Abstract

This paper aims to provide some initial thinking on determining the basis for assessment of the existence, severity, and nature of a Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I) within an individual. The conditions, behaviours, and Red-Actions (serious, life-threatening, harmful) actions of an SW&I discussed in an earlier paper in this journal1 require a thorough and rigorous assessment if they are to be managed effectively. The first step in developing this tool will be to review existing MI and spiritual assessment tools against the SW&I concepts discussed to date. Several existing assessment tools will be considered. While each has value and presents opportunities for greater understanding, none of them addresses the entire scope of a SW&I. Following this, the SW&I Assessment Tool – Provisional (SW&IAT-P) will be proposed, and its potential uses will be described. The proposed SW&IAT-P is a purpose-built and multidisciplinary tool that medical, psychological and spiritual practitioners can use. The SW&IAT-P is classed as provisional, as it will require further development that is outside the scope of this paper and the research conducted to date. The author seeks comments from all sectors on this paper.

Triage vignette

Imagine a scene where a soldier is brought into a deployed field ambulance on a stretcher. The stretcher is placed on a table surrounded by several different practitioners. In one scenario, the soldier is suffering a significant gunshot wound (GSW) to the stomach. Accordingly, the surgeon takes over. In another scenario, or perhaps at the same time, the soldier is running a high-grade fever, so a general practitioner steps forward. In yet another scenario, the soldier is assessed as clinically depressed, and so the psychologist or psychiatrist contributes to the treatment. Possibly, the soldier also shares that they are depressed as they feel that God no longer loves them because of what they have done.2 At that point, a religious/spiritual practitioner (RSP) may take up their care as the soldier may exhibit a SW&I.1

There are a few points that need to be noted about this scene. First, it is highly likely that given the complexity of modern warfare, the soldier would be suffering from a number, if not all, of these conditions. While the most life-threatening will need to be dealt with first, the overall care of the soldier will be managed by a multidisciplinary team of appropriately trained and qualified practitioners. The course of treatment for some cases, such as the GSW, may initially seem obvious. However, each practitioner will invariably carry out a complex diagnosis and assessment process based on the requirements of their discipline. The thoroughness and rigour of those assessments will significantly contribute to the success of the management of the condition. As a part of that multidisciplinary team, the RSP will likewise need to complete their own equally rigorous assessment.

This is also not necessarily first aid and may be years after the initial trauma when the soldier has returned and is now a veteran. At that time, this scene may be played out in doctor’s surgeries and consulting rooms, psychologists’ offices or even a church rectory. Regardless of location, the first step for whichever practitioner will be to assess the situation thoroughly. This paper discusses a SW&I assessment approach for RSP and perhaps other supporting professionals such as medical doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists.

The initial focus of this paper will be to revisit the concept of the SW&I that was discussed in a previous article in this journal.1 Following this, there will be a review of existing Moral Injury (MI), psychological and spiritual assessment cases and tools against the SW&I concept. A SW&I assessment tool, the SW&I Assessment Tool – Provisional (SW&IAT-P), will be proposed and its potential uses will be described.

The SW&IAT-P is classed as provisional as, although it has been based on the research to date, it will require further development. This will include confirmation of the steps and processes identified to this point, development of a more fulsome and robust set of questions, and development supporting metrical analysis. These steps will all require the conduct of trials and evaluation activities. Community input and suggestions in this area will be most welcome.

SW&I

In a previous paper in this journal, the issue of spiritual damage occurring to veterans because of traumatic events was discussed.1 To date, spiritual damage occurring to veterans because of traumatic events has been typically looked at through the lens of MI. While useful in part, this approach is not entirely appropriate or compelling, not least because it does not adequately cover spiritual dynamics such as the presence of God or a Divine figure. Further, the current MI paradigms seldom allow for consideration of spiritual damage outside of the aftermath of a morally injurious experience (MIE). MI is not a mental illness, and while some of its hallmark behaviours may respond to psychological, psychiatric, pharmacological or spiritual approaches, the essential basis of a MI lies in a disruption of a person’s moral relationship with another person, group or society. Morality and spirituality are related but distinct terms. A SW&I focuses on a broken relationship between an individual and their concept of a God. As such, MI is to the many as SW&I is to the one.

Health, morality and spirituality are fundamentally different disciplines. MI does not fully address the impact of the spiritual damage upon the spiritual ‘head and heart’ of a person’s identity. Recent research has suggested that head-and-heart spirituality are neither exclusive nor in competition, but one may be dominant depending upon an individual’s spiritual, religious and cultural background.3 In terms of heart spirituality, Madeline Anderson suggested in 2020 that there is a:

‘Central and bidirectional relationship between the heart, the “Master Organ,” and the phenomenology of spiritual experience. Further, we provide existing evidence for a synergistic, salutogenic relationship between robust cardiac function and spiritual well-being that may offer a roadmap to spiritual, psychological, and physical recovery and health at the individual, interpersonal and global levels’.4

The concept of a spiritual heart is that an emotional experience may be influenced not only by the head but also by a heart-head axis. This influence should be recognised as spirituality and emotions are inextricably linked, and spiritual experiences are intertwined with the generation of positive emotions such as awe, appreciation and joy.4 Joshua Daniel (2016) takes this idea of separation between head and heart further by highlighting differences in the approach to managing spiritual damage. He notes that, as ‘PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] demands a medical response, an instance of professional expertise,’ a ‘spiritual wound, MI demands an in-kind response: on the one hand, spiritual, and so irreducible to head chemistry; on the other hand, communal, not a task to be delegated to professionals or experts’.5 The implication here seems to be that spirituality is ‘so irreducible to head chemistry’ that linking it to psychological disorders such as PTSD and, by extension, psychiatric and psychological therapies such as MI are unlikely to provide appropriate responses.5

