelson, Victoria and Albert being sold and most of the other ships placed in reserve. Manning was also hard hit, with many permanent service personnel laid off.

Victorian Recruiting. Recruiting for China began aboard Cerberus on 7 July, initially with 87 permanent force personnel from her ship’s company, plus 40 from Port Melbourne and 29 from Williamstown, all under Commander Francis Tickell. As most were ex-RN personnel, the average age was about 35 years and over

75% were married (compared with the Boer War volunteers who were mostly single 22-23-year-old). Kit issues from 9 July took two days and were accompanied by medical examinations by Staff Surgeon 1 Charles Alfred Stewart, aided by Sick Berth Steward2 (SBS) William Stanser Patchett.

So far not much is known about Stewart. He was born on 28 October 1855 and received his licence in midwifery, medicine and surgery from Edinburgh in 1879. In 1883 he was resident surgeon at the Launceston General Hospital and was acting as surgeon to the Tasmanian Light Horse. By September 1885, having moved to South Melbourne, he was already Principal Medical Officer to the Victorian Navy with the rank of Staff Surgeon. He was promoted to Fleet Surgeon on 22 February 1901 (during the deployment) and was transferred to the unattached list on 1 October 1905.

In 1900 Stewart was one of five part-time Victorian Navy surgeons. The others included Honorary Surgeon5 George Thomas Cooke Adams (from Melbourne, commissioned May 1899) and reserve Surgeons Francis Cheetham (from Tasmania commissioned 1884). Harry Paynter Sloggett (from Melbourne, commissioned December 1898) and Edward Johnson Williams (from St Kilda, commissioned October 1893). Of these only Sloggett transferred to the RANR in 1912, having been promoted to Staff Surgeon in September 1906. It, therefore, seems likely Stewart was selected on the basis of his seniority.

During the deployment, Stewart was paid £383 5s. Od. per annum7(£157.6s.6d. in advance) plus imperial pay rates and 4s. 4d. per day field allowance, compared to his usual part-time rate of £41 13s. 4d. per month. On his return home he was also paid 15s. subsistence allowance from Sydney to Melbourne.

The contingent was sworn in at Williamstown on 23 July and moved aboard Cerberus pending the arrival of the transport Salamis. Meanwhile, as could be expected the Victorians engaged in some undignified ‘winding up’ of the NSW government, following delays to the latter’s preparations. NSW Naval Forces. With the RN based at Sydney it is perhaps not surprising that, compared to the Victorians, the NSW naval forces were considered somewhat amateur. The fact that they usually had no ship of their own did little to help their professional standing, either with the RN or the other colonial naval forces.

Sydney had a small RN presence from 1788 until Governor Lachlan Macquarie ended all but occasional visits in 1810. From 1821 the RN detached one ship from the East Indies Squadron to protect British interests in the Pacific. At first lack of dockyard facilities limited these deployments to 12 months but by 1836 the RN had two ships permanently based in Sydney. By 1848 increased hydrographic surveying work and anti-blackbirding patrols lead to an Australian section of the East Indies Squadron. The establishment of a completely separate Australia Station in 1859 resulted from the 1850’s gold rushes and the Maori Wars. The RN maintained the Australia Station until the RAN took it over in 1913.

Apart from a small colonial marine between 1793 and 1829, Sydney’s local defence efforts relied on building forts to defend the Harbour as a response to various war scares. In 1855 Sydney had only one small ketch-rigged gunboat for local maritime defence, which was under Army control and was sold two years later when Fort Denison was completed. Although Captain Francis Hixon established the Naval Brigade in 1863 (commanding it until 1902), it remained firmly land-based at Newcastle and Fort Macquarie (now the site of the Opera House). Even when the colonial torpedo boats Acheron and Avernus were commissioned in 1879. they were manned, not by the Naval Brigade, but by the NSW Torpedo and Signal Corps.

In 1882 the old screw corvette HMS Wolverine was transferred to the NSW government for naval training. Built in 1864, she rarely went to sea and was paid off in 1892, again leaving the NSW naval forces without any ships at all.? Yet even she was manned by the NSW Naval Artillery Volunteers (NAV which seems to have been an upper-class alternative to Hixon’s Naval Brigade. The depression of the 1890’s meant that the Naval Brigade had not had its annual Easter camp in the six years to 1900.

NSW Naval Medical Officers. Although lacking ships by 1900 the NSW naval forces had no less than seven part-time medical officers. Fleet Surgeon Samuel Thomas Knaggs (seniority 1 April 1896) had first been appointed to the NSW Naval Brigade in 187210 and remained active until 1 January 1912.11 He first qualified in Ireland in 1870, before receiving one MD in Aberdeen in 1873 and another in Sydney in 1882. He held several positions, including membership of the NSW Board of Health (1877-82) and editorship of the Australasian Medical Gazette and Australian Practitioner. From 1872 to 1884 he was Honorary Surgeon to Newcastle Hospital and in 1875 was Acting Health Officer for the Port of Newcastle. Knaggs later became Honorary Surgeon at St Vincent’s and Prince Alfred Hospitals, as well as Lecturer on Clinical Surgery at Sydney University. He was also Examiner in Anatomy and Physiology at the Board of Technical Education of NSW from 1887 until 1892.

