J Serrato, H Hassan, C Forchuk

Background & purpose: The unique experiences of homelessness for Indigenous Veterans are currently understudied. The purpose of this review was to assess the current literature on homelessness among Indigenous Veterans, to identify the gaps in the existing knowledge base and to provide an insight into future research.

Materials & methods: Electronic databases including CINAHL, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Homeless Hub and the Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health were searched for relevant research studies. Search terms included ‘Aboriginal’, ‘Indigenous’, ‘First Nations’, ‘Native’, ‘Métis’, ‘homeless’, ‘homelessness’ and ‘Veterans’. References within articles were also searched. To meet inclusion criteria, articles needed to focus specifically on homeless Indigenous Veterans, and be written in English.

Results: The initial search resulted in 32 research articles. No previous systematic or literature reviews were identified, making this review the first of its kind. One study from the United States (US) met inclusion criteria. This identified study reported that homeless Indigenous Veterans were more likely to use alcohol and spent a greater number of days intoxicated but were less likely to use drugs and experience psychiatric problems compared to white homeless Veterans.

Conclusion: There is currently an inadequate amount of research to draw concrete conclusions, thus further investigation is urgently needed. Only one paper was identified indicating that this is not solely a lack of North American literature, but also a lack of research conducted by the international community. This review encourages greater emphasis on future research for potential policy change and recommends an increase in cultural-specific services.

Keywords: Homelessness, Veterans, Aboriginal, Indigenous, Mental Health, Addiction.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The Homelessness Partnering Strategy, Employment and Social Development Canada supported this research.

Introduction

Homelessness among Veterans has become a significant issue for many Western countries yet there has been a lack of censuses investigating the number of homeless individuals and the demographics of such individuals.1 This is largely due to the challenging nature of enumerating the hidden homeless population with no fixed address, no method of communication and who can migrate nationally as well as locally. There are also differences in defining homelessness based on duration (particularly as housing status can change rapidly) and the type of shelter utilised,1 as well as research methods, such as point-in-time counts and night-time counts lacking in validity and reliability.2 Mobility among Indigenous homeless individuals in Canada has been found to be frequent with over 40% of respondents stating they had moved more than three times in 6 months and 18% reporting returning to their home communities seasonally.3 In Canada, it is estimated there are 2 250 Veterans who use homeless shelters every year exact numbers are currently unknown;4 especially as not all homeless people use shelters. Recent statistics in Canada suggest that Indigenous peoples make up 28% to 34% of the homeless population despite only accounting for 4.3% of the Canadian population with a tendency for higher rates of homelessness in western and northern communities in Canada.5 In a study conducted across four Canadian cities (Calgary, London, Toronto and Victoria), it was found that Indigenous and Métis Veterans made up 9.7% of the homeless Veterans sample.6 Currently there is a lack of research investigating homeless Veterans within Canada but in particular there is a dearth of literature specifically focusing on homeless Indigenous Veterans.

