Abstract

Importance: Since 2001, 3.5 million United States service members deployed overseas in support of the post-9/11 Global War on Terror. While healthy and fit upon deployment, veterans have experienced many complex and often unexplainable illnesses and chronic diseases, with more than 520 000 being diagnosed with cancer. With the implementation of the VA MISSION and PACT Acts, post-911 veterans are increasingly being seen in non-VHA healthcare facilities by non-physician providers.

Objective: To assess the readiness of registered and advanced practice nurses to provide knowledgeable and competent healthcare for post-9/11 veterans in the civilian healthcare system.

Design, setting and participants: A web-based survey was administered by the HunterSeven Foundation (a Veteran-founded non-profit organisation), with 541 nurse respondents.

Primary outcomes and measures: Questions were designed to assess military knowledge, comfort level caring for veterans, self-reported proficiency and prior training of participants. Mean differences were compared using a restricted maximum likelihood, fixed-effects model, with incidence between groups estimated as log-binomial relative risks.

Results: Meaningful gaps in clinical knowledge of screening for and treatment of medically related conditions were identified. Our assessment also highlighted a sparseness of knowledge for making care recommendations based on apposite resources.

Conclusions and relevance: Cognitive biases among healthcare providers in the civilian sector may lead to missed and/or delayed diagnoses, therefore emphasising the need for additional training focused on caring for post-9/11 veterans.

Keywords: Civilian healthcare setting; global war on terror; knowledge and readiness; veterans

Key points

Question: Are civilian (non-VHA) nurses competent and knowledgeable to provide healthcare to post-9/11 military veterans?

Findings: Results from our survey of 541 respondents suggest that many nurses employed in the civilian setting do not have ideal knowledge and understanding of post-9/11 military veteran-related risk factors and healthcare concerns. However, nurse respondents with a history of military service were significantly more familiar with the five key areas of military knowledge (i.e., war-reported illness, traumatic brain injury, psychological impact, military veteran culture, and resources available) than non-veteran nurse respondents. This difference was also true for surface-level knowledge of mental health concerns, combat exposures, healthcare use, demographics and medical outcomes. Having a post-baccalaureate degree did not correspond to greater military knowledge.

Meaning: Non-VHA nurses may benefit from additional training focused on the needs of post-9/11 veterans receiving care in the civilian healthcare setting.

Introduction

Background

The United States has deployed over three million uniformed service members to areas in the Middle East and Southwest Asia in support of the Global War on Terror since the turn of the 21st century.1 While research is limited and preliminary, the data suggests that veterans who have deployed to Iraq and/or Afghanistan are more likely to experience chronic physical symptoms, increased shortness of breath and a decreased level of physical fitness post-deployment compared with pre-deployment.2-4 Prior data extracted from medical records suggests that the same population is experiencing chronic, complex, terminal and otherwise unexplainable medical issues. This includes rare forms of cancer occurring at increased rates than their non-veteran, civilian counterparts with similar demographics.5

Most of the literature surrounding post-9/11 service members focuses mainly on mental health, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidality. Few studies addressed the relationship between non-VHA healthcare providers, specifically those in the nursing profession, and care provided to veterans. A 2015 Congressional Appropriations Committee report suggests that 26% of post-9/11 veterans were enrolled in and received care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). This led researchers and committee members to believe that the remaining use civilian-based (non-VHA) medical facilities.6 While it is assumed that healthcare providers who work in a military or VHA setting offer culturally competent care to veterans, it is important to examine the level of cultural competence among non-VHA healthcare providers.7,8

The information available on this topic highlights an increasing gap of concern, considering post-9/11 veterans account for approximately 19% of the total veteran population. According to projections provided by the Joint Economics Committee, this number is expected to increase to 32% by the year 2034.9,10 As part of the HunterSeven Foundation’s Military Exposures Education and Awareness initiative, this manuscript aims to describe the level of knowledge, beliefs and perceptions among civilian nurses in providing care to post-911 veterans. An important premise is that registered and advanced practice nurses should have basic knowledge about military culture, military experiences and the possible health-related consequences of service to provide adequate and competent care to veterans in a non-VHA setting.

Current knowledge

Post-9/11 veterans are defined as those who have served in the US military (Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force) and have been deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria or Kuwait on or after September 11, 2001 (including Operation Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, Inherent Resolve, New Dawn and Resolute Support).11 Although young (~35 years in age), these veterans encountered high-risk, diverse experiences and may manifest unusual health outcomes as a result.5,12 Respiratory disorders, eosinophilic lung disease, asthma and an array of presumptive conditions, including rare forms of malignancies, began to appear in the months and years following deployments to Southwest Asia.13

Unique healthcare needs of post-9/11 veterans

Mental health

Many veterans of the post-9/11 cohort were exposed to improvised explosive devices (IED) and blasts consequent to serving in and travelling through active war zones.14 In addition, there has been a sizeable uptick in claims for mental health conditions, although many cases go undetected until veterans experience other life crises. While the mental health burden experienced by post-9/11 veterans is well recognised, it has not been acknowledged as a potential barrier to accessing care for other health concerns.

Primary cancer diagnoses in post-9/11 active-duty service members

A twenty-year review of the primary diagnosis of cancers in active-duty service members by the Department of Defense (2001–2021) found that those who served on active duty were more likely to be diagnosed with malignancies than civilians. This determination was made by comparing the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program’s reporting of cancer diagnoses in the US population by year (age-adjusted) with the Department of Defense Military Health System Data Repository cancer diagnoses.15,16 Rates of the most commonly diagnosed cancers (i.e., prostate, lung, colorectal, bladder cancers and melanoma) are 1.4% higher among veterans than civilians.17 Furthermore, post-9/11 veterans averaged 5.2 cases of brain cancer (mostly glioblastomas) per 100 000 per year from 2015 to 2019 among those aged 30–39. In an article published on Military.com, data from the VA and NIH suggests glioblastomas occur at a rate 26% higher in the post-9/11 veteran cohort in comparison to the US non-veteran population.18

Military hazards and potential exposures can vary depending on geographical location, service members’ role and assigned duties.5 Several factors may affect the development of health problems after leaving military service. Hazards may depend on jobs performed, exposure to military-grade fuel, airborne emissions from mechanical equipment, geographical air pollution and high levels of particulate matter in their location of deployment (e.g., Afghanistan and Iraq).5,13 Reported exposures among post-9/11 veterans included combat-related smoke, burn pits (i.e., medical and human waste, tires/rubber, plastics, toxic chemicals, benzene-based jet fuel propellant and general refuse/debris), geologic dust, IED, asbestos and depleted uranium. Vaporised depleted uranium-contaminated dust and soil create a long-term health risk owing to the long half-life of this radioactive, cancer-causing element. Over 85% of those deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan had burn pit contact.19

Ninety per cent of those deployed reported post-deployment exposure-related health concerns. The majority of post-9/11 veterans receiving care at the VHA since 2002 have been seen for various medical concerns (e.g., endocrine, nutritional, metabolic, digestive, respiratory and ill-defined conditions).5 The healthcare needs resulting from military service place these veterans at an increased risk for health conditions compared with civilians.