Knaggs other position in the Department of Public Instruction was interesting, as he was the first medical practitioner to introduce St John first aid training to Australia. In 1881 he obtained permission from St John Headquarters in London to conduct the class and brought back first aid manuals and bandages for the Eveleigh railway workshops in Sydney. This preceded the first official Australian St John organisation formed in June 1883 in Melbourne. Motivated by Knaggs, a committee was formed in 1887 to establish St John in NSW, but it did not formally begin operations until 1891. This did not prevent Knaggs from examining several St John courses at Randwick from 1889, including one aboard HMS Dart. In keeping with the priorities of the time, most of the students were railwaymen, police and firemen, but it also included Sydney’s major industrial concerns, such as the Mort’s Dock Engineering Company.

The NSW Naval Brigade had three Staff Surgeons. Wilfrid John Robert Nickson (seniority 13 August 1898) was first appointed in August 1890, having qualified in Dublin in 1886. In 1900 he was Honorary Medical Officer at Newcastle Hospital. Theodore Mailler Kendall was first appointed in August 1898. He may have been Australian born, having received a BA from Sydney in 1876 before qualifying in medicine and surgery at Edinburgh in 1881. John James Steel was the MO for the NSW Contingent and his background will be related separately.

Surgeon Gregory John Lamb O’Neill qualified at Edinburgh in 1886 and was appointed into the Naval Brigade in August 1898. In 1900 he was Honorary Physician at St Vincents Hospital. Surgeons W.B. Violette and G.D. Hughes were appointed into the NAV in August 1889. Violette qualified at Glasgow in 1881 and had been Visiting Medical Officer to Parramatta Gaol when he was promoted to Staff Surgeon in May 1900. 13 No information on Hughes is available at present. Of these seven medical officers, only Nickson transferred to the RANR with the rank of Fleet Surgeon from 1 June 1912.

NSW Recruiting. Recruiting in NSW began well but quickly dried up when they were advised on

7 July that not only were they to serve ashore but would do so on only 75% of the Victorian pay rate. As a result, three days later there were still only 29 volunteers. The decision to pay Victorian rates was not only driven by a lack of recruits, but by lack of time before the troopship Salamis arrived to pick up both contingents and news of another massacre in Peking on 16 July. By 23 July there were still only 100 NSW Naval Brigade and 70 NAV personnel and the numbers were eventually made up by 24 men who were originally going to South Africa. As these men objected to becoming sailors and the sailors objected to mixing with soldiers, they became the NSW Marine Light Infantry (NSWMLI) – the only marine force in Australian history.

The NSW Contingent also included an Ambulance Party under Staff Surgeon Steel. This had been raised by Nickson at Newcastle four years previously with 10 volunteers (i.e. unpaid) personnel. In June 1900 however, approval had been given to pay them part-time (one acting petty officer at £8 and 10 able seamen at £4 each per annum) and to obtain £31 5s.6d. worth of first aid stores.14 An extra seven men (making a total of 18) were recruited for China on 8s.6d. per day.

AB Hidden later served in WWI with the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force in New Guinea in 1914 and later with the 9t11 Battalion AIF. AB Field’s China Medal is at the Australian War Memorial. Although at least three more men from the Mort’s Dock Ambulance joined the contingent (AB’s McFarlane, Hood and Chester), none did so as ambulance personnel.

The Ambulance Party skills were limited to St John first aid, rather than the more extensive RN curriculum. 8 Knaggs had inspected the Stretcher Party with Steel and Midshipman Black on 27 May 1899. His report states:

“Fourteen men attended their ages were from twenty-two years to thirty-six, they were all of excellent physique and presented a perfect sailor-like appearance their dress accoutrements and appliances were in good condition.

The stretcher drills and exercises were most creditable and having been put through a most searching “Viva voce” examination in “Ambulance work” and “First aid to the Wounded” by Staff Surgeon Steel in my presence, I must say that the replies to questions were most gratifying and satisfactory, and exhibited a thorough and practical acquaintance with ambulance work.

I beg to report that in discipline and knowledge of Ambulance drill and work, the Newcastle Stretcher Party of the NSW Naval Brigade has passed a most creditable inspection and I suggest that a letter to that effect be forwarded to Staff Surgeon Nickson”

In the event, training in preventive health rather than first aid would have proved more useful in China.

