Abstract:

Although dengue became endemic in northern Australia in the 19th century, the enormous movement of people and material during World War II resulted in localised dengue epidemics in Queensland. Factors promoting the epidemics included mixing diverse civilian and military populations, including evacuees from tropical areas, and little focus on preventive measures until outbreaks occurred. Epidemics consisting of a few thousand recognised dengue cases were seen in both Townsville and Brisbane. Brisbane hospital records showed 116 cases in 1942 and 87 cases in 1943. US units experienced attack rates of 80% over a few months. All dengue outbreaks in Australia since 1980 have been due to the introduction of the virus by viraemic travellers. The threat of re-introduction will continue.

Dengue rate in US soldiers in Northern Territory and Queensland 1942

Approximately 80% of all US personnel in this area were attacked within a period of about 3 months.1

Dengue is an arboviral infection spread by Aedes mosquitoes, which can spread rapidly through unprotected military units. The Southwest Pacific Theatre of World War II was marked by dengue epidemics in deployed forces, which had operational consequences, primarily due to the large number of casualties and the frequent occurrence of post-viral fatigue syndromes. Many Australian and US soldiers were infected with dengue in Australia during the military build up to the various offensives in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.1,2 Although dengue exists in Australia today, it is largely the consequence of focal spread from individual travellers to Australia from tropical locations.3 Large dengue epidemics in modern Australia would likely depend on extraordinary collections of mixed military and civilian populations under field conditions, which likely explained the wartime dengue epidemics in Queensland.