There are unique experiences living in Canada as there is differentiation among various Indigenous groups (First Nations, Inuit, Métis) as well as geographical and housing differences (on-reserve, off-reserve, rural, urban, Northern Territories).3 Given this, it is important to investigate the issue of Veteran Indigenous homelessness from a Canadian perspective. Gaetz et al.note that although the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report of 2015 does not specifically discuss homelessness, the report states that the legacy of residential schools used for cultural assimilation has resulted in Indigenous individuals being disproportionally affected by ineffective child protection services, poorer health outcomes, greater rates of substance misuse and an overrepresentation within the criminal justice system;5 all of which may be potential factors in increasing the likelihood of homelessness occurring. Unfavourable historical occurrences such as residential schooling may play a role in influencing the homeless rates of Indigenous Veterans. Similarly, the ‘Sixties Scoop’, during which Indigenous children were removed from their families’ homes by social workers and adopted by non-Indigenous families, may have influenced homelessness among Indigenous Veterans in Canada. The problematic issues that arose included a lack of social identity, physical abuse and racism (perceived and experienced) within adoptive homes.7 This was supported by Ray and Abdulwasi8 (as cited by Abdulwasi, Evans, & Magalhaes7) who performed a secondary analysis of data obtained from a previous study9 and reported that Indigenous Veterans considered their adoptions as contributing factors towards homelessness with many reporting physical and emotional abuse as children, and a lack of connection and belonging to their culture and biological families.8 Further research is required to investigate the underlying causes of homelessness within this population. Difficulties in studying and analysing homelessness among Indigenous individuals can be due to a number of issues including, but not limited to, the lack of identification of ethnicity across services and agencies, an unwillingness to self-identify as Indigenous for fears of discrimination, a lack of Indigenous-led/Indigenous-specific services (including a lack of dissemination regarding these services), which has been found to lead to sampling and recruitment difficulties, and differences in social policy development between municipal/provincial/ federal and on-Reserve/Indigenous governance which can lead researchers to make errors.10 As such, it makes the task of identifying specific demographics (i.e. Veteran status) within this population even more difficult to ascertain. Further, Kramer et al. highlighted the issue of Veteran identification in the US across Veteran health services, revealing that 32 259 of Indigenous Veterans were enrolled on the Veterans Health Administration database but only 44% of this sample was identified as having Veteran status according to the Indian Health Service National Patient Information Reporting System.11 Although literature from the US exists regarding these particular issues among Veterans, Indigenous participants are often underrepresented; less than 2% of the sample.12,13 Additionally, similar studies that have been conducted in the US report participants that do not identify as white, black or Hispanic are considered ‘other’.14

In Canada, it has been noted that alcoholism and other substance misuse have been cited as key factors in contributing to homelessness among Veterans followed by mental health issues and difficulty in successfully transitioning from the military to civilian life.5,15 To ease this transition from military life to civilian life, Forchuk et al.note that an integrated approach to adopting the housing first model, that is, assisting in the attainment of housing as well as intensive case planning and support to assist with independent living skills and health, as well as harm reduction practices can improve access to addiction and mental health treatments in addition to income support.6 Among Indigenous adults in Eastern Canada, one study revealed that 71% of the sample consumed alcohol and 29% endorsed needing help with alcohol consumption.16 Previous research in the US has reported that alcohol dependency, suicidal behaviour, and mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been found to be more prevalent among Indigenous peoples compared to the general population.16,17 Despite the findings from these latter two studies, there has been extremely limited literature regarding addiction and the psychiatric needs specific to homeless Indigenous Veterans. A survey by the Wilder Research Group of homeless and near-homeless people on Indigenous tribal reservations in Minnesota revealed that 8% of men had served in the military and not only demonstrated higher rates of physical and mental health concerns, but were also twice as likely to consider themselves alcohol or drug dependent compared to non-Veterans.18 Furthermore, in the US, policy conflicts between the 1996 Native American Housing and Self-Determination Act and the Housing Act of 1937 has prevented Indigenous Veterans from using rent vouchers for federally subsidised houses on reservations. As most reservation housing is federally subsidised, this results in homelessness or inadequate housing.19,20

The objective of this review is to provide an overview and assess the literature regarding homeless Indigenous Veterans. It is hoped this will inform policy and interventions and highlight the gaps in current knowledge that need to be addressed by future research. This review aims to examine the issues surrounding homelessness among Indigenous Veterans and places a primary focus on homeless Indigenous Veterans’ unique needs and risk factors that predispose them to, or as a result of, becoming homeless.