John James Steel was born in Millport in Scotland in 1855, the son of the Reverend Dr Steel in Sydney, the brother of the Reverend Robert Steel of Campbelltown, and Mr H. Peden Steel, a solicitor also of Sydney. 15 He received his education at the Universities of Sydney, Edinburgh and Paris, obtaining his licences in medicine and surgery in 1878 at Edinburgh before graduating MB in 1883 and ChB in 1884 from Melbourne. He was Senior House Physician and Surgeon at the Royal infirmary in Glasgow, before practising in Dudley and Birmingham. 4 On returning to Sydney in 1882 he rapidly acquired an extensive practice. A widower with one daughter, he was very proficient in languages and an apt student in literature (particularly Shakespeare). He was first appointed into the Naval Brigade on 1 April 1896 and was promoted to Staff Surgeon on 13 August 1898.10 This rather rapid rise relative to his peers suggests a high level of confidence in his abilities. This is further supported by his selection for service in China, for which he received £500 per annum.

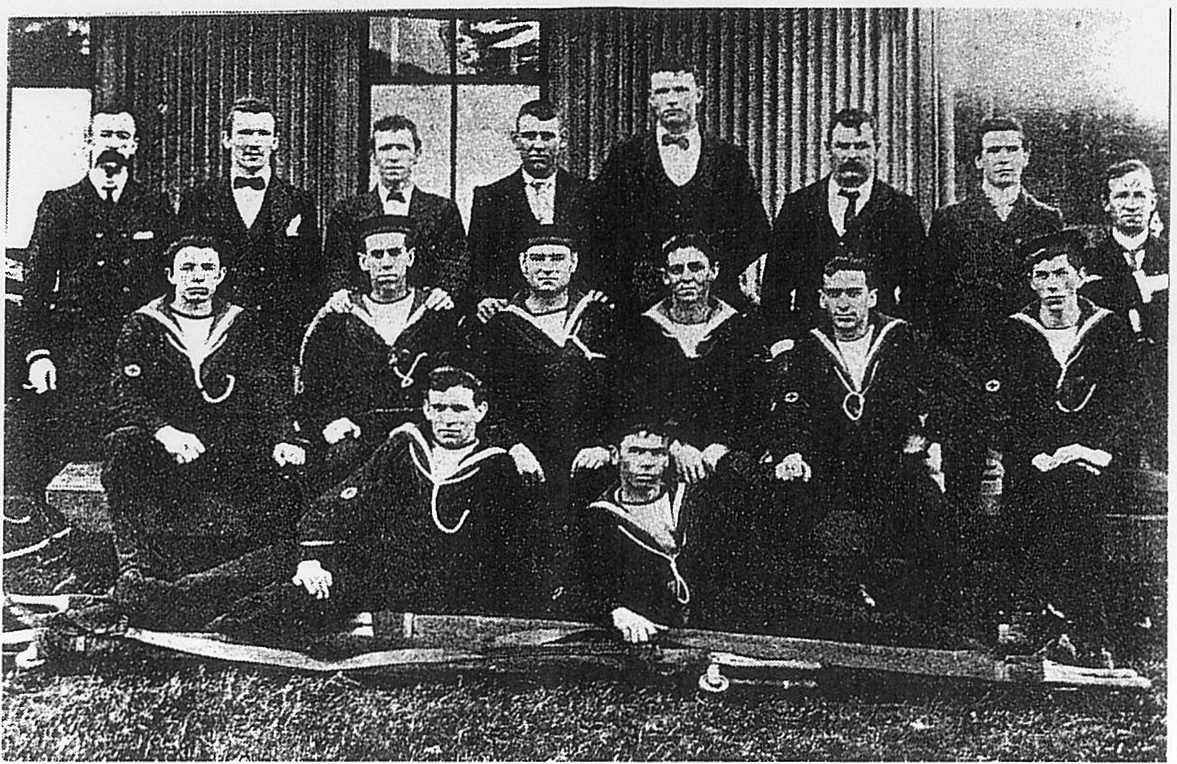

The NSW Naval Brigade Ambulance Corps. Note the top row have ye to receive their uniforms.

Top Row (L-R): AB R.W. Hidden, AB A.E. McDonald, AB C.A. McDonald, AB W. Whitelaw, AB T. Armsby, ABA. Matthews, PO Dispenser S.L.N. Harvison, AB W.I. Maguire

Middle Row: AB G.J. Sale, AB J. Gascoine, CPO H.J. Atkinson, LS H. Connor, AB T. Sippe, AB J.A. Blanchard.

Bottom Row: AB F.J. Pascoe, AB L.G. Field Absent: AB R. Evans. AB S.H. Priest (Courtesy Bob Nicholfs)

Recruiting took place at Fort Macquarie. At 1400 on 28 July the medicals were commenced:

It seems the pass rate may also have been improved by only examining recruits from the waist up. There was however:

Another 14 men were examined by Nickson at Newcastle and passed fit, including Priest. Evans and Sheen of the Ambulance Party (although in the event Sheen remained behind). It seems that the need to ensure large numbers personnel are fit to deploy at short notice has not changed in 100 years.