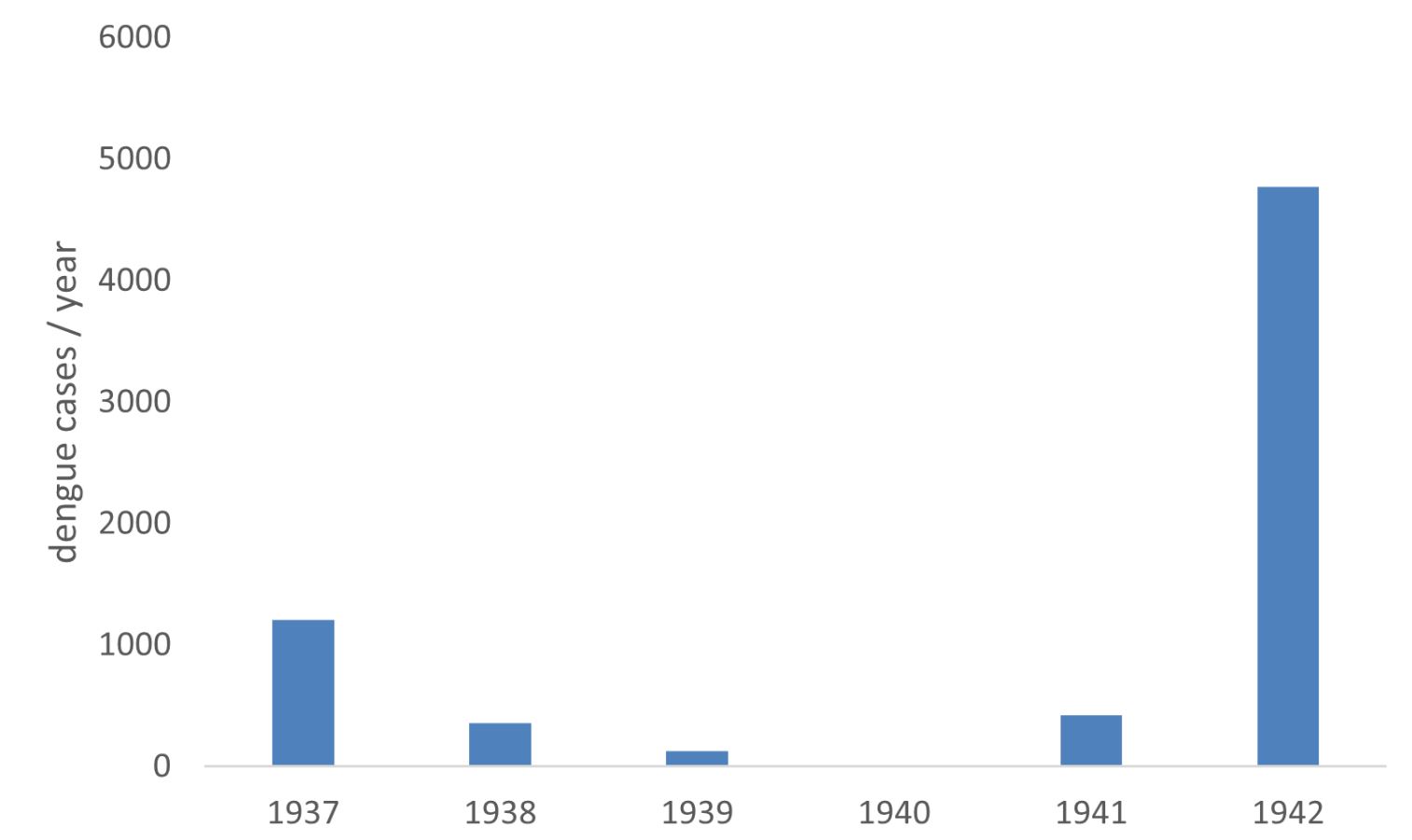

Dengue was endemic in northern Australia from the late 19th century, with large outbreaks occurring in 1897 and 1905.4,5 It was the view of Queensland Health authorities that dengue was endemic in the Northern Territory and only reached Queensland through travellers2,6 Dengue was included with malaria as a vector-borne disease whose control in Queensland largely depended on excluding cases by quarantine procedures.7 During the massive movement of both military and civilian populations during the general mobilisation to face the expected Japanese offensive, this epidemiologically questionable approach was never going to be effective. Beginning in early 1942, large numbers of Australian and US military personnel arrived in Queensland, and civilians were evacuated from islands in the Torres Strait. Dengue epidemics began in the Northern Territory around Darwin and were soon reflected in disease in Townsville from 1941 and Brisbane from 1942.2,7 The Townsville epidemic was thought to have occurred from spread via Cloncurry, Longreach and Charters Towers.2 This may have reflected a major transport route from the Northern Territory to Queensland (see Figure 1 showing several thousand dengue cases in Townsville in 1942, where peak incidence was estimated at 25/1000 men/week).2 Figures for Brisbane are less reliable because dengue was not a reportable disease until January 1943. Brisbane hospitals recorded 116 inpatients in 1942 and 87 in 1943.8 Outpatient cases were under-reported with some medical practitioners claiming they did not have time to report cases and that as few as 20% of cases were being recorded. However, 599 cases, with numbers peaking in March 1943, were noted in various Brisbane newspapers.9

Figure 1: Dengue cases reported to the public health authorities in Townsville, Queensland 1937–42.8

Dengue’s military significance during World War II became all too apparent when > 8000 cases occurred in the Australian Imperial Forces (7th and 9th Divisions) during operations in New Guinea in 1943.7 Dengue’s effect was particularly noted during the Morobe, Lae, Finschhafen, Markham and Ramu Valley campaigns. The lack of specific symptomatology or a diagnostic test meant that most of these cases were ‘pyrexia of unknown origin’ determined as an epidemic. The first isolates of dengue virus, which would enable the development of diagnostic tests and research to develop a dengue vaccine, were made by Susumu Hotta in Japan in 1943.10 Later, and independently, LTCOL Albert Sabin of the US Army isolated dengue viruses from troops in New Guinea, including Australians.11 The most important differential diagnosis was partially suppressed malaria, which was extremely common in the same soldiers in New Guinea who were often on less than perfect atabrine (mepacrine) chemoprophylaxis. Although no cases of dengue haemorrhagic fever were described, the cost to military operations was in large numbers of front-line soldiers who were physically unable to fight often for a few weeks due to dengue fever and its aftermath, characterised by post-viral fatigue.12,13

US Army forces also were severely affected by dengue. In March and April 1942, an extensive dengue outbreak occurred in two US Army infantry divisions (32nd and 41st), concentrating in Queensland and the Northern Territory before moving to Papua New Guinea. In 3 months, > 80% were estimated to have become ill with dengue. Further dengue epidemics were reported in early 1943 in Rockhampton (463 cases) and Brisbane.1 Preventive medicine teams in Rockhampton sprayed waste oil on standing water to prevent breeding of the Aedes aegypti vector; however, mosquitoes were still breeding in 80% of 6000 houses surveyed (see Figure 2). Dengue continued to be a major military medical problem in the Southwest Pacific Theatre, with > 24 000 dengue cases reported by the US Army in New Guinea during 1944.1 Whether the infection originated from the earlier Australian epidemics or was indigenous to New Guinea was an academic question of little practical importance.

