Abstract

Purpose: Yoga is considered a potential alternative treatment for sleep disorders in military veterans.

This study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to critically assess the best available evidence on yoga’s effects in managing sleep problems among military veterans.

Material and methods: A systematic search was conducted across four electronic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus and MEDLINE/PubMed), covering from their inception until October 2024. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and the Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After Studies with No Control Group scales.

Results: A total of eight studies met the inclusion criteria and were analysed. The main outcomes assessed were subjective sleep quality (n = 6), subjective insomnia (n = 2), and objective sleep status (n = 1). The meta-analysis, with data from 75 participants, indicated a significant improvement in subjective sleep quality after yoga interventions compared with baseline (Hedges’ g 0.40; 95% CI 0.12; 0.69, p<0.001). Overall, yoga positively affected both subjective sleep quality and subjective insomnia. While yoga appears safe for military veterans, its efficacy in improving objective sleep in this population has been underexplored.

Conclusion: The efficacy of yoga for sleep problems in military veterans is uncertain, primarily due to limited single-arm studies. Preliminary findings indicate potential benefits for insomnia, but more rigorous research is needed to assess its effectiveness.

Keywords: Insomnia; Physical Activity; Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Exercise.

Introduction

Sleep disturbance is a primary complaint among military veterans.1 These sleep problems often begin during or immediately after their military service and persist over time. The primary cause is typically inadequate coping mechanisms and/or poor stress regulation resulting from military experiences, leading to difficulty in falling or staying asleep.2

Among military veterans, untreated sleep problems significantly increase the risk of psychological distress, mental health disorders,2 and the development of cardiovascular disease.3 Despite these serious risks, sleep problems remain largely overlooked in primary care settings,1 even as the demand for sleep medicine services among veterans has increased substantially.4 In this context, identifying low-cost, non-specialised adjunctive interventions may help healthcare providers optimise treatment outcomes.

In this regard, complementary and integrative health approaches, such as yoga, may be considered an alternative treatment for sleep problems in military veterans.4 However, before adopting yoga as therapy for this population, health professionals must carefully evaluate its potential benefits and risks. This requires systematic reviews to summarise existing scientific evidence.

Yoga has proven to be an effective complementary approach for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alleviating symptoms like hyperarousal and emotional dysregulation.5 It also helps manage chronic neck pain, a common issue in this population,6 promoting both mental and physical wellbeing.

To date, the effectiveness of yoga as an alternative therapy for veterans has been reviewed through studies on mindfulness interventions, primarily focused on overall health outcomes, with few addressing its impact on sleep problems.7–9 To the authors’ knowledge, no comprehensive review solely on yoga and sleep issues has been published so far. Therefore, this study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to critically assess the best available evidence on yoga’s effects in managing sleep problems among military veterans.