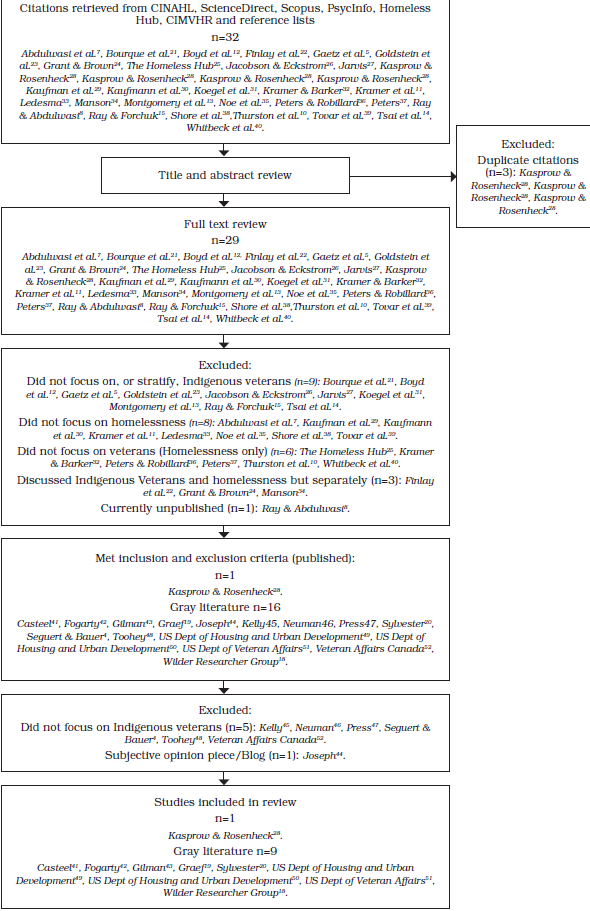

Figure 1. Flow chart of search strategy and study selection

Method

Search strategy

The search strategy for this review of all literature published up until 14 February 2017, utilised five academic databases; CINAHL, The Homeless Hub, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, SCOPUS as well as the official journal of the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Research (CIMVHR), The Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health. Searches were conducted using the terms ‘Homeless or Homelessness’, ‘Veterans’ and ‘Native, Aboriginal, Indigenous, First Nations or Métis’. To supplement the search, additional articles were retrieved by investigating references cited within articles obtained from the database search. Grey literature was also sought through searches on the Veteran Affairs Canada (VAC), US Department of Housing Development (HUD), US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Australian Department of Veterans Affairs and New Zealand Veteran Affairs websites as well as a generic Google search. Identifying grey literature was considered to be important to the search strategy as there was potential for there to be a less-developed body of literature concerning homeless Indigenous Veterans. Two reviewers conducted the database searches, reviewed the database results, arbitrated disagreement and consensus was reached after discussion. Figure 1 outlines the literature selection process. In order to meet the inclusion criteria for this study, peer-reviewed articles had to focus on homeless Indigenous Veterans specifically, be written in English, and not have been included in a prior review as prior systematic and literature reviews were included. Articles that were perceived to be potentially useful or contained a title pertaining to homeless Veterans or Indigenous were initially included. After reading the full text, articles were excluded if they did not focus specifically on homeless Indigenous Veterans, or if they did not stratify the results of homeless Indigenous Veterans from the rest of the study sample. Articles that described homeless Veterans or Indigenous Veterans separately were excluded. Furthermore, no exclusion criteria were set for research design, type of intervention, country of origin, nation served or the age of the sample. Grey literature was included; however, opinion pieces were excluded due to their subjective nature.

Selection of articles and data extraction

Articles found as part of the search strategy we reviewed by title and abstract to assess whether the article was relevant to the purposes of this review. Duplicates were also removed at this stage. The remaining articles were then read in full to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. Grey literature was observed and selected for background context using the same selection approach but was not included in the review. It was planned that identified studies would be categorised into one of the following topic areas: epidemiology, health and services access/utilisation and quality care/effectiveness.

