Introduction

The present study aims to investigate how self-esteem and perceptions of self or public stigma may influence a) the attitudes towards seeking professional mental health help in the military environment and b) the intentions to seek professional mental health help. The military is associated with duties of high risks, which often cause exposure to traumatic stimuli.1 Those duties are associated with mental health problems,2 affecting individual’s occupational functioning and organisation’s performance. Although military personnel are at high risk of mental health problems, they do not prefer to seek mental health help due to stigmatising beliefs and fears common among military personnel.3-4

Stigma is the perception that a flaw makes the person unacceptable socially because of psychological or physical characteristics.5 Both self-stigma and public stigma may be related to attitudes or intentions of seeking psychological support, both among civilians and military personnel.6-7 Self-stigma—the perception that an individual’s value diminishes when seeking help from a professional of mental health—relates to seeking psychological help,6-8 and is associated with an individual’s self-esteem and the reconstruction of self-value and personal perception as being socially unacceptable. In addition, self-stigma is associated with social representations of mental illness and psychological support. Social representations of mental illness could reduce an individual’s personal self-image, self-esteem and self-efficacy.6-8 Usually, military personnel form a self-image of power and capacity, and therefore, experiences of symptoms of mental health disorders are perceived as a sign of weakness and are accompanied by shame.7 Public stigma, associated with seeking psychological help, is the perception that the person who seeks psychological support is undesirable or socially unacceptable.6-7 This perception can lead to stereotypes, prejudice and social discrimination against people seeking professional psychological support.6-7

Several studies have analysed the social representation of seeking psychological support in the military. Results indicate that the central core of the social representation for seeking support consists of two categories: a) positive evaluation of psychological support services; and b) results for all three categories of participants: soldiers, military students and officers.8-9 In the same study, stigma appears in the dynamic zone of the representation, which is a common category but less powerful for all three categories of participants. This finding might indicate that stigma is of considerable concern to military personnel.10 The positive evaluation of psychological support services and their effects can be interpreted as recognition of the value of psychological support within the army. At the same time, this finding is in line with another that mediates the correlation between fear of stigma and attitude towards the process.11

According to research, an individual for whom there is information that looks for support and care for depression is considered emotionally unstable, less interesting and less confident than the person who seeks help for back pain.12 Mental health stigma13 appears to be one of the most frequently reported barriers to mental health help-seeking in the military environment.14 Often, seeking psychological support is experienced as inferior or unsuitable,15 so avoidance is inevitable.16-17 Fear of stigmatisation is the most common reason that people avoid seeking mental health help. This fear can be more powerful if people consider how others would react if they knew about their behaviour of help-seeking.18 Corrigan states that people who avoid care from mental health specialists do so to avoid being classified as mentally ill. He also adds that their secondary benefit is to avoid feeling bad about themselves.6

Among other factors, stigma appears to be a central factor due to which military personnel frequently delay disclosing mental health issues and illnesses.19 Military personnel have the belief that others in the military will build a negative impression and stigmatise people who seek professional mental health help. Obstacles can arise for their promotion and career because of this choice, preventing them from going on future deployments.20

Recent research has shown that the military has more positive attitudes about the causes of mental illness but more negative attitudes about the job rights of those with mental illness,21 and that cultural issues interfere with the process of seeking help, the highest scores in the comprehensive stigma perception index appeared for schizophrenia and substance use, and the lowest for anxiety disorders and anorexia.22 In addition, a significant finding is that military personnel may experience even greater public stigma than civilians because their military records are less private because mental health professionals are often employed by the military, and seeking mental health help or enjoying the care of mental health specialists may harm possible job options and promotions.23 Military officials do not seek psychological help even when needed because they believe a) they will be considered weak, b) their superiors will react differently towards them than the rest of the personnel, and c) their colleagues in their unit will trust them less.

Corrigan and his colleagues state that self-stigma affects feelings of self-esteem and self-efficacy, and for that reason, anticipated self-stigma may lead people to avoid seeking help.24 Research has shown that anticipated self-stigma and perceived public stigma have a differential impact on attitudes towards formal and informal help-seeking. The internalisation of negative stereotypes concerning the process of seeking mental help was negatively correlated to the perceived importance of medical providers’ services (general practitioners and psychiatrists).25 Another study in a civilian sample indicated that although both gender and the self-stigma associated with psychological help-seeking predicted attitudes toward seeking psychological help significantly, public stigma was not a significant predictor of help-seeking attitudes.26-30

Military personnel, according to research, believe that seeking mental help would have devastating effects on their military career.27 In contrast, 45% of military personnel believe that military colleagues will avoid anyone seeking professional help.28 Military self-stigma was found to mediate the relationship between military identity components and suicide risk.28 A recent study has shown that there is no evidence of an association between self-stigma and gender, age, sexual trauma or military trauma. In contrast, self-stigma was associated with lower income and higher levels of anxiety, depression and traumatic stress symptoms.29

On the other hand, beliefs in the effectiveness of mental health treatment are positively associated with seeking help.30 The negative effect of the belief that visiting the Psychological Support Office might be a sign of weakness and the doubt about the role of the psychologist and the observance of confidentiality disappears when there is a perception of its usefulness. This means that the recognition of psychological support’s usefulness in the army mediates the correlation between fear of stigma and attitude towards the process of seeking mental help.11

Research questions included the following:

a. We assume that the intention of seeking mental help will be negatively correlated with the perception of self or public stigma coming from this attitude in the military environment (Η1).

b. We assume that a negative attitude towards mental health services will be negatively correlated with the intention of seeking professional help, even if it is needed. Also, we hypothesise that a negative attitude towards psychological support may be positively correlated with the perception of self and public stigma coming from this procedure (Η2).

c. We assume that the intention of seeking mental help will be negatively correlated with the attitude towards professional help in the military environment (Η3).

d. We assume that self-esteem will be positively correlated with a positive attitude towards mental health services and negatively with the perception of self and public stigma coming from the procedure of seeking mental health help (Η4).

e. We hypothesise that high military self-esteem might encourage the belief that military personnel can handle by his own the psychological difficulties and might strengthen a) negative attitudes towards the psychological support in the military, b) beliefs of self-stigma, and c) beliefs of public stigma that might lead to low intentions of seeking professional mental health help (H5).

Method

The research was conducted in military schools in Greece and has received relevant permission from the Greek military authorities, both for the conduct and presentation of the results. This is an anonymous survey in which students of the military academies participated voluntarily. After declaring their consent to participate in the survey, students completed the questionnaires (in print form) in academic education, in the presence of the researcher and without receiving any help or pressure. The researcher collected and stored the data while all data security requirements were met.

Measures

The survey used measured a) attitudes toward help-seeking, b) intention of seeking professional help, c) self-stigma, d) public stigma, and e) self-esteem. The scales used are the following:

a) Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form15 (Cronbach’s alpha.85). This scale consists of 10 items rated on a 4-point bipolar Likert scale, as follows: 0 = Disagree 1 = Partly disagree; 2 = Partly agree; 3 = Agree. The scale assesses individual attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Here are some examples of the items: (1) If I believed I was having a mental breakdown, my first inclination would be to get professional attention.

Items were reversed according to the instructions of the constructors of the scale (e.g. ‘The idea of talking about problems with a psychologist strikes me as a poor way to get rid of emotional conflicts’). Fischer and Farina reported that the shorter scale was equivalent to the longer 29-item scale (correlation of 0.87), had good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84), and test-retest reliability (r = 0.80) over a 4-week interval15. The present study found good internal reliability for Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form (Cronbach’s alpha 0.85).

b) General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ)31 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75). Participants completed the GHSQ. Evaluations of this scale were made on a 7-point scale (1 = Extremely unlikely, 7 = Extremely likely). This scale uses the following standard problem probe, within which targeted problem types can be interchanged: ‘If you were having a personal or emotional problem, how likely is it that you would seek help from the following people?’: (4). mental health specialist. Wilson and his colleagues reported that the GHSQ items had good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85–0.92, test-retest reliability assessed over three weeks)31. In the present study, we found good internal reliability for General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75).

c) Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help with the Self-Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH) scale32) (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83). Participants completed the 10-item SSOSH scale,32 which asked them to rate each item on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely well) on the degree to which it assessed the concept. The items were like the following: (1) I would feel inadequate if I went to a therapist for psychological help. The items were reversed following the author’s instructions (e.g. (2) My self-confidence would NOT be threatened if I sought professional help, (7) I would feel okay about myself if I made the choice to seek professional help). Several studies cross-validated the reliability of the scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 to 0.90; test-retest, 0.72). In the present study, we found good internal reliability for SSOSH scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83).

d) Perceptions of stigmatisation by others for seeking psychological help (PSOSH) scale18 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.82). The 5-item PSOSH was administered to the participants with these instructions: ‘Imagine you had an academic or vocational issue that you could not solve on your own. If you sought counselling services for this issue, to what degree do you believe that the people you interact with would?’ (e.g. (4) Think of you in a less favourable way. Responses to the above items are according to a 5-point Likert scale, as follows: 1: Not at all; 2: A little; 3: Some; 4: A lot; 5: A great deal. Items are summed so that higher scores reflect greater perceptions of stigma by those close to the person seeking psychological help. (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84–0.85 through test-retest reliability assessed over three weeks). In the present study, we found good internal reliability of PSOSH scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.82).

e) Self-Esteem Scale (SES)33 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75). Participants completed the Self-Esteem Scale, a ten-item Likert scale with items answered on a 4-point scale, from 4 strongly agree to 1 strongly disagree. (e.g., (3) I think that I have a number of good qualities). Five items were reversed according to the instructions (e.g. (2) At times, I think I am no good at all). In the present study, we found good internal reliability of the SES (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75).

All scales were administered to participants in Greek after being translated twice by different persons and then combined. The items in Greek were given for back translation to a third person to see if there was anything misunderstood. The relevant handling test was carried out to determine whether the questionnaires work for Greece’s military personnel. The self-esteem questionnaire has been validated for the Greek population,34 as well as the questionnaires for public and self-stigma.35

Table 1. Cronbach’s alphas for all questionnaires

| N | Items | Cronbach’s alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form | 442 | 10 | 0.85 |

| General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) | 442 | 10 | 0.75 |

| Self-Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH) | 442 | 10 | 0.83 |

| Perceptions of stigmatisation by others for seeking psychological help (PSOSH) | 442 | 5 | 0.82 |

| Self-Esteem Scale (SE) | 442 | 10 | 0.75 |

Participants

Students (N=442) from Hellenic Academies from all three armed forces participated in this research anonymously and voluntarily. Sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. Most of the participants (50,7%) were students of Evelpidon Hellenic Military Academy (N=224), (30,8%) were students of Hellenic Naval Academy (N=136) and finally, 81 of them were students of Hellenic Air Force Academy (18,3%). As expected, due to the ratio of admission to military schools, the majority of participants were men (70,4%, Ν=311), and only 47 were women (10,6%). In comparison, a notable percentage of 19% did not mention their gender at all (Ν=84). At the same time, there seems to be an equal distribution of students per year of study, 1st (Ν=91 20.6%), 2nd (Ν=106 19.7%), 3rd (Ν=87 24.2), 4rth (Ν=76 17.2), Missing Value (Ν=82 21.1).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hellenic Military Academy | 224 | 50.7 |

| Naval Academy | 136 | 30.8 |

| Air Force Academy | 81 | 19.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 311 | 70.4 |

| Men | ||

| Female | 47 | 10.6 |

| Missing value | 84 | 19.0 |

| Year of Study | ||

| 1st | 91 | 20.6 |

| 2nd | 106 | 19.7 |

| 3rd | 87 | 24.2 |

| 4th | 76 | 17.2 |

| Missing value | 82 | 21.1 |

Results

Cronbach’s alpha of all the scales used was very good, from 0.75 up to 0.85, as is clearly presented in Table 1. There is no statistically significant interdisciplinary or transgender differentiation to a) the attitude towards the institution of psychological support, b) the intention of seeking psychological support in an emergency, and c) the beliefs about the results of self and public stigma concerning that process.

Descriptive statistics

Results indicated that only a small percentage of the military personnel would seek help from a) a mental help specialist for all three forces, b) telephone consult, or c) a doctor. Even if there were suicidal ideas, attitudes and intentions to seek professional help didn’t change significantly. In addition, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help tend to orient themselves towards the negative pole. Students seem to and present as admirable people who solve their problems independently.

As shown in Table 3, a) attitudes towards seeking mental help have a mean of 1.60 (SD 1.14), b) the mean of self-stigma is 2.99 (SD1.91), c) the mean of public stigma is 2.05 (SD 1.17), and d) the mean of self-esteem is 3.88 (SD 1.81).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

| N | Mean | Median | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attitudes | 442 | 1.69 | 1.8 | 1.14 |

| 2. Self-stigma | 442 | 2.99 | 2.9 | 1.91 |

| 3. Public stigma | 442 | 2.05 | 1.8 | 1.17 |

| 4. Self-esteem | 442 | 3.88 | 3.01 | 1.81 |

Correlation

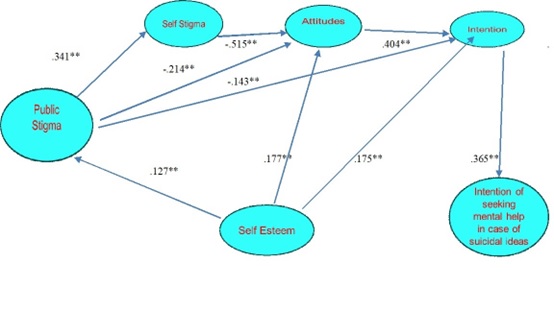

Furthermore, a Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between attitudes towards seeking mental help and perceptions of self-stigma and public stigma. There was a negative correlation between attitudes and self-stigma, r = -0.515, p < 0.001, and attitudes and public stigma, r = -0.214, p < 0.001 (Table 4), which means that as the sense of self-stigma decreases, attitudes towards seeking help become more positive, and vice versa, as the sense of self-stigma increases, the attitudes to seek professional help become more negative. In addition, self-stigma is positively correlated to public stigma (r = -0.341, p < 0.001, which means that as the sense of self-stigma increases, so does the sense of public stigma and vice versa.

Table 4. Correlation of attitudes towards seeking professional mental help with self-stigma, public stigma and self-esteem

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attitudes | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Self-stigma | -0.515** | – | – | – |

| 3. Public stigma | -0.214** | 0.341** | – | – |

| 4. Self-esteem | 0.177** | -0.003 | 0.127** | – |

Moreover, self-esteem is positively correlated to attitudes concerning seeking mental help (r = -0.177, p < 0.001), to public stigma (r = 0.127, p < 0.001) and to the intention of seeking mental help r =.175, p <.001, which means that as the sense of self-esteem increases, attitudes towards seeking mental help become more positive, and vice versa, as the sense of self-esteem decreases, attitudes become more negative. Moreover, when self-esteem increases, public stigma increases as well, as does the intention of seeking mental help. We found that self-esteem is neither positively nor negatively correlated with self-stigma, despite the theory of self-stigma for the general population, according to which beliefs of low self-esteem related to self-stigma concerning seeking psychological support (Table 1). We should investigate this finding further, especially in the military environment and the structure of military personnel’s self-esteem.

In line with the relevant literature, positive attitudes towards seeking mental help are positively correlated to the intention of visiting the Office of Mental Help (r = 0.365, p < 0.001, and even more so when there are suicidal ideas (r = 0.365, p < 0.001 (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Association of public stigma with attitudes towards seeking psychological help, self-stigma, intention to seek mental help, intention to seek mental help in case of suicidal ideas and self-esteem.

Regression analysis

In the case of mediation, high military self-esteem, which reinforces the belief that a military person is capable of doing it on his own, even if there are positive attitudes towards the institution of psychological support in the military, reinforces beliefs of self-stigmatisation and public stigma, and reduces the intention to seek help from a mental health professional. Perceptions of self-esteem are positively related to attitudes towards seeking mental health help (β=0.19). However, negatively related to self-stigmatising beliefs (β=-0.46), and public stigmatisation beliefs about seeking psychological help in case of need (β=-0.25), as clearly presented in Figure 2 and Table 5.

Figure 2. The case of mediation. High self-esteem mediates attitudes, self-stigma and public stigma and diminishes the intention of seeking professional mental help.

Table 5. Regression analyses of variables in intention to seek help from a mental health professional

| B | F | df | sig | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | 0.19 | 19.322 | 1.168 | 0.001 | 0.27 |

| Self-stigma | -0.46 | -45.761 | 1.168 | 0.001 | 0.21 |

| Public stigma | -0.25 | -11.912 | 1.168 | 0.001 | 0.06 |

| Self-esteem | 0.52 | 64.444 | 1.68 | 0.001 | 0.27 |

Discussion

Findings did not reveal any difference between the sexes or the students of all three armed forces regarding the attitudes towards and the intention to seek mental help or perceptions of self and public stigma concerning this process. Results, in line with other research, showing that stigmatising attitudes are prevalent and associated with a reluctance to seek help,36 confirm our hypothesis that self and public stigma are negatively correlated and intentions of seeking professional mental help (H1), (H2), (H3) and positive correlated with the attitudes towards seeking mental help (H4), in line with the theory that social attitudes do not predict behaviours.37

The value that comes from the results is the importance of self-esteem variable. Self-esteem seems to be a more independent characteristic among military personnel. It has a different structure and dynamic not affected by stigma (H4), perhaps because of the military education and the emphasis on power and qualities. Although a lot of research and theory supports stigmatised group members’ tendency to have low global self-esteem, empirical research typically does not support this prediction sometimes in civilians,38 and in the present study among military personnel. Regression analysis has shown that self-esteem mediates beliefs of self and public stigma, as well as attitudes towards seeking professional help when needed. In line with research that highlights the difficulty of knowledgeable individuals who have high self-esteem,39 to change attitudes, it seems that military personnel who build a social identity of strength, high self-confidence and high self-esteem, characteristics that help them build the social identity of the worthy soldier, find it challenging to seek psychological help in difficult times as this would amount to a decline in military virtues. The implications of this result must be examined with new research addressing both civilian and military samples to identify similarities and differences in beliefs, stereotypes, attitudes, intentions and personality characteristics. In the military, stressful conditions trigger the mental vulnerability of individuals, and in combination with the access to weaponry, the need for psychological support is more than necessary.

The role of the family and the social environment should be further examined in supporting military personnel to adjust to stressful conditions. The unit commanders should be trained to encourage military personnel not to avoid psychological help if necessary. Psychoeducation should enrich beliefs and attitudes concerning the protection of privacy, not only concerning the content of the sessions but even concerning the attendance of a mental health specialist. Commanders are responsible for protecting the potential of every military officer to seek mental help, if necessary, without being afraid of being stigmatised and unwanted. It must be clear that only mental health specialists can diagnose and take effective care of a psychological problem. Experienced military personnel can detect behavioural disorders and cooperate with mental health specialists to deal with behavioural problems.23 In addition, subsequent research should check whether the military status of military psychologists negatively mediates the seeking of help from mental health specialists in the military and reinforces the fear of public stigma.

As with all research, there are limitations to this study. First, there was no provision to limit the research to a sample of military personnel experiencing more intense psychological stress or personality disorder. However, we did take a random sample from all military personnel. This poses an additional limitation as if someone does not experience a problem, he/she will not have a positive attitude toward seeking help, especially when there is a risk of public stigma. On the other hand, we had no information about their experience adjusting to the military environment. Perhaps some interviews should bring interesting information about the social and emotional atmosphere. Second, it is true that we haven’t included the health personnel in the participants because health personnel are very small in the military school. Students go to military hospitals if needed. That is a minor limitation to our work because this could numerically balance the number of male and female participants and perhaps affect the statistical analysis. Unfortunately, the staff are a small group of less than 10, who couldn’t have influenced the statistics. Third, our participants were only military students, which limited our work since our results couldn’t be generated for all military personnel. Perhaps future research should include military officers who train military students to compare attitudes and behaviours among military groups.

In summary, the present research focused on the factors that influence the search for mental help in the military, with emphasis on military trainees and found that high morale and high self-esteem, cultivated in the military as qualifications and guarantees for individual and national security, create additional obstacles to the process of seeking psychological help as beliefs of self-stigmatisation and public stigma undermine it.