C Deans

Abstract

Background: Veteran services increasingly use peers to support other veterans. There are hypothesised

benefits for the service users, service system and peers.

Purpose: This rapid narrative literature review sought recommendations for the employment of veteran peers

via related reviews: one on the use of mental health peers, and one on the use of veteran peers irrespective of

setting.

Method: Searches were conducted using PsycINFO and PubMED databases for peer-reviewed articles over the

past decade.

Results: Part A of the search returned 117 articles. Article categories were: case studies, single program evaluations, descriptive pieces, literature reviews and employment. There were no outcome evaluations with control or comparison groups. Part B of the search returned 20 articles. Article categories were: case studies, peer, consumer and employment experiences. There were no pre-post program evaluations.

Conclusion: There is limited evidence for the benefits of mental health peers or veteran peers. From the current literature, some anticipated benefits and recommendations for the employment of veteran peers can be derived. Anticipated benefits include engagement with providers, social support, stigma reduction, client engagement, program completions and peer benefits. Considerations for employment include principles, selection, training, staff roles, organisational considerations, consumer access and peer care.

Key words: veteran, mental health, peer, employment, benefits, care

Introduction

A peer (‘peer’, also known as a ‘lived-experience peer’, ‘peer supporter’, ‘peer-support worker’, ‘wellbeing responder’, etc.) can be described as a person with a lived experience of adverse events, who offers support and/or services to other people with similar circumstances considered to be less progressed in their life journey.

The use of a peer model emerged within the addiction recovery and mental health settings. There are hypothesised benefits for the service users, mental health service systems and peers themselves.

Within the veteran space, peers have been used for a variety of reason. For example, the United States Veterans Affairs have experimented with peer mentors for homeless or incarcerated veterans. There has also been some use of peers for physical health conditions, such as recovery from cardiovascular disease.

However, the most effective use of veteran peers has been in the mental health field in assisting veterans with mental health difficulties in accessing and participating in care. However, there appears a paucity of research studies to guide organisations serving veterans as to what benefits an organisation can gain from the use of peers. There is also little guidance on the process of selecting and employing peers, how they might be trained and utilised, how to reduce risk to peers, how to distinguish between the role of peer and mental health professional, and how to ensure proper care for both the peer and the veteran they support.

Method

A rapid narrative literature review was conducted to determine the benefits of employing peers and the risk and protective factors relevant to their selection, training and mental health support. The research questions were:

- What are the benefits and risks to mental health support organisations in employing mental health peers to work with those who have mental health difficulties within the veteran community?

- What are best practice or consensus considerations for the selection, training, employment and care of peers within the veteran community?

A rapid narrative literature review is a literature review with the following limitations:

Rapid: The scope of search terms was narrowed to a specific set that would yield a manageable number of documents to review within the timeline. The current search was limited to information in relation to the use of peers who have a lived experience of mental illness. A review was conducted of documents written within the last decade (2009–2019) only. A search of the reference list of articles was made if the list contained references within the last decade. PsycINFO and PubMED databases were searched for articles retrieved within the past decade (2009–Dec 2019). Only English language articles from peer-reviewed journals were included.

Narrative: No meta-analysis of data was made and only limited categorisation of materials completed, and there is no table outlining all references. A narrative review describes and critically analyses the state of the science on the topic. The search was conducted in two parts in order to ensure that best practice or consensus statements were retrieved from the mental health peer setting, both within and external to veteran organisations.

Firstly, a search for evidence related to frameworks for selecting, employing and utilising mental health peers was conducted. Search terms used were based on a previously developed framework for best practice in organisational peer-support models—that is, the use of work colleagues to provide mental health support to their colleagues.6 This commonly occurs within first responder organisations. Results were reviewed to inform the utilisation of peer support within a mental health or welfare service.

Secondly, a search was conducted for any literature related to peer support and mental health in veteran populations, both in Australia and internationally. This search removed the necessity for articles to include information on goals, selection, training, employment or care of peers, to ensure that any published veteran peer program was reviewed.