Post-9/11 veterans who were exposed to airborne toxins during their deployment frequently reported an increase in respiratory-related symptoms and a decrease in physical fitness status.4 The hazards exceeded safe exposure guidelines which coincide with deployment periods.4 Overall, participants were young and did not fall into the demographic of those experiencing specific adverse health conditions (i.e., those with chronic or terminal illnesses that are more commonly seen in the older general population versus a previously healthy and fit military cohort). These findings highlight the importance of a nurse’s role in healthcare, specifically in patient assessment, education, navigation and advocacy.4 With cancers being more prevalent in veterans, mental health concerns and other comorbidities can present as challenges that may interfere with cancer identification and treatment.20

Veteran healthcare use

In August 2014, the US Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (VACAA) in response to the VHA’s inability to provide timely access to healthcare for veterans and their families. The passing of VACAA established the Veterans Choice Program (VCP) that covers veterans seeking treatment at non-VHA facilities.21 The recently passed PACT Act in 2022 provides additional coverage for veterans with an expanded list of presumptive health conditions and specifically addresses health-related military exposures.13

With the increasing use of community healthcare options, most post-9/11 veterans do not seek medical care or are followed by a provider at the VHA.22 Knowledge and competency differences between nurses practicing in non-VHA (versus VHA) healthcare facilities are a growing concern and reflect the readiness to provide effective care for this at-risk group.

Civilian nursing knowledge and understanding of veteran healthcare

Timely and cost-effective healthcare services are critical; however, an understanding of military culture by non-VHA community healthcare providers is essential to prevent poor health outcomes and delayed diagnoses. A recent study assessed how nurses’ awareness of veteran healthcare needs affects the assessment, planning, interventions and evaluation of outcomes in this veteran cohort.8 Nurses typically learn about cultural norms, beliefs and values of specific populations as a component of nursing curriculums. However, those providing care for veterans may benefit from additional training to understand how veterans’ individualised experiences influence health needs. Another benefit is gaining perspective on veterans’ healthcare in the context of military culture.

Often, military culture has been overlooked, misunderstood and insufficiently addressed by non-VHA nurses 8 Twelve per cent of non-VHA nurses reported collecting patient military history or related health information. In contrast, 80% of non-VHA nurses reported they were ‘completely unfamiliar’ or ‘a little bit unfamiliar’ with support services available to veterans. Additionally, 70% of non-VHA nurses do not inquire about military or veteran status when completing an assessment. Less than 4% of non-VHA nurses within this study understood military culture, and few reported having a military service background.8

Veteran reliance on care from non-VHA facilities will increase over the next two decades. Frequently, nurses are the first point of contact for patients receiving care (e.g., initial encounters, assessments and subsequent interactions), therefore, it is instrumental that concerns regarding barriers to care be addressed. This highlights the need for policymakers and key stakeholders to implement guidelines for non-VHA providers to deliver culturally competent healthcare services. Appropriate guidance and training are key priorities for nursing professionals; however, clarity regarding when and where guidance should be offered is needed.23

Materials and methods

Instrument

A Qualtrics, online survey in English was administered to participants. The instrument was adapted from the validated RAND Corporation’s ‘Ready or Not’ web-based tool and followed SQUIRE 2.0 standard guidelines.24 Questions were designed to assess military knowledge, comfort level caring for veterans, self-reported proficiency, and prior training of participants (Appendix A). Before use, subject matter experts in the field reviewed the questions, including nursing professionals, military medical providers and service members. Modifications of the survey were based on a thorough literature review, and changes to the wording were suggested to improve readability. Approval was granted by the HunterSeven Foundation Ethics Review Committee (#HS-0231Z) and the Rhode Island College Institutional Review Board (#2122-2247). The HunterSeven Foundation (a veteran-founded non-profit organisation) distributed the survey, and participation access was open for one month in 2021.

Like the RAND Corporation survey instrument, categorical responses were ranked using a psychometric, 5-point Likert scale for two sections of questions. For Q10.1 through Q10.5, respondents were asked to rate their level of familiarity regarding five specific topics (e.g., war-related illnesses, traumatic brain injuries, psychological impacts of war, military/veteran culture and military/veteran resources) in relation to providing care for post-9/11 veterans, with response options ranging from 1 = completely unfamiliar to 5 = extremely familiar. For Q13, respondents were asked to rate their comfort level for competently caring for post-9/11 veterans, with response options ranging from 1 = extremely uncomfortable to 5 = extremely comfortable.

Participants were also asked a series of dichotomous (true/false) questions (Q11.1 through Q11.7) derived from findings in the literature review pertaining to their surface-level knowledge of post-9/11 veterans, including mental health concerns, combat exposures, healthcare use, demographics and medical outcomes. These were posed as statements requesting participants to decide the accuracy of the response options. This was the preferred method to gain insight into respondent knowledge. That is, providing a close approximation of inferred mastery using either informed reasoning based on statement attractiveness or informed reasoning with endorsement bias.25 The definitive knowledge items were Q11.1, Q11.2, Q11.3, Q11.4 and Q11.7, with the first four questions being reverse coded. Two true/false items (Q11.5 and Q11.6) were included as distractor questions without a definitive answer. These questions were included to identify respondents without thorough knowledge of the survey subject matter, under the presumption that the average true/false response would be 50%.

A second set of dichotomous questions (Q12.1 through Q12.5) were related to the respondent’s practice assumptions and self-awareness. In particular, the nurses were queried about their beliefs regarding veteran suicidal thoughts, status changes, psychosomatic symptoms (mental) and physical fitness / overall health. They were also asked about their physical safety when caring for veterans.

In the final survey question (Q14), nurse respondents were asked for their professional opinion based on clinical experience regarding the average age range of the general non-veteran patient population they observe and diagnose with cancer.

Participants

Participants were identified and recruited through professional organisations and social media using a point of reference sample. Registered nurses and mid-level providers employed either full or part-time in non-VHA healthcare practices in the United States (e.g., emergent, urgent, ambulatory care and inpatient specialty departments) were included. For administrative reasons, agency, travel and telehealth nurses were excluded. Age group, gender, level of education, practice location (state) and military service history were collected as non-identifiable, anonymous information in compliance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). No participation incentive was offered.

