Abstract

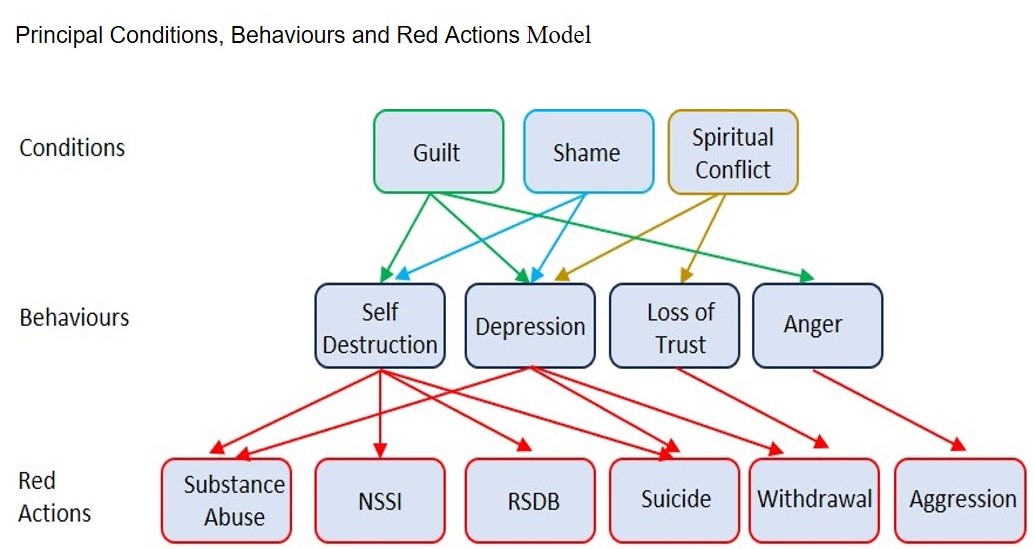

The mauling that some veterans suffer as a result of issues such as shame, anger, self-abuse and depression are very real, lasting and painful aspects of their lives. For a Religious/Spiritual Practitioner (RSP), or indeed any treating practitioner, to make a meaningful contribution towards treating a Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I) they must determine how this condition presents. The paper follows previous arguments by the author that a SW&I starts with a break in an individual’s relationship with their concept of God. The manifestation of the SW&I may then follow a pathway such as the Principal Conditions, Behaviours and Red Actions Model (PCB&RA Model).

This paper acknowledges that, in some respects, the behaviours of a SW&I may seem very similar to many mental health or general wellbeing issues. Indeed, in many cases, the treatment of SW&I may utilise similar treatments and management approaches to moral injury (MI) or mental illnesses. However, the elements discussed in the PCB&RA Model are all predicated on seeing these conditions, behaviours and actions through a spiritual lens.

Keywords: SW&I, spirit(ual, uality), military, wound, defence(se), veteran

Introduction

St Longinus was a Roman Centurion who commanded the crucifixion party at Golgotha, where Jesus died. According to the Acts of Pilate in the Gospel of Nicodemus, he purportedly pierced Jesus’ side with his spear either to confirm that he was dead or perhaps to hasten his death.1 As a result, Jesus then,

Yielded up the ghost. And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from top to bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent, And the graves were opened, and many bodies of the saints which slept arose, And came out of the graves after his Resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many. Now when the centurion, and they that were with him, watching Jesus, saw the earthquake and those things that were done, they feared greatly, saying, ‘Truly this was the Son of God’. Matthew 27:54 (King James Version).2

Although there is an argument that the actions of St Longinus were part of a much larger spiritual narrative, there is no doubt that he feared greatly at the time and perhaps suffered for a long time afterwards. The author has argued that due to his actions that day, St Longinus suffered a Spiritual Wound and Injury (SW&I).3 This was described as like being ‘mauled by a lion every night, only to have his body restored during the day in preparation for another night’s agony’.4 This metaphorical mauling would seem very much like the doubt, shame, guilt, and other issues afflict any veteran whose experiences with trauma have caused a break or change in their relationship with God and, in turn, led to a SW&I.

This paper aims to highlight how a SW&I may present to help spiritual, religious, medical, psychological and other practitioners manage the spiritual health of veterans who have experienced trauma. As previously argued, a SW&I has different causes and needs different approaches to a MI or a mental health illness.5 It is therefore critically important that treating practitioners of whatever ilk can recognise and understand the potential symptoms or presentations of an SW&I.