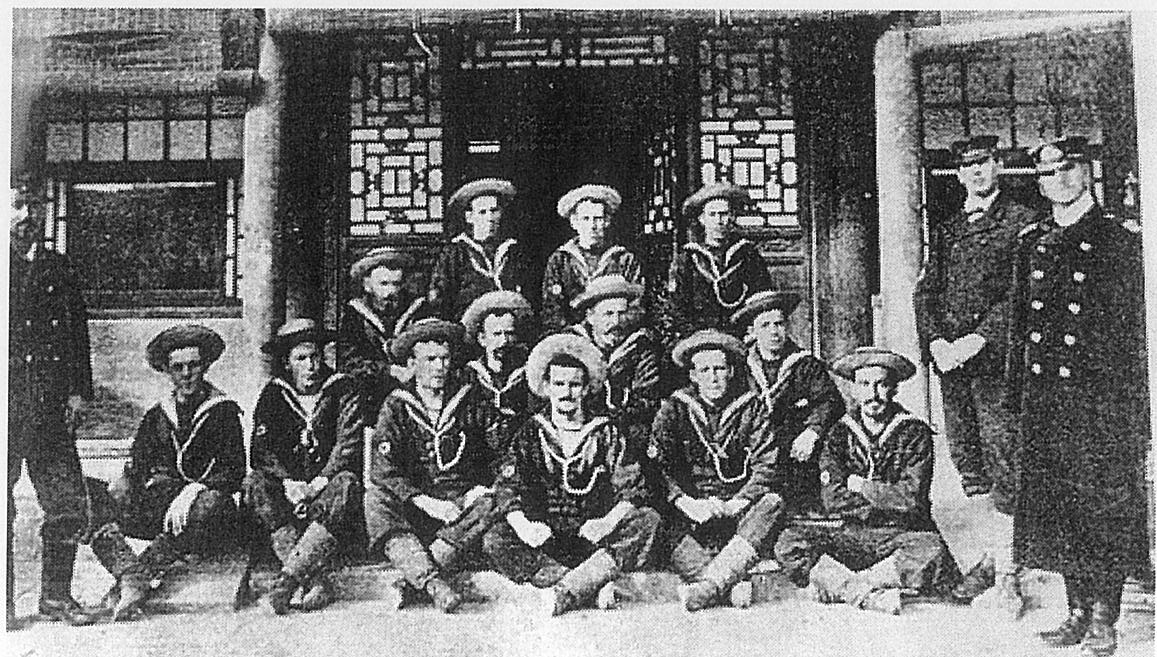

The NSW Naval Contingent Ambulance Party outside their quarters at the Chang-Wang

Palace. The section named their quarters ‘Katoomba Cottage•. Note the Red Cross rate badges on their right arms. Staff Surgeon Steel is on the right. The two men on either side of the sailors could be CSBS Atkinson and Dispenser PO Harvison.

(Courtesy Bob Nicholls)

Demographically, apart from the officers the NSW Contingent was similar to the Victorians. The NSW officers were mostly commissioned reservists with little sea or operational experience, while the Victorians had mainly ex-sailor Warrant Officers. Although Nicholls believed this made little difference once they were in China, differences in casualty rates between the two contingents suggest otherwise. The NSW contingent was commanded by the elderly Captain Hixon as far as Hong Kong, where it was taken over by Acting-Captain Gillespie (in reality a Lieutenant RN loaned from the Auxiliary Squadron cruiser HMS Mildura).

Kit issues for the NSW Contingent were poorly done for lack of time, with the list of officers only being forwarded on 23 July 17 for approval two days later,18 while the Marines were not sworn in until 4 August. 9 There was a series of send-off parties and concerts, including one on 6 August for Steel at which he received a pair of binoculars ‘from a few of his old friends as a mark of the high esteem in which he is held by them’. Last-night predeployment medical routines were maintained when AB Charles Hart fractured his ankle, albeit not from sport but by falling off a tram.

The Deployment. The liner Salamis (4650 tons, or about the same size as a DDG) was requisitioned to transport both contingents. Following her conversion at Garden Island, she sailed on 28 July, arriving in Melbourne next day to load the Victorians in her aft hold. She departed on 31 July and returned to Sydney on 4 August to load the NSW Contingent forward three days later. One NSWMLI member was landed ill before the ship left Sydney. Salamis finally sailed from Sydney on 8 August, after her civilian Chief Steward shot himself the night before.

Modem naval medical officers will easily identify with Steel when his name was omitted from the list of personnel receiving field allowance, leading to a hurriedly scribbled letter from Captain Hixon to correct the ensuing pay error the day the ship left Sydney.7 One wonders how long it took Steel to receive his money.