State-level data

State-level population data from 2021 were tabulated because variations may affect veterans’ healthcare needs and how they receive care.26 This included the percentage of registered nurses and post-9/11 veterans, as well as the number of VA medical centres per state. Data from states with the most survey respondents were presented to contrast with population-based data. Average responses for Q10 and Q13 and percentages for Q9 and Q11 were included in the table.

Data collection, missing values and statistical analysis

Questionnaire information was converted into numerical identifiers and entered in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS Version 26.0.1.1 (IBM, Armonk, NY) for analysis. Transformations were applied to the data when appropriate to better accommodate statistical applications. This involved 1) rank-linearising the observations from high to low, 2) right-shifting the results by their least upper bound, and 3) variance stabilising the elements, such that their variability is minimally related to their mean value.

Few observations had missing data (<0.5). An examination of the missing data patterns suggested that the unknown values were not randomly aligned, with unequal spacing between the clusters.27,28 Accordingly, listwise deletion, which requires the missing data to be missing completely at random (MCAR), was not used when analysing the data.29

A multistage, expectation-minimisation (EM) algorithm was implemented to accommodate missing values. This entailed finding maximum ‘a posterior’ estimates of model parameters for the set of transformed values for the unobserved latent variables.30 Euclidean distances between the ‘a posterior’ and maximum-likelihood estimates for the respective levels of a variable were computed. The distances were used to partition missing values into their optimal completion categories, akin to a Boolean similarity measure.31 Different approaches for accommodating binary and Likert-scaled data tend to yield comparable results when the percentage of missing data is low.32,33

Descriptive characteristics were tabulated to determine variable cell frequencies, with differences between male and female respondents assessed using Fisher’s exact test. For variables with more than five levels, p-values were computed by Monte Carlo simulation. The sampling frame consisted of 1 000 000 randomly drawn tables in proportion to their hypergeometric probabilities, conditional on the marginal frequencies (i.e., the same total sample size and row/column totals as the observed table).34

Cronbach’s alpha was used to determine instrument consistency in subjective responses. In contrast to the Kruder-Richardson (KR) score that can only be computed for dichotomous survey items, the Cronbach’s alpha score may be computed for dichotomous and multi-level Likert data to determine internal consistency.35 A Cronbach’s alpha score ≥ 0.70 is generally considered an adequate score for a survey tool, consistent with the criterion of Nunally.36 However, this score is not a measure of dimensionality nor a test of one-dimensionality (i.e., one latent variable). An exploratory factor analysis was used to address this question, examining the diminishing total variance explained by each component eigenvalue.37

Mean differences for participants with a history of military service versus those without, as well as participants with a post-baccalaureate degree (master and/or doctorate) versus those without, were compared using a restricted maximum likelihood, fixed-effects model, controlling for age group and sex. Fixed-effects estimates are robust for detecting mean differences between two groups, providing that the samples are reasonably large and have few extreme outliers (i.e., finite variances).38,39

Adjusted relative risk (RR) was used to compare incidence between groups and computed with a log-binomial model.40,41 P-values were estimated using the likelihood ratio test and denoted at ‘PLRT’. Similarly, significance levels corresponding to the additive interaction between groups (RR1/RR2) were denoted as PINT. Akaike’s Information Criteria evaluated goodness-of-fit and case-wise diagnostic statistics, generalised to log-binomial regression.42

Unless indicated otherwise, p-values less than 0.05 indicated a significant association. Rounding was based upon significant figures rather than fixed decimal places (Goldilocks method).43

Results

Demographics

A total of 541 eligible participants completed the survey. They varied by practice state, setting, age range, military service history and level of education (Table 1). Thirty-five per cent of participants were aged 20–29 years and 49% were aged 30 to 39 years. The majority (83%) of nurses indicated practicing in a hospital setting (emergency department, inpatient care and intensive care/critical care), with the remaining respondents practicing in management, primary care, mental health, oncology and surgical settings. Ninety per cent reported working full-time (32 hours or more weekly).

Table 1. Respondent characteristics by sex (N = 541)†

| Respondent characteristic |

Male n (%) |

Female n (%) |

P-value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 78 | 463 | — |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20-29 | 25 (32) | 163 (35) | 0.93 |

| 30-39 | 41 (53) | 224 (48) | |

| 40-49 | 10 (13) | 60 (13) | |

| ≥50 | 2 (3) | 16 (3) | |

| Employment status (per week) | |||

| Full time (≥32 hours) | 74 (95) | 413 (89) | 0.028 |

| Part-time (<32 hours) | 4 (5) | 20 (4) | |

| Per diem | 0 (0) | 30 (6) | |

| Military service | 30 (38) | 34 (7) | <0.0001 |

| Years served in military | |||

| ≤4 | 3 (33) | 18 (33) | 1.0 |

| >4-6 | 3 (33) | 16 (29) | |

| >6-10 | 2 (22) | 14 (25) | |

| >10 | 1 (11) | 7 (13) | |

| Family member served in military | 47 (60) | 285 (62) | 0.90 |

| Highest degree obtained | |||

| Associate | 20 (26) | 85 (18) | 0.34 |

| Bachelor | 52 (67) | 320 (69) | |

| Master | 6 (8) | 50 (11) | |

| Doctorate | 0 (0) | 8 (2) | |

| Practice setting | |||

| Emergency department | 35 (45) | 169 (37) | 0.17 |

| Mental health | 3 (4) | 16 (3) | |

| Acute care (in-patient) | 10 (13) | 112 (24) | |

| Case management | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | |

| Oncology | 1 (1) | 11 (2) | |

| Intensive care | 22 (28) | 99 (21) | |

| Surgical | 5 (6) | 20 (4) | |

| Primary care | 2 (3 | 31 (7) | |

All participants were licensed and actively involved in direct patient care, with 69% having obtained a bachelor’s degree and 11% a post-baccalaureate degree. Participants predominately identified as female (86%). Sixty-four respondents (12%) reported having served in the military, averaging 7.2 years of service (ranging between 2.5–21 years, median = 6 years). Over half (61%) of the participants stated they had an immediate family member who served in the military. Employment status (p = 0.028) and history of military service (p < 0.001) differed by sex.

Frequently occurring health issues

Health issues (Q9) believed to occur among post-9/11 veterans frequently were mental health concerns (e.g., post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and addiction) (92%); medical illness characterised as pulmonary diseases, cancer and autoimmune disorders (7%); and physical injury (e.g., amputations, musculoskeletal injuries, brain injuries) (1%).