To comprehensively understand the effects of traumatic events on an individual’s spiritual health, the previous paper in this journal proposed a new integrated term to describe such damage, ‘Spiritual Wounds and Injuries’. The following definition of SW&I was introduced for further discussion:

‘A Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I) occurs when an individual’s perceptions of God, either through direct engagement (spiritual wound) or facilitated through a faith community (spiritual injury), are damaged or changed by an event or events. A spiritually wounded and injured individual may feel they have failed God by not acting in a way that would not warrant his love. Conversely, the individual may feel an omniscient, omnibenevolent, and omnipotent God deliberately chose not to help or support them and/or others in a way that would demonstrate his love for humankind as they would have expected, based on their spiritual schema. The fact that an individual loses faith in God is not the SW&I; rather, it is the effect that loss of faith has on some individuals’ mental health and overall well-being and how that might present in behaviours such as substance abuse, depression, or anger’.1

Not every individual has a religious or spiritual belief system. For those who do, threats to this system can significantly affect their lives. Visible behaviours such as substance abuse, depression or anger may follow a similar trajectory to conditions such as MI or other mental health concerns. However, their origin, nature and management will differ. The critical issue that separates SW&I from MI and mental health concerns is that SW&I is governed by head-and-heart spirituality and the individual’s relationship with God.

SW&I assessment

There is anecdotal evidence that some RSPs feel uncomfortable using assessment tools such as the proposed SW&IAT-P.2 Some RSPs feel that such assessment tools are the preserve of science-based practitioners such as psychologists and medical personnel, and they wish to be thought of differently. There is also a perception that such tools are more frequently used in a suicide management process. While the prevalence of this belief is unknown, RSPs need to become more comfortable with such tools. This is because such an approach is:

- Foundational. Tools such as the SW&IAT-P can provide a strong foundation for assessing the existence of a SW&I within a patient and the balance between spiritual injury (head) and spiritual wound (heart). In turn, this will also assist with selecting the best approaches to managing SW&I.

- Equivalent. RSPs work in an unscientific paradigm as opposed to their psychological and medical peers. Despite this, they must still be able to demonstrate to their peers that their management plans for the spiritual care of patients are based on equally valid needs assessments. This is particularly important if SW&I is to be approached as a part of the combined treatment process.

- Multidisciplinary. The author has previously discussed an example of a soldier who was feeling depressed because he thought that God no longer loved him.2 In the event, this individual may have initially presented to a general practitioner as their concerns appear as depression, although their origin is spiritual. There is no presumption that tools such as the SW&IAT-P cannot be multidisciplinary tools used equally by spiritual, moral, psychological and medical practitioners. Indeed, such usage is to be encouraged as it is very much in line with the bio-psycho-social-spiritual treatment model.6

Types of current assessments

The American Psychological Association (APA) notes that there are two broad approaches to understanding potential conditions based on patient presentation. On one level, there are screening activities. Screening identifies individuals at potentially high risk for a specific condition or disorder that will indicate a need for further evaluation or preliminary intervention. Screening is neither definitively diagnostic nor a definitive indication of a specific condition or disorder.7

On the other hand, assessment refers to a complex activity integrating knowledge, clinical judgment, reliable collateral information and psychometric constructs with expertise in professional practice or application. Psychological assessment is a problem-solving process of identifying and using relevant information about individuals, groups or institutions for decision-making and recommendations.7 Formal assessments seek to provide a complete clinical picture of an individual, focusing on the functioning across multiple domains. It aids in diagnosis and treatment planning by identifying problems and conditions, indicating their severity and providing treatment recommendations.

The same logic applies to SW&I. Accordingly, the SW&IAT-P will continue to be developed as a formal assessment and will seek to provide a spiritual picture of an individual that might aid in identifying problems and conditions and indicating their severity. Additionally, the SW&IAT-P may ultimately provide the basis for treatment recommendations. Several existing MI and spiritual assessment tools partially meet this need and provide a useful starting point for the discussion as they identify common trends and potentially relevant areas for inclusion.

Moral injury assessments

MI is still an evolving concept, and there is no generally accepted definition of MI. Likewise, there is no overarching structure or governance model for MI. As such, any assessment tools developed are not representative of the whole MI discipline but rather individual academic and, in some cases, institutional concepts. Despite this, there is a wealth of scholarship produced over the last 40-plus years, as well as several MI assessment tools that have been developed. The scholarship and tools are important as they may provide some insights into the eventual shape and structure of the SW&IAT- P. These tools are summarised in Annex A. The scopes of three of the most common and relevant tools are described below:

- Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version. The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version (MISS-M) is a 45-item measure of MI symptoms. It was designed for both veterans and serving personnel diagnosed with PTSD. Like many MI-related tools, the link between MI and PTSD is often present. The MISS-M correlates strongly with PTSD severity, depression, and anxiety symptoms, indicating convergent validity, although it is relatively weakly correlated with social, spiritual and physical health constructs. Importantly, this is used to identify discriminant validity or the discrimination concepts of measurements that are supposed to be related but are unrelated.8

The MISS-M consists of 10 theoretically grounded subscales that assess the psychological and spiritual/religious symptoms of MI. These are guilt, shame, betrayal, moral concerns, loss of meaning/purpose, difficulty forgiving, loss of trust, self-condemnation, spiritual/religious struggles and loss of religious faith/hope. The scale has high internal reliability, test-retest reliability and a factor structure that can be replicated. The MISS-M was the first multidimensional scale that measured both the psychological and spiritual/religious symptoms of MI and is a reliable and valid measure for assessing symptom severity in clinical practice and in conducting research that examines the efficacy of treatments for MI in Veterans and Active-Duty Military personnel. There is also a short-form version of the tool.9,10