Principal Conditions, Behaviours and Red Actions Model

In some respects, the behaviours of a SW&I may be very similar to many mental health or general wellbeing issues. Similar is not, however, the same. There are three important issues to note:

- Cause. A SW&I occurs as a result of a break in the relationship between a veteran and their concept of God or a Divine figure. As a result, the individual displays different types of undesirable behaviours. While a physical event such as a Thin Place Event (TPE) may be the initiating incident, the source or cause of the SW&I and how it is presented may be difficult to prove as it will relate to how the individual perceives God.5

- This is a fundamentally different circumstance to a MI or mental health and general wellbeing incident, where a traumatic event such as a potentially morally injurious event (PMIE) will leave a series of medical, moral and scientific indicators. While the actual event—TPE or PMIE—may be the same, the individual’s relationship is not to another human or society’s rules, laws and morals. It is a relationship to an unmeasurable and vapours concept of a supreme guiding being or entity. Engagement with this entity will be either through human facilitation by a priest, minister, rabbi or some other Religious and Spiritual Practitioner (Head Spirituality) on behalf and guided by God or directly through some form of seen, felt or heard individual interaction with God (Heart Spirituality).5

- Continuance. Accordingly, the subsequent course and treatment of the SW&I will then follow these circumstances. A Religious/Spiritual Practitioner (RSP) working with a veteran suffering from a SW&I will follow that individual’s journey through each stage of the SW&I Transition Path Model.5 Importantly, this model acknowledges that a SW&I is more than just the aftermath presentation and includes recognising predisposing factors and the specific nature of the event.

- Collegiate. Equally important is that although a SW&I may be the specific focus of an appropriately trained and accredited RSCP, there may be significant involvement from medical and psychological practitioners. This is because a traumatic event is unlikely to leave a single scar, and there may be a multiplicity of physical, spiritual moral injuries.

That a condition such as shame or guilt may cause an individual to lose faith in God is not the SW&I; it is the effect that this loss of faith has on some individual’s mental health and overall wellbeing and how that might present in behaviours such as substance abuse, depression or anger. Not every individual has a religious or spiritual belief system. For those that do, however, threats to this schema can significantly affect their lives. Although further study and analysis are required, this paper argues that some presentations of a SW&I can be modelled based on Principal Conditions, Behaviours and Red Actions (PCB&RA Model).

Conditions

The presentation of a SW&I lies in the relationship between a condition and behaviours. For this discussion, the following definition of a condition will be used:

- A logical antecedent on which a conclusion is dependent or an empirical antecedent on which an event or state is dependent. A necessary condition is one without which the idea would not logically follow, or the event would not occur. A sufficient condition is one that directly entails a particular conclusion or that has the power to produce a particular event regardless of other conditions.6

- This paper will examine three conditions based on Jeremy Jinkerson’s description of MI: Guilt, shame and spiritual or existential conflict.7

Figure 1: Principal Conditions, Behaviors and Red Actions Model

Condition 1: Guilt

Guilt is an ancient and powerful force in humanity that crosses most boundaries of culture and religion. Feelings of guilt can be powerful and the basis for many behaviours. Many veterans carry significant feelings of guilt, which do not necessarily fade after they leave the military. In a British Journal of Clinical Psychology study, trauma-related guilt significantly predicted DSM-5 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity among US veterans and military members.8

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines guilt as ‘a self-conscious emotion characterised by a painful appraisal of having done (or thought) something that is wrong and often by a readiness to take action designed to undo or mitigate this wrong’.9 Within this definition, the word ‘emotion’ implies that the perception of guilt may not be necessarily based on what a person, be it the individual, a leader or even a RSCP, did, but instead on a feeling or personal interpretation of what they thought they did. While the nature of the guilt is conceptualised as remorse, regret or self-condemnation in this way, it is most often linked to an event.10 Granted, ‘wrong’ is a subjective term; however, it indicates that the action or event has been judged somehow and found to disagree with the standards of an individual, a belief system or a community. A ‘painful appraisal’ indicates that the perpetrator pauses to think deeply about the event. Furthermore, thinking deeply about guilt is also ‘an uncomfortable, even viscerally disturbing condition’.11

Spiritual legacy

Which behaviour a veteran demonstrates based on these conditions will be significantly influenced by their spiritual predisposition and background. One young soldier who had shot two insurgents wondered whether God still loved him and yet does not appear to have felt any sense of legal or moral guilt over his actions; instead, he felt guilty before God.12

Most faiths have a rich language and dogma when it comes to guilt. It also has a powerful spiritual dimension and the relationship along a guilt-sin-punishment-redemption-forgiveness spectrum, a feature of many religions and faith groups. Exodus 34:7 states that the Lord ‘does not leave the guilty unpunished’.2 Similarly, the Qur’an states that ‘Allah loveth not the impious and guilty’ (Al-Baqarah, Q.2:276), and the Hindu Vedas proclaim, ‘Let me not suffer for the guilt of others!’.13 It is interesting to note that in all three examples, there is a real sense of guilt as a feeling that is to be feared and dreaded. The intensity of this fear and dread is such that people may display some behaviours that they use to either express or, conversely, numb and repress their feelings.

