Introduction

New Zealand led the world as the first country to implement a standardised level of training leading to registration with the Nurses Act of 1901.1 This signalled the beginning of a proud tradition of nursing, attracting women from all walks of life. Following the Boer War, nurse leaders in New Zealand recognised the need for a trained Army nurse workforce; however, the military and government of the day took longer to accept this need. While the 1908 Defence Act allowed for the formation of the New Zealand Medical Corp (NZMC), with a nursing reserve,2 the formation of a separate nursing corps took a few more years.3 The 1910 visit to New Zealand by Lord Kitchener helped the movement gain momentum, albeit at a snail’s pace.4 In March 1914, the Matron-in-Chief, Hester Maclean, was requested to form a New Zealand Army Nursing Service Reserve to be available for duty with the New Zealand Defence Force and as a reserve to the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS). This proposal was politically fraught, with Hester Maclean constantly battling to secure an independent New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS). When war was declared in August 1914, Hester was informed her nurses would not be needed for overseas service but to enrol nurses ‘anyway’. Six nurses were immediately sent to German Samoa under the banner of the NZMC to provide hospital care there in August 1914. When these nurses departed New Zealand, they had no idea where they were being sent.5

By October 1914, at least 400 New Zealand nurses were willing to sign up for the newly formed NZANS.6 They knew they were needed overseas as casualty lists started filtering through to New Zealand newspapers.7As the New Zealand Government continued to procrastinate about sending nurses overseas, many made their own way, joining up with other agencies such as the French Red Cross or QAIMNS.8 These early nurses were highly valued by the New Zealand soldiers they came into contact with.9 By December 1914, an anonymous letter to the editor (signed Red Cross), begged for at least 50 nurses to go to war. The letter noted the nurses high level of training and their value on board the ships in managing disease and injury. Also, if the British War office did not want them, the New Zealand nurses should be offered to the French War Office.10 Finally, the government and military accepted that New Zealand nurses were needed, and in January 1915, 50 nurses were hand selected by the Matron-in-Chief from a preselected pool of 100 nurses. These nurses were carefully selected to represent the provinces and main centres and meeting criteria, of age and experience. Preference was given to those who had expressed interest in military nursing in peace time.11 As the selected nurses would be fully qualified, the War Office felt they would not need additional training in a military camp before departure. Ten of the 50 were ranked as Sisters, and the rest as nurses, all with the rank of officer and all were signed up for the duration of the War. The Matron-in-Charge would receive £150 per annum (p/a), the Sisters €120 p/a, and the nurses £100 p/a. They received one free outfit, and either meals and accommodation were provided, or a daily allowance of 3 shillings and 6 pennies would be paid.12 Before the first 50 left, nine other nurses had privately and unofficially left to work for the War Office on 2 March 1915. Even though they were not allowed to wear badges the nurses bent the rules slightly and ”had the letters ‘N.Z.’ worked in scarlet silk on their dresses—this was much appreciated by the New Zealand ladies”.13 While these nurses were going unofficially, it seems it was done with the tacit approval of the government as representatives went to the port to wave them off and wish them well.

As they would become known, the official ‘First Fifty’ nurses were attested in two batches, with most on 26 March 1915 and the rest on 6 April 1915. Newspapers widely reported this important decision, with local newspapers celebrating ‘their’ nurses who were selected to serve.14 For example, civic ceremonies were held, and gifts such as travel luggage, cushions or gloves were presented.9 The SS Rotorua sailed from Wellington to an unknown destination on 8 April 1915, which left very little time for personal preparation. The SS Rotorua arrived in London on 26 May 1915,15 a month into the Gallipoli campaign. The nurses had to be Pākeha (European descent), aged under 45 and have 6 years of post- registration experience. While the initial rules did not state they had to be unmarried, it was assumed that, as registered nurses, they would not be married in any case. This became an issue for some as time passed and nurses married overseas. These nurses prepared as well as they could for their journey to Europe and underwent medical testing (including pelvic examinations and inoculations) and brief military preparation. They were the cream of the crop of New Zealand nurses, carefully picked from places around the country so that no single hospital would be depleted. They were fit and healthy, signing up ‘for the duration of the War,’ with no expectation of being able to sail back to New Zealand for a break. The nurses would have been on duty on the ships, caring for the health and welfare of soldiers who succumbed to infections or became injured while on board. No doubt each of them wanted to be doing ‘their bit’, as some reportedly said, ‘What could be better than a soldier waking up in a hospital and hearing a New Zealand accent?’ The battle to have them recognised as officers is another tale beyond the scope of this article, and was ongoing even with the types of awards they received.16