Material and methods

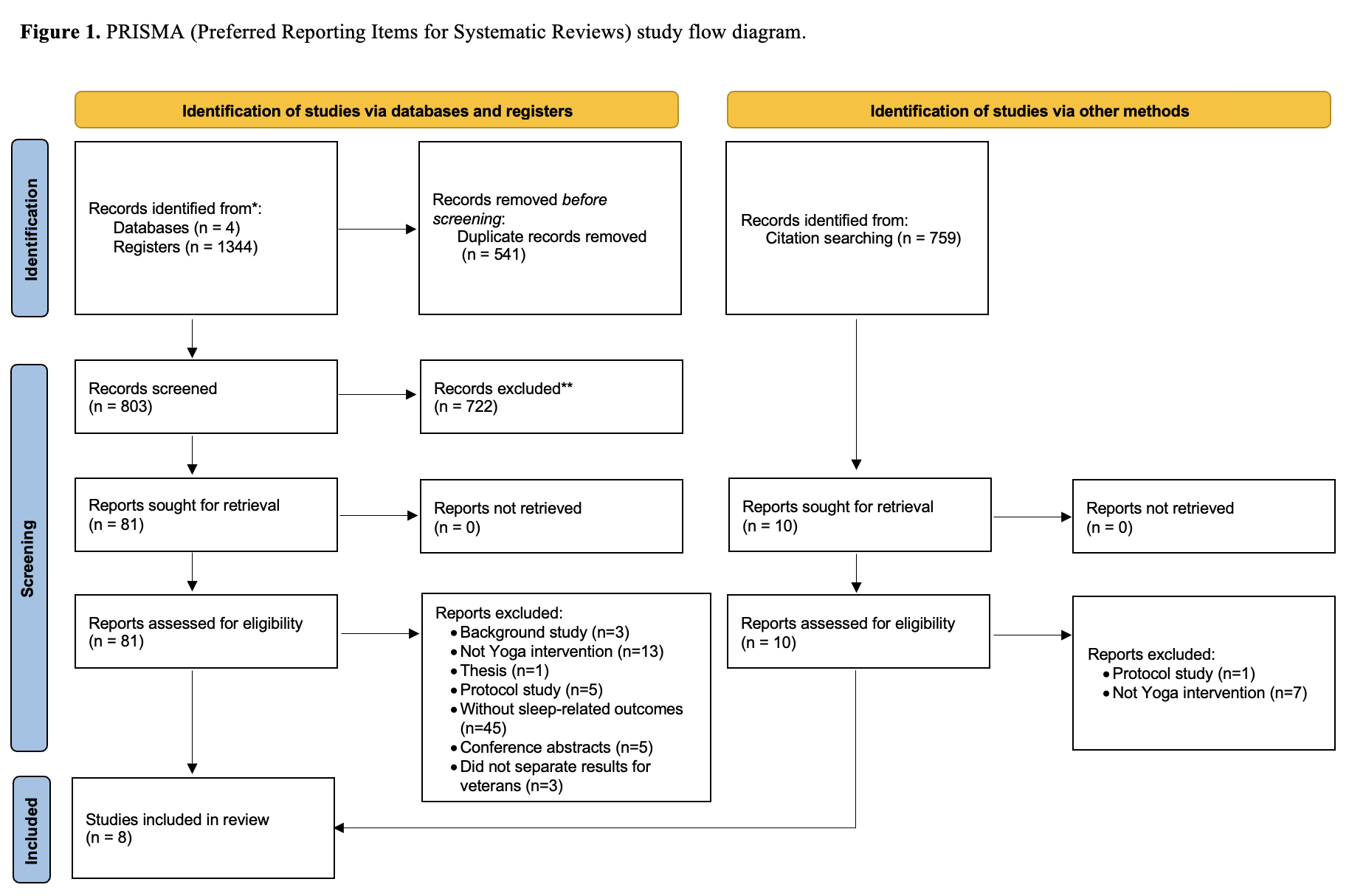

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on Open Science Framework (OSF, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8KYW6). The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines10 to ensure transparency and rigour.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted across four electronic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, and MEDLINE/PubMed), covering from their inception until October 2024. Additionally, a manual search was performed, reviewing the first 200 references from Google Scholar and the PEDro database.

Eligibility criteria

Studies exploring the effects of yoga on sleep-related outcomes in military veterans were considered for inclusion. The selection process followed the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework (Table 1). Only research articles published or accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals were included for the initial screening, while abstracts from conference proceedings, books, theses and dissertations were excluded. Additionally, the availability of an abstract was required for screening eligibility.

Table 1. Search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria based on PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome).

| Databases | Search terms | PICO | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE/ PubMed/ Web of Science/ SPORTDiscus/ Scopus |

(“Yoga”) AND (“Veteran*” OR “Militar*” OR “Soldier” OR “Army” OR “Defense” OR “Air Force” OR “Navy” OR “Marine” OR “Troops” OR “Special Forces”) | Population | Military Veterans |

|

| Intervention | Yoga programme |

|

||

| Comparison | Baseline measurement, control group or other structured interventions |

|

||

| Outcome | Sleep-related measures |

|

Study selection

The Rayyan software (QCRI, Qatar) was used to remove duplicate references before screening.11 Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the identified studies to assess their eligibility. Following this independent assessment, the reviewers compared their selections to reach a consensus based on the predefined inclusion criteria. Once an agreement was reached, full texts of potentially relevant studies were obtained. In cases where there was uncertainty about whether a study met the inclusion criteria, a third reviewer was consulted, and consensus was achieved in alignment with the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Data on sample characteristics, interventions, outcomes assessed, key findings, adverse events and participant dropouts were initially extracted from the original reports by one researcher. A second investigator then reviewed and verified the extracted information. The summarised data was compiled and presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of the included studies.

| First author (Year), design and country | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Results | Dropouts, adverse events and ITT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathersul et al. (2023) Design: RCT Country: USA |

Participants (n): 85 veterans with PTSD (EG: 41; CON: 44)Gender: EG: 33M + 8F; CON: 41M + 3F Age, years (mean; SD): EG: 57.4 ± 12.6 CON: 56.4 ± 12.9 |