At the same time, guilt can also be adaptive and lead to spiritual growth. A response to a transgression might motivate the person to take reparative action (e.g., going to confession, asking God for forgiveness), and this may then relieve the distress associated with feelings of guilt and a stronger conceptualisation of other aspects of the person’s life.14

Familial guilt

A veteran’s family is not immune to the impact and influence of spiritual guilt. Veteran 20210503 was an Australian Army medic deployed on several overseas missions.15 After their return from another deployment, their partner killed themselves. This veteran felt genuine guilt over this event and stated that,

I should be locked up with all of the Godless rapists and murderers. Where was my loyalty to the one person who had stood by me since I was eight? I was so wrapped up in my career and wanted to show everyone that I was good enough to be in the Army.

Condition 2: Shame

Shame is a curious thing for veterans. On the one hand, every veteran can share vaguely humorous stories of a drill or physical training instructor who publicly used their inability to perform a given task to the same standard as the group as a humorous example or a teaching point. Sadly, there are stories, such as the British Army instructor who reduced a female recruit to tears during bayonet practice with a vicious tirade on how she was not a ‘killer’.16 In both cases, shame is used almost as a training tool designed to punish and correct a soldier whose performance has not lived up to or met the group’s standards. It can also be used by the group members against another member to punish or correct behaviour and performance they feel fails to meet the required social standard of their group.

Shame is a powerful influence on veterans’ mental health and overall wellbeing. Shame is a principal factor of MI. There is also credible evidence pointing to shame as being one of the main contributors to the development of PTSD, as it has a high-level influence on suicidal ideation that reduces the veteran’s capacity or willingness to seek help.17 Shame also has many possible spiritual aspects. It was one of the first human emotions expressed in The Bible. In Genesis, chapters 2 and 3 talk of Adam and Eve’s shame at being naked and hiding from the Lord after eating from the ‘Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil’.2 A spiritually vulnerable veteran can either be ashamed of their behaviour in front of God and feel that makes them unlovable in the eyes of their creator or conversely ashamed they ever believed in a God who would ‘let bad things happen’ to their friends or the innocent.

In many respects, it is often difficult to separate the concept of shame from its twin emotion, guilt. The APA Dictionary highlights this by noting that guilt is ‘distinct from shame, in which there is the additional strong fear of one’s deeds being publicly exposed to judgment or ridicule’.9 The APA separately discusses shame in more detail, saying it is a ‘highly unpleasant self-conscious emotion arising from the sense of there being something dishonourable, immodest or indecorous in one’s own conduct or circumstances’.18

Elements

There are many general concepts about shame as a condition of SW&I that are relevant:

- Unpleasant and self-conscious. Ultimately, shame develops when a person’s ‘dishonourable, immodest or indecorous actions’ are exposed to some form of public view and then internalised to become evidence of themselves as being intrinsically bad. As one author says, ‘I’m a failure, or I’m a monster’.8 Shame can have a single or a series of starting points or TPE. There may be a definable moment or a series of moments leading to a growing awareness wherein the individual realises they have done something shameful.

- Internal and external. Shame has a distinct pattern, Awareness, Reinforcement and Acceptance (ARA Pattern). The individual must be aware that they have committed what might be a shameful action. The existence of shame is undoubtedly unpleasant, but it indicates that the person has a level of self-consciousness. Sometimes referred to as ‘internal shame’, it is where the individual devalues themselves in their own eyes against the norms of the group. The individual’s sense of shame is reinforced when it receives external validation when they perceive others look down on them and see them as inferior or inadequate in some way. As the psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman notes, ‘it is, an acutely self-conscious state in which the self is “split”, imagining the self in the eyes of the other’.19 The depth and extent to which internal or external shame penetrates and is accepted, therefore, depends on the degree of acceptance by the individual. An individual cannot be forced into a state of shame. Many people have committed terrible acts and feel no sense of guilt or shame for their actions; however, those individuals in Herman’s state of acute self-consciousness often accept that both their actions were shameful and their perception of others’ feelings towards them is accurate.

- Evolutionary influence. Shame may have developed as a necessary survival tool. Throughout human history, group membership and adherence to specific codes of group behaviour and practice were necessary for survival. Shame may have evolved as an effective signal to non-conforming individuals and those who may think of straying from the group path that they posed a social threat. The Holy books, such as The Bible, foster this idea. The books of the Pentateuch (Torah), for example, are primarily devoted to the establishment of laws (and penalties) that are devoted to establishing an identity and structure for the Israelites after they left Egypt. As such, shame, social exclusion and rejection may have evolved to ensure the larger group’s survival.20 Given the team and group nature of the environments most veterans come from, this aspect of culture may also be a significant factor.

Spiritually, shame as a condition of SW&I has two possible aspects. The first is that the individual is ashamed of God. For example, an Australian Army Officer who committed a negligent discharge blamed God for allowing him to be ‘so stupid’. In another Australian example, an Army logistician whose speciality meant he could not be deployed responded to a well-meaning civilian compliment, ‘Thank you for your service,’ with, ‘God didn’t let me serve, so don’t thank me’.12 Closely linked is the idea that an individual may feel ashamed if they believed an omnipotent God could have stopped them from being in a particular situation and being shamed or exposed to potential shame. As one US veteran from the Vietnam War later wrote, ‘I cannot believe in a God who would permit what I have just lived through’.21

In some cases, an individual may feel they have offended, angered or disappointed God and are ashamed accordingly. An example of this can be seen in the confession of one US Special Forces operator in Cambodia during the Vietnam War. He would vomit for hours and ‘beg God to forgive us for what we are doing’.22 To these veterans, God is a very real and all-knowing feature of their lives, and when they feel they have failed to live up to their expectations of what God thinks, they feel ashamed. Another example is the US soldier who wrote of his experiences in Afghanistan and how God knew he was an ‘imposter’ and that he could not ‘fool God’.23

Condition 3: Spiritual or existential conflict

Several commentators suggest that a spiritual or existential crisis or conflict may occur in the aftermath of a MI. These authors include Drescher et al.,24 Jinkerson7 and Brémault-Phillips et al.25 Although highly credible authors, this is an example of the poor use of spiritual concepts, language and terminology that is common in much of the broader MI-based discussion on spirituality.26 At no point do any of these or other authors explain the term spiritual or existential conflict. It appears to be an assumption on their behalf that this term is understood or common.

Likewise, it is important to remember that SW&I is not limited to the aftermath of an event or that it occurs concurrently or following a MI. As discussed, a PMIE and TPE can occur concurrently or separately. Regardless, a spiritual or existential conflict needs further exploration if its impact on a veteran’s SW&I is to be considered further.

The terms spiritual and existential need to be separated. Although a convenient conflation, such as spirituality and MI, these terms have separate meanings. An existential conflict or crisis is any psychological or moral crisis that causes an individual to ask ‘fundamental questions about human existence’.27 Spirituality essentially rests on the existence of a God or gods or some other universal guiding force. An individual’s existential conflict relates to their experience with humanity and does not necessarily include this Divine guiding force. Thus, an existential crisis/conflict sits in the domain of MI, and a spiritual crisis/conflict relates to SW&I.

Cognitive dissonance

The idea that a spiritual conflict relates to an individual’s conflict with their beliefs implies that they have some existing religious or spiritual belief that underpins or shapes their thinking. Such belief may be unformed and lacking detail or highly developed and mature. The conflict comes when an event, a TPE, occurs that causes them to ask why and what. Shay’s question, why ‘in an ethical universe run by a just, loving and all-powerful God…’ is a good example of this.28 Such questions then prompt that person to consider, ‘What does this mean for me?’ Asking that question does not indicate a lack of faith or belief but a perfectly rational response to an event that has created a degree of dissonance or confusion between the truth and what people want to believe. In 2009, Litz argued that, in a MI context, such circumstances cause ‘dissonance and conflict because it violates assumptions and beliefs about right and wrong and personal goodness’.29

Psychologically, this is referred to as cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance is the state of psychological discomfort that occurs when an individual is confronted with an unequivocal truth that contradicts a strongly held previous belief.30 Psychologist Leon Festinger first proposed the theory behind this in his 1957 book, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Festinger argued that individuals experience discomfort when confronted by conflicting beliefs or when their actions contradict their beliefs. As such, their goal is to reduce dissonance to relieve their discomfort. The resolution process is known as the ‘principle of cognitive consistency’. It may entail either seeking out what is true or avoiding the situation and its circumstances.31

