Abstract

Background: Veterans frequently report barriers to accessing and adhering to first-line treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Online delivery of an evidence-based intervention by a peer-developed program may aid in overcoming these barriers.

Purpose: This study evaluated the ‘Post War: Survive to Thrive Program’, an online, peer developed and delivered program, designed to assist with the management of commonly occurring mental health symptoms among veterans.

Material and Methods: Former Australian Defence Force (ADF) members (n = 29) completed the program and were assessed at pre-intervention, three months post-commencement of the program (post-intervention) and six months post-commencement (follow-up). Changes in mental health symptoms were assessed using the DASS-21 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, and changes in overall levels of happiness were assessed using the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire.

Results: Repeated measures ANOVAs indicated significant main effects across time for all constructs measured. Post-hoc comparisons indicated depression, anxiety, stress and posttraumatic stress symptoms were significantly lower at post-intervention and follow-up compared to pre- intervention. Happiness scores were significantly higher at post-intervention and follow-up compared to pre-intervention. There were no significant differences between post-intervention and follow-up, indicating maintenance of treatment gains.

Conclusions: To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to report an evaluation of an online therapy program utilising a peer developed and facilitated psychological intervention with a veteran population. Findings demonstrated a positive trend, indicating the Post War: Survive to Thrive Online Program may be beneficial for veterans; however, a controlled trial with a larger sample is required to determine effectiveness of the program.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, online, military personnel, treatment, veteran mental health Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Funding: This work was supported by RSL Queensland who funded this study as part of the Veteran Mental Health Initiative at the Gallipoli Medical Research Institute.

Evaluation of the online, peer delivered ‘Post War: Survive to Thrive Program’ for Veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder

Following exposure to a traumatic event, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterised by intrusive memories and nightmares, avoidance of stimuli reminiscent of the trauma, negative changes in mood, and heightened physiological arousal and reactivity1. Previous research has demonstrated prevalence rates of PTSD are greater in current serving and service veterans compared to community based populations; 5.49% to 20.9%2-6 compared to 1.3 to 12.2% respectively7. PTSD is also associated with comorbid psychiatric conditions, including generalised anxiety and depressive disorders8, as well as physical health problems9.

Current first-line evidence-based treatments for PTSD include Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT), Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PET), and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing Therapy (EMDR)10. While such interventions are utilised within the veteran population, there are particular barriers to engaging in face-to-face treatments relevant to this population. Barriers reported by this population include access difficulties, treatment beliefs, as well as stigma and concerns about potential social consequences8,11. Given the elevated prevalence rates of PTSD and other mental health conditions in veteran populations, it is imperative to develop tailored interventions that overcome these barriers.

Online interventions for Veterans with PTSD

To address potential barriers to treatment access, innovations in technology have seen the integration of digital-mediated platforms into the screening and treatment of PTSD12-14. Notable preliminary evidence from recent review studies has demonstrated the efficacy of internet-based interventions in the treatment of PTSD15,16 and symptoms of depression and anxiety17. In terms of veteran specific interventions for PTSD, a number of online programs have been recently evaluated12-14.

In particular, an online resource developed specifically for serving members and veterans, the ‘Posttraumatic Stress Workshop’12, was assessed with promising findings13,18.

Initially, a multiple-baseline single-case design (n = 11) provided preliminary support for the workshop, with statistically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms for 4 participants, and significant overall reductions in PTSD symptoms between enrolment and post-intervention for 5 participants18. Qualitative feedback found that while participants were satisfied with the module content, they desired the inclusion of a peer-support component.18

An additional study assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of the online workshop, recruiting veterans without access to traditional treatments for PTSD (n = 24)13. Weekly telephone contact with clinic staff was included to assess symptoms and promote adherence. Similar findings to the previous study were noted, with 40% of participants reporting a reliable decrease in PTSD symptoms; however, the study had high dropout rates and failed to include a follow-up assessment13.