Duration: 6-week EG Type: Sudarshan Kriya yoga Frequency: Initial 5-day workshop, then 2 days/week Volume: 60 min/session Intensity: NR CON Type: Cognitive processing therapy Frequency: 2 days/week |

Subjective sleep:

Objective sleep (actigraphy):

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05) ↑ Quality (diary) in EG and CON ↓ Latency (diary) in EG and CON ↓ Wake duration (diary) in EG and CON ↓ Nightmares (PCL-C/CAPS-5) in EG and CON ↓ Insomnia (PCL-C/CAPS-5) in EG and CONInter-group (p < 0.05) > Nightmares reduction in CON than EG > Insomnia reduction in EG than CON |

Dropouts: EG: 1 Lost, 6 scheduling conflicts, 2 travel problems, 1 death in family, 1 illness CON: 6 Lost, 2 scheduling conflicts, 3 did not like treatment, 2 wanted to focus on other things, 1 incarcerated, 1 admitted to inpatient psychiatryAdverse events: CON: 1 reported being distressed by the assignments. 1admitted to hospital for suicidal ideation.ITT: Yes |

|

Groessl et al. (2023) Design: RCT |

Participants (n): 29 veterans with PTSD (EG: 14; CON: 15)Gender: EG: 14M; CON: 11M + 4F Age, years (mean; SD): EG: 51.9 ± 13.5 CON: 40.1 ± 10.7 |

Duration: 12-week + 6-week follow-up Frequency: 1 day/week Volume: 75 min/session EG Type: Yoga and mantra repetition Activities: 15 min of instruction on mantra + 1h yoga Intensity: NR CON Type: Relaxation intervention Activities: Classroom instruction and group discussion |

Subjective sleep:

|

Intra-group (Cohen’s d) ↓ ISI in EG [-2.7 (1.6; -7.0); d = 0.37] after intervention and ↑ after follow-up period ↓ ISI in CON [-0.3 (-3.1; 2.5); d= 0.08] and ↑ after follow-up periodInter-group- NR |

Dropouts: Intervention period: EG: 1 lost to follow-up CON: 3 lost to follow-up Follow-up period: EG: 2 lost to follow-up CON: 3 lost to follow-upAdverse events: NOITT: No |

|

Zaccari et al. (2020) Design: |

Participants (n): 27 veterans with PTSD Final sample (n): 17Gender: 10M + 7F Age, years (mean; SD): M: 56.1 ± 9.47 F: 58 ± 4.32 |

Duration: 10-week EG Type: Trauma-informed yoga Activities: The facilitator was a recreational therapist and a registered yoga teacher Frequency: 1 day/week Volume: 60 min/session Intensity: NR |

Subjective sleep:

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05) ↓ PSQI score (13.88±4.87 vs 12.06±4.98) |

Dropouts: 10 lost to follow-upAdverse events: NRITT: No |

|

Groessl et al. (2020) Design: RCT |

Participants (n): 152 veterans with chronic low-back pain Final sample (n): 150Gender: EG: 55M + 20F; CON: 56M + 19F Age, years (mean; SD): EG: 53.3 ± 12.7 CON: 53.6 ± 13.9 |

Duration: 12-week + 6-months follow-up EG Type: Hatha yoga Activities: Included yoga postures, movement sequences and breathing techniques. 15–20 min of home practice was recommended on days without formal sessions. Frequency: 2 days/week Volume: 60 min/session Intensity: Moderate CON Type: Delayed-treatment Activities: Received ongoing usual care |

Subjective Sleep:

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05)-NR Inter-group (p < 0.05)- NO |

Dropouts: Intervention period: EG: 6 transportation, 4 non-yoga injury, 3 work, 3 other medical, 2 housing/homeless, 1 back pain, 1 type of yoga CON: 1 completely withdrew; 3 did not wait 6 months to use yoga Follow-up period: EG: 3 lost to follow-up CON: 8 lost to follow-upAdverse events: NOITT: Yes |

|

Cushing et al. (2018) Design: |

Participants (n): 23 veterans with PTSD Final sample (n): 18Gender: 9M + 9F Age, years (mean; SD): 43 ± 9.7 |

Duration: 6-week EG Type: Vinyasa yoga Activities: 10-min warm-up inclusive of 3–5 min of meditation; standing yoga 25 min; balancing yoga 10 min; mat yoga 10 min; resting position 5 min Frequency: 1 day/week Volume: 60 min/session Intensity: NR |