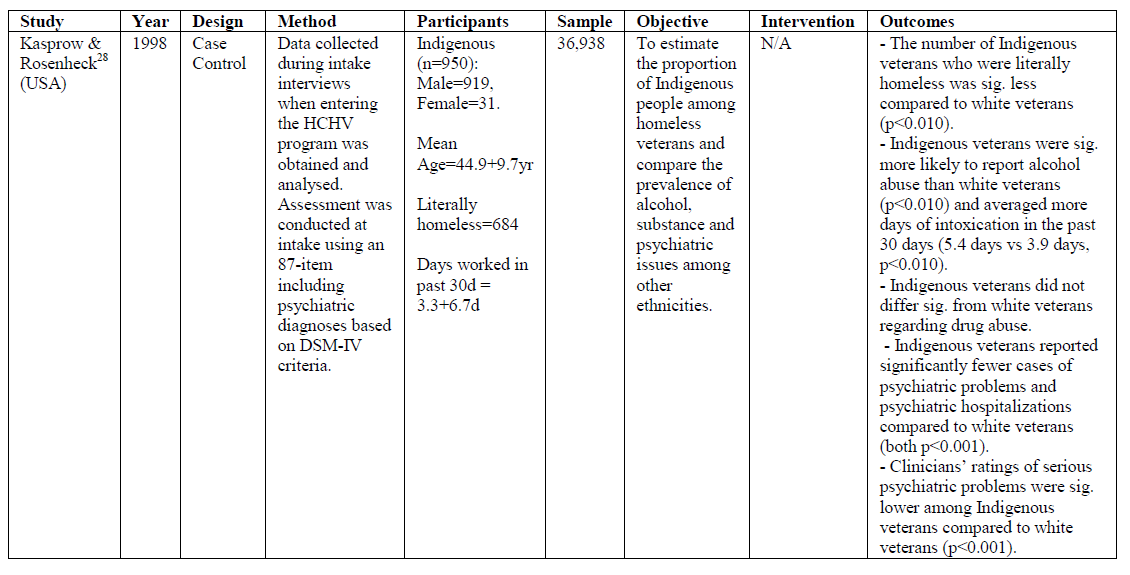

Variables extracted from the identified articles included study design, the objective of the study, participant demographics, sample size, methodology, whether an intervention was provided (and if so, what the intervention was) and the results of the study. An evidence table was created with these variables (see Table 1).For the purpose of this review, an epidemiological study was defined as any study that included estimates of the size of the population and prevalence of homelessness among Indigenous Veterans, characteristics of homeless Indigenous Veterans, factors associated with the likelihood of an Indigenous Veteran to experience homelessness, or other epidemiological information concerning homelessness among Indigenous Veterans.

Results

Search results

Of the databases and reference lists searched, 32 articles were identified. This number reduced to 29 once duplicates had been removed and was further reduced after the full text of the articles had been read and verified. Of the 29, nine articles did not focus on Indigenous Veterans and only focused on homeless Veterans in general, eight did not investigate homelessness but did focus on Indigenous Veterans, six did not focus on Veterans and three explored Indigenous Veterans and homelessness but independently of each other. One article had not been published at the time of the search and therefore the full text could not be accessed. The results of this unpublished study were discussed in a later article by one of the authors7.This resulted in only one epidemiological paper being identified. There were no previous literature review or systematic review papers found, making this review the first of its kind. Sixteen articles were identified in the search for grey literature. Eight were news articles from newspapers or online news outlets, two were press releases from the HUD, one was a report from the VAC concerning future plans for Veteran homelessness, one was a report on homelessness on tribal reservations in Minnesota, USA, one was a grants report from the VA, one was a doctoral dissertation and one was a blog post. Of this literature, six were not specific to Indigenous Veterans and the blog post was excluded due to the subjective nature, thus leaving nine used to supplement this review.

Summary of study

The only study identified for the purposes of this review was conducted by Kasprow and Rosenheck who investigated alcohol and drug misuse among Indigenous Veterans at 71 Veteran Affairs Health Care for Homeless Veterans (VA-HCHV) sites across the US.28 However, the study did not focus on the causal factors for homelessness, instead providing an insight as to the struggles of homeless Veterans. The Indigenous Veterans in the study (n=950) were stratified from the total sample population which included other ethnicities including white, black and Hispanic (n=36 938).From a prevalence perspective, there were significantly fewer Indigenous Veterans who were ‘literally homeless’ compared to white Veterans (p<0.010).However, when a comparison was made between the number of Indigenous Veterans in the VA-HCHV program and the proportion of Native American Veterans in the 1992 National Survey of Veterans, it was revealed that there were approximately 19% more Indigenous Veterans reporting homelessness than expected. The difference between these two estimates of homelessness reached statistical significance (p=0.044).This would suggest that there is an overrepresentation of Indigenous Veterans experiencing homelessness.

Experiences of homeless Indigenous Veterans compared with the non-Indigenous homeless Veteran population

Kasprow and Rosenheck reported that Indigenous Veterans were notably more likely to consume alcohol and averaged a significantly greater number of days under the influence of alcohol in the past 30 days (both p<0.010).28 This finding was further supported by clinician ratings of alcohol dependency with Indigenous homeless Veterans demonstrating a higher odds ratio (OR=1.46) when compared with white Veterans. Overall, Indigenous Veterans’ scores on all alcohol misuse and dependency measures were approximately 40% greater than white homeless Veterans.