Cognitive dissonance is not an automatic or instinctive reaction for individuals facing circumstances that may challenge previous beliefs.32 Some individuals may have a higher tolerance to uncertainty and inconsistency and may, therefore, experience a reduced cognitive dissonance, as opposed to those who require consistency. It can be more prevalent in the case of those who have made an ‘irrevocable commitment’. This might be a contract, agreement vow or some other form of significant undertaking to do something or act in a certain way. This is most clearly relevant to most military organisations requiring individuals to sign or agree to some form of oath or attestation upon enlistment. Such a circumstance resonates with those whose spirituality may have a heart basis and is more aligned with the doctrines and commandments of a faith group.33

Behaviours

The previous set of conditions are the gateways for the behaviours that affect some individuals’ mental health and overall wellbeing and how this might present in harmful behaviours. A behaviour is ‘an organism’s activities in response to external or internal stimuli, including objectively observable activities, introspectively observable activities (…covert behaviour), and nonconscious processes’.34 The SW&I concept is that spiritual wounds and injuries result from an antecedent condition and subsequent behaviour. Of course, it will not necessarily be neatly separated, and it is more than likely that aspects overlap and link. Likewise, many behaviours might be included in this area; however, these can be grouped under three main categories. Each term in these categories is shared across the medical and psychological spectrum, although only the potential head and heart spiritual aspects will be considered.

Behaviour 1: Self-destruction/sabotage

A typical behaviour that spans MI and mental health issues, such as PTSD and SW&I, is when a veteran behaves in a way that is harmful or potentially harmful to themselves or others. Humans are not predisposed towards self-harm; their base instincts lie in self-preservation. Nevertheless, many veterans may undertake a range of behaviours that run against this ancient instinct. These behaviours include Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI), Reckless and Self-Destructive Behaviours (RSDB), suicidal ideation or death by suicide.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

NSSI is also known as intentional self-harm, self-injury, self-mutilative behaviour or parasuicide. It refers to individuals purposefully engaging in acts that cause physical pain or harm to themselves. Burke argues that ‘guilt is intensely painful, and a person thus stricken will seek a cure at any cost… the cure will occur only through some form of “victimage”, for someone or something must suffer if the world is to be set right’.35

Typically, NSSI may include cutting, burning, head-banging and severe scratching.36 One study of US veterans suggested that 22% of veterans will engage in NSSI at some stage.37 A supporting Scottish study noted of its base of 57 000 veterans that the highest risk of NSSI was in veterans with the shortest service, especially those who did not complete training or minimum engagement. Older birth cohorts and those who had served longer were at reduced risk.38

The causes and treatment of NSSI are subject to a growing body of secular scholarship. From the spiritual perspective, NSSI may be an act of mortification. ‘Mortification of the flesh’ refers to an act or acts by an individual to mortify, deaden or atone for a sin or a sinful nature. It is seen as a part of the process of sanctification and redemption. It has a scriptural Hebrew Bible in Zechariah 13:6 and 1 Kings 18:28–29 and the New Testament in Romans 8:13 and Colossians 3:5.2 Historically, mortifying the flesh was a physical action such as flagellation or wearing hair shirts or chains.

There is evidence of self-mortification experiences related to the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington. While not further specified, Cheree Carlson and Hocking argue that veterans visiting the memorial undertake minor acts of mortification, an act that,

requires self-abnegation. The individual has internalised the imperfections and can obtain purification only through some private punishment. Although the victims differ, the result is the same. Guilt is purged, and order is restored. Unfortunately, the redeemed state is brief, for there is always something wrong in the world, always a new source of guilt.39

Reckless and self-destructive behaviours (RSDB)

This self-abnegation or self-denial may also manifest as self-destructive behaviour, such as veterans being unwilling to seek spiritual care as they feel either that they are not worthy or that there is a benevolent God able to help. This may also cause them to be unwilling to seek help in another medical or psychological area. RSDB typically presents as self-initiated actions such as dangerous alcohol or drug use, drunk driving, gambling and aggression/anger.40 On one level, it is seen as a symptom of PTSD, with a 2017 survey on behalf of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) finding that 74.4% of a sample of veterans displayed RSDB-related acts. Of the sample, 61.3% engaged in multiple forms of RSDB. The most common behaviours include alcohol/drug abuse (42.8%), driving while intoxicated (29.4%), gambling (24.7%) and aggression (23.1%).41 RDSB has also been similarly linked to MI.42

Although there is limited information and analysis regarding RSDB and spirituality, it is likely that given the shared linkages to PTSD and MI, there would be similar spiritual damage. Accordingly, as a SW&I, RSDB may display in a very similar way. However, the critical issue that will fundamentally shape how this is managed and approached relates to the individual’s relationship with God. For example, a condition such as shame may lead to behaviours such as excessive drinking or drug abuse. This may include an individual with a heart-based spirituality trying to drown out or deaden the voice of God. A shame condition may be linked to Red Actions or behaviour, such as drunk driving or aggression may relate to an individual who rejects higher authority and the rules of society. It may also be a case where an individual is ‘testing’ God to prompt a reaction or ‘proving’ that God does not exist by tempting fate.