Table 1. Search variables for the literature review on veteran mental health peers

| SECTION | LITERATURE SEARCH VARIABLES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bracket 1 (Title) |

Bracket 2 (Subject terms |

Bracket 3 Part A (Title) |

Bracket 3 Part B (Title) |

|

| Target demographic | ‘Peer support’ | ‘Mental health’ | ||

| Goals of peer support | Goals Risk Pathways |

|||

| Selection | Selection Assessment Criteria |

|||

| Training and accreditation | Training Accreditation Skills Referral Standards |

|||

| Professionals | Governance Supervision |

|||

| Role | Role | |||

| Access | Access | |||

| Self-care | Self-care | |||

| Evaluation | Evaluation | |||

| Veterans | Veteran* | |||

Results

Part A: General mental health peer-support literature overview

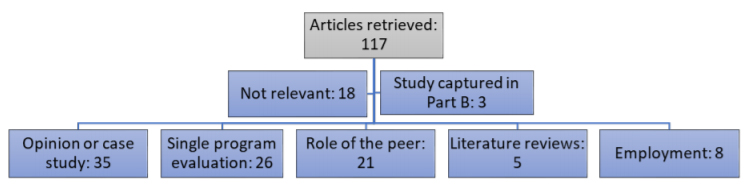

The search returned 117 articles and abstracts were reviewed for their relevance to this literature review. Articles were grouped inductively according to the type of information provided. These groups are described in further detail below.

Figure 1. Articles retrieved according to search in Table 1, Part A

Opinion piece or case study

Much of the literature on mental health peer support appears to be in the early stage of development. Many of the articles retrieved were descriptions of single intervention designs. Several others were opinion pieces regarding the burgeoning field of peer support and the inconsistencies in interpretation of the goals, role and utility of peers in mental health services.7

Single program evaluation

Some of the single program interventions also had preliminary evaluation, including some with 12-month follow up.8 However, the process for evaluation of interventions remains in its infancy, with several qualitative studies, few control group measurements and many evaluations of low power or quality.

Role of the peer

The role of the peer changes according to organisational needs. Some organisations use peers separate to a multidisciplinary team, in voluntary education or advice roles,9 for example, one study discusses the importance of peers pursuing their own recovery journey, thus their work being a form of professional development.10 A number of authors commented on the lack of role clarity for those working as peers.11, 12 All articles, except one identified, used a qualitative approach, looking at the experience of peers already volunteering or working, and sometimes the allied health staff working with them, to identify the core elements of the role.

There appears to be consensus in the literature regarding the role of a peer as qualitatively different from that of professional and para-professional staff working in mental health. The unique nature of the lived-experience worker uses self-disclosure and personal interaction in a person-centred (or recovery-centred) philosophy. One article described how the occupational identity of a peer evolves through the interaction between their lived experience, their training and their engagement in the practice environment.13 It may be that this is more important for the peer, as most paid staff enter a program with an established sense of professional/occupational identity. Thus, time spent allowing for the development of this occupational identity should be a core component of a peer induction program.

Literature reviews

A review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on mental health peers within health organisations from 1995–2010 concluded that randomised trials to date used variable outcome measures and showed inconsistent findings as to any benefit of peers, with some potential increase in social support for consumers.14 There was limited data on the benefit of engaging in a peer role, including aiding their recovery process. Given the comprehensiveness of that study, the current literature review focused only on literature published subsequent to that review.

A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on the impact of support work on peers found two important themes: reframing of identity, and therapeutic use of self.15 Firstly, peer work allows for a reframing of the past to give meaning to peers’ suffering and experiences. Secondly, peers identified the unique aspect of their role as being able to use their self-disclosure in a therapeutic way. This results in challenges related to boundaries but also has the benefit of a unique role in the system. Another study focused on the experiences of peers, their non-peer colleagues and the recipients of peer-support services,16 with similar conclusions. A further review looked at outcomes for online peer support for young people with mental health problems.16

A 2018 general review of the literature on peers concluded that a lack of evidence precludes strong recommendations from being made.17 However, the author provides a summary of areas for consideration in developing a program: role, boundaries, professionalism expectations, supervisory direction, training and support needs.