However, it was also reported that Indigenous Veterans were less likely than white Veterans to report drug misuse and there was no significant difference between Indigenous and white homeless Veterans in regards to the number of days of drug misuse. In addition, Indigenous Veterans demonstrated the lowest rates of hospitalisations due to drug dependency compared to all other ethnic groups. Homeless Indigenous Veterans reported significantly fewer cases of psychiatric problems and psychiatric hospitalisations than white homeless Veterans (both p<0.001).Furthermore, clinician ratings of psychiatric problems verified the latter findings as the ratings suggested serious psychiatric problems were lower for Indigenous Veterans compared to white Veterans (also p<0.001).However, it should be noted that this does not imply that Indigenous Veterans demonstrated low rates of psychiatric issues. All of the homeless Veterans in the study reported high levels of psychiatric problems but the results reveal that significant differences between ethnic groups were observed.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to review the literature concerning homeless Indigenous Veterans. Of concern, only one paper was identified that had been conducted in 1998 within the US. This is an alarming amount of time to pass with little to no research conducted on this specific population. Of course, this is not to suggest that no research has been conducted at all as our search demonstrated a number of studies assessing Indigenous Veterans and homeless Veterans separately, but there is a lack of evidence investigating homeless Indigenous Veterans. There was one paper identified in the search that focused specifically on homeless Indigenous Veterans in Canada, but this article is an unpublished thesis8 that had been referenced in another article.7

The prevalence of homelessness among Indigenous Veterans in the US was found to be higher than expected by Kasprow and Rosenheck28.However, the authors go on to note that the national survey (used for comparisons with the study sample) included Veterans from both urban and rural areas whereas the HCHV sample was predominantly from urban areas, thus indicating that if geographical differences were accounted for, the difference in the proportion of homeless Indigenous Veterans may have been higher. The second major finding from Kasprow and Rosenheck28 was the higher prevalence of alcohol misuse among Indigenous homeless Veterans relative to white homeless Veterans. However, the study did not assess the nature of the alcohol misuse (i.e. binge drinking or frequent consumption of smaller quantities). The authors suggest that further research into the behavioural aspect of alcohol misuse among homeless Indigenous Veterans is needed to provide greater clarity. One potential issue with the data was the reliance on face validity as standardised assessment scales were not used although the authors argue that due to the large sample, biases may have been reduced as they would had to have been applied consistently over such a large number of Veterans and clinicians. Kasprow and Rosenheck28 recommend that preventative treatment services should aim to target homeless Indigenous Veterans and that further research assessing the appropriateness and effectiveness of services available are culturally specific. As this study was conducted almost 21 years ago in the US, it re-emphasises the need for a new study, particularly in Canada.

Further to the issue of health-compromising behaviours such as alcohol and substance misuse, mental health issues such as PTSD, depression and anxiety have also been found to be prevalent. Co-occurring disorders that include at least one alcohol/drug use disorder and at least one non-drug related mental disorder was reported among 37% of homeless Veterans sample.53 In particular, PTSD was also found to be more prevalent among Indigenous Veterans compared to non-Indigenous Veterans.22,24 A recent literature review revealed that homeless Veterans were significantly more likely to report a chronic health condition compared to homeless non-Veterans and more likely to have a hepatic disease, HIV/AIDS and a psychiatric disorder when compared to non-homeless Veterans.54 Homeless Veterans in the US were also found to have a higher rate of diabetes compared to previously published data on the general homeless population (19% vs 8%).55 Furthermore, it has been found that Veterans experiencing homelessness for the first time were significantly associated with heart disease, hypertension and joint pain disorder.56