Hobfoll et al.14 conducted a randomised controlled trial (n = 303) evaluating the efficacy of an interactive seven-module, online CBT intervention, targeting treatment of mild to moderate PTSD and comorbid depression among veterans. The intervention also included optional engagements in an online peer chat (with trained military veterans who provided supportive guidance only) and a community message board. The study found that participants in the treatment condition (n = 209) reported a significant reduction in PTSD and depressive symptoms at 12 weeks follow-up, compared with veterans in the treatment as usual condition (n = 94), with moderate effect sizes for both PTSD and depression14. The study authors were unable to ascertain if accessing peer support through online peer chat or message boards had an impact on these outcomes. However, the authors note that the retention rate in this study was higher than other web-based intervention studies that do not include peer support, and concluded that the addition of this support may have reduced participant attrition14.

Peer support

Peer support is typically defined as ‘a peer with a history of mental illness who, having experienced significant improvement in their condition, offers services and support to a peer considered to be not as far along in their own recovery process’19. Previous research has noted standard internet-based interventions often report low completion rates and the addition of peer support may help reduce the likelihood of attrition20. Jain et al.19 conducted a qualitative study to examine the mechanisms through which peer support may be helpful to veterans with PTSD. The themes identified were: (1) peer support contributes to feelings of positive social connectedness; (2) role modelling by the peer support provider can instil hope that recovery from PTSD is possible; (3) peer support can destigmatise the decision to seek mental health treatment and increase engagement with treatment; and (4) peer support can assist with orienting and navigating the veteran to mental health treatment19.

In addition, a pilot study examined the feasibility of utilising a peer-support model to increase engagement and completion of an eight module online CBT intervention for veterans with a diagnosed depressive disorder21. The peer-support model involved pairing program participants with a veteran who had completed the program, who provided weekly phone contact to offer support and guidance. Assessment of depression was conducted at pre-intervention, and at 4- and 8-week follow-up. The results indicated that at 8 weeks, symptom reduction and completion rates were comparable to results of brief individual, group CBT and staff assisted CBT interventions21. This study provides evidence of the role peer support may play in improving engagement and successful completion of online programs. This study used an established model of peer support where the peer is utilised as an ancillary source of guidance and support with the goal of increasing engagement with the intervention.

The Survive to Thrive Program

The preceding review demonstrates evidence of effectiveness of online psychological interventions for the treatment of PTSD and commonly occurring comorbid conditions15-17. However, there have been limited studies using veteran populations13,14,18. The use of peer support has also demonstrated additional benefits14,19-21; however, it appears that no studies to date have evaluated peer developed and delivered interventions within a veteran population. Given the high prevalence of PTSD in military veteran populations, barriers to treatment identified, as well as the potential benefits of peer support, further research determining the effectiveness of online mental health interventions for the treatment of PTSD and common comorbid conditions in this population is important. The willingness to utilise peers with diagnosed mental health conditions, in development and implementation roles, may represent an innovative approach to overcoming barriers to treatment in veteran populations.

The Post War: Survive to Thrive Program is unique to previously evaluated online psychological treatments as it was developed and delivered by a non-mental health trained peer facilitator, who previously served in the military and has experienced PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms. The program is comprised of nine modules of online psychoeducation, motivational speaking and coaching, CBT skills training and mindfulness skills training. A former infantry soldier of the Australian Army developed the program, with technical support from an online training provider. It was developed following first-hand military experience and incidence of PTSD, depression and anxiety, as well as prior clinical mental health treatment. The program was designed for current serving personnel and service veterans with the aim of assisting participants to understand common mental health conditions arising from military service and training, and how they may impact behaviour. The objective and aim of the program (as stated by the program developer/facilitator) is to ‘teach current and ex-service personnel to accept responsibility for the role they can have in their own self-development, growth, recovery, and transitional success back to civilian life’ and ‘prepare participants and their family for common stressors and scenarios while dealing with PTSD, depression and anxiety, and adversities arising from military service’. While this program is currently being offered to the veteran community, the effectiveness of the intervention has not been evaluated.

Aim of the current study

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the psychological outcomes of participants of the Post War: Survive to Thrive Program across the domains of depression, anxiety, stress, posttraumatic stress, and happiness and wellbeing. These domains were assessed with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) and Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ). In addition, this study aims to assess the retention rates of this peer developed and delivered program. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first evaluation of an online therapy program with a peer as the content creator and facilitator with a veteran population; therefore, no hypotheses were proposed.