Suicide

It is a sad fact that suicidal ideation and death by suicide are a growing trend internationally among veterans. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) annual suicide monitoring report revealed that at least 1600 serving and ex-serving ADF members died by suicide between 1997 and 2020. There were also a further 79 deaths by suicide in 2020.43 Such was the scale of this issue that Australia created a Royal Commission in 2021 with Letters Patent that directed an investigation into, among other areas, ‘systemic issues and any common themes among defence and veteran deaths by suicide, or defence members and veterans who have other lived experience of suicide behaviour or risk factors (including attempted or contemplated suicide, feelings of suicide or poor mental health outcomes)’.43

Interestingly, nothing to date in the Royal Commission’s reports or material mentions religion or spirituality. Some submissions have been from individuals and organisations with a faith agenda, but this has yet to translate into recommendations or proposed actions.43

Most faiths and religions do not support suicidal acts, including assisted suicide. In the case of Judaism and Christianity, while there is no explicit biblical prohibition on suicide, rabbinic authorities derived a prohibition that was later taken on by Christian theologians from the verse in Genesis 9:5, ‘And surely your blood of your lives, will I require’.2 Islam is more proscriptive, and in Chapter 4, Verse 30 of the Qur’an, God says: ‘And kill not yourselves. Surely, Allah is Merciful to you’.44 At the same time, there is significant evidence that religious and spiritual beliefs and counselling can positively reduce the provenance of suicidal action. Important work in this area includes Smigelsky,45 Carey and Hodgson,46 and Brandt.47

Despite this and the various spiritual and religious conventions and prohibitions, many veterans with religious or spiritual beliefs will take their lives. This area will hopefully be addressed in the Royal Commission’s final report and deserves much more specific study and analysis. Meanwhile, there are likely to be some conditions and behaviours that might indicate or present as suicide ideation. For example,

- Failure and guilt. A condition such as guilt may lead to veterans developing a sense of failure and worthlessness and believing their only release is extreme punishment. Intense shame may cause veterans to withdraw and conceal physically or through numbing substance abuse.

- Withdrawal and guilt. A sense of guilt often leads to withdrawal, The ultimate withdrawal being suicide. For some veterans, that may even be the return to a loving God/father who will protect them.

Behaviour 2: Anger

A DVA publication discussing veterans and anger uses a case study of a twice-deployed veteran named Darren. After returning from the deployments left the Army and commenced a downward spiritual, which involved excessive drinking, physical abuse of his spouse and others, and depression.48 The case study described that:

Darren struggled on his own and found himself reacting to the slightest things. People in the street who looked at him the ‘wrong way’ or walked too slowly, anyone really was at risk. Risky, it was because Darren had no doubt of his strength and how quickly his anger could appear like a flash out of nowhere. He was terrified that the two made a deadly combination.48

The trope of the angry veteran spans several themes. It often relates to the ‘Government’ and its perceived failures regarding conflict and general actions. It is especially prevalent in areas of veterans’ affairs and access to benefits. For example, a 2023 ABC News Story was headlined, ‘Veterans say they are white hot with anger, as new data shows some waiting times blowing out at the Department of Veterans Affairs’.49 Phoenix Australia notes that statistics from the Australian Transition and Wellbeing Program show that 31% of veterans and 16% of current-serving military personnel experience anger at a problematic level.50 As a reference point, it notes that among those impacted by disasters, such as bushfires, 10% experience problematic anger. Findings such as these show us that anger is a significant issue that needs attention—other studies, such as Varker et al.,51 show similar results.

The APA Dictionary defines anger as ‘an emotion characterised by tension and hostility arising from frustration, real or imagined injury by another, or perceived injustice’.52 The term emotion is important here. There is no suggestion of irrationality behind the veterans’ feelings but, rather, that it is a deeper, almost primal aspect of their behaviour. Some of this relates to how they feel society perceives them.53 The treatment of Vietnam Veterans in Australia and the US is a case in point here. Part of the source of the anger also comes from a common feeling among veterans that no one’ understands what we went through and that those who seek to help cannot, as “If you’ve never been there, you wouldn’t understand’.54 There is also substantial evidence pointing to anger as a symptom or comorbidity of PTSD.55 Sadly, longitudinal assessment has also provided evidence that anger and PTSD can be a catalytic precursor to suicidal actions.53

From a spiritual perspective, there needs to be more research to establish the nature of the relationship between spirituality and anger. Given the previous discussion in this thesis, however, it is likely that the conditions and behaviours of a SW&I may present as follows:

- Spiritual conflict – Anger at God. Simply put, the individual feels that God failed them by not acting in a way they feel met their needs or desires. Their spiritual heart perceives God failed to protect them, a mate or the innocent. This sense that God failed them when they had previously placed trust, faith and belief in the Divine can be overwhelming and create significant anger and possibly aggression issues—especially when exacerbated by Red Actions such as excessive and dangerous consumption and use of alcohol or drugs.

- Shame – Anger at self. One result of this conflict may be that the individual may feel stupid or immature at having ever believed in God and any sense of power or benevolence they could rely upon. They may also feel anger and a sense of shame and embarrassment for having thought or trusted that God would let him serve. The condition of shame and the behaviour of anger in this circumstance may present rejection of authority, withdrawal and avoidance.

- Guilt – Anger at God’s representatives. The Australian company commander in the Vietnam War thought the Methodist padre attached to his battalion was ‘hypocritical’ because he spoke of killing and forgiveness in the same breadth.56 Likewise, a civilian RSCP, when asked how they would work with a veteran who had killed someone, replied that they would make the veteran ‘spend the rest of his life on his knees begging forgiveness for the heinous sin they have committed…’ would be judged as guilty of hypocritical.57 This would have undoubtedly turned the individual away from the church and caused them to reject any further spiritual support.

Behaviour 3: Depression

Damien Thomlinson was an Australian Army infantryman, a veteran of tours in East Timor, the South Pacific and Afghanistan. He lost both legs in an Improvised Explosive Devise (IED) explosion in 2009. Reflecting on his depression following life after the military, he said,

You know, in the military, you’re proud of how you look; you’re proud of how you served. And all of a sudden, I couldn’t serve in the way that I wanted to, as a commando in the special forces. That was it. That was my job, and to me, my identity… The enemies that I faced when I got home were a lot worse than the enemies that I faced on the battlefield, you know? For the simple fact that you’re not ready for it. When you come back, it’s the shock factor, thinking: ‘Wow, I didn’t really expect this. Is it me?’58

For many veterans, depression is a real and palpable feeling that can dominate their lives. While it is gaining growing understanding within the community, it is a common condition among veterans across many conflicts. In a 2007 study, veterans from the Korean War displayed higher levels of depression over 50 years after the war.59 Similar findings can be seen in Australian Gulf War veterans, with the prevalence of depression at 9.7% against 7.7% in a comparison group. Importantly, veterans reported slightly more severe symptoms (and were more likely to have been dispensed antidepressant medication).60 In 2022, the AIHW assessed that 12% of males who ever served in the ADF reported having had depression or feeling depressed. Those who had ever served in the ADF were almost twice as likely to report having an anxiety-related disorder as those who had never served (21% compared with 11%).61

The APA Dictionary defines depression as ‘a negative affective state, ranging from unhappiness and discontent to an extreme feeling of sadness, pessimism and despondency that interferes with daily life’.62 Depression can present in various ways: feeling sad or having a depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed, trouble sleeping or sleeping too much, feeling worthless or guilty and ultimately, thoughts of death.

From a spiritual perspective, depressive symptoms and behaviour may be linked to cognitive dissonance when an individual finds their faith in God or a Divine figure is threatened or broken. In this sense, the conditions and behaviours of a SW&I may present as follows:

- Guilt – Depressed at failing God. The soldier who felt God did not love him as he had killed two men was demonstrating a guilty condition and depressive behaviour. How this specifically manifested in terms of his behavioural change is unknown, but the individual felt that he had done the ‘wrong thing’ in the eyes of God. As a result, he reached out literally and deliberately to the first RSCP (an Army padre) that passed by.

- Spiritual conflict – Depressed now knowing that God is not real. The result of a TPE that may cause an individual to perceive (heart of head) that God is not real must be devastating for those with any faith or spiritual background. Whether suddenly or over incidents or years, concerns regarding the existence and nature of God may make an individual feel that a foundational aspect of their lives is missing. They may, in turn, seek ways to withdraw so as not to be placed in a position to seek Divine help or try to manage depression through Red Actions such as various forms of substance abuse.