Subjective sleep:

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05) ↓ PSQI score (13±4.8 vs 9.7±3.9) |

Dropouts: 5 conflicts with work or school schedulesAdverse events: NRITT: No |

|

McCarthy et al. (2017) Design: |

Participants (n): 30 veterans with PTSD Final sample (n): 28Gender: 27M + 1F Age, years (mean; SD): 63.5±7.6 |

Duration: 8-week EG Type: Hatha yoga Activities: Conducted by a practitioner with qualifications in physiotherapy, yoga and mindfulness practices; supplemented with an audiovisual recording with instructions for home use. Frequency: 1 day/week Volume: 60 min/session Intensity: NR |

Subjective sleep:

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05) ↓ PSQI score (12.4±3.7 vs 11.19±4.1) |

Dropouts: 1 lost to follow-up, 1 declined further participation given the need for surgery related to an intercurrent illness. Adverse events: NRITT: No |

|

King et al. (2014) Design: |

Participants (n): 15 cancer survivor veterans Final sample (n): 14Gender: 13M + 1F Age, years (mean; SD): 65.64±5.15 |

Duration: 8-week EG Type: Yoga for People with Cancer & Chronic Illness program Activities: 2 days/week, and direction to complete 15 min of daily home practice at least 5 days/week. During application, substantial individualised modifications to yoga protocol were necessary. Frequency: 2 days/week Volume: 75 min/session Intensity: NR |

Subjective sleep:

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05)-NO | Dropouts: 1 completely withdrewAdverse events: NOITT: No |

|

Staples et al. (2013) Design: |

Participants (n): 15 veterans with PTSD Final sample (n): 12Gender: 10M + 2F Age, years (mean; SD): 62.2 ± 2.2 |

Duration: 6-week EG Type: KHYF yoga Activities: 3 min for self-awareness by ‘checking in’ with the body, mind and breath; 40 min of postures with breath awareness; and 5–10 min of full body relaxation focusing on extending the exhale and guided visualisation. Frequency: 2 days/week Volume: 60 min/session Intensity: NR |

Subjective Sleep:

|

Intra-group (p < 0.05) ↓ PSQI total score (14.6±2.6 vs 13.3±3.8) ↓ PSQI day time dysfunction score (1.9±0.8 vs 1.4±0.8) |

Dropouts: 3 withdrew during interventionAdverse events: NOITT: No |

>: Greater; <: Lower; ↑: Increment; ↓: Decrement; BMI: Body Mass Index; CAPS-5: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; CON: Control Group; KHYF: Krishnamacharya Healing and Yoga Foundation; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; ITT: Intent-to-treat; F: Female; IG: Intervention Group; M: Male; NO: Not Observed; NR: Not Reported; PCL-C: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version; PROMIS: Patient- Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PTSD: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by two authors using quality assessment tools appropriate for the study type. This included the PEDro scale and the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group. The PEDro scale, as reported in previous studies,12 scores methodological quality from 0 to 10. Studies with PEDro scores below 4 were classified as having ‘poor’ methodological quality, those scoring between 4 and 5 were considered of ‘fair’ quality, scores from 6 to 8 were categorised as ‘good’ quality, and scores of 9 or 10 indicated ‘excellent’ quality.13 The NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies assigns an overall score that is categorised as ‘low’ (75–100%), ‘moderate’ (25–75%), or ‘high’ (0–25%). This score is calculated as the sum of the scores for each criterion divided by 12.14

Statistical analysis

We conducted the meta-analysis calculations using Microsoft Excel and the Meta-Essentials Workbooks,15 employing Hedges’ g to determine the effect size for quantitative dependent variables. We applied a random-effects model in all analyses to account for potential heterogeneity across studies, utilising the inverse variance method.

To evaluate statistical heterogeneity and inconsistency, we used the I2 statistic. An I2 value of 0% indicates no detectable heterogeneity, while higher values signify increasing heterogeneity. Alongside 95% confidence intervals (CI), we also calculated prediction intervals to represent the magnitude and consistency of the effects.

Results

Design and samples

Out of the 1344 records initially obtained, a total of eight studies, three randomised controlled trials (RCTs),16–18 and five single-arm studies19–23 were finally analysed (Figure 1). All the investigations were published between 2013 and 2023. A summary of their main characteristics is provided in Table 2.