Employment of peers

A large scale Delphi study of the opinions of peers obtained a list of factors addressing the role, benefits, barriers and support needs.18 Poor career prospects were considered a barrier to taking up the role. Benefits included improved peer wellbeing, making a contribution, pay, learning and social connectedness. Support needs were consistent with other material, including training, support and supervision, and an organisation that values and enables peer work to occur. Peer work is considered unique and separate to mental health work, with a focus on personal disclosure, connection with consumers and two-way benefits to the interactions. Peers were explicit that the organisation needs to support those aspects for the program to be beneficial.

A systematic literature review and large scale Delphi study of peers and experts in Portugal19 assessed statements consistent with those in the published Delphi study on the use of peers in highrisk organisations (employees who support other colleagues in times of exposure to critical incidents).6 This resulted in a list of key statements that support a peer framework within the following categories: (a) goals and principles of peer support; (b) selection of peers; (c) training and accreditation; (d) role of mental health professionals; (e) role of peers; (f) access to peers; (g) looking after peers; and (h) program evaluation. A consensus of all US states who were using peers within their government mental health services20 outlines 25 principles of peer support, including clarity in role, competencies, training and certification. This statement makes several recommendations regarding training:

- trauma-informed care training for peers

- a train-the-trainer program for peer-support specialists

- a peer-support code of conduct that guides peer work

- training for non-peer staff in recovery-focused care

- access to consumer-run organisations that support peers.

This focus on training for the whole workforce, not just peers, ahead of a peer program, is backed up by a systematic literature review on barriers to successful peer implementation.21 This identifies organisational culture as the main barrier to integrating peers into a mental health workforce, followed by training and role definition barriers.

One study described the development of the peer-support workforce within the South Australian Government mental health care system.22 This model identified similar training and preparation steps to the above review articles. It provides detail on the knowledge and skills requirements identified for peers within this system, including the need for an understanding of a social justice and recovery model in which the peer can deal with stigma and discrimination, promote recovery and social inclusion, and research and share information on mental health support services. It also emphasises self-care strategies, the ability to set boundaries, recognise own triggers and maintain wellness. Another study describes a training program for peers that covers these concepts.23 One quantitative study found that teaching basic counselling skills to peers increases their use of nonspecific therapy skills without reducing acceptance of their role or perceived empathy by the consumer.24

One framework for the employment of peers was developed within the UK health service.25 It combined recommendations from an expert panel of peers and peer supervisors with the known literature at the time. This aimed to strike a balance between the need for quality control in service delivery and the need to maintain the peer as an informal source of support. The five principles developed include: supporting the development of a relationship based on shared experiences; ensuring mutuality and reciprocity; the application of experiential knowledge; enabling peers to exercise leadership and choice in their role; and empowering peers to make use of their strengths.

Part B: Veteran-specific mental health peer-support literature overview

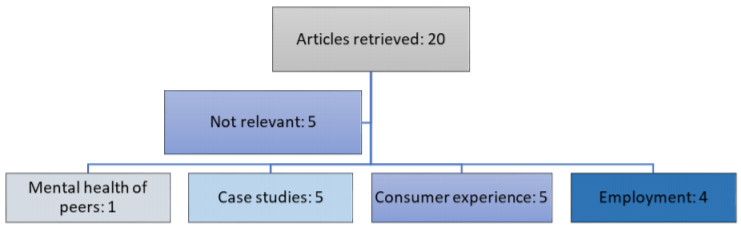

Twenty articles were retrieved regarding veteran peer programs. One study was from Australia and one from the UK; the remaining studies were from the US, with overlap in authors and programs studied.

Figure 2. Articles retrieved according to search in Table 1, Part B.