Behaviour 4: Loss of trust

One of the first areas to be included in studies of MI was the suffering of soldiers whose leadership, political, military and moral had failed them. This included battlefield blunders, tactical errors and cases where soldiers felt they had been lied to and deliberately misled. As Litz et al. noted in 2009, ‘among those affected by MI, the capacity for trust is believed to be lost, impaired or even destroyed’.29

The importance of trust in operational circumstances cannot be overstated. This military service dynamic pushes the issue of trust to the forefront and has no limits. Accordingly, policy and culture seek to ensure individual and organisational safety is inherently dependent on trust between soldiers to adhere to a shared culture of accepted practices, principles, values, beliefs and behaviour.63 Within an Australian context, this is exemplified by the universally accepted statement that ‘you don’t let your mates down’.64 When trust is abused, it can significantly hamper access to social capital and supportive services, contributing to a downward spiral of increasing social isolation and difficulty accessing vital services.63

Spiritually, when an individual experience experiences a TPE, their perception of God may change. Their Spiritual Arc may grow, be restored or degrade.5 Depending on the nature of the TPE, a degrading arc may lead some individuals to a crisis of faith or spiritual conflict in which their perception of God is significantly sullied to the point where they may feel that God does not exist. The state of cognitive dissonance that this engenders can be overwhelming, particularly if they have preconditioning factors such as a long faith history or close familial ties to a church or religious group.

In some cases, trauma may lead veterans to believe that God has betrayed their trust’. As such, a TPE becomes the catalyst for all the evil in the world that God has failed. When an individual experiences this and the true evil it represents, it provides an enormous challenge for veterans who were taught to believe in a good, caring and all-powerful God. For those who believe that God is a being who brings order from this may create a sense of invulnerability and continuity that is shattered by traumatic events. In the face of such hardship, to make sense of the universe, some veterans may conclude that God can no longer be viewed as all-powerful, completely loving and involved in the salvation of humanity. When the absence of God is experienced most extremely, some views of God may no longer be possible, and religious teachings may be seen as good theories, although essentially meaningless. Such a crisis can test those with the deepest and firmest faiths. This includes supporting RSCP. One US Army Chaplain in Iraq in 2003 membered thinking that,

I couldn’t stand to hear that phrase any longer—’God was watching over me….’ He wasn’t watching over the good men I knew in Iraq. Faith was the centre of my life, yet it failed to explain why I came home, and those soldiers did not. The phrase was a Christian nicety, a cliché that, when put to the test, didn’t fit reality… What kind of God would allow people to sink to the depths we here in this world had sunk?65

In this sense, the conditions and behaviours of a SW&I with a loss of trust will principally result in withdrawal. Withdrawal in this circumstance may have some different aspects.

- Withdrawal from spirituality. Depending on the individual’s background, this might range from no longer attending religious services to avoiding anyone or anything connected to their spiritual path. The likely thinking is that if they cannot trust God, who can trust his representatives on earth? The danger is that it can altogether remove the veteran from meaningful engagement and support.

- Withdrawal from society. Linked to this is a withdrawal from society in general. Like a spiritual withdrawal, this removes the veteran from human contact to one degree or another. In this case, the failure of trust is extreme, and the veteran rejects both the spiritual and secular world. An aspect of this is that veterans may also reject the authority of secular leaders, military or civilian, as they are symbols of the Divine leadership, which they feel is no longer trust.

- Withdrawal from treatment. If a veteran has withdrawn from a previous spiritual scheme, it is unlikely that they will seek or respond to the spiritual aspect of treatment for their SW&I. This may also manifest in distrusting other practitioners and health professionals. This is particularly the case if the practitioner acts with undue authority and acts with what Shay and Munroe describe as the sometimes ‘unallocated, God-speaking’ voice of health professionals.66

Conclusion

Unlike St Longinus, the mauling that many veterans suffer as a result of issues such as shame, anger, self-abuse and depression are genuine, lasting and painful aspects of their lives. For a RSCP, or indeed any treating practitioner, to make a meaningful contribution to the treatment of an SW&I they must put aside their own unallocated, God-speaking voice and make a determined understanding of the particular nature of an SW&I. A SW&I starts with a break in an individual’s relationship with their concept of God. The manifestation of the SW&I may then follow a pathway such as the PCB&RA Model.

This paper acknowledges that, in some respects, the behaviours of a SW&I may seem very similar to many mental health or general wellbeing issues. Indeed, in many cases, the treatment of SW&I may well utilise similar treatments and management approaches to MI or mental illnesses. The elements discussed in the PCB&RA Model are; however, all predicated on seeing these conditions, behaviours and actions through a spiritual lens.

Corresponding Author: Murray James Davies, murray.davies62@gmail.com

Authors: M J Davies1

Author Affiliations:

1 University of Divinity Melbourne