Figure 2: US Army photo of preventive medicine soldiers spraying kerosene on water to kill mosquitoes near Rockhampton 1942. Copyright now in the public domain.1

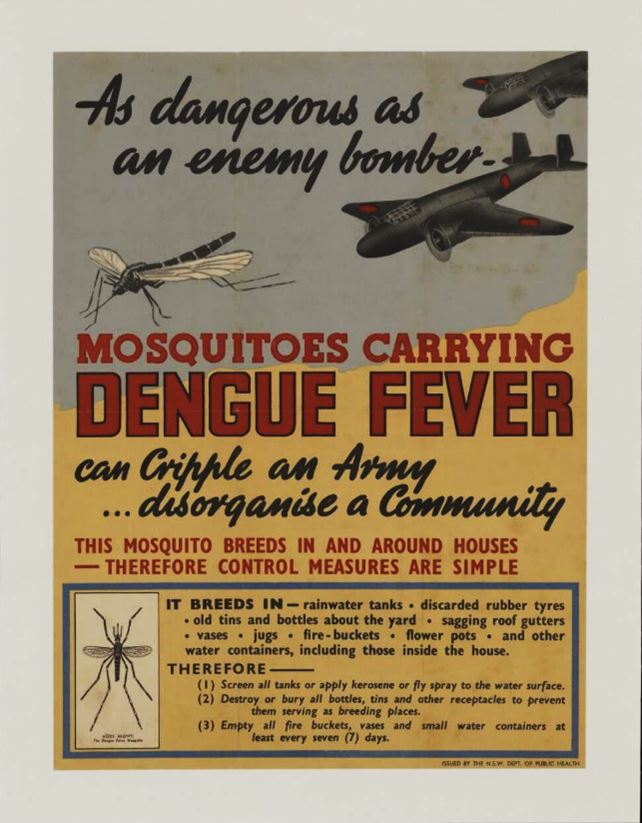

Dengue was considered an important threat to the health of civilian populations in Queensland and, by extension, to the vital logistical efforts to support soldiers fighting in New Guinea. In 1942, a review article (without any direct casualty figures because these were restricted during wartime) was published in the Medical Journal of Australia to inform medical officers and physicians throughout Australia because dengue had spread to northern New South Wales.14 Convincing civilian populations that mosquitoes were as dangerous as an enemy bomber and that one’s familiar rainwater storage tanks were an important source of mosquito breeding was unlikely to be successful, but attempts were made to educate the civilian population as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Poster proclaiming the danger (as an enemy bomber) of dengue infection to the Australian war effort during World War II. NSW Department of Health.

The root cause of dengue epidemics in Queensland during World War II was the massive mixing of human populations during war mobilisation in an area where the principal vector, Aedes aegypti, was abundant and had first been shown to be a vector of dengue virus. Given the historical circumstances, it is hard to see how it could have been otherwise. The mosquitoes were well entrenched in the environment, and most control measures were unlikely to have impacted much, especially after epidemics had already begun. Although dengue vaccines have been progressing towards registration for 70 years, a vaccine of use to the military may soon be on the horizon.15 It is unclear what level of protection a vaccine will provide in personnel operating in an unimmunised civilian population. In thinking about future regional military contingencies, it is worth remembering that more dengue cases than malaria occurred in the ADF while deployed to East Timor.16 Dengue remains a threat to Australian and Allied troops garrisoned in northern Australia or deployed in most tropical regions of the world. Military personnel must understand that repellents and insecticide-impregnated uniforms provide some personal protection against dengue, and broader public health measures are required for formations.

Corresponding Author: G Dennis Shanks, Dennis.Shanks@defence.gov.au

Authors: G D Shanks1,2, J Aaskov3

Author Affiliations:

1 ADF Malaria and Infectious Disease Institute

2 University of Queensland – School of Public Health

3 Queensland University of Technology