Case studies

Five case studies of the implementation of peers into mental health services were described. Two innovative uses of peers were described, including the use of peers to improve engagement in online therapy and peer telephone support.26, 27 Two studies described the use of peers to engage hard-to-reach veterans in rural areas or post-incarceration.28, 29 The consumer experience of a peer-support group facilitated by a peer, also focused on gaining assistance from nontrained peers, is described in two studies that do not differentiate between the benefits of a peer and the benefits of being in a peer-support group.30, 31

Mental health of peers

One article described the impact on peers working in populations with poor mental health. The study used quantitative measures and found that mental health and burnout outcomes were similar to mental health professionals and para-professionals working in the same organisation.32

Consumer experience

Along with anticipated changes from an outdoor education style program (for example, personal competence), one study also found changes in mental health symptom reporting when the program was peer-led.33 A report on an inpatient PTSD treatment program, which was supplemented by peers, found that symptoms and recovery attitudes are affected by perceived support from peers, other participants and other staff in equal measure.34 However, another study found that peers conducting a pre-treatment intervention resulted in greater completion rates than those conducted by mental health professionals. 35 When asked about their experience of a peer program at a specialist veteran mental health clinic, consumers reported themes associated with a reduction in barriers to entry at the facility, such as being a welcoming face and connecting veterans with staff.36

Employment of peers

A case study of the implementation of a peer program stressed the need for organisational buy-in of a program and suggesting organisational change strategies to assist with this.37 A study looking at peer support for homeless veterans investigated the actual rate of use of a peer service by consumers. The authors found that approximately once-a-month contact with peers was the most common rate of usage, with older veterans more likely to engage with peers.38 Two studies of peer programs found that recovery attitudes are positively associated with the receptivity of peer work by the organisation’s nonpeer staff.39, 40

Table 2. Veteran-specific peer articles identified

| Country | Authors | Setting | Participants | Method | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | Azevedo, Ramirez (29) | Veteran peersupport groups for sequelae of violent, traumatic experiences | 29 peersupport group participants, 1 peer specialist | Qualitative | Key themes: violence in military training not acceptable in civilian life; peer support creates the trust to speak freely; skills are taught to defuse violence; veteran peer-support specialist relationship is multidimensional. |

| AUS | Bird (32) | Australian peer outdoor support therapy program for contemporary veterans | 14 veterans in a peerled outdoor education activity | Quantitative (no control group) and qualitative | Reductions in depression, anxiety and stress maintained to two-month follow up. Key themes: sense of shared identity, involvement, belonging, increased self-determination and personal competence. |

| US | Chinman, Shoai (36) | Peer-support technicians in the Veterans Administration | Nil | Development of protocol | N/A |

| US | Ellison, Schutt (37) | Homeless veterans with mental health conditions and substance use | 50 veterans receiving peer support | Quantitative (no control group) | Consider yardsticks of monthly services for up to 6 months. Consider varying levels of intensity according to need. |

| US | Jain, Hernandez (27) | Peer-support program for veterans in rural areas | Case study | Qualitative | N/A |

| US | Jain, McLean (33) | Residential rehabilitation program for veterans with PTSD | 55 PTSD inpatients receiving peer support | Quantitative (no control group) | Greater perceived support from peers, other veterans and staff were associated with improvements from intake to discharge in recovery attitudes and PTSD symptoms. |

| US | Joseph, Hernandez (25) | Peer-support telephone outreach | Case study of program recruiting 34 veterans | Quantitative (no control group) | 23% of veterans contacted ultimately engaged in the peer-support groups; this subpopulation was receiving no other mental health care. |

| US | Nelson, Lusk (34) | CBT Pre-treatment intervention | 352 participants in a CBT pre-treatment group | Quantitative (Program Support Assistant as control group) | Use of peers predicts completion in pre-treatment group overuse of program support assistants. |

| US | Park, Chang (31) | Veterans Health Administration (VHA) peer-support specialists | 152 peers | Quantitative (no control group) | Peers reported similar levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment to published scores for VHA mental health workers. |

| US | Ray, Kemp (26) | Computer-delivered CBT | 24 veterans with depression or anxiety | Qualitative | Key themes: veteran preferences for use of peers in practical aspects emotional support and application of learning to ‘real life’ problems. |

| US | Simmons, Fincke (28) | Veterans who are post-incarceration | Case study | Study protocol | N/A |

| US | Stefanovics, Drebing (38) | VHA peer-support specialists and supervisors | 141 peers and 146 peer supervisors | Quantitative (no control group) | Level of perceived receptivity was high for peers and supervisors and correlated with recovery attitudes. |