Method

Study design

The study was a non-controlled, within-subject, longitudinal open trial, with psychometric assessment at three time points: pre-intervention, three months following commencement of the program (post-intervention), and six months following commencement of the program (follow-up). Given the lack of prior evidence regarding effectiveness of this novel intervention (which was not developed by the authors), a small, non-controlled open trial was deemed the most suitable approach in assessing utility, retention and potential treatment gains.

Intervention content

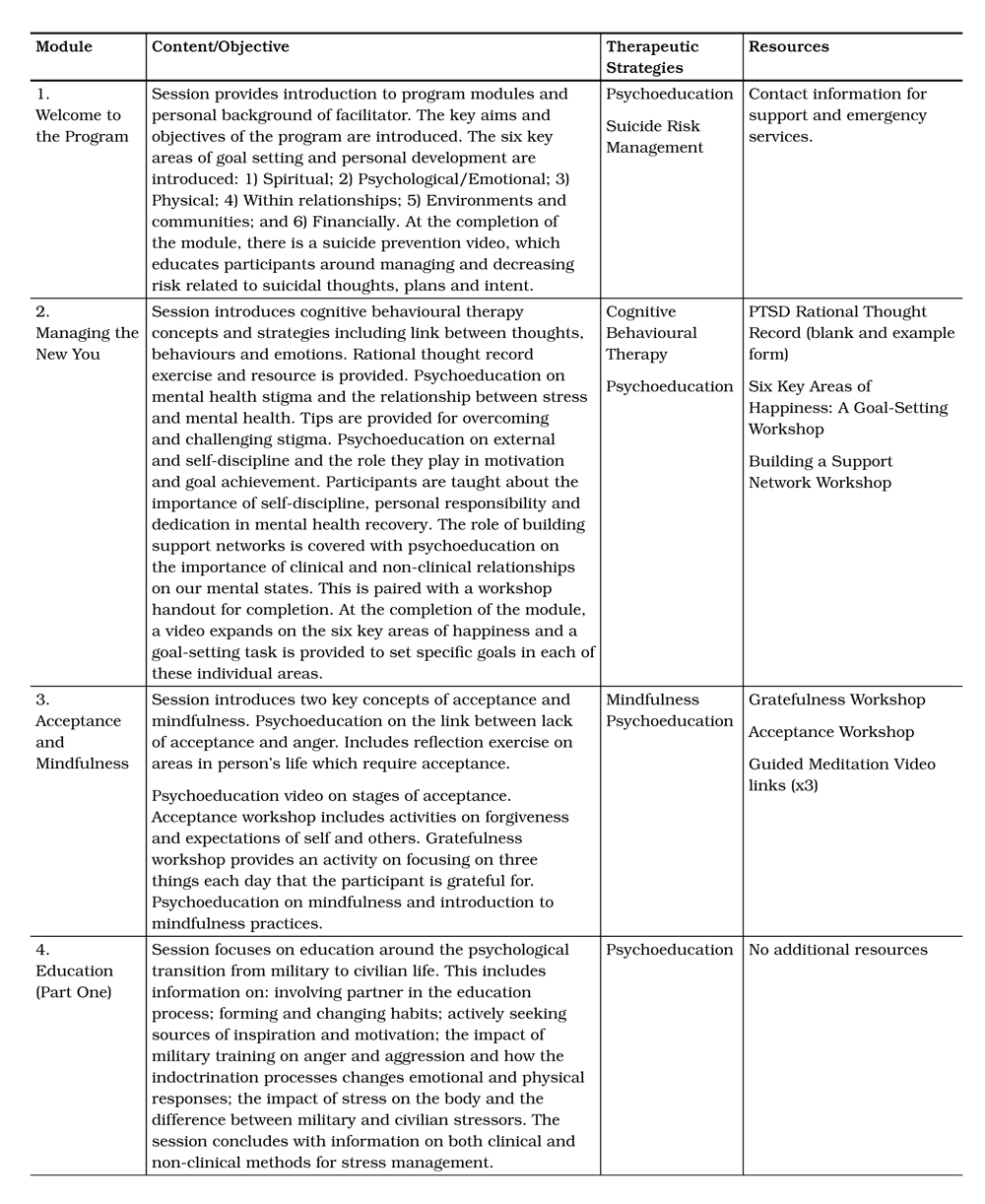

The program is separated into 9 modules that focus on (1) ‘Surviving Methods’ (Modules 1–5) and (2) ‘Thriving Methods’ (Modules 6–9). Table 1 provides an overview of specific module content. Participants utilising the program progress through the nine modules at their own pace and complete each module individually. There is no specified lag time between modules and the program is expected to take no longer than three months to complete. Various educational mediums are utilised in the delivery of the content including videos, slides and printable resources. The modules are pre-recorded and include video content accompanied by written tasks. The peer component includes viewing videos of a veteran (the program developer and facilitator) discussing his own experiences with mental health and describing what strategies have aided his recovery. The only additional contact made between the peer and the participants was organisational (i.e. providing program logins, reminders to complete measures and reminders to login).

Recruitment of participants

Ethics approval was obtained from The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) Human Research Ethics Committee (EO16/006). Potential participants were recruited from two ex-service organisations. Both signed and electronic consent was gained prior to commencement of the program. The inclusion criteria for eligibility to participate in the study were: (1) Prior service in the military; and (2) Over 18 years of age. The exclusion criterion included: (1) Current hospitalisation for treatment of a mental health condition. Participants did not receive payment for completion of the modules or participation in this study.

Study measures

Demographic characteristics

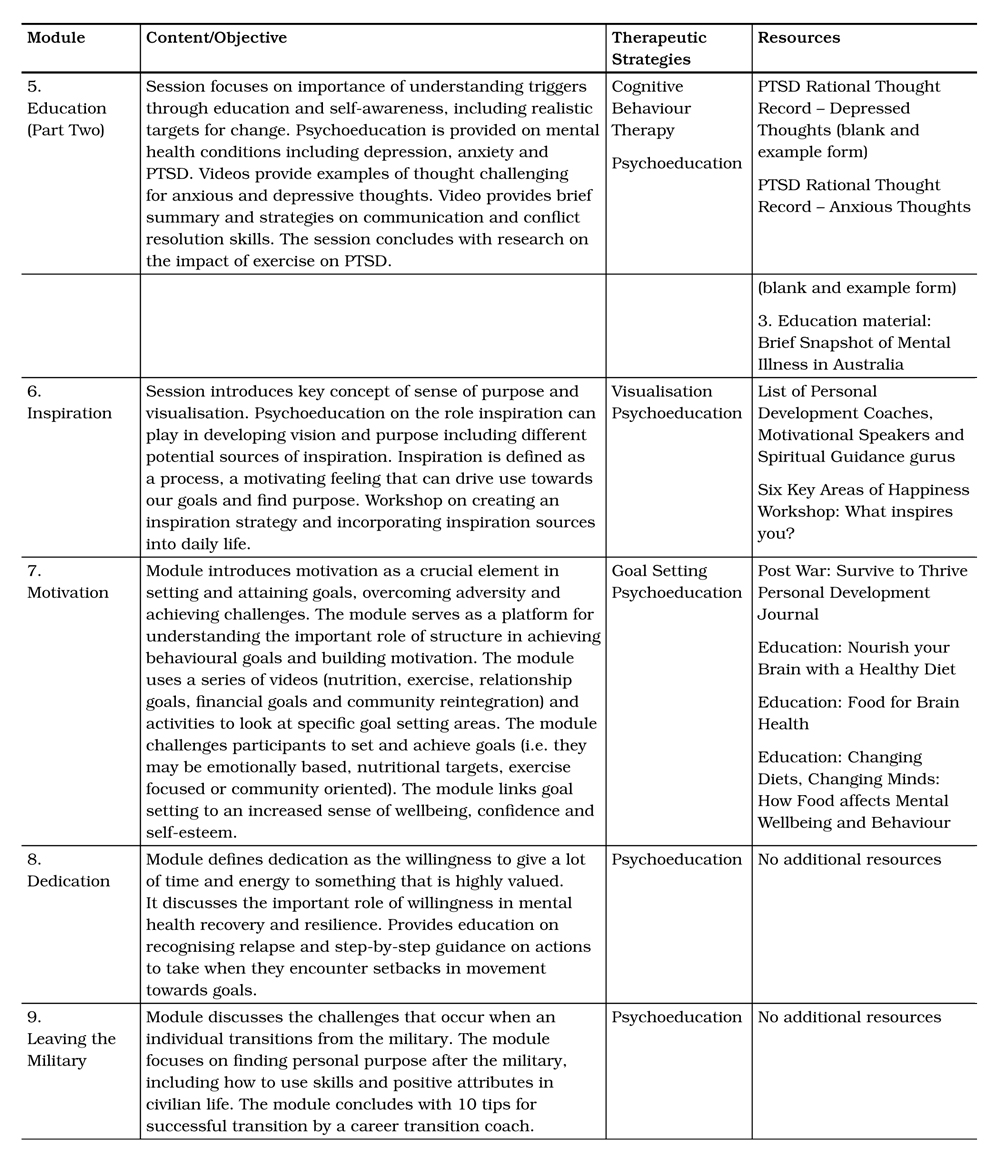

Participants were asked to report their age, gender, marital status and employment status. Service information was also requested including length and branch of service and if they were medically discharged. Additionally, participants were asked to report if they had been diagnosed with a psychological condition and had ever received psychological treatment for this condition.

Psychological outcome measures

Depression, anxiety and stress levels were measured with the DASS-21. The DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire with 3 subscales measuring depression, anxiety and stress22. Test takers rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale according to how much they were affected by the symptom over the past week. Higher scores on subscales indicate greater depression, anxiety and stress levels. The scale has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in previous research22,23 and excellent internal consistency in this study (α = 0.96).

Presence and severity of PTSD symptoms were measured with the PCL-5. The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD24. Test takers are asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale according to how much they were affected by the symptom over the past month. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties and is used regularly for research purposes including monitoring symptom change during and after treatment, screening individuals for PTSD and making a provisional PTSD diagnosis24-26. The measure demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this study (α = 0.95).

Participants’ subjective happiness and wellbeing was measured with the 29-item self-report OHQ27. Test takers are presented with statements and asked to rate each item along a 6-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating greater levels of happiness. Previous research has reported this measure has good psychometric properties27,28 and it demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this study (α = 0.94).

Data collection

Outcome measures were developed using online software. Following informed consent, a link to the online questionnaires was sent to participants to complete at each assessment point (pre-intervention, post-intervention and follow-up). The program developer and online training provider managed all program aspects and logistics over this time.

Statistical analysis

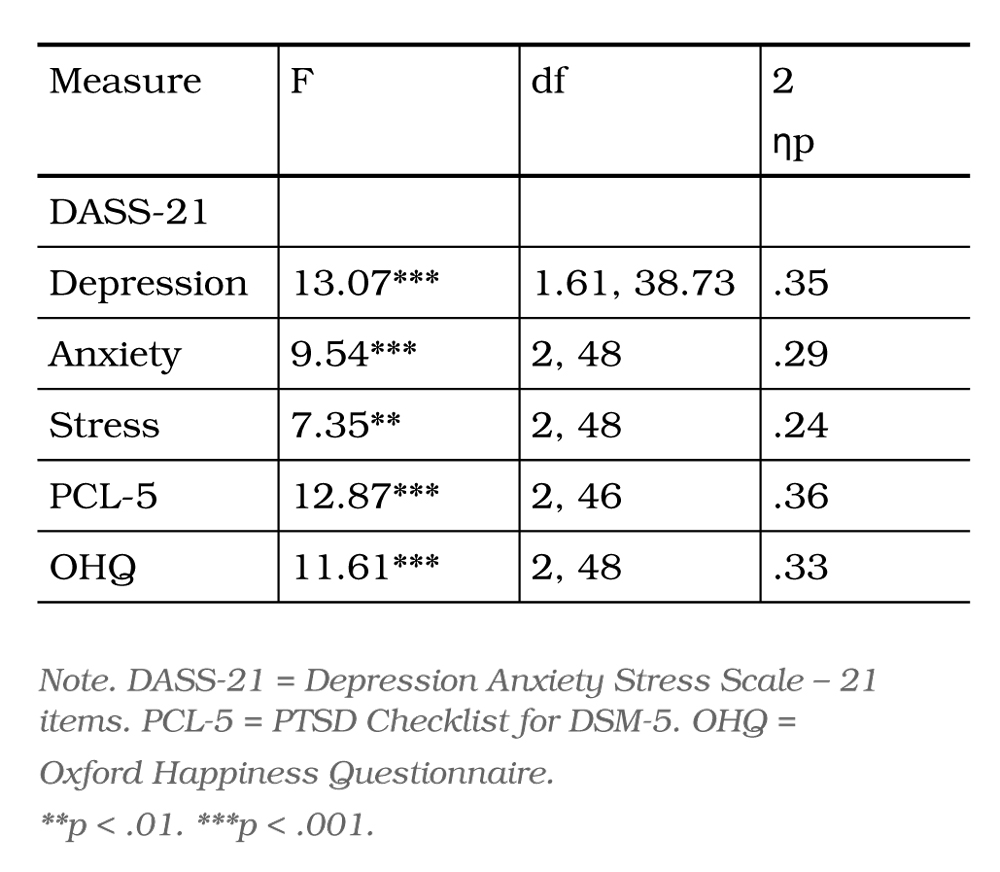

Statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24. Descriptive analysis was carried out through examination of means and standard deviations, and a series of one-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to examine if significant changes occurred between each assessment time point (pre-intervention, post-intervention, follow-up) on the DASS-21 subscales, PCL-5 and OHQ.

Significant main effects were further explored post-hoc with paired-samples t-tests. To account for multiple testing, a Bonferroni correction was applied and the significance level was set at p < .017. Effect sizes were examined and interpreted utilising Cohen’s29 d guidelines; r = 0.2 (small effect), r = 0.5 (medium effect), r = 0.8 (large effect). Due to a computer error, scores on Item 7 of the PCL-5 were not recorded at pre-intervention or post-intervention. Therefore, analyses involving the PCL-5 included summed scores with this item excluded. Inspection of descriptive frequencies, histograms, as well as skewness and kurtosis statistics for the total scale scores revealed adequate normality. The assumption of homogeneity of sphericity was upheld for all analyses except the DASS-21 Depression subscale. For this variable, Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to account for this violation.

Table 1: Module Content of Post War: Survive to Thrive Program

Results

Study sample and retention rates

A total of 29 participants completed the program, and all were former ADF personnel. Zero participants dropped out of the program. Participant demographic information is presented in Table 2. The mean age of participants was 4228 (SD = 9.67) and the majority of participants were in the 31–50 year age group (72.41%). There were high rates of participants who reported they had been diagnosed with a psychological condition (75.9%) and had previously received treatment for that condition (89.7%). Pre-intervention scores on the PCL-5 ranged from 14–71 and all participants had experienced at least 3 clinical level symptoms of PTSD in the month prior to study participation (i.e. a score of 2 or above). In addition, 20 participants (68.97%) scored or exceeded the clinical cut-point score (> 33) on the PCL-5 at pre-intervention. Additionally, pre-intervention mean scores on the DASS-21 indicated participants were in the ‘Severe’ range on the depression and stress sub-scales and in the ‘Extremely severe’ range on the anxiety sub-scale. While program developers reported all 29 participants completed the program (100% intervention retention rate), three participants did not complete all outcome measures at post-intervention, one participant completed all outcome measures except the PCL-5 at post-intervention, and two participants did not complete outcome measures at follow-up (89.66%, 86.21% and 93.10% study retention rates respectively).

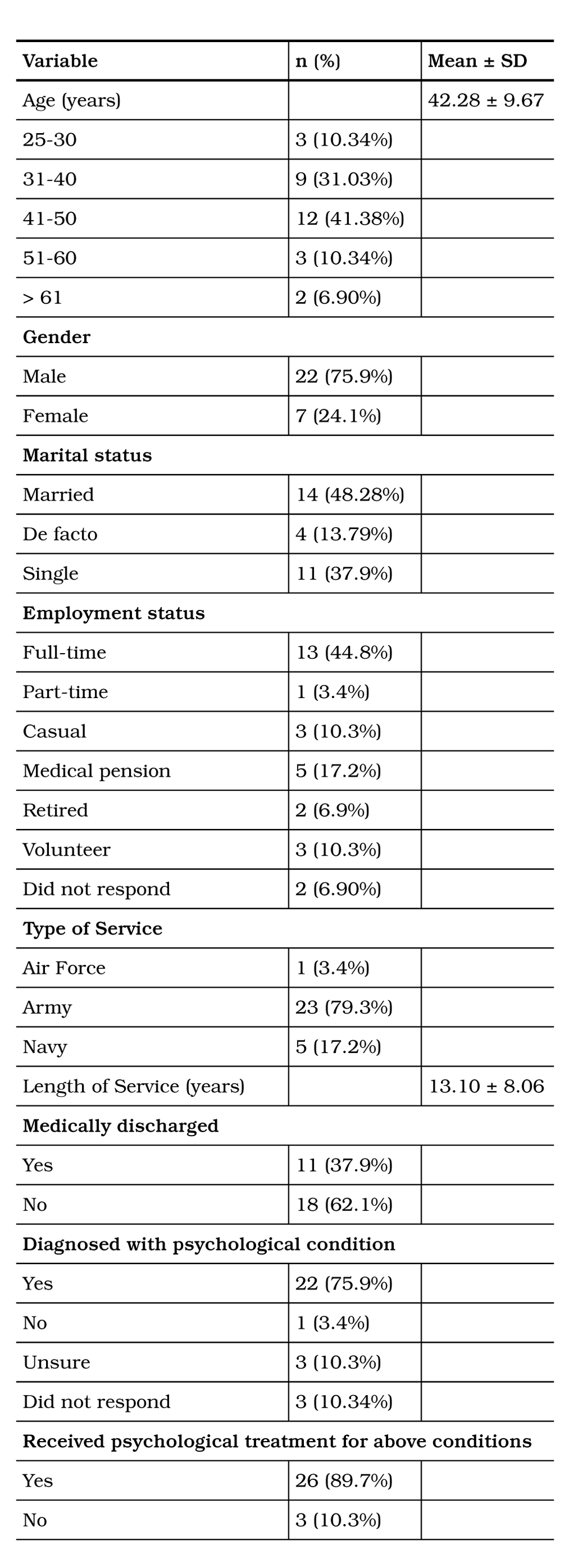

One-way repeated measures ANOVAs

A series of one-way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to compare scores on the psychological outcome measures across three assessment points: pre-intervention, post-intervention and follow-up.

Table 2: Participant demographic characteristics (N=29)

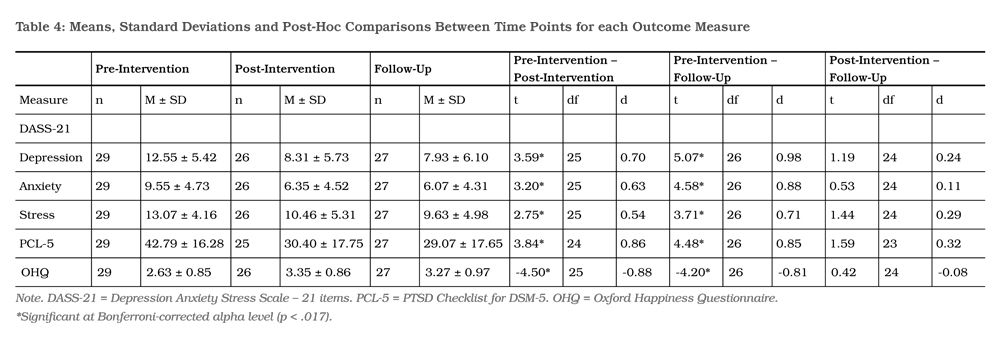

The results of these analyses are presented in Table 3 and indicate a significant main effect for each measure. Due to significant main effects, post-hoc comparisons were conducted. Means and standard deviations and the results of post-hoc comparisons between each assessment time point with effect sizes, are presented in Table 4.

Results revealed that scores on the DASS-21 subscales and PCL-5 were significantly lower at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention, and significantly lower at follow-up compared to pre-intervention. There were no significant differences in scores between post-intervention and follow-up, indicating reductions in psychological symptoms were maintained at six months.

All DASS-21 subscale means at post-intervention dropped to the ‘Moderate’ range and remained in this range six months later. Furthermore, from pre-intervention to post-intervention, the mean score on the PCL-5 reduced by greater than 10 points. According to author guidelines of the PCL for DSMIV, this indicates a ‘clinically significant’ change. While change scores for PCL-5 are currently being determined, it is expected that reliable and clinically meaningful change will be in a similar range24.

Finally, results revealed scores on the OHQ were significantly higher at post-intervention compared to pre-intervention, and significantly higher at followup compared to pre-intervention. There was no significant difference in OHQ scores between post-intervention and follow-up, indicating the increase in happiness and wellbeing was maintained at six months. For all significant differences, effect sizes were medium to large.

Table 3: Repeated Measures ANOVAs Comparing Scores on Measures Across Assessment Time Points

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of participants of the Post War: Survive to Thrive Program across the psychological domains of depression, anxiety, stress, post-traumatic stress, and happiness and wellbeing. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to report an evaluation of an online therapy program utilising a peer developed and facilitated psychological intervention with a veteran population. The sample had predominantly served in the army, been reportedly diagnosed with a psychological condition and had previously received treatment for that condition.

Overall, the results of the evaluation demonstrated a positive trend, indicating the Post War: Survive to Thrive Program may be beneficial for veteran participants. The self-reported psychological symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress and PTSD significantly reduced between pre- and post-intervention, with this change remaining stable six months following program commencement. Self-reported happiness and wellbeing also significantly improved between pre- and post-intervention and was maintained at follow-up. Effect sizes were large for symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and happiness and wellbeing, while the effect size for stress symptoms was moderate. Self-reported PTSD symptoms, on average, reduced by greater than 10 points, indicating a clinically significant change24.

These findings share consistencies with prior research that have demonstrated significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veteran populations using online psychological interventions13,14,18. With regards to the effect on PTSD symptoms within non-veteran samples, e-mental health interventions have evidenced similar positive outcomes15,16.

The results are also in line with the broader literature examining the efficacy of mental health e-interventions for the treatment of depression and anxiety17,30. The moderate to large effect sizes found for the mental health outcomes in the current study are in line with previous research14, 17. Retention rates in the current program were also strong, echoing previous findings demonstrating inclusion of peers in mental health interventions reduces attrition to online programs>sup>14, 20.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of the current research, it is important to consider the limitations associated with the research design and interpretation of outcomes. First, as this was a preliminary open trial, the study design was not blinded and did not include a control group. This means it cannot be concluded that the program was the mechanism of change that led to reductions in depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD symptoms, and an increase in happiness and wellbeing. Outcomes may be attributed to other non-controlled factors, such as the high rate of participation in previous therapeutic activities. Second, although comparable to similar pilot study research, the sample size for quantitative data analysis was small, limiting generalisability. Third, self-report measures are potentially biased with the risk of under or over reporting of symptom severity. It is also important to view the results in the context of the sample under discussion; approximately 90% of participants had reportedly engaged in psychological treatment prior to commencing the program. As such, it is unclear if a more clinically severe population, who have not received previous psychological treatment, would benefit from the lower intensity intervention offered by the Post War: Survive to Thrive Program. However, the high retention rate is positive and suggests strong engagement with the peer presenter and peer-developed content.

Future directions

Future research could proceed in a number of ways. Conducting a waitlist controlled trial and increasing the sample size would allow for greater certainty in identifying efficacy and mechanisms of change in the intervention. Additionally, the integration of mental health trained co-facilitators as well as providing therapist and/or peer feedback and assistance throughout the self-paced modules may be beneficial. Prior research has indicated that larger effect sizes are evidenced where therapist support is available (i.e. via email, skype etc.) 30 as well as positive outcomes with ‘live’ peer support14,18.

Conclusion

This study adds to the published literature examining effectiveness of online psychological therapy interventions for veterans with mental health complaints. It indicates the use of a non-mental health trained peer facilitator (with lived experience of PTSD, anxiety and depression), utilising CBT and coaching principles, may be associated with beneficial outcomes for participants, including the reduction of PTSD symptoms. It also provides further support for the use of a peer in improving retention for online mental health programs. This is particularly relevant in the delivery of mental health treatment to the veteran population in which there are often barriers preventing help-seeking, including geographical limitations and fear of stigma. A waitlist controlled trial with a larger sample size would help determine, with greater certainty, if the Post War: Survive to Thrive Program is an effective intervention for PTSD and associated mental health symptoms.

Corresponding Author: Madeline Romaniuk, romaniukm@ramsayhealth.com.au

Authors: M Romaniuk1,2,3 J Evans1, C Kidd1

Author Affiliations:

1 Gallipoli Medical Research Institute

2 University of Queensland

3 University of Southern Queensland