From this less-than-smooth start, the trip north was reasonably relaxed compared to Protector’s, being limited to daily small arms, machine gun and field gun drills in hot and humid conditions. The Ambulance Party exercised both bandaging and cutlasses (reflecting their somewhat ambivalent pre- 1907 Hague Convention role) as well as performing smallpox vaccinations (later to be a major concern). They crossed the Line on 16 August and arrived at Hong Kong ten days later, where they exchanged guns and equipment to standardise with the RN. Acting Captain Gillespie took over command and despite the allegedly ‘rigorous’ examinations – five men from the NSW Contingent were medically surveyed, four of whom were invalided home. zo

Meanwhile, the Taku forts had been stormed on 17 June, allowing movement upriver to Tsientin1 and Peking. A 20,000 strong international force at Tsientin advanced on Peking from 4 August and relieved the legations 10 days later, ending a two-month siege. The task for several months thereafter became reasserting law and order while preventing another Boxer surge. The Australians’ desire to perform at least as well in China as the Boer War contingents was foiled by the fact that most of the fighting was over before they arrived.

Operations

Initial Movements. Salamis first visited Wei Hai-Wei, (where the British had a 500-bed field hospital and the Americans their hospital ship Maine) before arriving at Taku on 9 September.21 At first consideration was given to the Australians taking over the local forts but on 15 September they instead moved up river to Tsientin where fighting continued. From there, 300 men were sent as part of an 8000-strong force on a forced march to attack the Peitang fort at the entrance to the Pei Ho River. They were told to travel light and did so to the extent of not carrying rations. Lieutenant H.E. Lofts NSWMLI wrote of one village:

This was probably Stewart, as he returned that night to Tsientin. It seems the average MO’s faith in the invincibility of their own immune function is an old problem.

With Stewart’s departure Steel took charge. As men fell out with exhaustion and sunstroke, he was at each man’s side, administering stimulants and giving words of encouragement before doubling back to his own column in a series of running races. A change in plan had the men travelling by lighter, followed by another 18-mile march with no food and bad water. On their arrival at Peitang they found the Russians had captured the fort an hour previously.

By then several stragglers were missing and Steel earned the good wishes of the Victorians by spending the rest of the second night bringing four of them in. He continued this work he collapsed the following morning, to be carried unconscious back to the British hospital at the Gordon Public Hall at Tsientin. Three days later he insisted on returning to camp, where the men apparently gave him an enthusiastic ovation.

With 5men returning by train and the rest on foot, the force arrived back at Tsientin on 22 September. Besides demonstrating the need for a degree of physical fitness for shore service, the whole episode provided valuable experience for the next attack, on Pao-ting fu. One change was to give the MO a horse to improve his mobility.

Meanwhile, the rest of the Australians set up camp on the Tsientin racecourse, near a swamp full of mosquitoes. Poor logistics lead to foraging of supplies (perhaps more accurately described as looting), which continued for much of their time in China (and to an extent fulfilling the main reason to go in the first place). By early October 25% of the men were on the sick list, with dysentery, influenza, ‘fever’ and ‘ague’. These were evacuated via the Gordon Public Hall Hospital to the British hospital at Wei-Hai-Wei. This did not prevent the contingent’s first death (Pte T.J. Rogers NSWMLI) of influenza on 6 October after two days in hospital. He had rheumatic fever during the voyage north and had almost been sent home from Hong Kong, “but recovered considerably and was given the benefit of the doubt”.24 Another nine MLI personnel were left behind due to illness after the NSW contingent moved to Peking. They eventually arrived:

The high proportion of MLI on the sick list (nearly half) is of interest. This episode begs the question of what the Ambulance Party were doing, as it is unclear why these patients were not in the Gordon Public Hall Hospital or the German military hospital at Tsientin. Perhaps they tried to look after their own without the resources to do so. It seems likely that their training did not include managing infectious illness.

Both contingents were assigned to an attack on Pao-ting fu (a city of 200,000 people 120 miles south-west of Tsientin), before taking up garrison duties at Peking for the winter. However, the NSW Contingent was ordered directly to Peking and they departed by boat up the Pei Ho river on 10 October. The move took 10 days and included another 20-sick including three officers, who were moved on a houseboat. Besides the nine men previously mentioned, four men were left behind in the Gordon Hall Hospital and AB Bain was sent to Wei-Hai-Wei to recover from pneumonia By then trading for food had (mostly) replaced looting, although the area had been comprehensively ransacked by other forces. At Peking the Contingent split into three groups, with 53 men at the Legation, 63 at the Llama Temple and the rest (including the Ambulance Party) at a headquarters at the Chang-Wang Fu Palace for guard duties. Notwithstanding the number of sick, the health of the contingent at this time was reported as “fairly good”.