- Expressions of Moral Injury Scale‑Military Version. The Expressions of Moral Injury Scale-Military Version (EMIS-M) was developed to provide a reliable and valid means for assessing the warning signs of a MI in military populations. Using independent samples of veterans who had served in conflict environments, factor analytic results revealed two distinct factors related to MI expressions directed at both self (9 items) and others (8 items). EMIS-M scores demonstrate strong convergent, divergent and incremental validity. EMIS-M has provided a validated tool for assessing expressions of apparent MI subtypes in research and clinical settings. EMIS-M’s development aims to advance the scientific understanding of MI while supporting innovation for clinicians to tailor evidence-based treatments and/or develop novel approaches for addressing MI in their work.11

- Moral Injury Outcome Scale. The Moral Injury Outcome Scale (MIOS) is currently under development by an international consortium. The aspiration is that the MIOS will be a measure of moral injury as a multidimensional outcome associated with exposure to potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs). Items will address six domains of impact, each with sub-components: alterations in self-perceptions (e.g., loss of trust in self as a moral agent); alterations in moral thinking (e.g., judgmental thoughts or appraisals of others); social impacts (e.g., expecting rejection or judgment); self-harming and self-sabotaging behaviours (e.g., engaging in risky behaviours); emotional aftermath (e.g., shame, guilt); and beliefs about life meaning and purpose (e.g., loss of religious or spiritual beliefs or practices). The first phase involved interviewing service members, veterans and mental health providers to generate initial content domains and 34 potential MIOS items. In the second stage of psychometric development, the 34-item version of the MIOS was administered to veterans and service members to examine reliability and items using exploratory factor analyses. Results from second-stage analyses led to a 14-item version of the scale.12 The MIOS is currently undergoing its third and final stage of psychometric evaluation. The MIOS has demonstrated acceptable initial reliability and content validity.13

Spiritual assessment approaches

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) 2019/2021 describes spiritual assessments as ‘initial and subsequent assessment of well-being issues, needs and resources of a client.14 It notes that the provision of this may include:

‘Establishing of relationship/engagement with another, hearing the story, and enabling pastoral conversation in which spiritual well-being and healing may be nurtured, supported and companioning persons confronted with profound human issues of death and dying, loss, meaning and aloneness. Predominantly a ‘ministry of presence and support’ Pastoral counselling or education’.14

While this is a useful description, as Carey and Cohen note, it is not yet widely used or discussed.15 Additionally, the very nature of spiritual engagements makes them difficult to describe scientifically or even consistently. This is because such engagements are perception-driven. These perceptions relate to how some individuals see, feel or hear the voice of God in their lives. This may be directly from God or a Divine figure through either a ‘still small voice’ (1 Kings 19:11-13) or communications that are more dramatic and Damascene (Acts 22:6). Their perceptions may also be developed through the facilitation of faith and religious education and the guidance provided by RSP delivered on behalf of God or Gods. In this case, assessment may be easier because most Holy Scriptures and works of religions often specify or command what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’.

In both cases, the focus of the SW&I assessment does not refer to the validity of or the means through which the perception is formed. RSPs, regardless of their spiritual or religious affiliation, should initially seek to use spiritual assessment tools to understand the nature of the SW&I and not to proselytise for their religion. This may come later if the specific nature of the SW&I necessitates such action and if the individual requests it. Likewise, non-spiritual practitioners of every discipline must accept that some individuals have faith or spiritual beliefs and should not seek to question or alter this. A tool such as the SW&IAT-P seeks to understand the effects upon an individual’s spiritual health that may have occurred because of a TPE or traumatic event.

Several spiritual assessment tools have been developed. Like MI assessments, aspects of these tools may have some utility for developing the SW&IAT-P. These tools are summarised in Annex A. Additionally, the scopes of three of the most common and relevant tools are described below:

- FICA Spiritual History Tool. The FICA Spiritual History Tool was created by Christina Puchalski in 1996 to assist with efficiently integrating open-ended questions into a standard medical history and can be used by healthcare professionals. The FICA tool is based on four domains of spiritual assessment: the presence of faith, belief or meaning; the importance of spirituality on an individual’s life and the influence that belief system or values has on the person’s health care decision-making; the individual’s spiritual community; and interventions to address spiritual needs.16

- HOPE questions. HOPE Stands for H = Sources of hope, strength, comfort, meaning, peace, love and connection; O = the role of organised religion for the patient; P = personal spirituality and practices; and E = effects on medical care and end-of-life decisions their religion. It also allows those for whom religion, God or prayer is important to volunteer this information.17

HOPE Questions were developed as a teaching tool to help medical students, residents and practising physicians begin incorporating a spiritual assessment into medical interviews. The strength of this approach is that it allows for an open-ended exploration of an individual’s general spiritual resources and concerns and serves as a natural follow-up to a discussion of other support. It does not immediately focus on the word ‘spirituality’ or ‘religion’. This minimises barriers to discussion based on the use of language. These questions have not been validated by research.

- Spiritual Index scale. The Berg Spiritual Index (SI) scale is a guide to a patient-focused, scripted dialogue between a provider and a patient. It is different from other assessment tools in that it looks at culture and spirituality simultaneously. The SI is a self-assessment instrument that investigates the degree of difficulty a person has with eight spiritual injuries. These eight items are guilt, anger/resentment, sadness/grief, lack of meaning/purpose in life, despair/hopelessness, feeling that life or God has been unfair, worry over religious doubt or disbelief, and fear of death.18

Spiritual Wounds and Injuries Assessment Tool-Provisional: a new tool

Several robust assessment tools exist across the MI and mental health paradigms. The preceding discussion on existing spiritual and MI approaches to assessment raises some relevant points that should be considered for developing and using a SW&IAT-P. A separate spiritual assessment tool that seeks to develop a better understanding of the nature and effects of damage to a person’s spiritual health following a traumatic event is still necessary. There are several reasons for this:

- Existing MI and mental health tools have undergone rigours evaluation and testing before being fielded. The MIOS, for example, is undergoing an international evaluation currently. The un-validated tests are still useful as a starting point as they highlight raw concepts that may be transferrable to SW&I assessment. As the SW&IAT-P is a new tool for a new field or discipline and may be a starting point for similar assessments, it will need to undergo a similar regime to the MIOS to be an effective measure of SW&I.