The total sample size from across all investigations was 376 participants; the smallest and largest study sample included 1520,22 and 15216 participants, respectively. According to the obtained data, most participants were male, comprising approximately 76% of the total. Six studies focused on veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),17–19,21–23 one on cancer survivor veterans20 and another on veterans with chronic low-back pain.16

Interventions characteristics

The types of yoga included yoga with mantra repetition, Sudarshan Kriya yoga, trauma-informed yoga, Hatha yoga, Vinyasa yoga, KHYF yoga, and the Yoga for People with Cancer & Chronic Illness program. Yoga interventions lasted between 618,19 and 12 weeks,16,17 with sessions ranging from one to two times per week. Session durations varied from 60 to 75 minutes. No study controlled the session’s intensity, although Groessl et al.16 indicated it was moderate.

Main outcomes

Subjective sleep quality

Six of the eight included studies analysed the effects of yoga on subjective sleep quality16,18,19,21–23 and five of them reported significant intra-group improvements after intervention.18,19,21–23

Only two studies analysed inter-group differences. Notably, one study13 did not find the effects of yoga to be superior to control conditions. In contrast, Mathersul et al.15 reported a greater reduction in nightmares in the group that underwent cognitive processing therapy compared to the group that practised Sudarshan Kriya yoga.

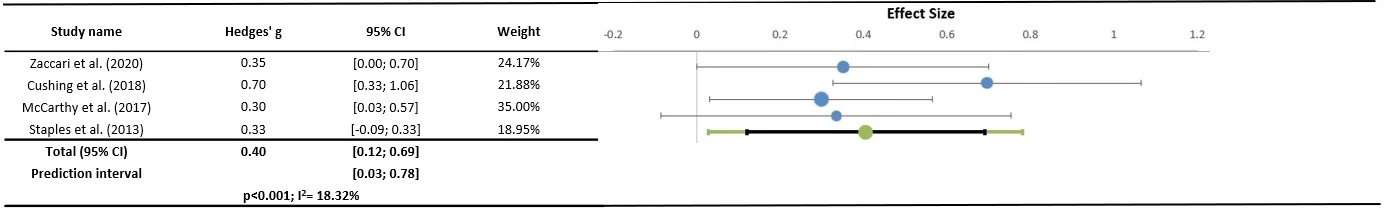

The meta-analysis comparing pre- and post-intervention results in four yoga studies19,21–23 (n = 75) revealed a significant positive effect of yoga on subjective sleep quality (Hedges’ g = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.12–0.69, p < 0.001), with low heterogeneity (I² = 18.32%), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Evaluation of Methodological Quality.

Subjective insomnia

Three studies analysed the effects of yoga on insomnia and two reported significant intra-group improvements after intervention.17,18 However, King et al.20 did not observe any statistically significant changes in insomnia.

Two studies analysed inter-group differences,17,18 but only Mathersul et al.18 reported a significantly greater reduction in insomnia in the group that practised Sudarshan Kriya yoga than those who underwent Cognitive Processing Therapy.

Objective sleep

Sudarshan Kriya yoga program did not significantly impact objective sleep outcomes according to the results reported in the only study investigating this outcomes.18

Dropouts and adverse events

Ninety dropouts were observed across all the studies included, 55 occurring in the yoga groups. The primary reasons for dropouts included health issues, transportation and/or discontinued intervention. No study reported any adverse effects related to the yoga program.

Methodological quality

The three randomised studies analysed had good methodological quality, with scores ranging from 618 to 8.16,17 However, no studies were blinded to participants or therapists (Table 3). The non-experimental studies showed moderate methodological quality, with scores from 523 to 8.20 Although the samples were generally representative of the studied population, they were small (Table 4).

Table 3. Evaluation of methodological quality (PEDro scale) of RCT studies

| Scale items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathersul et al. (2023) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Groessl et al. (2023) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Groessl et al. (2020) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Items: 1. Eligibility criteria and source 2. Random allocation 3. Concealed allocation 4. Baseline comparability 5. Blinding of participants 6. Blinding of therapists 7. Blinding of assessors 8. Adequate follow-up (. 85%) 9. Intention-to-treat analysis 10. Between-group statistical comparisons 11. Reporting of point measures and measures of variability

Table 4. Evaluation of the quality assessment tool for before-after studies with no control group scales.

| Scale items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Score | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaccari et al. (2020) | Y | Y | Y | CD | N | N | Y | NR | N | Y | N | N | 5 | M |

| Cushing et al. (2018) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | 7 | M |

| McCarthy et al. (2017) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | CD | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | 6 | M |

| King et al. (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | 8 | M |

| Staples et al. (2013) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | 7 | M |