Knowledge and preparedness

The items in the ‘knowledge and competencies’ domain (Q10) were internally consistent (standardised Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) and unidimensional, with the first eigenvalue for the reduced correlation matrix of 2.8 being considerably larger than the next value of 0.24. Factor loadings for the first principal component were similar (military veteran culture = 0.50, resources available = 0.48, war-related injury = 0.48, and psychologic impact = 0.46), except for the lower value of 0.29 associated with traumatic brain injury. However, since omitting the latter competency only increased the standardised Cronbach’s alpha by a fractional amount (0.04), we opted to retain all the factors for this domain when presenting our analysis (in line with the original validation of this instrument).

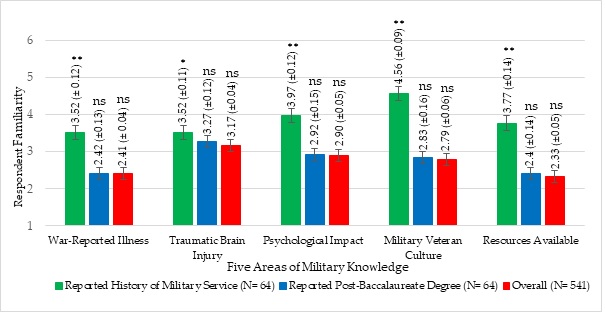

Responses varied on current level of knowledge and preparedness of post-9/11 veterans among respondents that reported being ‘very to extremely familiar’. Approximately 35% indicated traumatic brain injuries (mean = 3.2; SE = 0.04), 28% psychological impacts of war (mean = 2.9; SE = 0.05), 27% military/veteran culture (mean = 2.8; SE = 0.06), 15% military/veteran resources available (mean = 2.3; SE = 0.05), and 12% war-related illnesses (mean = 2.4; SE = 0.04) (Figure 1).

When nurses with a history of military service were compared with nurses without a history of military service significant differences for war-related illness, psychological impacts of war, military and veteran culture, and resources available were observed, independent of age and sex (p <0.001). The effect was less significant for traumatic brain injuries (p = 0.014). It was expected that military veterans would have a higher level of familiarity owing to lived experiences. In contrast, there was no statistically significant difference in all five competencies between nurses who obtained a post-baccalaureate degree(s) and those without a post-baccalaureate degree.

Figure 1. Respondents’ self-reported familiarity with post-9/11 veteran topics.

P-values above indicated bars provide comparisons with respective reference group (e.g., no reported history of military service and no reported post-baccalaureate degree), adjusting for age-group and sex (restricted maximum likelihood, fixed-effects model). Error bars indicate standard error. *p < .05, **p < .001, and ns = not significant.

Surface-level knowledge

The correct answers to the definitive knowledge items were as follows: Q11.1 (FALSE): 7057 have died in combat or from combat-related injuries, while over 5116 have committed suicide while on active duty and over 30 177 have committed suicide following military service;44,45 Q11.2 (FALSE): While many have served in a combat zone, no more than 10% have been engaged in combat;46 Q11.3 (FALSE): As of 2018, only 38.9% of post-9/11 veterans had ever received care within the VA. The majority did not utilise external healthcare in the community;47-50 Q11.4 (FALSE): Approximately 14% of post-9/11 veterans have screened positive for PTSD, whereas ~17% (520 966) have been diagnosed with cancer.51,52 Q11.7 (TRUE): The median age is 38 as of 2022.50,53

More veteran vs non-veterans respondents accurately answered the non-distractor knowledge questions (i.e., age-group adjusted RR > 1.0), except for Q11.1 (Table 2). Significant differences were noted for veterans responding to Q11.3 (male: age-group adjusted RR = 1.9, PLRT = 0.019; female: age-group adjusted RR = 1.4, PLRT = 0.023; combined: age-group and sex adjusted RR = 1.4, PLRT = 0.0015, not shown in table), Q11.4 (combined: unadjusted RR = 2.6, PLRT = 0.027, not shown in table), and Q11.7 (males only: age-group adjusted RR = 1.3, PLRT = 0.022). No significant knowledge differences were observed for respondents with a post-baccalaureate vs no post-baccalaureate degree. All ‘Male x Female’ interactions for veteran and post-baccalaureate degree knowledge questions were insignificant (except for post-baccalaureate degree Q11.4, which was indeterminate).

Table 2. Percentage of respondents accurately answering knowledge questions by sex (N = 541)

| Knowledge question | Profile | Male (n = 78) | Female (n = 463) | PInt | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate Yes | No n (%) |

aRR PLRT |

Accurate Yes | No n (%) |

aRR PLRT |

||||||

| Q11.1† | More post-9/11 veterans have died in combat than by suicide | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 26 (39) | 4 (36) | 0.95 | 23 (6) | 11 (10) | 88 | 0.58 | ||

| No | 41 (61) | 7 (64) | 0.59 | 334 (94) | 95 (90) | 0.26 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 1 (9) | 1.1 | 44 (12) | 14 (13) | 0.95 | 0.17 | ||

| No | 62 (93) | 10 (91) | 0.65 | 313 (88) | 92 (87) | 0.53 | |||

| Q11.2† | Most post-9/11 service members who have deployed have been involved in combat | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 27 (40 | 3 (27)</td | 1.1</td | 26 (8)</td | 8 (6)</td | 1.2</td | 0.74 | ||

| No | 40 (60) | 8 (73) | 0.30 | 301 (92) | 128 (94) | 0.23 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 1 (9) | 0.99 | 40 (12) | 18 (13) | 0.97 | 0.91 | ||

| No | 62 (93) | 10 (91) | 0.96 | 287 (88) | 118 (87) | 0.71 | |||

| Q11.3† | A majority of post-9/11 veterans use the Veterans Affairs hospitals and clinics for most healthcare needs and services | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 26 (46) | 4 (18)</td | 1.3</td | 23 (10)</td | 11 (5)</td | 1.4</td | 0.84 | ||

| No | 30 (54) | 18 (82) | 0.019 | 210 (90) | 219 (95) | 0.023 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 1.3 | 30 (13) | 28 (13) | 0.99 | 0.35 | ||

| No | 50 (89) | 22 (100) | 0.16 | 203 (87) | 202 (88) | 0.96 | |||

| Q11.4† | More post-9/11 veterans have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress than cancer | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 6 (60) | 24 (35)</td | 2.4</td | 2 (10)</td | 32 (7)</td | 1.5</td | 0.63 | ||

| No | 4 (40) | 44 (65) | 0.18 | 19 (90) | 410 (93) | 0.62 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 6 (9) | —* | 2 (10) | 56 (13) | 0.56 | —* | ||

| No | 10 (100) | 62 (91) | 19 (90) | 386 (87) | 0.39 | ||||

| Q11.7 | Most post-9/11 veterans are under the age of 40 years old | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 27 (46) | 3 (16)</td | 1.3</td | 28 (8)</td | 6 (7)</td | 1.1</td | 0.12 | ||

| No | 32 (54) | 16 (84) | 0.022 | 345 (92) | 84 (93) | 0.54 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 5 (8) | 1 (5) | 1.2 | 48 (13) | 10 (11) | 1.1 | 0.15 | ||

| No | 54 (92) | 18 (95) | 0.35 | 325 (87) | 80 (89) | 0.24 | |||

log-binomial regression model). Bac = Baccalaureate. Ind = Indeterminate. Int = Interaction. LRT = Likelihood ratio test.

A composite knowledge score was created by summing the individual definitive knowledge questions. Overall, veteran respondents (mean = 3.3, SE = 0.01) had a significantly higher composite knowledge score than non-veteran respondents (mean = 2.8, SE = 0.04) p = 0.011) (Table 3). Although the mean difference was significant, Cronbach’s alpha value corresponding to the questions in this domain was only 17%, likely reflecting the diffuse nature of the dichotomous items. The composite knowledge score for respondents with a post-baccalaureate degree (mean = 2.9, SE = 0.13) did not significantly differ from those without a post-baccalaureate degree (mean = 2.9, SE = 0.04; p = 0.69).

Table 3. Comparison of respondent composite knowledge scores (N = 541)

| Profile | Composite knowledge‡ Mean ± SE |

P-value† |

|---|---|---|

| Veteran | ||

| Yes | 3.3 ± 0.13 | 0.011 |

| No | 2.8 ± 0.04 | |

| Post-Baccalaureate | ||

| Yes | 2.9 ± 0.13 | 0.69 |

| No | 2.9 ± 0.04 | |

Male vs female veteran respondents were more likely to answer false to distractor question Q11.5, asking if more post-9/11 veterans experienced mental health concerns than Vietnam Veterans (male: aRR = 0.54, PLRT = 0.0036; female: aRR = 0.99, PLRT = 0.95; PINT = 0.018) (Table 4). The other distractor questions for veterans and post-baccalaureate degree holders were not significant, with no interactions being observed by sex.

Table 4. Percentage of respondents responding to distractor knowledge questions by sex (N = 541)

| Distractor knowledge question | Profile | Male (n = 78) | Female (n = 463) | PInt | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response True | False n (%) |

aRR PLRT |

Response True | False n (%) |

aRR PLRT |

||||||

| Q11.5 | Post-9/11 veterans are more likely to experience mental health concerns than Vietnam Veterans | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 12 (27) | 18 (55) | 0.54 | 24 (7) | 10 (7) | 0.99 | 0.018 | ||

| No | 33 (73) | 15 (45) | 0.0036 | 298 (93) | 131 (93) | 0.95 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 3 (7) | 3 (9) | 0.80 | 44 (14) | 14 (10) | 1.1 | 0.40 | ||

| No | 42 (93) | 30 (91) | 0.55 | 278 (86) | 127 (90) | 0.13 | |||

| Q11.6 | Vietnam Veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than post-9/11 veterans | Veteran | |||||||

| Yes | 24 (41) | 6 (30)</td | 1.0</td | 26 (7)</td | 8 (8)</td | 0.98</td | 0.79 | ||

| No | 34 (59) | 14 (70) | 0.88 | 339 (93) | 90 (92) | 0.79 | |||

| Post-Bac | |||||||||

| Yes | 3 (5) | 3 (15) | 0.57 | 40 (11) | 18 (18) | 0.87 | 0.30 | ||

| No | 55 (95) | 17 (85) | 0.11 | 325 (89) | 80 (82) | 0.24 | |||

Int = Interaction. LRT = Likelihood ratio test.

Practice assumptions and self-awareness

Nearly all the respondents (94%) stated they did not feel concerned or worried for their safety when caring for veterans (Q12.1), while almost half (43%) believe most veterans have had thoughts of suicide or are actively suicidal (Q12.2). When the nurses were asked if ‘veteran status’ changes how they provide a patient’s care (Q12.3), 84% stated that status did not impact care processes. Approximately three-quarters (72%) believed that veterans experience psychosomatic symptoms related to mental health concerns (Q12.4). Over half (62%) thought that most veterans returned from combat physically fit and overall healthy (Q12.5). The standardised Cronbach’s alpha score for Q12.1 through Q12.5 was 11%, suggesting only moderate to low consistency for these dichotomously coded items.

Additional questions

Approximately 62% reported feeling either ‘somewhat comfortable to extremely comfortable’ in providing accurate, competent, holistic care to post-9/11 veterans through individualised screenings, assessments, or treatments (Q13). Seventy per cent of respondents reported cancer diagnoses ranging between 50 to 69 years. These findings are slightly less than those reported by the National Cancer Institutes (SEER) Program, citing a median cancer diagnosis of 66 years.16

State-level data

Every state except for West Virginia and Vermont was represented in the survey. California (14%), Massachusetts (6.7%), Texas (6.5%), Florida (5.7%), New York (4.6%), Arizona (3.9%) and North Carolina (3.8%) were the most frequently reported states of practice (Table 5). However, the percentage of survey respondents and the number of VA medical centres per practice state were not uniformly distributed. Similarly, the percentage of respondents in each state and the corresponding percentage of nurses in their respective state of practice differed. California had the greatest percentage of respondents and the highest number of VA medical centres (n = 9) but was home to few post-9/11 veterans (0.83%). On the other hand, only 0.68% of respondents practiced in Massachusetts, yet the state had four VA medical centres. Both Texas (1.2%) and Florida (1.1%) had a reasonable representation of post-9/11 veterans, relative to the number of VA medical centres in each state (7 and 8, respectively).

Table 5. Population statistics and survey responses by primary practice states having the highest percentage of respondents (N = 541)

| Characteristic | Selected Primary Practice State | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ | CA | FL | IL | IN | MA | NC | NY | PA | RI | TX | WA | ||

| Population statistics | |||||||||||||

| % Post-9/11 veterans | 1.1 | 0.83 | 1.1 | 0.82 | 1.1 | 0.68 | 1.3 | 0.61 | 0.90 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | |

| % Registered nurses (RNs) | 2.1 | 9.2 | 6.9 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 0.33 | 2.9 | 0.54 | 1.5 | 0.79 | 2.3 | |

| No. VA medical centers | 3 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 3 | |

| Survey responses | |||||||||||||

| % Respondents | 3.9 | 14 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 3.0 | |

| Q9 | Most frequent issue for post-9/11 Veterans (%)* | ||||||||||||

| 1. Mental health | 90 | 89 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 93 | 91 | 94 | |

| 2. Physical injury | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3. Medical illness | 10 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 6 | |

| Q10 | Self-reported familiarity (Mean)† | ||||||||||||

| 1. War-reported illness | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | |

| 2. Traumatic brain injury | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.0 | |

| 3. Psychological impact | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.4 | |

| 4. Military veteran culture | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.4 | |

| 5. Resources available | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.2 | |

| Q11 | Definitive knowledge questions answered accurately (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1. More post-9/11 veterans have died in combat thanby suicide | 76 | 79 | 88 | 93 | 77 | 86 | 67 | 72 | 78 | 64 | 77 | 69 | |

| 2. Most post-9/11 service members who have deployed have been involved in combat | 52 | 71 | 81 | 80 | 62 | 69 | 81 | 80 | 72 | 79 | 74 | 75 | |

| 3. A majority of post-9/11 veterans use the VA hospital clinics for most health care needs/services | 62 | 56 | 55 | 67 | 46 | 33 | 38 | 56 | 72 | 64 | 40 | 69 | |

| 4. More post-9/11 veterans have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress than cancer | 0 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 0 | |

| 5. Most post-9/11 veterans are under the age of 40 years old | 86 | 76 | 77 | 80 | 69 | 89 | 86 | 88 | 78 | 93 | 77 | 81 | |

| Q13 | I feel competent and comfortable in providing thorough assessments, treatments, and care to post-911 veterans (Mean)‡ |

3.5 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

Mental health (Q9) was the most frequently reported issue for post-9/11 veterans, averaging 94% (SE = 1.5) across the indicated states in Table 5, except for Pennsylvania (83%). Physical injury and medical illness were sparsely reported, with means of 0.83% (SE = 0.53) and 5.5% (SE = 1.3), respectively.

The current level of knowledge and preparedness (Q10) varied across the five domains (war-related illness, traumatic brain injury, psychological impact, military veteran culture and resources available), with Illinois (Mean = 2.9, SE = 0.12) having the highest and Washington (Mean = 2.5, SE = 0.14) the lowest composite, self-reported familiarity scores. Across the indicated states, ‘traumatic brain injury’ had the highest composite score (Mean = 3.1, SE = 0.05), with California (Mean = 3.4 SE = 0.11) having the highest individual score within this domain. In contrast, ‘resources available’ had the lowest composite score across states (Mean = 2.4, SE = 0.06), with Florida (Mean = 2.1, SE = 0.21) having the lowest individual score within this domain.

Illinois had the highest composite mean score of 65% (SE = 15) for correctly answering the five definitive knowledge questions (Q11), compared with Indiana, which had the lowest score (Mean % = 52, SE = 12). Across the indicated states, few participants (Mean % = 5.4, SE = 2.3) were able to correctly answer that more post-9/11 veterans have been diagnosed with cancer than post-traumatic stress disorder (Q11.4). This contrasted with a mean % of 8.2 (SE = 2.0) for correctly answering that more post-9/11 veterans are under the age of 40 years (Q11.7). A mean % score of 55 (SE = 3.7) was observed for affirmatively answering that most post-9/11 veterans use VA hospitals and clinics for most health concerns/services (Q11.3).

Participants practicing in Florida indicated being the most comfortable and competent at diagnosing, treating and caring for post-9/11 veterans (Mean = 4.1, SE = 0.25), while Washington state had the lowest mean score of 3.4 (SE = 0.22).

Discussion

Veterans share a unique culture and common values that influence their behaviour. Even after serving, veterans are still influenced by this culture and values that make it important for healthcare providers to understand so they can better serve this population. It is essential to listen to veteran’s unique stories and avoid making assumptions about their individual experiences. Furthermore, asking questions, showing concern, building trust, understanding trauma and thanking veterans for their service with sincerity are all important considerations when working with veterans in healthcare settings.54

As the care for many post-9/11 veterans has transitioned to the civilian sector in recent years, we expressed concern that registered and advanced practice nurse professionals working outside of the VA system may not be fully prepared to provide knowledgeable and culturally competent healthcare for the distinct needs of post-9/11 veterans.7 A key purpose of the current manuscript was to assess this potential practice gap, with the ultimate goal of improving the quality of health services provided to veterans in this setting.

Our findings suggest that few nurses employed in the civilian, non-VHA setting have ideal knowledge or understanding of post-9/11 military veteran-related risk factors and healthcare concerns. While most non-VHA nurses believe that post-9/11 veterans’ health issues are predominantly related to mental health, post-traumatic stress and suicidality, this precludes attention to other significant health conditions. Survey respondents were divided between whether post-9/11 veterans use the VHA for most of their medical care or if they seek non-VHA care. The majority indicated limited knowledge of resources available to veteran patients in addition to risks of potential war-related illnesses and culture. Interestingly, a greater percentage of veteran respondents answered false to the distractor question Q11.5 (stating that more post-9/11 veterans experience more mental health concerns than Vietnam Veterans), suggesting this to be a potential area needing further research and explanation.

If mental health diagnoses or history of traumatic experiences in post-9/11 veterans leads providers to believe psychological conditions are the most frequently occurring and most expected conditions in practice, this may bias health outcomes. The potential for misdiagnosed or unidentified medical illnesses or malignancies and diagnostic errors with mental health conditions points to provider cognitive biases (i.e., illnesses are mistakenly minimised or ignored because of preconceived notions of prevalent mental health diagnoses in this population). These beliefs may be a result of an unconscious bias towards veterans. Essential ways to address this concern can involve education and training. VHA medical facilities across the US offer healthcare providers training to increase awareness of one’s own unconscious bias towards veterans; however, it is unclear if non-VHA healthcare facilities offer similar training.55

Provider anchoring (aka ‘the anchoring effect’) occurs when the providers’ decision is influenced by a particular reference point or ‘anchor’. In this case, civilian providers may base a diagnosis on an initial impression despite evidence pointing to the contrary. This may lead to a delay in care.56 For example, a post-9/11 veteran who seeks care for persistent shortness of breath and chest pain may be seen as an otherwise healthy, non-smoking individual under the age of 40 with a mental health anchor diagnosis.

Implicit or unconscious bias by providers is another consideration. A norm is to attribute certain qualities to an entire group or cohort that an individual belongs to and is applied widely as a generalisation across individuals within that group.57 In this setting, the assumption is that post-9/11 veterans have related mental health conditions and their assessment, diagnoses and treatment are based on that attribution. Given a lack of preventive screening, inaccurate assessments and a paucity of individualised ‘veteran-focused’ care in non-VHA settings, further evidence-based interventions are warranted to ameliorate the situation.