- Many of the MI and spiritual assessments use a form of Likert-type scale. This is a psychometric scale named after its inventor, American social psychologist Rensis Likert, and was developed for use in research questionnaires.19 Typically, it is used to scale responses in survey research. Likert scales range from 1 to 10, with 3, 5 or 7 being the most common. Further, this progressive scale structure is such that each successive Likert item is treated as indicating a better response than the preceding value.20 There is some criticism that the scale of the numbering system is arbitrary as there is no objective numerical base or distinction between number sets such as 1–2 or 3–4.21 This can be mitigated by broadening the scale from 1–5 to 1–10. The scale will support the initial aims of the SW&IAT-P, although it will be further qualified when the tool receives detailed testing.

- MI still reflects a robust scientific/medical approach that does not necessarily accord with aspects of SW&I’s more mysterious and amorphous aspects. Acknowledging these limitations, MI’s more doctrinaire approach may suit aspects of a SW&I that relate to how individuals react to breaches of commandments and holy laws. If a tool such as the SW&IAT-P can use aspects of tools such as MIQM, MISS-M, EMIS-M or MIOS (when fully developed), it may help in determining if an individual’s approach to spirituality is more head-based and reflective of religious education or upbringing. As such, a RSP with a stronger background in a relevant faith doctrine and dogma might be more appropriate to work with an individual bearing a SW&I of that nature.

- There are significant difficulties in measuring humankind’s spiritual engagement with God/Gods. This is mainly because such engagement is deeply personal and not observable to third parties. Many of the available spiritual assessment tools are linked to specific medical conditions such as oncology and end-of-life. These may be difficult to translate into a veteran circumstance if those conditions do not apply. At the same time, there appear to be several potentially useful tools already available that may provide a useful basis. HOPE and FICA are well developed, although they are narrow in their coverage. The Spiritual Well-Being Scale, Spiritual Assessment Inventory, Spirituality Index of Well Being, and the Berg SI scale are comprehensive tools that should be used to add to the shape and structure of the SW&IAT-P.

Assessment tool criteria

The structure of the SW&IAT-P will inevitably evolve with the development of a more fulsome and robust set of questions supporting metrical analysis and the conduct of rigorous trials and evaluations. Initially, the provisional assessment will be developed using the American Psychological Association’s guidance on the basic psychometric properties of tests.22 This guidance indicates that the basic properties of tests should include the following:

- Reliable. Repeated administration of the test would yield the same result.

- Valid. Test scores adequately represent a test‐taker’s standing on the psychological variable of interest, e.g., an individual’s level of anxiety.

- Accurate. The cut-off scores are used to indicate whether a test‐taker has, or is at risk for having, a specific condition, e.g., to demonstrate that individuals with depression will score at or above a designated cut-off score.

- Fair. The extent to which the test scores are equally reliable and valid for various segments of the population. This is particularly important given that ADF veterans’ range in age from 18 to 100 years of age.

- Norm adequate. Reference groups used to assist in test score interpretation adequately represent the population for which a test is designated.

- Relevant. Have information about the specific characteristics of the individual being assessed, e.g., race, gender, language, disability, etc.

- Administered and evaluated. Conducted by practitioners with expertise in test administration and scoring.

There is a further criterion that will need to be met. The Cambridge Psychometrics Centre also notes that tests must be standardised and free from bias.22 This is important to note on two levels. Firstly, to ensure that the SW&IAT-P is not aligned or even reflective of a religious or faith bias. It must be applied in the same way that chaplaincy is in the ADF: the provision of ‘spiritual and pastoral support to Army’s people by bringing honour to the dead, comfort to the sick, hope to those in distress, and support to all’.24 This spiritual and pastoral support is provided ecumenically and not just by specific RSPs to their specific faith group or denomination. Thus, the SW&IAT-P must be ecumenical. Related to this is any potential actual or perceived bias from the individual practitioner administering the test regarding their personal beliefs as to the overall existence of God and a spiritual domain. Just as not all veterans have such beliefs, nor will all supporting practitioners. The practitioner’s conduct of the SW&IAT-P must be free from their faith, cultural or academic beliefs.

Next steps

SW&IAT-P is classed as provisional as, although it has been based on the research to date, it will require further development. This further development will likely involve refinement of the questions, the scoring mechanism and the overall approach. This will include confirmation of the steps and processes identified to this point, development of a more fulsome and robust set of questions, and development supporting metrical analysis, all of which will require the conduct of trials and evaluation activities. Cues for this review may be taken from the example provided by the development MIOS. Community input and suggestions in this area will be most welcome.

SW&IAT-P

The SW&IAT-P utilises many aspects of the MI and spiritual assessment tools discussed above and in Annex A. For example, it takes inspiration from the MIOS by addressing domains of impact, each with its sub-components. This includes alterations in self-perceptions and moral thinking, social impacts, self-harming and self-sabotaging behaviours, and emotional aftermaths such as shame and guilt. Additionally, it considers beliefs about life meaning and purpose and where these may have been influenced by the loss of religious or spiritual beliefs. Unlike some MI assessments, the SW&IAT-P is not structured to reflect or contribute to the assessment of medical or psychological conditions such as PTSD.

In terms of spiritual assessment, the SW&IAT-P, like Puchalski’s FICA Spiritual History Tool, seeks to establish a tool that integrates open-ended questions into a standard medical history and can be used by other allied professionals for assessments. Applying the SW&IAT-P does not require deep or specialist theological or religious training or understanding. Berg’s SI scale has also been an important guide for developing the SW&IAT-P because of its patient-focused, scripted dialogue between providers and patients. It is also an important influence on how it simultaneously looks at culture and spirituality. This a relevant consideration given that SW&I occur not just within the more common cultural dimensions of religion/spirituality and the characteristics of the broader society but within the complex, unique and multi-layered military culture.

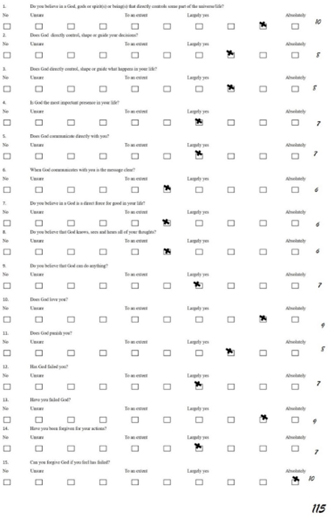

The SW&IAT-P is an assessment instrument that investigates the degree of difficulty a person has with eight spiritual injuries. The SW&IAT-P is described in Annex B. While each of the tools identified in Annex A has value and presents opportunities for greater understanding, they do not look at the whole scope of what may be considered SW&I. The proposed SW&IAT-P is a purpose-built assessment tool for this task. When complete, the tool should be treated as a confidential document. The tool is segmented into administrative and assessment parts:

- Part 1: client/patient details. Information to identify the client and any factors that may influence the practitioner’s subsequent management approaches. This includes a summary of the patient’s military career and an identification of any traumatic events or incidents that may have contributed to their current mental health or physical well-being circumstances. A common feature of both MI and spiritual tools discussed above, it is administratively necessary to capture patient details. This process can also be used to provide important contextual information. For example, aligning deployments to particularly traumatic events or locations or identifying multiple deployments to the same region.

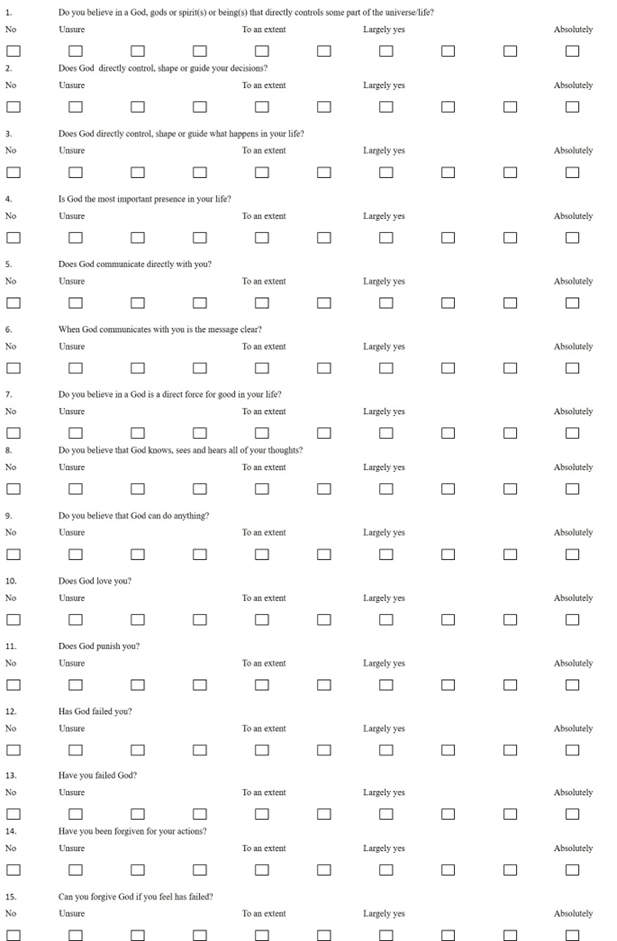

- Part 2: spiritual approaches. Parts 2 and 3 aim to determine the balance between the individual’s spiritual schema and whether it is head- or heart-based. This is not disclosed to the client/patient. Part 2 relates to head spirituality. This is based on 15 questions on a 1–10 Likert scale. Initial/draft questions are subject to further consideration.

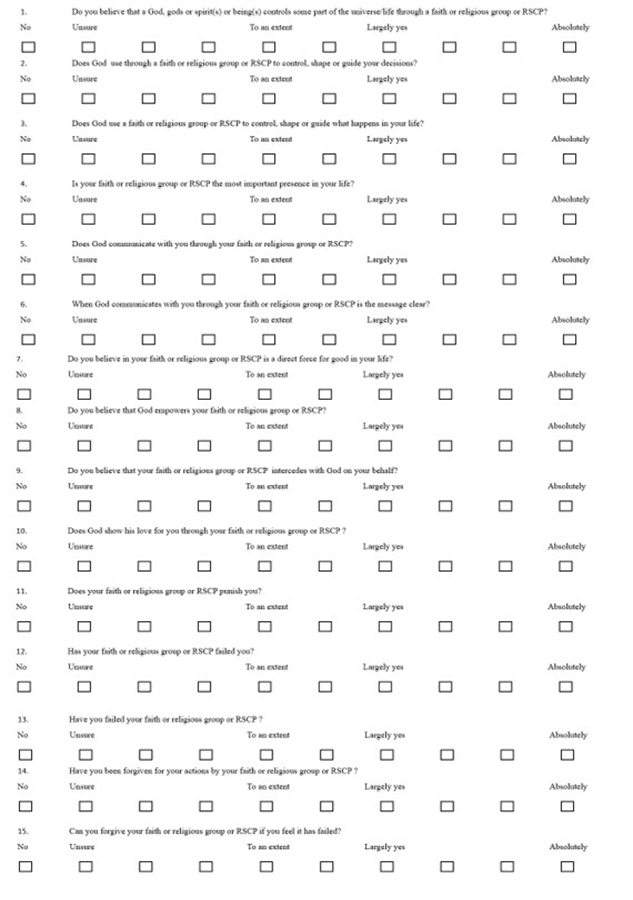

- Part 3: spiritual approaches (continued). As above. Part 3 relates to heart spirituality. This is based on 15 questions on a 1–10 Likert scale. Initial/draft questions are subject to further consideration.

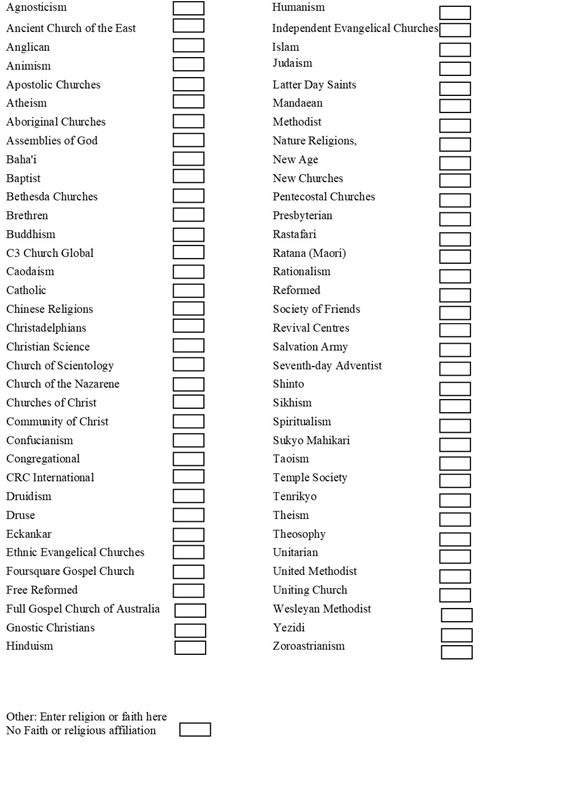

- Part 4: religious/faith affiliation. This part aims to provide the practitioner with an understanding of an individual’s faith or religious affiliation. This area is not generally covered in the spiritual assessment tools described above. However, it is an important guide for the practitioners as they may indicate biases or patterns of thinking that external parties inculcated.

- Part 5: additional comments. Free text space so that individuals may add any additional information they wish to disclose.

- Notes for evaluation. This is only for the practitioner and provides scoring and evaluation calculations, and space to complete a free text evaluation.

Conclusion

The present-day soldier who was brought into a deployed field ambulance on a stretcher will have a much higher chance of survival and full recovery than their peers will at any other time in history. Although weapons lethality is much greater than in any other period in history, so are the tools to remediate the effects of those weapons: helicopters for evacuation, a range of deployable diagnostic medical devices, advanced medicines and medical techniques. There is also a significant shift away from the often-punitive approaches to mental health that were characterised under the heading of shell shock.

Just as commanders will undertake a detailed assessment of the terrain and the enemy before choosing which weapon to use, those seeking to repair unseen wounds, such as MI or SW&I must also undertake such an assessment. To an extent, this is already happening in the fields of mental health and MI, where there is evidence of a range of tested and validated assessment tools. The challenge is that the MI is not a codified discipline with a single definition and a range of approved processes. While this provides opportunities for flexibility in approaching MI, it cannot guarantee consistency. There are also similar tools in the spiritual space, although they still tend to follow a MI model and do not consider some of the fundamental aspects of SW&I that have been discussed to date, such as the singularity of a relationship with a mysterious and unprovable God, or that SW&I can occur before, during and after a traumatic event and not just in the aftermath.

This paper has proposed the use of a SW&IAT-P. This proposed approach allows a supporting RSP to better understand an individual’s spiritual/religious schema to determine whether they have a SW&I because of their defence/military service. The tool also helps the practitioner to understand the nature, causes and extent of the SW&I. In turn, it will also help the practitioner to determine the best management approaches to their circumstances and how to efficiently work with other practitioners, such as psychologists or medical professionals involved in the care. As the SW&IAT-P is a new tool for a new field or discipline and may be a starting point for similar assessments, it must undergo a similar regime to the MIOS to effectively measure SW&Is.

Annex A

Moral and spiritual injury assessment tools

| Moral injury assessment tools | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Outline | Year | Principal contributor |

| Searle-Vance Spiritual Assessment | Based on the Multi-Level Spiritual Assessment (MLSA).25 Seeks to identify the level of spirituality and the pattern and priority of Chaplain care required. | 2007 | Robert Serle C. Garland Vance |

| Moral Injury Events Scale | The Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) is a 9-item scale that assesses actions taken or not taken, or witnessing or being directly impacted by someone else’s actions or inactions that violate deeply held notions of right and wrong. The MIES is anchored broadly to military experiences. | 2013 | William Nash |

| Moral Injury Questionnaire‑Military Version | The Moral Injury Questionnaire‑Military Version (MIQM) is a 20-item measure that assesses exposure to presumptively morally injurious events and feelings associated with those events. The MIQM have primarily has been used in research and not clinical settings. | 2015 | Joseph Currier |

| The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version (MISS-M) | A 45-item measure of MI symptoms for both veterans and serving personnel with diagnosed PTSD. Correlates PTSD severity, depressive symptoms and anxiety within social, spiritual and physical health constructs. | 2018 | Harrold Koenig |

| The Expressions of Moral Injury Scale-Military Version (EMIS-M) | Developed to provide a reliable and valid means for assessing the warning signs of a MI in military populations. Using independent samples of veterans who had served in conflict environments, factor analytic results revealed two distinct factors related to MI expressions directed at both self (9 items) and others (8 items). | 2018 | Joseph Currier |

| Moral Injury Outcome Scale | The Moral Injury Outcome Scale (MIOS) is currently under development by an international consortium Items will address six domains of impact, each with their sub-components: alterations in self-perceptions and moral thinking, social impacts, self-harming and self-sabotaging behaviours, and beliefs about life meaning and purpose. |

2021 | Brett Litz |

| Spiritual assessment tools | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Outline | Year | Principal author |

| Spiritual Well-Being Scale | A 20-item measure that assesses perceptions of spiritual quality of life. The measure has two subscales, Religious Well-Being and Existential Well-Being. | 1982 | Raymond Paloutzian |

| FICA Spiritual History Tool | The FICA Spiritual History Tool is based on four domains of spiritual assessment: the presence of faith, belief or meaning; the importance of spirituality in an individual’s life and the influence that belief system or values has on the person’s health care decision making; the individual’s spiritual Community; and interventions to address spiritual needs. | 1996 | Christina Puchalski |

| Spiritual Assessment Inventory | A 49-item measure of spirituality with five factors: Awareness of God (19 items), disappointment in relationship with God (7 items), realistic acceptance of God (7 items), Grandiosity in relationship with God (7 items), and instability in relationship with God (9 items). | 2002 | Todd Hall |

| Spiritual Coping Strategies scale | The Likert-type SCS scale comprises 20 items, each represented by the frequency and helpfulness of both religious and non-religious coping strategies. | 2003 | Donia R Baldacchino |

| Spirituality Index of Well Being | Defines spirituality as a sense of meaning or purpose from a transcendent source. 12-item instrument measures perceptions of the spiritual quality of life. The scale is divided into two subscales: the self-efficacy subscale and the life-scheme subscale. | 2004 | Timothy Daaleman |

| HOPE Questions | HOPE Questions were developed as a teaching tool to help medical students, residents and practising physicians begin the process of incorporating a spiritual assessment into the medical interview. HOPE Stands for Sources of hope, strength, comfort, meaning, peace, love and connection; O-the role of organised religion for the patient’s P-personal spirituality and practices; E-effects on medical care and end-of-life decisions on their religion. | 2001 | Gowri Anandarejah |

| Spiritual Health and Life-Orientation Measure | Spiritual Health and Life-Orientation Measure (SHALOM) is a 20-item survey that can be used in research and practice. SHALOM has four domains: personal, communal, environmental and transcendental, each of which contains five short statements. | 2010 | John Fisher |

| Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool | The Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool (SDAT) is a 5-item instrument developed to assess unmet spiritual needs in hospitalised elderly patients and to determine the presence of spiritual distress. SDAT has acceptable psychometric properties and appears to be a valid and reliable instrument to assess spiritual distress in elderly hospitalised patients. |

2012 | Stephanie Monod |

| Spiritual Index Scale | The Berg Spiritual Index scale is a guide to a patient-focused, scripted dialogue between a provider and a patient. SI is a self-assessment instrument that investigates the degree of difficulty a person has with eight spiritual injuries. |

2011 | Gary Berg |

| Four FACTs Spiritual Assessment Tool | The Four FACTs Spiritual Assessment Tool combines the LaRocca-Pitts’ Four Fs and the FACT spiritual assessment tool into a single tool. F-Categories: Facts (What are the facts of the patient’s current medical or clinical; Feelings (How does the patient feel about their current medical or clinical situation?); Family/Friends (Whom does the patient consider to be family and friends?); and Faith (What is the patient’s faith, belief, worldview or spiritual practice?). | 2015 | Mark LaRocca-Pitts |

Annex B

Spiritual Wounds and Injuries Assessment Tool-Provisional

The purpose of this tool is to allow your supporting practitioner to better understand your personal spiritual/religious schema to determine whether you have a Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I) as a result of your defence/military service. If so, the tool also helps the practitioner to understand the nature of the SW&I, its causes and its extent. In turn, it will also help the practitioner to determine the best management approaches to your circumstances and how to efficiently work with other practitioners, such as psychologists or medical professionals involved in your care. Please note:

- This assessment is not compulsory for the continued engagement and management with the practitioner(s).

- God, in this sense, refers to a spirit(s) or being(s) you believe control some part of the universe or life and are often worshipped for doing so, or something that represents this spirit or being.

- No value, precedence or authority is attributed to any religion or faith group or lack thereof.

- A Religious/Spiritual Care Practitioner is a multi-faith term that refers to a Priest, Pastor, Imam, etc.

- While the assessment is solely aimed and your care, not all sections need to be completed if the topic or material causes you discomfort.

- This assessment is to be completed by you or your authorised carer/support person (in your presence).

- This assessment form asks for three types of answers.

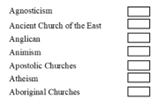

- Single Responses where you cross the answer that most accurately describes your circumstances. For example:

Part 4 – Religious Affiliation

- Scaled answers

- Free text responses to expand on any answer

Part 1 – About you

Name:

Gender:

Date of birth:

Place of birth:

Language spoken at home:

Highest level of education:

Military Service Record (include dates, unit/ship, rank at time of separation):

Please describe any specific incidents or events that you feel may have affected your mental health or general well-being:

- Single Responses where you cross the answer that most accurately describes your circumstances. For example:

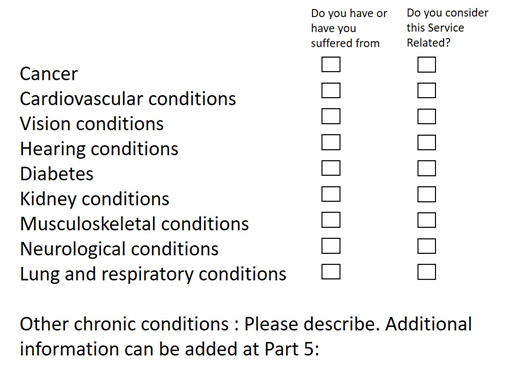

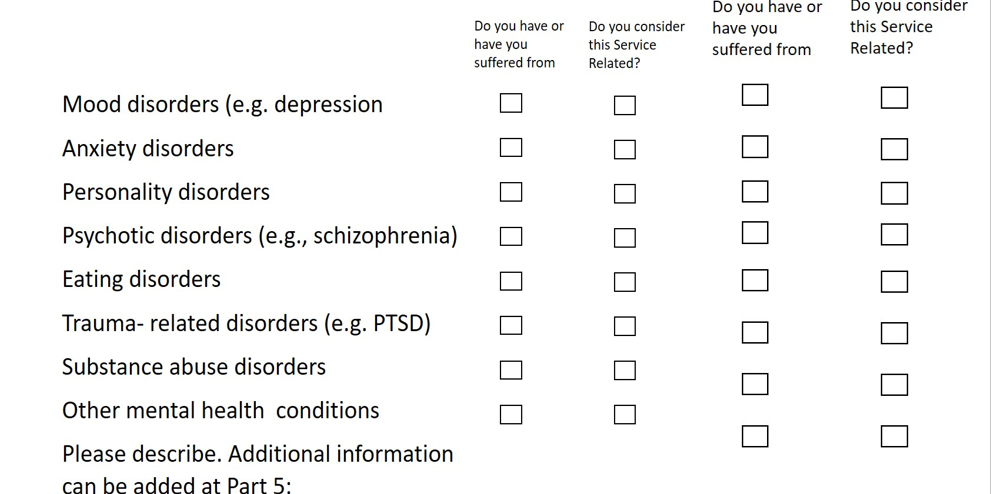

Physical Health Concerns

Mental Health Concerns

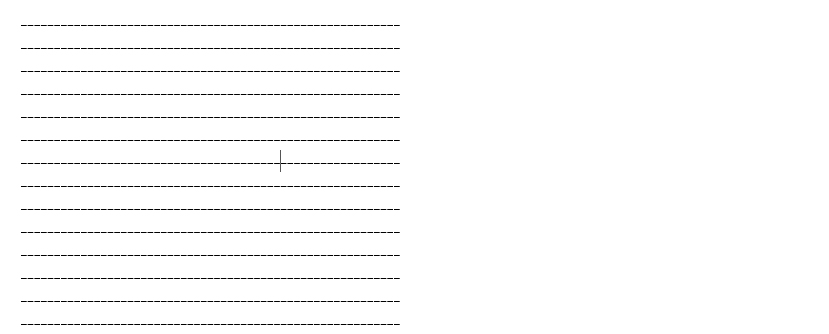

Part 2 – Religious and spiritual approaches

Part 3 – Religious and spiritual approaches (continued)

Part 4 – Religious affiliation

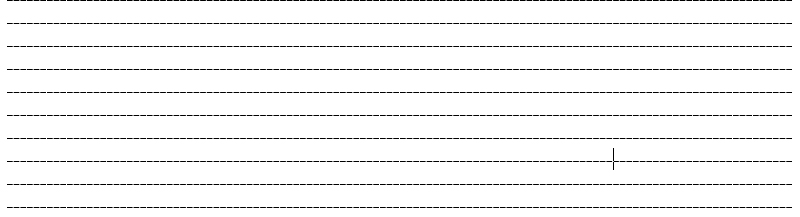

Part 5 – Additional responses

Please add any additional information you wish to disclose.

Notes for evaluation

PRACTIONER USE ONLY

This is only for the practitioner and provides scoring and evaluation calculations and space to complete a free text evaluation.

Once complete, the whole document should be treated as CONFIDENTIAL

Overview

Part 1: client patient details. Information to identify the client and any factors that may influence your later SW&I management approaches.

Part 2: spiritual approaches. Parts 2–3 aim to determine the balance between the individual’s spiritual schema and whether it is head or heart-based. This is not disclosed to the client/patient. Part 2 relates to head spirituality. This is based on 15 questions on a 1–10 Likert scale. Initial/draft questions are subject to further consideration.

Part 3: spiritual approaches (continued). As above. Part 3 relates to heart spirituality. This is based on 15 questions on a 1–10 Likert scale. Initial/draft questions are subject to further consideration.

Part 4: religious/faith affiliation. This part aims to give the practitioner an understanding of what faith or religious grouping an individual may feel affiliated with.

Part 5: additional comments. Free text space so that individuals may add any additional information they wish to disclose.

Scoring

1. Each answer is given a numerical value.

2. But each line should only have one rating.

3. Score Part Two by adding the total of each line.

4. Score Part Three by adding the total of each line

Interpretation

The interpretation of SW&IAT-P is based on the scoring of Parts 2 and 3 but is also shaped by the practitioner’s observations and understanding of the client/patient. Generally,

- Higher scores responses on Part 2 of the SW&IAT-P may indicate a heart-based spiritual approach by the individual. This may require the RSP practitioner to utilise more spiritual counselling tools that engage with the client/patients to work through issues and responses. In accordance with World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) 2019/2021. This may include establishing of relationship/engagement with another, hearing the story and enabling pastoral conversation in which spiritual well-being and healing may be nurtured, supported and companioning persons confronted with profound human issues of death and dying, loss, meaning and aloneness. Predominantly a ‘ministry of presence and support’ pastoral counselling or education (ICD code 96087-00) [Major heading: 1869].

- Higher scored responses on Part 3 of the SW&IAT-P may indicate a head-based spirituality approach by the individual. Accordingly, RSPs may draw from the doctrine, dogma, religious ceremony and ritual and the context of religious philosophy and theology. This intervention contains the pastoral expressions of informal prayer and ritual for individuals or small groups, and the public and more formal expressions of worship, including Eucharist and other services, for faith communities and others. Elements of this intervention may include: ‘(a) private prayer and devotion’, bedside ‘Communion’ and ‘Anointing’ services, and other sacrament and ritual expressions; (b) public ministry — Eucharist/Ministry of the Word, funerals, memorials, seasonal and occasional services (ICD code 96109-01) [Major heading: 1873] While one approach may lead, given the results of the SW&IAT-P, RSP will need to be skilled in both areas as a blended approach is more than likely to be necessary.