| US | Weir et al. 2019 | Peer-support workers at a specialist veteran mental health clinic | 18 veterans, peers or clinicians | Qualitative | Key themes: positive first impression, understanding professional friend, helpful and supportive connector, an open door. |

| US | Shepardson, Johnson (39) | VHA primary care mental health integration service | 7 peers, 6 peer supervisors, 12 clinicians | Qualitative | Key barriers: program functioning, administrative support, role confusion, negative stakeholder attitudes. Key facilitators: administrative support, program functioning, team cohesion, stakeholder buy-in, access/visibility, evidence of success. |

| US | Kumar, Azevedo (30) | Outpatient program for veterans with PTSD | 29 participants with PTSD | Qualitative | Key themes: acceptance of PTSD into daily life and identity; structural and emergent support. |

Discussion

Limitations of this study

As described, this study was restricted to a rapid narrative review in order to determine the current status of the field rapidly. This brings necessary limitations in the scope of articles that can be obtained and reviewed. While the field of peer support is mostly limited to work conducted since the early 1990s, there is potential that some early instructive work has not been reviewed. In addition, the review is limited to a description of publications. While it attempts to distinguish case studies— that is, descriptions of single peer programs with no evaluative content—it does not make any other attempt at evaluating the quality of the studies. To more accurately make evidence-based decisions regarding future programs, it may be useful to subject the field to more rigorous testing of the quality of evidence.

The field of veteran peer support is a burgeoning one; however, a lag between the use of peers and rigorous review of outcomes remains. As with all new fields, a focus on case studies, training and initial qualitative understanding of the benefits comprise a large majority of the studies. Despite the widespread consensus of the need to adequately support peers, there are almost no studies aimed at measuring psychological risk to peers in their role. However, there are several consensus positions in regards to the implementation of a peer program, which are supported by limited but consistent findings. These relate to the activities of a veterans mental health peer, the perceived benefits and some guidance on the employment of peers.

Veteran-specific tasks

In relation to the use of peers, specifically within the veteran space, there do not appear to be any published findings that suggest the general guidelines for mental health peers would differ. A veteran peer straddles the divide between a peer who has a specific lived experience of mental health difficulties and an organisational peer who has a lived experience of working in the same organisation. In this case, a veteran peer may not have a mental health history, but has an experience of going through the process of transition out of military life. There is no current research that investigates the qualitative difference of this process. In the meantime, consensus on the activities of a peer includes two essential points that may have to be interpreted for the veteran peer to

accommodate their specific context:

- self-disclosure about their own recovery journey in a therapeutic way

- personal, informal interaction in a person-centred way.

Perceived benefits

Although there is no current evidence for the benefit of peers, there does appear to be consensus on a number of perceived benefits of peer programs to consumers:

- increased engagement with services

- increased social support

- reduced mental health stigma and discrimination

- increased perceived support from the service

- engaged hard-to-reach clients

- improved recovery attitudes

- increased completion rate for centre programs.

In addition, within the general mental health setting and with the used of peers who have a lived experience of a mental health disorder, there are additional perceived benefits to peers operating in the role:

- pursue own transition journey

- reframing their mental health difficulties in a recovery model

- social connectedness.

Employment of peers

A synthesis of information from the general mental health peer field, removing factors which are not relevant to a veteran environment, is listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Synthesis of best practice framework for veteran mental health peers

| Goals and principles | Selection | Training and accreditation | Role of mental health professionals | Role of peer supporters | Organisational issues | Client access to peers | Looking after peer supporters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

This article provides a summary of evidence-informed guidelines for the selection, training and employment of peers within veteran settings, and may be useful for organisations who are considering the employment of veteran peers. There is a need for research that can establish the benefits of peer programs, either in comparison to organisations who do not have programs or in comparison to other initiatives that organisational resources could be used for, including the use of paid staff.

Corresponding Author: Carolyn Deans

carolyn.deans@unimelb.edu.au

Authors: C Deans¹

Author Affiliations: 1 Phoenix Australia