The Victorians prepared for besieging Pao ting fu by commandeering junks and ponies for their equipment, including their 12 pounder guns from Hong Kong. 250 heavily armed men departed on 12 October with another 7250 men, leaving behind Commander Tickell’s servant Boy Albert Gibbs, who died of fever aboard the hospital ship Carthage on 19 October and was buried at sea. The march took 10 days, with cold and wet conditions delaying progress. On arrival on 21 October they were spared laying siege when the city officials surrendered. In fact the whole operation was negated by a French flying column which had reached the city four days previously. Foiled again, the Victorians released missionaries, guarded prisoners found guilty of murder (until they were handed over to the Germans for shooting) and the aforementioned city officials (who were handed over to the French for shooting).

Finding no Boxers in the area, the force returned to Tsientin via their approach route. Disaster was narrowly averted on 5 November when a junk carrying ammunition exploded. Although the ammunition was guarded by members of the Hong Kong Regiment, they could not stop the locals ferreting around for anything useful. Blast injuries and bums predominated, with the Chinese quilted clothing proving particularly flammable. In all there were over 90 casualties with at least 40 killed outright. The junk next to the Victorians had five killed and two wounded. Fortunately, no Victorians were hurt, despite some of them having carried ammunition to the junk just before it exploded. 7

They returned to Tsientin on 7 November, having taken part in innumerable sackings, looting, arson, pillage and executions on the way back, but no enemy contact. With winter almost upon them, the Victorians moved from the racecourse into a go down (storehouse) which became their barracks and headquarters until they left China five months later.

Winter in Peking. The NSW Contingent quickly settled into their quarters. The Legation group guarded banks, provided orderlies for the British headquarters and fired the noonday gun. The Llama Temple group guarded the temple itself, a go down full of loot, and the hole in the city wall made by the Boxers during the siege. The headquarters group supplied guards for the main entrance and 20 men for police duties with officers having magisterial authority over the Chinese. Their justice was rough and ready, allowing large fines, flogging, house raids on suspected Boxers or their sympathisers (allowing more looting) or execution for captured arsonists by shooting. ‘Mission creep’ soon had the Australians setting up municipal authorities for street lighting, cleaning, and later firefighting (usually by pulling down adjacent houses).

Social activities were mostly limited to the officers, who had dinners, horse racing and gunnery competitions, interspersed with numerous parades (including one for Australian Federation on 1 January 1901). For the men there was no wet canteen and the local rice-based firewater was banned. Meanwhile, AB J. Hamilton from Glebe NSW died on 6 November of exhaustion following dysentery, having been left at Tung-chao during the move to Peking from Tsientin. He was buried locally.

Next was Steel himself, who was found dead in his room at 2300 on 10 November. He had been in ill health since the Peitang expedition (presumably a result of his collapse) and had only been discharged from hospital the day the NSW contingent started its move to Peking. He was known to be suffering dysentery and insomnia, for which he was taking a ‘sleeping draught’ and at the inquiry into his death it was assumed he had taken an accidental overdose of chloral hydrate. He was buried with full military honours in a temporary graveyard at the British Legation26 His body was later re-interred in the British cemetery located somewhere near the current Beijing Hotel. Burial records for this cemetery were lost during the Chinese Cultural Revolution in 1968.

Lofts wrote of Steel:

“The surgeon was a distinguished doctor from Macquarie Street, remarkable for his efficiency, gentleness, courtesy and culture.

He was a very pleasant companion with a high ideal of what an officer should be. Unfortunately, he died from an overdose of some drug, self-administered. A day or two before he died he remarked to me that if anything happened to him his daughter in Switzerland would hear the news in the papers but if anything happened to her he would not know till long afterwards”.

The report from ‘our correspondent’ in the Sydney Morning Herald wrote:

“He was very scholarly and refined and had an excellent knowledge of German and French, which had been put to practical account many times in China.