Medical historians have undertaken significant work to understand the effects of war on fighting men, especially around what was commonly referred to as shell shock17 (now known as post-traumatic stress disorder), reconstructive surgery, long-term rehabilitation and the risk of long-term illness and life-limiting conditions directly related to war. A detailed analysis of all the NZEF soldiers found that those who went to the War early had a shorter life span by some eight years, compared to those soldiers who entered in the last year or so.18 The incidence of suicide due to effects of war were also calculated and recorded to be higher than the general population rate.19 While these authors recognised gaps in knowledge about the long-term health effects of World War I (WWI) on military personnel, there is no mention of the health of nurses as serving personnel.20

Some NZ nurses returned broken, ill and suffered ill-considered treatment by the military in providing care and welfare. Apart from the acknowledgment and recognition of the 10 nurses’ lives lost with the sinking of the Marquette on 23 October 1915, taking the lives of 32 New Zealanders in total,21 little attention has been paid to the ongoing health impacts of the War on nurses. Analysis of the marketisation of the image of Anzac nurses provides further opportunities for these nurses to be held in high regard for their sacrifice and reverence, especially around the time of the commemoration of 100 years of WWI.22 By 1916, it was reported that 357 NZ nurses were overseas, of which 14 had returned to NZ sick, two were sick in England, 11 had died and 34 were in an unknown location.23 To address this gap in understanding what WWI nurses experienced, this paper analyses the impacts of the War on the ‘First Fifty’, a unique group of nurses who served the longest time overseas.

Method

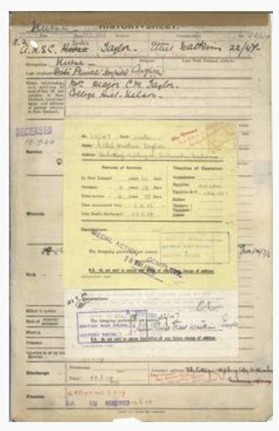

A list of the first fifty nurses was obtained24 and confirmed on the Auckland War Museum Online Cenotaph.25 Twelve nurses had already left New Zealand prior to the ‘First Fifty’ and travelled with the Australian Army nurses; therefore, they were not considered part of the NZANS. As some of the online records had missing data, such as a date of death, further cross-checking was completed by searching for wills via Archives New Zealand1 and obituaries or newspaper mentions via an online search of https:// paperspast.natlib.govt.nz using the names of the nurses. The digital newspapers go up to 1971. An excel spreadsheet was created, and each nurse’s file(s) was downloaded from Archives New Zealand. The originals of these files are held at New Zealand Defence Force Archives at Trentham Military Camp and are not available for viewing due to their fragility. Each file was downloaded and coded. They were checked to confirm they had sailed with the ‘First Fifty’ by date of sailing and ship name and that they had served overseas. Other missing details were searched for in each file (such as confirmation of death, married name, places of service, medals and any other correspondence relating to their service). The spreadsheet was on a shared drive, and each file was checked at least twice to ensure all possible information related to the project was obtained. Most files contained a summary sheet (see image 1 for an example), making it easy to calculate service length. If these were missing, length of service was calculated from other information in the files.

Image 1: Example of the front section of WWI nurse file showing a summary of service, theatre and medals. Most files had this information

Results

Files for each of the nurses were obtained (n=50). In some cases, there were several files relating to each nurse, some with married names and some with names misspelled. Some files contained only a few pages, and others had dozens. Each nurse was issued a service number starting with the prefix 22/XXX. Those in the ‘First Fifty’ had the numbers 1–50; however, some nurses had files with different numbers as the sequencing changed. In addition, some nurses had already commenced service and had a number change.

The average age of nurses at enlistment was 34.18 years (range 28–44 years). This differs from an earlier account stating the average age was 27.26

As nurses were required to have 6 years of post- registration experience, and registration could only occur after the age of 23, the older age range is not surprising. However, even in this first group of 50, exceptions were made regarding the service length as the average length of service on enlistment was 5.46 years (range 3–11 years). None in this group were killed on service,26 or in the Marquette (1915) sinking, and all returned to NZ after serving.

