Abstract

The present study was part of an evaluation of the Arts for Recovery, Resilience, Teamwork and Skills (ARRTS) program conducted by the Australian Defence Force (ADF) for wounded, injured and ill veterans as an adjunct to their established treatments. Two previous evaluations, one using categorical judgments and one using standardised rating scales, yielded evidence of overall benefit plus specific benefits in terms of behavioural activation (e.g., sense of purpose and achievement), belonging (sense of social contact and inclusion), sense of flow (concentrated engagement) and good relationships with instructors/mentors. The previous evaluations diverged in their evidence regarding the duration of the benefits of the ARRTS program. The first indicated that high levels of benefit lasted over 24 months, but the second study revealed that the ratings returned to baseline within six months. The current evaluation used primarily categorical judgments of benefits, focusing on the three- and six-month intervals following the program. In agreement with the first evaluation, benefits remained at high levels through the three- and six-month periods. In addition to the categorical judgments, most respondents reported continuing with art-based activities following the program, plus a desire for follow- up contact with fellow participants and arts groups. The results of this and previous evaluations are discussed with respect to emotional memory processes that encode the overall reaction but not its detailed aspects over time.

Introduction

Art-based activities have been beneficial adjuncts in the remediation of disorders including anxiety, depression and PTSD.1-3 Art-based activities have also been associated with improved socialisation, resilience, sense of belonging and quality of life.4-6 To test the value of arts-based activities (visual, written and musical) for wounded, injured and ill veterans, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) conducts Arts for Recovery, Resilience, Teamwork and Skills (ARRTS) program for one month on a biennial basis. The present study was the third in a series of evaluations aimed to identify any beneficial effects of the program as experienced by the participants.

The first evaluation in this series was a retrospective study, comprising 31 of 119 participants contacted 18 to 42 months after completing the ARRTS program through 2015 to mid-2017.7 The respondents replied to 16 statements concerning their experiences, e.g. ‘I had a sense of achievement from the activities I undertook.’ Four statements applied to each of four categories, namely, experience of behavioural activation (sense of purpose and achievement), belonging (sense of social contact and inclusion), sense of flow (concentrated engagement in activity) and instructor relationship (relationship with instructors/mentors.) For each statement, the respondents were asked to tick a box as to whether the statement applied to themselves before, during and/or after the program. Across all four categories, 23% of the respondents recalled having the experience before the program, rising to 87% during the program and declining to 61% after the program. In response to a further question about the duration of the benefits, 15% recalled the benefits only occurred during the program, while 61% recalled that the benefits were enduring, lasting up to 24 months or longer.

The second, previous evaluation provided a detailed examination asking whether or not there were ongoing benefits at three- and six-month follow- up periods. The respondents (N = 92) represented 86% of participants from programs between late 2017 and late 2019. Rather than broad categorical questions, the second evaluation used standardised rating scales corresponding to the four categories of mechanism examined in the first evaluation. For behavioural activation, belonging, sense of flow, and instructor relationship, a detailed description of each measure may be found in Watt and Kehoe.8 Unlike the enduring recall of past benefits observed in the first evaluation, the ongoing benefits largely disappeared within six months.

In both evaluations, respondents reported a positive effect of the ARRTS program. However, the two evaluations yielded different estimates of the ongoing benefit, specifically 24 months or more in the first evaluation versus six months or less in the second evaluation. This difference in outcome may be attributable to differences in the measurement instruments, specifically, categorical measures of presence/absence versus multi-point ratings on standardised scales. To help resolve this apparent divergence, the present evaluation included presence/absence measures that were aligned with the content of the rating scales used in the second evaluation. Moreover, questions were added to obtain a behavioural indication of whether the activities in the ARRTS program endured after its conclusion and whether the respondents wished to have further engagement with the program.

Table 1. Respondent demographics

| Gender | |

| Male | 23 |

| Female | 14 |

| Age | |

| <30 | 10 |

| 3039 | 12 |

| 4049 | 9 |

| >50 | 6 |

| Rank | |

| Officer | 10 |

| Senior Non-Commissioned Officer | 5 |

| Other Rank | 18 |

| Civilian | 4 |

| Service | |

| Navy | 12 |

| Army | 15 |

| Air Force | 6 |

| Civilian | 4 |

| Creative Stream | |

| Visual Arts | 19 |

| Creative Writing | 7 |

| Music and Rhythm | 11 |

Method

Respondents. The respondents (N=37) for the current research participated in the two cohorts of the 2019 ARRTS program and represented 85% of participants. Respondent demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 2. Benefit, activity and situational questions

-

- Upon reflection, was the program beneficial? (Yes/No)

- If beneficial, how did the art activity provide benefit? (Tick all that apply to you:)

- Flow (being in the moment, losing track of time)

- Purpose*

- Meaning*

- Achievement*

- Enjoyment*

- Did the program provide a: (Tick all that apply to you:)

- Sense of Belonging

- Positive interaction with staff

- Have you continued with an artistic endeavour? (Tick all that apply to you:)

- Writing

- Music

- Theatre

- Visual Art

- Other

- Have you found another activity since completing the program this is providing benefit?

e.g., sport, yoga, other: - As a result of the program, is the positive effect your participation ongoing?

(Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree) - If follow up was provided would you have liked: (Tick all that apply to you:)

- A phone call

- A catch up with the participants of my program

- A catch up with the participants of all programs

- Another activity that encouraged belonging

- Another activity that encouraged purpose

- Another activity that encouraged achievement

- Another activity that encouraged flow (being in the moment or the “zone”)

- Finding a similar art group in my local region

Procedure and materials. For the participants who consented, a link to the Qualtrics online platform was sent at three months and six months following the program. There were 34 and 29 completed replies, respectively. The questions asked of the respondents are contained in Table 2. The current evaluation was approved by the Departments of Defence and Veterans Affairs Human Research Ethics Committee, Protocol 853-17.

Results

Benefit of the program. At three months, 94% of respondents considered participation to have been beneficial, as did 86% of respondents at the six- month period (Question 1). The apparent decline was not statistically significant; the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the two percentages crossed the zero-difference point. While some respondents did not answer the question, no respondent indicated that the program was a negative experience. With regard to the possible contributing mechanisms (Questions 2 and 3), the majority of respondents at both the three- and six-month periods (with one exception) indicated the benefits of the program included flow (62%, 66%), purpose (56%, 52%), meaning (56%, 55%), achievement (71%, 48%), enjoyment (79%, 76%), sense of belonging (88%, 93%) and positive interaction with staff (82%, 76%). Any apparent differences in specific benefits and/or changes over time were not statistically significant based on zero crossings of confidence intervals.

Sustained benefit of the program. When asked whether the positive effect of participation was ongoing (Question 6), 85% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed that the benefits continued over the three- month and six-month periods. In addition to the ongoing benefit, the preponderance of respondents had continued with art-based activities over both time periods (94%, 97%) (Question 4). Beyond the art-based activities the program provided, 59% of the respondents indicated taking up other art- based and/or physical activities in the three months following the program, which decreased, although not significantly, to 48% after six months (Question 5). The selected activities at both time points were variable, including, among others, swimming, mountain biking, yoga, astronomy, woodworking and knitting,

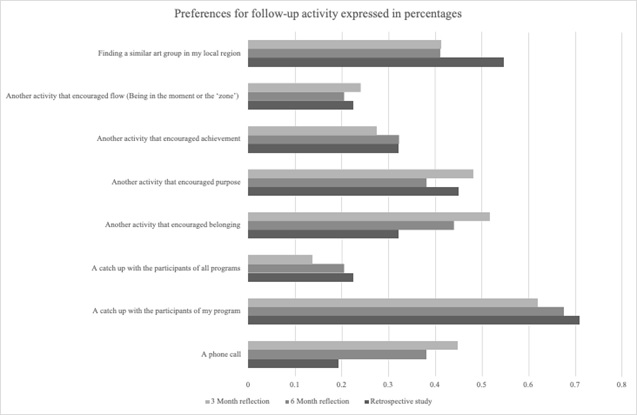

Sustained engagement. Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents who reported what kinds of sustained engagement they would desire after the program’s conclusion at both the measurement points (Question 7). In addition, the corresponding percentages obtained from the previously described first evaluation are also depicted.7 Among the options, ‘A catch up with the participants of my program’ was selected most frequently in both this and the first evaluation (62% or greater). In contrast, ‘A catch up with the participants of all programs’. was selected least often (23% or less). The difference in confidence interval did not cross the zero point. Less than half the respondents typically selected the other listed activities in either the present or first evaluation.

Figure 1

Discussion

Benefit of program

When asked to reflect on their participation in the ARRTS program, the vast majority of respondents recalled a benefit from the program up to six months later. In particular, a majority typically recalled a benefit related to their flow states, purpose, meaning, achievement, enjoyment, sense of belonging and positive interaction with staff during the program. When asked whether the positive effects of the program were ongoing, 85% of respondents reported that positive effects were sustained across six months.

The present results largely confirm previous findings that respondents experienced benefits from the ARRTS program. In the present study, the respondents experienced both an overall benefit plus specific benefits based on their reflections on the four mechanisms, all of which continued over the six-month follow-up period. Similarly, the first evaluation found overall benefit and specific benefits related to the four mechanisms. In contrast, in the second evaluation, the standardised, multi- item questionnaires used more precisely defined measures of experienced benefits. In that case, the particularised benefits diminished substantially within six months.

The difference in the duration of the experienced benefits may be attributed to memory encoding mechanisms for emotional events. Recall of even highly salient events such as physical injury can change substantially over the time intervening between initial treatment and recovery.9 More generally, over retention intervals, the central aspects of an event, including major emotional reactions, can be readily retrieved while details are lost.10 In terms of the three evaluations, retrieval of the overall and specific mechanism-related benefits appeared to remain retrievable over several months and years, while precisely defined measures are less retrievable.

Behavioural change and engagement

Beyond subjective benefits, respondents in the present study also reported objective behaviour change. The respondents indicated that nearly all (97%) continued with art-based activities offered during the program at the end of the six-month follow-up. In addition, at the end of the follow-up, nearly half (48%) of respondents had undertaken a wide variety of behaviour-based activities. In addition to self-initiated activities, many respondents (96%) indicated a desire to both sustain connections with their cohort in the ARRTS program and developed connections with other relevant groups.

Limitations and future directions

The present study indicated that the substantial perceived benefits of the ARRTS program persisted for at least six months. However, both this study and the similar persistence seen in the first evaluation7 were based modest sample sizes (Ns < 38). Thus, they had limited power to detect any downward trend as was seen in the second evaluation, which had a larger sample size (N=92). Thus, future research with greater numbers would provide the power to detect trends over time in both categorical measures of benefit versus standardised scale ratings.

Conclusion

The current study extended the existing knowledge on how to engage military personnel with art-based activities as an adjunct to their previous and ongoing clinical treatment. Based on the respondents’ recall, the ARRTS program provided both overall and specific benefits. Additionally, the results indicated that participants continued with arts-based activities, and they desired follow-up activities.

Corresponding author: Tavis Watt, tavis.watt@unsw.edu.au

Authors: T Watt1,2, E J Kehoe1

Author Affiliations:

1University of New South Wales – School of Psychology

2 Australian Army