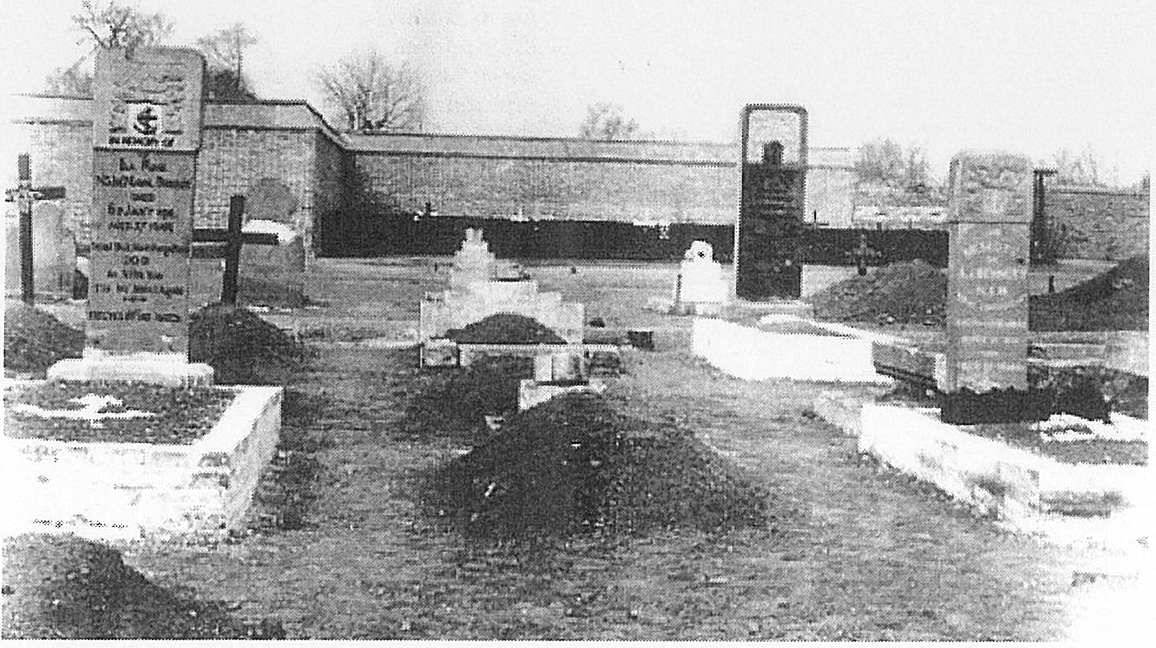

British Cemetery, Peking. Graves of AB’s Rose and Bennett in front. Steel’s is the dark headstone at the rear. (Courtesy Bob Nicholls)

He was highly esteemed and popular. His conversational abilities were much envied. Only two days before his death he had, his brother officers will now remember, made a striking and courageous defence (at) the dinner table of the much-abused missionaries and their work in China. In military circles generally missionary effort is regarded as wasted and the cause of much of the present troubles; but Dr Steel combated the arguments single-handed and won the admiration of those opposed to tom by his able and sturdy plea in favour of missionaries.”

Perhaps one could expect no less from the son of a clergyman. Steel’s obituary in The Australasian Medical Gazette stated:

After Steel’s death at least two requests were made to secure a pension for his daughter. Details on one has not survived but a J. Rutherford wrote from Bathurst on 17 November to the Colonial Secretary the Han John See MLA:

I have an appeal to make, that a pension be granted to the daughter of the later Dr John Steel, who was surgeon to the Naval Contingent from New South Wales in China.

Previous to that he was Staff surgeon to the Naval Brigade and did special service in training the Ambulance Corps.

I append a slip from the Daily Telegraph, which goes to show that he was most indefatigable and energetic with the discharge of his duty to his men and to his country.

He is dead and the means for the support of his daughter and for her education is entirely cut off while the whole family of Steels cannot raise any sum for her help.

I trust that your interest may be aroused in such a way that you will at once furnish to Miss Ruby Steel the means to go on where she is (in Europe) with her education, which I hope will enable he to, in some part, support herself.”28

Apart from a request for a report on this matter the outcome of this heart-rending plea is unknown.

Lofts wrote of the revised medical arrangements for the NSW Contingent:

These medical duties included a medical inspection to weed out those thoughts unable to withstand the winter weather, resulting in three able seamen being dispatched to Tsientin thence Sydney via SS Changsha. The last convoy to reach Peking before the river iced over having arrived on 21 November, the check did not prevent the death of AB Eli Rose of Newcastle from pleurisy on 6 January. On 12 December 10 men were in hospital, including AB Walsh with smallpox despite the shipboard vaccinations.29 On 31 December, 14 men were hospitalised, none serious. At least two men sent for admission to Wei-Hai-Wei had ended up in the Yokohama Hospital in Japan.

Meanwhile, having received their Canadian winter clothing, the Victorians also settled into their Tsientin go down while engaging in police work and municipal chores. Their runs were moved to Peking and it seems there was lots of ‘make work’ overwinter until their departure. Like the NSW contingent, despite almost nonexistent recreation facilities they received praise for their clean and comfortable quarters. Disciplinary problems among the Australians were few and the British Minister at Peking Sir E.W. Satow remarked that there had not been a single complaint against any in the NSW Contingent and that the Victorian Contingent had a similarly high reputation. This contrasted with serious disciplinary breakdowns among the other contingents in Tsientin, where a French mutiny was put down by other troops with several wounded. The Victorians, in particular, had many scrapes with foreign troops (especially the French who drew bayonets with little provocation), sustaining several wounded, none serious apart from AB J. Harding who was left for dead after sustaining sword and sabre wounds in an altercation with some Germans.

Returning Home

The Victorians were able to go sightseeing in Peking from 22 January 1901 and after a quiet February, both contingents were relieved by the Royal Welsh Fusiliers on 23 March. By then the rivers had become navigable again and peace talks had begun. Reporter John Wallace of the Herald wrote in mid-February that the health of the contingents was excellent, with no one in hospital after Walsh had been discharged following his smallpox.

However, the prospect of going home proved too much for AB Arthur Bennett, who was found dead from a gunshot wound on 14 March, leaving a widow and several children. His apparent suicide was possibly the result of being disrated from Petty Offer 2nd class, after assaulting CPO J.G. Sparkes while drunk.

The Victorians departed Tsientin on 25 March and boarded the transport Chingtu (2300 tons) next day. The NSW Contingent was delayed by weather until 29 March, with one man missing the ship and two left behind due to illness (one with rubella and AB Armsby of the Ambulance Party with ‘enteric/brain fever’),32 although all three made it home later. Another 17 NSW personnel accepted job offers from the local railway company.

Chingtu left Hong Kong 5 April and a week later Cpl T.C. Symonds NSWMLI was isolated after Stewart diagnosed ‘chickenpox’. When Chingtu arrived in Sydney on 25 April the quarantine medical officer confirmed it was actually smallpox. Although Symonds was almost convalescent, this significantly disrupted plans for a civic reception. The ship was quarantined pending checks of the vaccinations given the previous August. Following some political pressure 140 men were finally landed on 3 May, but another 80 (including AB’s Hidden, Sale, Gascoine, Sippe, and Field of the Ambulance Party)34 were quarantined for another 14 days. While there Pte C.W. Smart NSWMLI died of smallpox.

Lofts wrote:

As may be expected, although the NSW contingent was feted on their return, the Victorians were left on their own until they boarded a train for Melbourne that evening, arriving home on 4 May.

Conclusion

Compared to the Boer War the Boxer deployments have received little attention, probably because the fighting had ended by the time they arrived. Nevertheless, the NSW and Victorian contingents were frequently complimented for maintaining their morale, in circumstances where other forces failed to do so.

Like the South Australians, several medical themes with the shore deployment have remained constant in the last 100 years, including performing pre-deployment medicals end mass at short notice and sustaining the obligatory casualty-just-on-departure (not to mention concurrent medical officer pay stuff-ups!)

However, with six deaths out of 460 men in six months ashore (i.e. 26 deaths per 1000 per annum). The mortality rate of the NSW and Victorian contingents greatly exceeded the 5.4 deaths per 1000 men experienced by the RN in peacetime in 1899 (or 7.2 per 1000 RN personnel the following year associated with the beginning of the Boer War). By comparison, Australia overall lost only 11.7 per 1000 men per annum from illness in South Africa. Figures for the other China contingents are not available for comparison, although evidence suggests the Australian medical experience were by no means unique.

Of the six deaths, two (including Steel) were by misadventure and four by illness. At least one of the latter (Pte Rogers) may have been prevented if his survey board had sent him home from Hong Kong. It is unclear what conclusions can be drawn by Steel’s death, other than confirming the maxim that the doctor who treats himself has a fool for a patient.

It is noteworthy that despite their Ambulance Party the NSW contingent had five of the six deaths, with two coming from the 24man NSWMLI. The contrast with the Victorians, who only had Staff Surgeon Stewart and SBS Patchett, seems somewhat stark. The most likely reason stems from the impression that the NSW Contingent was less efficient than the Victorian. It seems probable that a collection of individual sailors, lacking collective training, augmented by soldiers and lead by amateurs, would not perform as well as a fairly homogenous group of sailors lead by ex-sailor officers. This is supported not only by the somewhat haphazard recruitment of the NSW Contingent, but by how they were employed in China. It, therefore, seems likely that the Victorians were able to maintain better hygiene standards. Their illness rates (six men invalided home compared with 17 from NSW)3 suggest they even managed to maintain these standards during the march to Pao-ting fu.

Less important reasons stem from the few conclusions regarding the performance of the medical staff. In the absence of enemy action, it seems likely that the first aid-based medical training of the Ambulance Party was of little use for the prevention or treatment of infectious disease. This remains an ongoing theme, including current operations in East Timor. In addition, although both Stewart and Steel were close contemporaries as civilian MOs. perhaps their different levels of Service experience (17 versus four years) was a factor.

On the other hand, any comparison of sickness rates between China and South Africa may be unfair, as the lack of hygiene and facilities in the former may have created a daunting task for medical personnel whatever their level of expertise. Certainly, the apparent failure of the smallpox vaccinations did little to help matters, resulting in at least three cases and one death.

Despite these shortcomings, by maintaining their morale the NSW and Victorian contingents-maintained parity with the South Australians, who had received high praise from the local RN authorities. In this, the shore contingents, aided by their medical staff, did their part in supporting the eventual establishment of the RAN.