Key: Y = Yes, N = No, NR = Not reported, CD = Cannot determine, NA = Not applicable, M = Moderate

Items: 1. Study question 2. Eligibility criteria and study population 3. Study participants representative of clinical populations of interest 4. All eligible participants enrolled 5. Sample size 6. Intervention clearly described 7. Outcome measures clearly described, valid and reliable 8. Blinding of outcome assessors 9. Follow-up rate 10. Statistical analysis 11. Multiple outcome measures 12. Group-level interventions and individual-level outcome efforts

Discussion

Yoga has demonstrated effective management of sleep disturbances across various conditions.24,25 However, the findings of this review do not fully support these results. For instance, most of the analysed studies reported data on the effects of yoga on sleep quality, with the majority showing significant intragroup improvements for this outcome. This finding was confirmed after meta-analysing data from four investigations. This result is somewhat expected, as it has been suggested that yoga enhances sleep quality by increasing melatonin levels, reducing hyperarousal, and addressing stress-related cardiac and respiratory abnormalities.26 However, when yoga was compared to control conditions, its effects were inferior to simple relaxation exercises. Additionally, cognitive therapy proved to be more effective in improving sleep quality. Notably, other therapies, such as simple walking, have been shown to have greater effects than yoga in adults suffering from sleep disturbances.27 Together, these findings suggest that yoga might not be the most suitable therapy to recommend for managing sleep quality in military veterans. These results also highlight the challenge of improving sleep quality through exercise therapy in this population, as previously observed.28,29

In this line, mixed results were observed for insomnia, as not all analysed studies reported significant improvements. Furthermore, its effects were not superior to those of relaxation exercises. However, yoga appeared to be more effective than cognitive therapy in managing insomnia. This is a noteworthy finding, as both the A/DOD Clinical Practice Guidelines and the recommendations from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Physicians and the National Institutes of Health identify cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with insomnia. Additionally, the Department of Veterans Affairs has invested significantly in disseminating CBT-I as a preferred treatment option for veterans.30 Given that healthcare systems should adopt evidence-based clinical practice standards for treating insomnia among military veterans,31 healthcare providers might consider the potential benefits of prescribing yoga to this population as a complementary therapy.

Yoga is a feasible intervention for the treatment of diverse symptoms such as PTSD or low-back pain among military veterans.32,33 Indeed, yoga is a complementary therapy that seems to be widely accepted by military veterans.34 However, in this review, a considerable number of dropouts were reported, most of them related to health issues or lack of transportation, which calls into question the feasibility of recommending yoga practice among military veterans with sleep problems. In this regard, implementing hybrid yoga sessions—combining remotely delivered and in-person formats—could enhance adherence by addressing common barriers military veterans face, such as transportation challenges, time constraints and financial limitations.35 This flexible approach may improve accessibility and encourage long-term engagement in yoga-based interventions.

This appears to be the first review of the efficacy of yoga for managing sleep problems among military veterans. Its primary strength lies in its novelty. However, a key methodological limitation is the lack of studies incorporating objective sleep assessments. While subjective measures, such as self-reports, provide valuable insights into individuals’ perceptions and psychological influences on sleep, objective methods, like actigraphy, offer quantifiable and replicable data that enhance assessment accuracy.36 Future research should integrate both subjective and objective sleep measures to ensure a more comprehensive evaluation.

Despite its originality, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, only a small number of studies were included. Secondly, there was a lack of comparison groups, and heterogeneity was high, preventing the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis. Thirdly, participants in the reviewed studies were predominantly male, limiting the applicability of the findings to the female population. Finally, excluding grey literature and potential publication bias may have also influenced the results.

Conclusion

The available scientific evidence on the effects of yoga on managing sleep problems among military veterans comes from a reduced number of studies, most of them using a single-arm design. Preliminary findings cast doubt upon the efficacy of yoga for improving sleep quality, while its practice can help manage insomnia. Further studies that accurately test the feasibility of this therapy in this population are strongly needed.

Conflicting interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict-of-interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from public, commercial or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Corresponding Author: Rocío Carballo Afonso, rociocarballo@uvigo.gal

Authors: R Carballo Afonso1, D González-Devesa2, L Iglesias Vieites3, C Ayán Pérez1

Author Affiliations:

1 Universidad de Vigo – Didácticas Especiáis

2 Universidad Católica de Ávila

3 Independent researcher