Knowledgeable frontline nurses are pivotal medical care providers, especially for veterans who are at risk because of their military-related exposures. They have been considered the most trusted profession in the US for the past 20 years based on their honesty and ethical standards, surpassing other providers by ~20%.58 These highly skilled professionals conduct health assessments, gather historical information, coordinate care and interact more with patients in many settings than any other provider or care team member. As the VHA faces budgetary constraints and provider shortages, longer driving distances and wait times will further propel veterans to seek services within their community through the VA MISSION and PACT Acts.

Many VHA facilities across the US are in urban versus rural areas, emphasising that the location of VHA facilities should not be overlooked. This further reinforces the barrier that living in a rural area can place on an individual accessing healthcare. The need for more VHA facilities to adequately meet the needs of post 9/11 veterans, especially in rural areas, is another driving force for veterans to seek care in non-VHA facilities.59 As this priority population grows civilian-based nurses must be appropriately trained in diagnosing and caring for veterans.

Unlike our positive findings for survey respondents who were veterans, there was no significant difference among those with a post-baccalaureate degree(s) versus those without. This highlights that post-baccalaureate degree(s) do not guarantee competence with military-related knowledge and veterans’ healthcare needs, and more appropriate training may be necessary.

The Joining Forces Campaign was created when the Director of the Connecticut VHA teamed up with the American Academy of Nursing and Dr Jill Biden.60 This joint effort requests that non-VHA providers ask patients the fundamental question, ‘Have you ever served in the military?’. The intent is to facilitate communication between patients and providers, to identify risk factors related to veterans’ health and promote individualised medical care. While non-VHA nurses generally wish to attend to the needs of veterans, many feel inadequately prepared and ill-informed to provide appropriate holistic care based on our survey findings. Despite the call for providers to inquire about military service history, many veterans are not being asked about their service-related background in non-VHA care settings.61 Nurses cannot be expected to provide assessments, treatments and care based on information they do not know, so evidence-based, multimodal and interactive training specific to post-9/11 veterans is imperative.

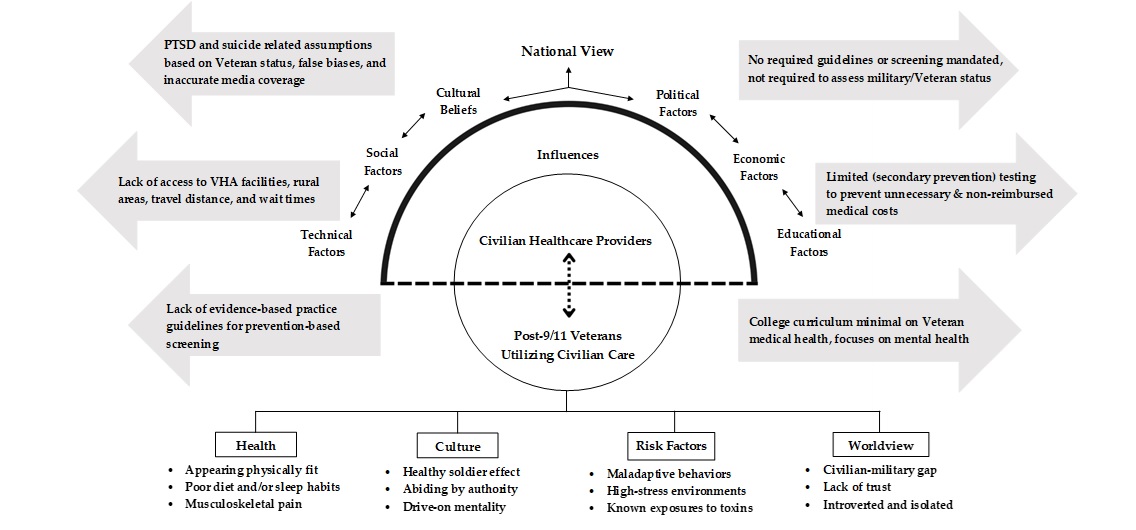

Premised on Leininger’s transcultural model for cultural care, there are six structural dimensional barriers governing the holistic, competent, and individualised care for veterans in the non-VHA setting (i.e., cultural beliefs, technical, social, political, economic and educational factors) (Figure 2).62 Questions in our survey targeted these dimensions to provide ideas for constructive improvements. Cultural beliefs related to ill-informed, inaccurate media coverage and fictional portrayals in films perpetuate stereotypical beliefs about post-9/11 veterans. When asked where post-9/11 veterans receive most of their care, social factors were divided among nurse respondents. While some surmised that most use VHA services, others thought veterans accessed community care.

Figure 2: Adaptation of Leininger’s Sunrise Model

Actionable items and advanced practice population nursing recommendations include:

(a) Enacting an evidence-based curriculum for undergraduate and graduate nursing students and healthcare providers focusing on post-9/11 veteran risk factors and health issues.

(b) Advocating for development and access to cost-free, continuing education credits (CEU) for specified veteran health-related topics and requiring nurses to participate in licensure and renewal.

(c) Forming academic partnerships with the VHA to train students in veteran-centric clinical settings, which can be applied to non-VHA healthcare.

(d) Identifying the most at-risk states (e.g., using data collected on region size, amount of post-9/11 veteran residents, and average distances to VHA and non-VHA medical centres) and enacting guidelines by severity ranking to influence informed policymaking.

(e) Conducting studies involving nurses identifying provider-related factors associated with positive health outcomes in the post-9/11 veteran population.

Limitations

The information provided herein is best interpreted considering several limitations. Surveys are subjective and may not capture the complete picture of a complex topic. Recall, investigator, regional biases and the selectivity of respondents are important factors potentially impacting the validity of this survey. The organisation administering the survey and the intent of the questions asked were not blinded. Internal consistency and unidimensionality were only established for items in the ‘knowledge and competencies’ domain.

Exposures were not uniform during the Global War on Terror, and every veteran has a unique individual health profile related to their location of deployment. Upon return from deployment veterans may be more likely to reside near the base they were deployed from. Battalions and companies from the same states often were deployed to different locations with different inherent health risks. While the analysis lacks granularity, the manuscript is an important first step to more detailed assessments of this topic. We do not believe these limitations influence the conclusions, with most biases towards the null.