Table 1. Overview of Identified Literature

A literature review written in the US by Tovar, Patterson Silver Wolf and Stevenson suggests that community rituals and ceremonies can help bring a sense of belonging for Veterans by reaffirming tribal identity and to absorb any trauma the Veterans have experienced.39 Culturally-informed rehabilitation has also begun to rise with the VA in the US providing transportation for Indigenous Veterans attending VA facilities and the opening of a tribal VA clinic.39 This represents a shift in healthcare by providing for a specific population that requires greater assistance. In addition, Kaufmann, Buck, Floyd and Shore reported that the VA has implemented a community outreach program designed to engage Indigenous Veterans in the US with VA information and assist with paperwork as well as encouraging Veterans to seek help through the VA’s American Indian Telemental Health Clinics.30 The program has since expanded across the US, including remote areas of Alaska. Although these studies represent promising signs of improvement for Indigenous Veterans’ healthcare, there still appears to be a lack of additional services specifically aimed at homeless Veterans. Cultural-specific services and treatment may be recommendable as a recent study in the US reported that being an Indigenous Veteran was associated with lower odds of treatment entry compared to white Veterans.22 The interventions described by Tovar et al.39 and Kaufmann et al.30 have been implemented in the US, but not in Canada.

Despite the lack of research, the grey literature identified in this review revealed that homeless Indigenous Veterans are receiving more recognition and that further assistance is being provided. The VAC have reported that homelessness and the transition from the military to civilian life will be addressed with a series of planned initiatives starting in 2015 and 2016 through to 2019 and 2020 including improved identification of homeless Veterans, new employment strategies and greater mental health support for Veterans and their families.52 Although a much-needed and welcomed sign of progress, there was no further detail as to how Indigenous service providers and Veterans would be supported specifically. Given the issues highlighted by Thurston et al.10 earlier in this review, it is conceivable that these issues could also be applicable to Indigenous Veterans. It would also appear that action is being taken in the US as $5.9 million in grants from the HUD and the VA has been awarded to 26 tribes to provide permanent housing and support services to homeless Veterans including rental assistance vouchers,41,43,50 as well as an expansion of the HUD-VA Supportive Housing program to Veterans living on tribal lands.42,49 Overcoming the legislative barriers in place, as outlined by Graeff19 and Sylvester,20 is a promising step in providing greater support for Indigenous homeless Veterans in need.

As this review has demonstrated, there is a great need for further Canadian research. The key limitation for this review is the fact that no Canadian research articles were identified for analysis. Future research needs to explore the cultural-specific causes of homelessness among Indigenous Veterans in order to fill the gaps in the current knowledge. In doing so, post-discharge services can better equip Indigenous Veterans upon transitioning into civilian life and address the risk factors for homelessness. Further, as Kasprow and Rosenheck28 revealed, the consequences linked with being a homeless Indigenous Veteran also require greater attention such as the health-compromising behaviours associated such as alcoholism, drug use and psychiatric disorders. As the article was conducted in the US 21 years ago, a modern analysis within a Canadian context is certainly warranted. However, it is clear that this is not just an issue specific to Canada, but for other Indigenous populations across the Western world as international literature was also found to be lacking. This suggests that ethnographic research would be essential in identifying the cultural differences of homeless Indigenous Veterans in their transition to civilian life. Ethnographic research would also allow a greater understanding of the challenges faced by Indigenous Veterans and of what more can be done in targeting this specific group of the homeless population. There is also a need for an Indigenous-led community-based study to provide further context in order to enhance the current knowledge of homeless Indigenous Veterans. Qualitative research studies are needed to understand further the unique experiences of Indigenous Veterans and their perspectives on homelessness. Not only would this allow for a rich source of data directly acquired from Indigenous Veterans, it may also be possible to further inform future interventions, services and policy in the prevention and support of homelessness for this distinct group within the homeless population. With further investigation could highlight the social, health and psychological issues, could provide greater emphasis and inspiration for future studies internationally.

Conclusion

The present state of the literature is alarmingly inadequate in assessing the prevalence and needs of homeless Indigenous Veterans.

There seems to be a greater volume of attention towards homeless Indigenous Veterans in the US.

The only study identified in the search was conducted in the US and suggested that homeless Indigenous Veterans are at great risk of homelessness and alcoholism compared to white homeless Veterans but may demonstrate fewer psychiatric concerns and lower rates of drug dependency.

Further research is required to assess the current trends in homelessness among Indigenous Veterans and greater attention from policymakers in working with this population.

Corresponding Author: Jonathan Serrato, jonathan.serrato@lhsc.on.ca Authors: J Serrato 1, H Hassan 1, C Forchuk 1,2

Author Affiliations:

1 Parkwood Institute, MHNRA

2 Western University Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing