Sanders Marble

Keywords: Military Medicine/history; Military Medicine/organisation & administration; Preventive Medicine/history

On Tuesday, 21 April 1914 US sailors and Marines landed at Veracruz, Mexico. There were two days of sporadic fighting by the ‘Bluejackets’ and Marines followed by almost seven months of occupation by Army and Marine forces. The two services would draw limited lessons from the joint occupation, and thus of joint expeditionary medical support.

Background

On 19 February 1913 Gen. Victorianio Huerta overthrew the Mexican government and installed himself as president.1-3 US President Woodrow Wilson (inaugurated 4 March 1913) was shocked by the assassinations and determined “I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men.” In support of that policy, and as competition among Mexican factions turned into civil war, he would escalate the use of force. A series of actions by the Mexican government, and accidents by local Mexican troops, were interpreted as escalating provocations, and by April 1914 much of the Atlantic Fleet was off the Mexican coast not just to influence Mexican politics but for potential evacuation of American citizens. The flashpoint seemed to be Tampico, where a US Navy boat crew was detained when they approached the frontline between Mexican government and rebel forces. However, news of a shipment of machine guns and ammunition to Veracruz shifted US focus there; occupying Mexico’s main port would also block any efforts by Huerta to raise a loan secured by customs duties.

Combat and Casualty Care

The landings began at 11.00h, with 285 Bluejackets (sailors, executing their infantry training) from the USS Florida and 502 Marines, some from ships’ detachments and some from the 2nd Advance Base Regiment aboard a transport; the plan was only to occupy port facilities and not the entire city.2 The Mexican commander wanted no real resistance, and withdrew his roughly 1,000 regular infantry. However, a few chose to remain and he had armed over 300 paramilitaries of the ‘Society of the Defenders of the Port of Veracruz’ and also some ‘stripers’ (prisoners released from the jails and wearing their striped jail uniforms); an unknown number of civilians also took up arms against invading gringos.2 There was little organised fighting but much sniping; US casualties on the 21st were 4 dead and 20 wounded.2 (Mexican casualties were never certain since many never went through hospitals but were over 200 dead and 300 wounded and may have been double that).2 As improvised units, the ad hoc Bluejacket regiments and the Marines from the ships’ detachments had no formal medical support, but a doctor and some medical personnel from each ship went ashore. Aid stations were established in the Hotel Terminal and at the main pier with a total of six doctors.4 Naval medical personnel, officers and enlisted, were forward with the fighting men. HA1 William Zuiderveld dashed through a hail of gunfire to reach a wounded sailor; alone, and ignoring the fighting around him, Zuiderveld bandaged his comrade’s head and hauled him back to further aid, although ultimately to no avail.5 When firing broke out surgeon Middleton Stuart Elliott, Jr, left the aid station at the pier “ran to the firing line and helped to carry some of the wounded being brought out to the battle aid station.”5 Elliott’s small aid station, hardly safer than the front line, would ultimately treat 63 wounded Americans. The hospital ship USS Solace was off Tampico and the number of wounded taxed the medical personnel on the transport USS Prairie; British and Spanish naval surgeons (from their warships offshore to protect their nationals) came aboard and helped treat the wounded.3 Admiral Fletcher, the US commander, reported “Their assistance was gratefully accepted.”3 The resistance showed more American forces were needed, and most of the ships at Tampico were ordered south on the 21st, arriving before dawn on the 22nd.

Image 1: US troops enter Veracruz, April 1914. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

More Bluejackets and Marines came ashore, 6,000 by dark on the 22nd; the 3,000 Marines were roughly one-third of the Corps. The only major firefight developed after Bluejackets marched towards the Mexican Naval Academy not realising it was unsecured; a burst of fire hit many Americans and surgeon Cary Langhorne “unhesitatingly ran toward the wounded and retrieved a severely injured man from the attack.”5 After that fighting, it was clear the rest of the city had to be occupied, and the extra men could go house-by-house and also push out beyond the city to secure the water-treatment plant. The Marines took periodic casualties (13 killed and 41 wounded) in the house-clearing and the corpsmen with them also went forward under fire.3,4 Fighting an unidentifiable enemy was frustrating and the Atlantic Fleet commander commented “I rather think that as increasing numbers of our men were killed or wounded, that eventually it fared rather badly with those discovered with arms in hand on the spot from which shooting came”.2

At mid-day on the 22d the Solace arrived and received the American (and a few civilian) wounded.3 While the Solace had an X-ray machine, most care was conservative, keeping with surgical priorities of the time.6,7 Debridement was not normal (“greatly devitalised tissue” was allowed to slough off “and healing went on by granulation”), and abdominal surgery was considered more dangerous than observation in an era before sulfas, let alone antibiotics. While Solace’s doctors promptly performed a trephination, for at least two patients they waited several days to observe compound fractures and ended up with above-knee amputations due to infection. In early May, the Solace unloaded its civilian patients and returned to New York; it was an older ship and needed repairs. Instead, a Navy field hospital opened ashore to support the Marines; it operated alongside an Army field hospital.

Image 2: Putting patients from the Solace in a horse-drawn ambulance, New York City, May 1914. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

On 23 April an Army brigade at Galveston, Texas, had been warned for service in Mexico; embarked on the 24th, by the evening of 27 April it was afloat off Veracruz. It stayed afloat until 29 April until questions of command were resolved: would the Marines stay ashore and if so, who would be in command? The Cabinet met and President Wilson decided the Marines would stay and be under Army command. The next day the Army brigade landed, the sailors rejoined their ships, and Brigadier General Frederick Funston found himself in charge of Veracruz – in charge of all aspects of government, since Mexican law had stringent punishments for any public official who helped an invader. (Individuals could work for an invader, for instance as teamsters, but not as officials.) The US would stay in Veracruz an unknown amount of time to influence the Mexican civil war, but Funston received orders not to advance and avoid fighting if possible. (Lieutenant Douglas MacArthur would see his first action in early May, scouting for railway locomotives and having a daredevil return trip to Veracruz with four bullet holes in his clothes after shooting at least six Mexicans.)

Occupation and Public Health

Veracruz was a filthy city, with no municipal trash service except stray dogs and vultures; there was a 5-peso fine for harming a vulture.2, 8-10 Chickens lived in the hotel kitchens, and the open-air food market had no fly screening, no working drains, and no inspections. Unsurprisingly, the civilian death rate was 50/1000/year.2 Tuberculosis was common, and the military doctors took care selecting buildings to quarter troops. With the hot season coming soon, bringing malaria and potentially yellow fever, quick sanitary work was needed. The Army established a medical structure: COL Henry Birmingham was double-hatted as Chief Surgeon of the Expeditionary Force and Chief Sanitary Officer for the Military Government. (Birmingham had had several years’ experience of managing healthcare for troops mobilsed in Texas, the closest analog the Army had to Veracruz in climate and number of troops.) Each military service had a hospital, the Army had the 216-bed Field Hospital No.3 in the most appropriate building in the city, the Marines an improvised hospital in a small schoolhouse when Solace was not on station. The Public Health Service was brought in to continue maritime quarantine; Army doctors were detailed for public health work but assigned to the Department of Public Works since that was where the labour force was. Field Hospital No.3 (normally an extremely austere organisation mainly for 3-day holding) was augmented with a laboratory, an X-ray machine, beds rather than sacks for straw, and various other low-mobility items. A proper operating room was established, and a dental clinic. The Army sent 12 nurses, their first operational deployment close to a potential frontline, but there are no details on their duties other than general hospital nursing. A special field uniform had to be devised, blue-grey material with white collars, cuffs, aprons, and caps. Given the possibility of fighting, a horse-drawn provisional ambulance company was organised, and field equipment retained when garrison equipment arrived. A small medical supply team (one doctor and five enlisted men) deployed, and ultimately supplied both Army and Navy medical facilities.

For the military force, malaria prophylaxis was enforced; 3 grains of quinine sulfate/man/day and 6 grains for those quartered near the most malarious districts. Fly screens were installed in military quarters, toilets, kitchens, and messes. Manure and garbage were hauled to the city dump for incineration. Troops drank city water, but it was regularly checked; a chlorination system was installed in case but was never necessary.9 Troops were ordered to shower regularly to reduce the incidence of skin diseases. Local vegetables had to be cooked, and canned goods and meat hashes to thrown away if they went unrefrigerated overnight. Surgeons were to make sure there were no mosquito-breeding areas around barracks. Various medical indicia (e.g. fever of 101˚º with albuminuria) were listed as friendly forces information requirements.

Sanitary work was urgent, and done urgently: in early May half the Expeditionary Force and thousands of Mexicans were sweeping the streets, burning trash and garbage, draining water, installing bug screens, and performing other preventive medicine tasks. (Ashes from the burned trash, plus clinker from the coal-fired naval vessels, became filler for potholes and swampy areas and an all-weather road to the dump.) Malaria patients were hospitalised, then sent home with two months of quinine to prevent relapses and the spreading of infection. 1,000 garbage cans were provided city-wide with the city emptying them thrice daily and hauling waste to the dump rather than requiring citizens to do it themselves; compliance rose, and the cans themselves were cleaned regularly.

Image 3: US troops burning trash. Image courtesy Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2001.M.20).

To reduce the disease threat the military forces faced, the Army took strong public health steps. Veracruz was in the throes of a smallpox epidemic when the Americans landed; teams went house-to-house and performed over 46,000 vaccinations. In 1906 by a vigorous Mexican official had started anti-mosquito ditches but they were subsequently neglected. The Army cleaned and repaired existing ditches, while 61 miles of new ditches were dug and house-by-house inspections were performed to look for standing water as the US revitalised and extended the work.11 Sixty-nine thousand gallons of oil were sprayed on standing water. The food market was cleaned, with cracked flooring replaced and screens (augmented with flypaper) issued; the building was hosed out with seawater daily. Vendors who ignored sanitary regulations were warned, then fined, and ultimately imprisoned. For TB control, an ordnance banned spitting, but it could never be as thoroughly enforced. Sanitary inspectors fanned out across the city, dusting off existing laws. Thus, for instance, sanitation plans were required to obtain building permits. A Navy doctor was assigned for general oversight of city hospitals, later an Army reserve doctor who lived in Mexico and was fluent in Spanish. US government civilian sanitation experts from the Panama Canal Zone (which would open during the occupation of Veracruz) arrived to supervise various steps within their recent expertise. Given the Mexican law against collaboration by government employees, US officials ordered some of them to perform their duties, which may or may not have protected them from reprisal.

Money found in the city coffers was spent on public health, and money was borrowed against accounts of the State of Veracruz Llave, but the US Congress also appropriated $40,000 for the work.12 For the long term, public hospitals were cleaned and repaired, and tentative plans were made to open a hospital-based nursing school (as was then the standard in the US) if the occupation lasted longer. The city became sufficiently clean that the vultures left.

Venereal disease was a huge problem. Veracruz was Mexico’s main port and half the businesses were cantinas or brothels, or both.2 The Army controlled the Board of Health, the Police Department, and the Women’s Hospital and could make some headway. The government tried to channel prostitution to the legal ‘red light’ district for better enforcement of laws about bi-weekly inspection of prostitutes. Inspections found 25% of registered prostitutes infected against 90% of “clandestinas.” Infected prostitutes were treated at a “lock” hospital, with up to 125 patients at one time. The Army also inspected the premises and forced unsanitary ones to clean up or close.2 Prophylactics, with instructions in Spanish and English, were made freely available at “registered resorts.” The Army expelled foreign-born prostitutes from the city effective 1 July, although some obtained pro-forma marriages with Mexican men. Salvarsan (arsphenamine) was available to treat US personnel, and the field laboratory at the Army hospital performed all STD tests, military and civilian. (The Army used its medical laboratory not only for military government work, for instance confirmation of malaria cases and inspection of prostitutes, but also made it available to local physicians for their patients.) US officers were forbidden to enter brothels or even visit the red-light district in uniform.3 These measures did not stop STDs; the annual infection rate for US personnel was 359.70/1000/year.

NGOs

From 23 April to 2 September the American Red Cross (ARC) conducted relief work in Veracruz; Admiral Fletcher (commander of the blockading squadron) asked for an experienced relief agent on 29 April.13 It limited its work to ameliorating the “suffering due either directly or indirectly to the American occupation.” This included helping released political prisoners and families of Mexican soldiers but also those who the US occupation put out of business, such as lottery ticket vendors when Funston banned that amusement. Food, money, or medical care was provided, when need was verified. Transportation

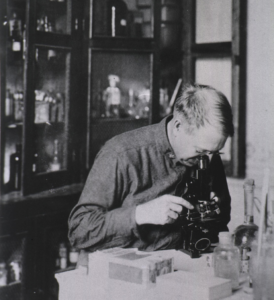

Image 4: Laboratory of Field Hospital No.3, with MAJ Frederick Russell, developer of the typhoid vaccine, at work. Courtesy National Library of Medicine.

was provided both for foreign refugees who needed to return home and getting Mexicans out of Veracruz when they could persuade the ARC that they would be able to support themselves elsewhere. (This could include returning them to their families.) A clinic treated around 6,000 patients. The ARC helped people find work, including labour for the military government. The ARC also helped American refugees leave other ports on the Gulf Coast, where American warships could have inflamed the situation. The ARC provided public health nursing services to the occupation government for an anti-tuberculosis campaign; Mexican civilian nurses were hired to visit homes, presumably getting a better response than US military personnel or Army Nurse Corps (Female) personnel. The Army asked the ARC to run a TB hospital, but the ARC could not secure adequate funds. The Mexican Neutral White Cross, established because the Mexican Red Cross was under government control and would not treat anyone who opposed the government, also operated a medical facility, but no details are available.

Health Outcomes

There were no significant differences between Navy Department and War Department health data, nor between Veracruz and garrisons in the US.14 Malaria and the venereal diseases were the largest problems, followed by diarrhoea and enteritis.15 Sanitation worked: there was a higher incidence of “alcoholism and its results” (29.56/1000/year) than of dysentery (23.31/1000/year). The admission rate was 945/1000/year, with 862/1000 being disease and 83 injury. However, acuity was low with days hospitalised 7.32/soldier and a daily census of 20 – one quarter of whom were VD patients. Deaths (after the fighting) were only 14, seven disease and seven injuries. The death rate for the local population fell from 45.59/1000 (January-May) to 30.59 (June-October). Malaria deaths were only 2/month, even in the summer heat.9,12 But there was negligible long-term impact: by June 1915 “the streets were filthy, with garbage very much in evidence, decaying on the streets and attracting myriads of flies and other insects” and there was another smallpox outbreak, presumably among refugees.16 The vultures literally returned.

Image 5: Vultures at the meat market, Veracruz. Image courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

Lessons

The occupation ended in November 1914. Huerta had actually fallen in July, but negotiating how the US would withdraw took time. The doctors hoped the sanitation measures would survive, and both line and medical officers hoped that the Mexicans who had worked with them would not be persecuted by the new regime. The War Department pressed the State Department and President Wilson to negotiate guarantees for those individuals, but ultimately Wilson accepted the pledge of Presidente Venustiano Carranza, who was unable to exercise his will in Veracruz.

There were some mild administrative problems with a joint occupation, but nothing more than extra paperwork.14,17 For instance, when the Army provided the Navy medical supplies extra receipts were necessary since a Navy appropriation had to be debited and an Army one credited. Navy Department patients required Navy and Army forms to be completed; the Marines’ Navy doctor reported to both the USMC commander on the ground and COL Birmingham as force surgeon. The Army could not pay for Navy hospital laundry. These lessons were minor. Similarly, the Army learned that the standard monthly health report was not sufficiently frequent and adopted weekly reports.18

The services learned that standardised supplies and equipment made field operations easier. The Marines learned they needed battalion and regimental support structures that could support split-base operations.19 The Solace’s problems showed the need for newer, ideally purpose-built, hospital ships.4,19 The Army learned a passive lesson, that in static situations medical units will accrete extra equipment to raise the standard of care. However, the Army had much experience of medical support in tropical environments (Cuba 1898 and 1906, Philippine Islands and Puerto Rico 1898-onwards, Panama 1905-onwards) and the Veracruz experience taught little except to reiterate how hard it was to make cultural changes. The Army would soon have more field experience chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico,20 and the two services would have more joint experience in World War I, when the 2d Infantry Division had one Army and one Marine infantry brigade.21

Birmingham was effective in his dual roles as chief surgeon and chief sanitary officer. To bring about medical changes, the medical adviser had to be credible with his commander. Funston listened to Birmingham, and Birmingham worked through the non-medical Department of Public Works and the Police Department. Birmingham also handled the joint situation with tact; he did not try to micromanage medical support to the Marines, and he handled the presence (or absence) of the Solace without problems. He used the American Red Cross (and apparently the Mexican Neutral White Cross) as effective force multipliers. We should remember Zuiderveld, Elliott, and Langhorne for their courage in treating their comrades under fire (for which they received Medals of Honor), and we should remember the other purpose of military medical departments, of providing a commander with a medically-ready force. Birmingham did that, and managed to do so for an ad hoc mission which changed from a brief intervention to an open-ended occupation.

In the larger picture, the doctors at Veracruz certainly kept their force healthy, but they had no lasting impact on the community. They only sought to make the city medically safe for their own forces, and did not try to change local ways. Enforcing local laws, rather than dictating new ones, was culturally sensitive, but the necessity for the laws had not percolated from the Mexican governing elites to the populace. There was no formal doctrine on using medicine as ‘soft power’ to win support, and, moreover, the entire operation was aimed at Mexico’s political elites and not the populace so there was no intent to win grassroots support. Yet medical officers of the period understood that public health was a way to win support. The US had organised a health department in Cuba in 1900, and had used well-drilling and sanitation as ways to improve living conditions for Filipino villagers to reduce opposition there. They also had experience with local populations not adapting to ‘advanced’ ways: Cuba did not maintain its sanitation efforts after US withdrawal, and the second US occupation (1906-09) had to make further changes in Cuban law, including taxation, to embed the changes.22 Then, as now, it is harder to make a systemic difference, as shown by uneven results from repeated efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Corresponding author: Sanders Marble, william.s.marble.civ@mail.mil

Author Affiliations: US Army Office of Medical History