Nurse participants completing our survey were not randomly selected and may not necessarily reflect the broader population of nurses working in a particular state. However, given that the survey focused on non-VHA veteran care we anticipated that the percentage of respondents would not reflect the proportion of nurses practicing in their respective states. That is, voluntary response bias could have been present in our sample, given that respondents may have been more likely to practice in non-VHA hospitals that serve veterans. Our survey did not include referent participants practicing in VHA healthcare facilities, thus precluding a comparison with the latter group.

The number of VA medical centres listed in Table 5 by state also did not include community-based outpatient clinics and ‘Vet’ centres. For example, Massachusetts has 14 outpatient clinics and seven Vet centres. While outpatient clinics are not hospitals, like the four other medical centres in Massachusetts, they provide primary and mental healthcare services to veterans. In contrast, Vet centres are non-medical settings that provide no-cost help to veterans and their families. This includes counselling and stress management services for PTSD and military sexual trauma. Excluding outpatient clinics and Vet centres in Table 5 could be considered an undercount of services provided to veterans; however, in this exploratory overview, we wanted to focus on larger-scaled medical facilities that offer a broad range of specialties, including emergency and surgical departments.

Our survey, being conducted by a veteran-run non-profit organisation, was able to engage with participants who otherwise may not have responded to a survey sent from other organisations (i.e., Veterans Affairs or the Department of Defense). While participants may have been more inclined to respond, we cannot rule out conformity bias.

Lastly, the results of this analysis must be carefully interpreted, considering the large number of comparisons and the potential for multiplicity bias.

Conclusions

Nurses are at the forefront of evaluating the specific medical needs of veterans receiving care in the non-VHA/civilian sector, especially in the post-9/11 era. They are well positioned to advocate for interventions and promote positive outcomes for this often-underserved population. The results of our survey indicate that the majority of nurses practicing in non-VHA settings believe that mental health is the most commonly occurring condition among post-9/11 veterans. This potentially neglects attention to other commonly occurring conditions that may present as lifelong challenges to post-9/11 veterans. As seen among veterans from previous wars, it still holds true that veterans’ healthcare needs may peek decades after their deployment and service.63

Demographically, the number of veterans who receive care in non-VHA settings is expected to grow. Nurses must be prepared to provide evidence-based care and demonstrate high levels of knowledge and competency for this at-risk population. As the Post-Deployment Integrated Care Initiative notes, ‘The most important action a provider can take to ensure that a veteran receives optimal care is perhaps the easiest and, ironically, the most neglected: asking if a patient has served in the military and taking a basic military history’.64

While our findings have important implications for nurse training, policy and practice, they also are relevant to physicians and other medical practitioners.

Author contributions: Conceptualisation: CS, JC, LB, JR and SK; survey curation: CS, JC and JR; formal analysis: CS, JR, CJ, KC and JTE; writing, review and editing: CS, JC, LB, JR, PM, CJ, KC, YC, SK and JTE. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. The corresponding author further affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent work.

Funding: None.

Institutional review board statement: Approval was granted by the HunterSeven Foundation Ethics Review Committee (#HS-0231Z) and the Rhode Island College Institutional Review Board (#2122-2247).

Informed consent statement: This project meets exempt human subjects research criteria Category 4, and an informed consent form is not applicable.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their respective institutions or the United States Government.

Data availability statement: Available by request.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Appendix A

Adopted survey instrument

| Question | Choice Selection |

|---|---|

| Q1. Are you trained and licensed as a registered nurse (RN, APRN, FNP, DNP, etc.) | Yes / No |

| Q1a. Do you work directly with, or provide care to patients as part of your regular professional activities? | Yes / No |

| Q1b. Which best describes your highest level of education? |

|

| Q2. Please tell us which best describes your practice setting. |

|

| Q3. Are you employed? |

|

| Q4. Gender at birth: |

|

| Q5. Which state do you currently practice in? | [Free text] |

| Q6. Please select your age range (years): |

|

| Q7. Have you ever served in the United States Armed Forces (this includes the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and National Guards / Reserves) | Yes / No |

| Q7a. If yes, please indicate how long (in years) you served in the military. | [Free text – numerical) |

| Q8. Do you have any close family members who currently or formerly served in the United States Armed Forces? | Yes / No |

| Q9. Based on your experience, what issue do you believe is occurring most frequently in Mental Health the post-9/11 veteran population? |

|

|

Q10. Using the [Likert Scale] please rate your current level of knowledge and preparedness regarding the following topics pertaining to post 9/11 veterans: Q10.1 War-related illness Q10.2 Traumatic brain injury Q10.3 Psychological impacts of war Q10.4 Military and veteran culture Q10.5 Resources available |

|

| Q11. Please select ‘true’ or false’ for each question pertaining to post-9/11 veteran knowledge. | True / False |

| Q11.1 More post-9/11 veterans have died in combat than by suicide. | |

| Q11.2 Most post-9/11 service members who have deployed have been involved in combat. | |

| Q11.3 A majority of post-9/11 veterans use the Veterans Affairs hospitals and clinics for most healthcare needs and services. | |

| Q11.4 More post-9/11 veterans have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress than | |

| Q11.5 Post-9/11 veterans are more likely to experience mental health concerns than Vietnam Veterans. | |

| Q11.6 Vietnam Veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than post-9/11 | |

| Q11.7 Most post-9/11 veterans are under the age of 40 years old. | |

| Q12. Please select “true’ or ‘false’ for each question based on your belieís about post-9/11 True / False veterans. | True / False |

| Q12.1 When caring for veterans. I worry about my physical safety. | |

| Q12.2 The majority of veterans are suicidal and have had thoughts of suicide. | |

| Q12.3 A patient’s veteran status changes how I provide overall care. | |

| Q12.4 1 belleve veterans experience many psychosomatic symptoms related to mental | |

| Q12.5 I believe veterans returning from combat are physically fit and overall healthy. | |

| Q13. I feel competent and comfortable in providing thorough assessments, treatments. and care to post-9/11 veterans. |

|

| Q14. In my opinion and based on my personal clinical experiences, the average age range (years) of patients diagnosed with cancer Is? |

|

Corresponding Author: Kaitlin Jane Cassidy, kaitlin.cassidy@va.gov

Authors: C Simoni2,3, J Costello2,3, L Blanchette3, J Ratliff2,4, P Bith-Melander5, C Jindal6, K J Cassidy1, Y M Choi7, S Kronsteadt2,8, J Efird1,9

Author Affiliations:

1 VA Boston Health Care System Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center

2 HunterSeven Foundation

3 Rhode Island College Zvart Onanian School of Nursing

4 James A Haley Veterans Hospital

5 California State University Stanislaus

6 The University of Sydney School of Medicine

7 Signify Health Inc

8 Baylor College of Medicine

9 Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine