Commander Neil Westphalen, Royal Australian Navy Reserve

Introduction

This article follows a previous paper by the author regarding occupational and environmental medicine in the ADF.1 The previous paper asserts that high rates of preventable workplace illness and injury indicate the need to improve the management of the occupational and environmental hazards associated with ADF workplaces, with better emphasis on prevention rather than treatment.

The previous article therefore advocates that, rather than attempting to replicate the treatment service paradigm used for Australian civilians, the ADF’s health services should be premised on an occupational and environmental health paradigm. For this to occur, the health capability gaps in the current ADF health service delivery model suggests the need to reassess the fundamental inputs to health capability for both Joint Health Command and Defence’s Work Health and Safety Branch. Such a reassessment could lead to a genuinely holistic and sustainable workforce-based ADF health service delivery model by 2030.

This article expands on the previous paper, with respect to providing primary health care for ADF members.

Primary health care in Australia

In 2014, the Australian health care system had 98,807 medical practitioners in more than 80 specialties, including 32,050 general practitioners.2 The latter included 21,576 Fellows and trainees of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, and 1630 Fellows and trainees of the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine. The remaining 8844 general practitioners did not have fellowships but were vocationally registered by Medicare to provide primary health care services. By comparison, in 2014 the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine represented only 492 Australian physicians and trainees.

Definitions

The definitions of ‘primary health care’ used in Australia are rather complex. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare defines primary health care as ‘typically the first health service visited by patients with a health concern…. It includes most health services not provided by hospitals, and involves:

• A range of activities, such as health promotion, prevention, early intervention, treatment of acute conditions and management of chronic conditions;

• Various health professionals, such as general practitioners, dentists, nurses, Aboriginal health workers, local pharmacists and other allied health professionals; and

• Services delivered in numerous settings, such as general practices, community health centres, allied health practices including physiotherapy and dietetic practices, and more recently via telecommunications technologies such as health advice telephone services, video consultations and remote monitoring of health metrics through electronic devices’.3

The College of Rural and Remote Medicine’s position paper, Defining the specialty of general practice, refers to the 1991 international consensus description of general practice as follows:

‘The general practitioner or family physician is the physician who is primarily responsible for providing comprehensive care to every individual seeking medical care and arranging for other health personnel to provide services when necessary.

The general practitioner/family physician functions as a generalist who accepts everyone seeking care, whereas other health providers limit access to their services on the basis of age, sex or diagnosis. The general practitioner/ family physician cares for the individual in the context of the family, and the family in the context of the community, irrespective of race, religion, culture or social class. He is clinically competent to provide the greater part of their care after taking into account their cultural, socio-economic and psychological background. In addition, he takes personal responsibility for providing comprehensive and continuing care for his patients.

The general practitioner/family physician exercises his/her professional role by providing care, either directly or through the services of others according to their health needs and resources available within the community he/she serves’.4

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ website describes general practice as providing ‘person- centred, continuing, comprehensive and coordinated whole person health care to individuals and families in their communities’.5 It also indicates that, as a relationship-based specialist medical discipline, general practitioner clinicians are defined by the characteristics of their discipline, which are person- centredness; continuity of care; comprehensiveness; whole person care; diagnostic and therapeutic skill; coordination and clinical teamwork; continuing quality improvement; professional, clinical and ethical standards; leadership, advocacy and equity; and continuing evolution of the discipline.

Implications

Some general practice attributes per the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ website in particular, facilitate the baseline clinical skills required to provide primary care for deployed ADF members, and to undertake humanitarian aid / disaster relief operations6. These attributes include providing comprehensive whole-person diagnostic and therapeutic care, within a clinical multi-disciplinary environment (usually but not always in a lead role), to individual patients.

However, the attributes that are less consistent with respect to primary care for ADF members, pertain to person-centredness (particularly with respect to the duty-of-care obligations of their patient’s chain of command), continuity of care (with particular referenceto their patient’s geographic mobility) and (except in very limited circumstances), only providing care for a working-age population that has an increasing but still small proportion of female members

Furthermore, neither the College of Rural and Remote Medicine nor the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners refers to a role for general practitioners with respect to assessing the effects of workplace hazards on their patient’s health or vice versa (that is, assessing their patient’s medical suitability for employment). The author’s earlier paper described some of the limitations of general practitioners regarding their capacity to undertake these tasks.

On the other hand, military and civilian occupational and environmental physicians can complement their general practitioner colleagues regarding the primary care diagnosis and treatment of workplace- related musculoskeletal and mental health disorders, managing workplace-based rehabilitation, and assessing medical suitability for employment and deployment.

ADF non-deployed primary health care

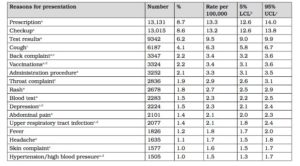

The earlier paper notes that anecdotally, only 20-40 per cent of ADF primary care presentations are for conditions typically seen in an equivalent Australian civilian population. In support of this contention, Table 1 describes the top 30 reasons for civilian patients to see a general practitioner in 2013-14.

Table 1: Top 30 reasons to present to civilian general practitioners, 2013-148

Notes:

- Includes multiple diagnoses.

- LCL=lower confidence level;UCL=upper confidence level.The smaller the interval between LCL and UCL ,the more likely the rate per 100,000 presentations figure is truly representative.

- Most common ADF clinical conditions in 2007-8 and 2008-9.9

- Most common civilian clinical conditions.10

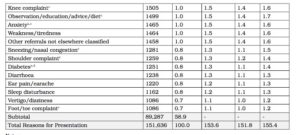

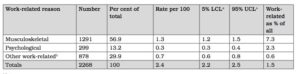

Furthermore, Table 2 shows that in 2013-14, only 2.4 per 100 patient presentations to civilian general practitioners were for work-related reasons, making up only 1.5 per cent of all reasons to see a general practitioner.

Table 2: Most common work-related reasons to present to civilian general practitioners, 2013-1411

Notes:

a. LCL/UCLasforTable1.

b. Includes general check-ups, administrative procedures ,cuts/lacerations, and other skin injuries.

Notwithstanding the lack of data regarding ADF primary care presentations, Tables 1 and 2 confirm the substantial differences between the ADF and civilian populations. In short, compared to their civilian colleagues, ADF general practitioners see proportionally far more musculoskeletal and mental health disorders, most of which are either work-related or affect the ability of the patient to work.

Furthermore, these figures do not include non- primary-care ADF general practitioner presentations such as health assessments (‘medicals’) or Medical Employment Classification Reviews, both of which are occupational and environmental health functions. These presentations arguably consume 30-40 per cent of the average military general practitioner’s workload, or about the same as their actual clinical workload.12

General practitioners and occupational and environmental health

The earlier paper refers to the extensive media commentary that demonstrates the need to improve how the ADF manages occupational and environmental hazards in its base settings. It also noted that thus far there has been no requirement for ‘garrison’ health services to facilitate local Command compliance with the Work Health and Safety Act 2011. This limitation, combined with a lack of occupational and environmental physicians within Joint Health Command, currently restricts ‘garrison’ rehabilitation and other clinical occupational and environmental health services to that provided by general practitioners and other non-occupational and environmental health providers.

Yet a review of the College of Rural and Remote Medicine’s website confirms the absence of any internal occupational and environmental medicine courses. Furthermore, the only occupational and environmental health-related references in the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ ‘2016 Core Skills Unit’ of its ‘Curriculum for Australian general practice’ are two lines indicating that general practitioners are only expected to undertake an education and promotion role with respect to early return-to-work after work-related injuries or illness, and identifying opportunities to prevent injury and disease in at-risk individuals.13

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ curriculum offers ‘contextual units’ in military medicine and occupational medicine.14 Other contextual units of less direct relevance to the ADF include travel medicine, individuals with disabilities, musculoskeletal and sports medicine, adult medicine, men’s health, women’s health, psychological health, abuse and violence, and addiction medicine. However, all these units consist of 2-3 page summaries, each only describing the relevance of the topic in a general practitioner setting, with very limited further references regarding the actual skills required.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners has a Military Medicine Working Group, which is developing a post-fellowship Diploma of Military Medicine that includes modules in public health, and occupational and environmental health. However, neither of the relevant Faculties of Public Health or Occupational and Environmental Medicine have so far been involved in their development.15

Furthermore, the Australian and New Zealand Society of Occupational Medicine Inc, is a professional society for those who practice or have an interest in occupational health. It seeks to advance the knowledge, practice and standing of occupational health by providing opportunities for professional development, networking and partnerships.16 However, ‘garrison’ services have not yet mandated employing general practitioners from this or other occupational health organisations.

Civilian general practitioner training therefore provides a comprehensive basis for the clinical primary care of individual ADF members. However, it does not provide the full range of non-clinical primary care and other occupational and environmental health skills and expertise required for the ADF workforce. This further supports the author’s earlier assertion that it takes up to 12 months for new full-time general practitioners to understand how to assess medical suitability for ADF employment and deployment, even without considering any other military occupational and environmental health functions.

ADF medical officer career implications

Defence requires all uniformed, Australian Public Service and contract civilian medical practitioners to comply with the registration standards of the Medical Board of Australia. Service medical officers currently have a four-level career structure, linked to remuneration, as follows:

ML 1: new entry medical officers who have not yet met all the requirements to be operationally deployable under remote supervision, pending further medical studies and Service training courses. All permanent medical officers are expected to initially undertake primary health care roles before diversifying into other streams. In practice, however, ADF medical officer recruiting is almost exclusively premised on an eventual civilian general practitioner career.

ML2: medical officers who are deployable with remote supervision. Although it is intended that medical officers begin specialising into either clinical or management staff/force protection streams at this point, the aforementioned initial recruiting practices mean that exceptionally few are choosing the latter.

ML3: primary health care medical officers, with either a Royal Australian College of General Practitioners or College of Rural and Remote Medicine fellowship. Most medical officers choose to leave the ADF at this point, which generally coincides with the end of their return- of-service obligation.

ML4: medical officers who have achieved a qualification listed as a specialist medical qualification by the Medical Board of Australia, other than general practitioner. Among other specialties, it includes management/ staff/force protection specialties, such as medical administration, public health, and occupational and environmental medicine. However, in November 2016, there were only two permanent ADF occupational and environmental physician trainees, while public health and medical administration trainee numbers were probably comparable.17

An under-recognised medical officer retention factor pertains to the lack of diversity with respect to the clinical conditions experienced by the ADF workforce. Treating a succession of musculoskeletal and mental health disorders every day is unlikely to facilitate retaining Service or civilian general practitioner medical officers who prefer more clinical variety.

Consideration should therefore be given to recruiting and training more Service and civilian medical officers with an interest in an occupational and environmental medicine career. It is likely that they would not only maintain an interest in workforce primary health care, but also accept that their eventual career progression to non-clinical roles is more consistent with their occupational and environmental medicine aspirations compared to their general practitioner peers. These ‘garrison’ occupational and environmental physicians would also facilitate local Command compliance with the Work Health and Safety Act.

Conclusion

With ADF personnel arguably exposed to the most diverse range of occupational and environmental hazards of any Australian workforce, high rates of preventable workplace illness and injury indicate the need to improve the management of occupational and environmental health hazards, with better emphasis on prevention rather than treatment.

This suggests that the ADF’s health services should be premised on an occupational and environmental health paradigm, with revised fundamental inputs to capability that would lead to a genuinely holistic and sustainable workforce-based ADF health service delivery model by 2030.

Although general practitioners would still maintain an essential primary health care role within such a paradigm, they lack the skills and expertise to provide the full range of clinical and other occupational and environmental health services required for a young, fit, geographically mobile and predominantly male (although this is changing) ADF workforce.

However, occupational and environmental physicians have the skills and expertise to provide primary health care for workplace-related musculoskeletal and mental health injuries, as well as managing workplace-based rehabilitation, and assessing medical suitability for employment and deployment. Such a delivery model would entail recruiting and training more Service and civilian medical officers who are interested in an occupational and environmental physician career.

Dr Neil Westphalen graduated from Adelaide University in 1985, and joined the RAN in 1987. He is a RAN Staff Course graduate, and a Fellow of both the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. He also has a Diploma of Aviation Medicine and a Master of Public Health, and was admitted as a Foundation Fellow of the new Australasian College of Aerospace Medicine in 2012.

His seagoing service includes HMA Ships Swan, Stalwart, Success, Sydney, Perth and Choules. Deployments include Operations DAMASK VII, RIMPAC 96, TANAGER, RELEX II, GEMSBOK, TALISMAN SABRE 07, RENDERSAFE 14, KAKADU 16 and SEA HORIZON 17. His service ashore includes clinical roles at Cerberus, Penguin, Kuttabul, Albatross and Stirling, and staff positions at Headquarters Australian Theatre, Joint Health Command, Director Navy Occupational and Environmental Health, Director of Navy Health, and Fleet Medical Officer (the latter from January 2013 to January 2016). Commander Westphalen transferred to the Active Reserve in July 2016.