Where a date of death could be confirmed (n=48), the average age at death was 78.8 years (range 52–101 years). The life expectancy of women born in New Zealand in the 1860s/1870s was 54; however, this lower overall life expectancy is due to the high incidence of childhood deaths from disease.28 Once people survived childhood, their likelihood of reaching an older age was increased. A comparative figure is for women born in 1881 and lived to the age of 45, who could reasonably expect to live another 30.8 years (i.e., to 76 years).28 Based on this, the cohort of nurses had a slightly longer average lifespan of approximately two years. However, whether this was in spite of their service (chance) or because of their service (e.g. inoculations, good nutrition) or something else, it is not possible to say due to the small number involved.

Some of the ‘First Fifty’ nurses did not return to New Zealand until 1919 when the final repatriation of soldiers occurred. These nurses had signed up for the duration of the War in 1915, and their average length of service was 3 years and 264 days (range 2–4 years and 223 days). Within that time, nurses would have had some leave and days off; however, this is often not formally reflected in their files. Nurses working in New Zealand at the time worked a 6-day week and had two or three weeks leave a year. Time off on service was likely ad hoc as nurses’ diaries from the time show photographs of nurses at leisure visiting the pyramids or Cairo markets, for example.

Sister Mable Crook, who spent time working on the HS Nevassa (also spelled Nevasa) and HS Somali, noted in her diary, ‘We had arranged a picnic at the gardens with most of the Sisters, M.O’s & ships officers coming. We had a jolly time … we stopped off at Geoppi’s (sic) & had strawberry & cream. Got back to boat at 4pm. Ship had orders to proceed to Port Said…’2

Most of this initial cohort of nurses worked in Egypt, with some then going to France and later working in NZ military hospitals in England (Brockenhurst and Walton-on-Thames). Several were sent to train as nurse masseuses later in the War, as it became recognised that extensive rehabilitation for soldiers would be needed and that it is considered a lighter workload.29 Two of the cohort were sent to train in the treatment of ‘infantile paralysis’ (polio). As both nurses had suffered severe illnesses, perhaps this was seen as a way to offer a lighter workload while retaining their expertise. New Zealand experienced its first documented polio outbreak in 1916.30 Others spent their entire time on hospital ships either transporting wounded from Gallipoli or other places to Egypt, or when the permanently injured were sent back to New Zealand.

Ten nurses returned to New Zealand with less than three years of overseas service, and these were clearly the exception. Five (10%) were invalided back to New Zealand with chronic illnesses, stopping them from ever undertaking military nursing again. These illnesses included chronic anaemia, fatigue, enteric fever (typhoid), nervous debility and at least two with chronic bronchitis, which was likely to be tuberculosis (TB). The nurses were discharged on their return to New Zealand, and no further information was available in their military files. Two nurses continued to receive treatment for months in New Zealand while still technically ‘in service’. Hence, their medical records are visible in the military files. Despite their illness, some nurses were required to work ‘light duties’ while being transported back to New Zealand as invalids, suggesting the military was prepared to get every bit of effort from them. The term ‘light duties’ is not well defined and could mean anything from a shorter duty day to not being involved in cases that involved lifting to sitting with patients reading or writing letters for them.

Image 2: Nurse Mabel Crook aboard the Nevassa. Photo supplied by National Army Museum Waiouru and right to use purchased

As mentioned previously, getting married was not expressly forbidden; however, three of the 10 nurses who came home early requested their discharge a short time after marriage while on service. Another had an undisclosed illness, which kept her in hospital for a few days, immediately prior to her request to be discharged (a reasonable assumption is pregnancy) after almost 3.5 years of service and getting married shortly after Armistice Day3. One nurse was able to get married on a fleeting trip back to New Zealand with a hospital ship. She returned to Egypt and, a few months later, requested discharge back to New Zealand. It is unknown why the other two nurses came home earlier than their peers, as their records gave no indication.

Twenty-seven of the 50 nurses had details of sick leave or medical boards in their files, and these contained stark details of the impact of their sicknesses. This group’s average number of sick leave 75 days (range 8–365 days). These calculations include the time counted as sick when they returned to NZ before being discharged from service. Those who arrived back invalided likely remained unwell after their service was complete. For example, when Sister Mabel Crook was met off the boat by Hester McLean, Matron-in-Chief, she took one look at her and told Sister Crook she was being sent straight to hospital. The nurses were affected by a range of illnesses directly attributed to working long hours in cramped conditions with poor hygiene. Indeed, most documented illnesses are now preventable by either vaccination or antibiotics. These are detailed in Table 1. The number adds up to more than 27, as some nurses were diagnosed with several illnesses over their time.

Table 1: Illnesses suffered by nurses

| Medical condition as stated on medical files (italics author comments) | Number of times recorded in files |

|---|---|

| Bronchitis (likely TB) | 4 |

| Enteric fever (probably typhoid but not stated) | 2 |

| Gastritis/enteritis/dysentery | 6 |

| Neuritis or other ‘nervous’ disorder (some files stated ‘nervy’—palpitations or later ‘hysteria’) | 4 |

| Fatigue/debility (exhaustion or due to anaemia) | 3 |

| Measles | 2 |

| Influenza | 4 |

| Sciatica (possibly following an injury) | 1 |

| Unexplained weight loss (likely due to TB) | 1 |

| Not stated (possibly pregnancy for 1 as recently married and requested immediate discharge) | 3 |

| Injury (mostly due to falling/tripping over on duty) | 3 |

| Typhoid | 2 |

| TB diagnosed | 2 |

| Erythema nodosum (inflammatory skin condition) | 1 |

Image 3: NZ patients at Codford Hospital UK, with an unnamed Red Cross VAD and Nurse Mabel Crook (back row in uniform). Photo from National Army Museum Archives used with permission (undated estimated to be 1917)

Discussion

It was clear that the military recognised that the nurses would need some time away from their duties either as recreation or as some form of convalescence. For example, nurses in Cairo had access to a rest home, or a houseboat on the Nile provided a home for nurses to rest.31 In addition to Cairo, homes had been established in Sandwich and Brighton, England, for the rest of New Zealand nurses to use. When nurses got sick, they were often out of operation for weeks at a time, usually cared for in the hospitals where they had worked or sent to one of the convalescence homes.

There was long-term planning around the rehabilitation of soldiers once they returned to New Zealand, as several nurses completed additional training in massage therapy specifically to treat the wounded. Speciality rehabilitation hospitals were set up in Rotorua (North Island) and Hanmer Springs (South Island). These places had the benefits of thermal springs, clean mountain or lake air and a quiet location to aid the long-term recovery of the soldiers.32 This care was provided free to soldiers. However, there was no consideration that nurses might also need these facilities once they returned, as several of the ‘First Fifty’ found out. Nurses who were sent to Rotorua or Hanmer Springs as patients were given a train pass and sent on their way. However, they were expected to pay for private boarding and attend the hospitals as day patients as there was no accommodation for them at the hospitals. The subsistence allowance did not cover the cost of full board and lodgings, and the nurses may have required months of treatment. In other cases, nurses were again sent to work for ‘light duties’ at one of the military hospitals to get their lodgings, but still an expectation of some work effort was required.4

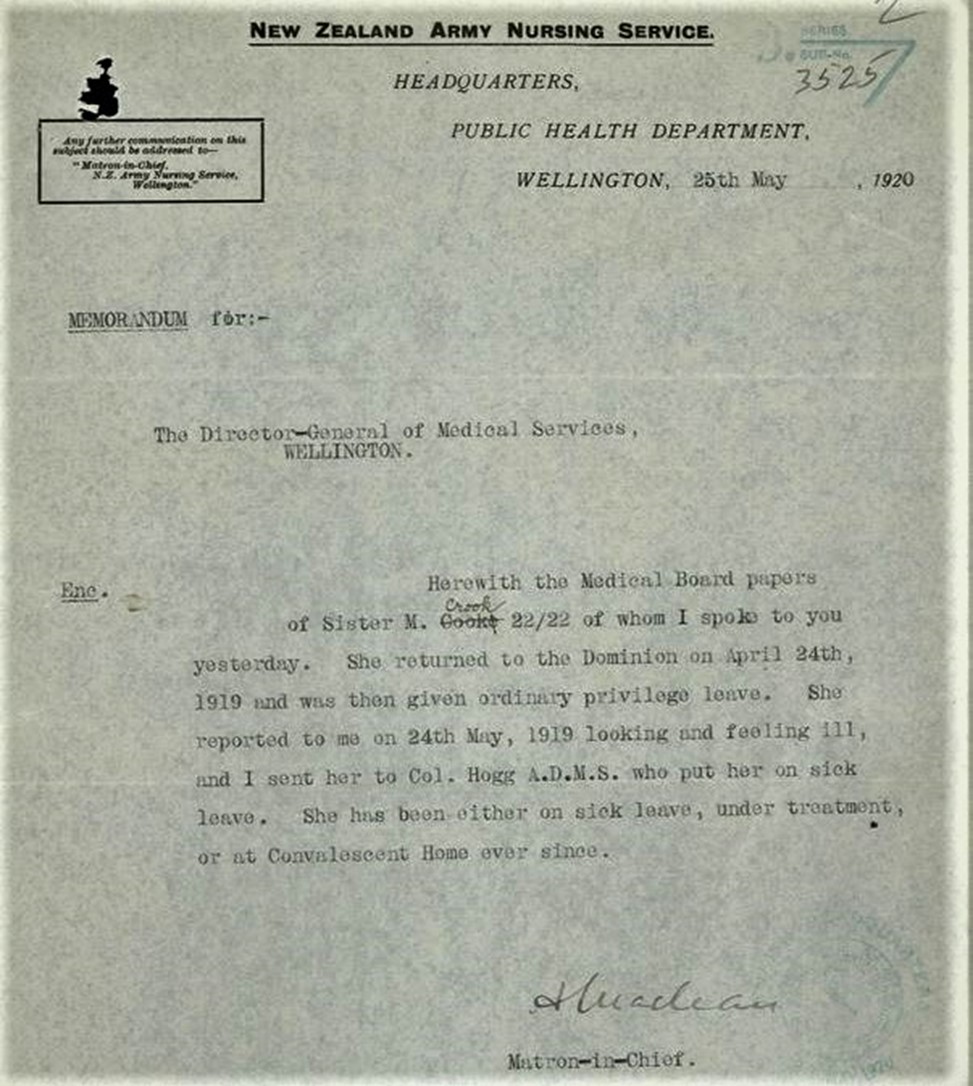

Image 4: Letter in file of Nurse Mabel Crook, indicative of the length of her service and the impact on her wellbeing. Relating the intensity expressed in this letter with the smiling young confident woman of the earlier photos is heart-breaking (image adjusted to allow text to be prominent—screen shot taken by author from the online file)

None of the nurses were given a diagnosis that more explicitly suggested a mental disorder, such as depression or anxiety. However, this could be implied by using the term ‘neuritis’, which was present in several files, as either suggestive of a physical disorder affecting the nerves (such as through an injury) or a nervous disorder. At least one nurse was medically diagnosed with ‘hysteria’ to describe an acute state of mental distress. Nurse Mable Crook’s file contains correspondence showing how unwell she was when she arrived at Hanmer Springs (for ‘light duties’ to stay in the nurse’s home). It is hard to reconcile those reports with the earlier smiling photos. The doctor in charge recognised how unsuitable this situation was and immediately admitted her as a patient and commenced a lengthy correspondence with defence headquarters.

Another file notes the nurse was ‘nervy’, with very abnormal vital signs (fast heart rate). She was eventually diagnosed with a disorder of her adrenal glands, after many investigations. The nurses worked relentlessly in trying conditions, seeing hideous sites daily, especially as the War went on and nurses moved closer to the front lines in Western Europe. They knew their work was dangerous, as hospitals were often shelled (with nurses also being killed) and hospital ships torpedoed.

Conclusion

This exploratory study of the ‘First Fifty’ New Zealand nurses who served in WWI has identified that more than half of the nurses had documented serious illnesses, resulting in long periods where they could not work. As the remaining files were incomplete, this number was likely higher. Ten per cent of the nurses returned to New Zealand as invalids before their service was over, with less than three years of overseas service. These nurses could no longer serve as military nurses; however, they may have been able to return to a civilian nursing role. These 50 nurses started their war service in peak physical condition and had been well-trained in their clinical skills. Most of these nurses were awarded some form of gallantry award, either mentioned in despatches (MID) or a Royal Red Cross medal. This supports the calibre and experiences of the nurses through their service. Most of the 50 appeared to go on and live full lives, with an expected life span for the time. The two who died under the age of 60 had a note in their defence files that the death was not due to their medical service.

At least three specially commissioned convalescence homes in Cairo and England provided opportunities to rest while on active service. Photo collections show nurses relaxing or sightseeing at exotic locations such as Cairo or Alexandria or picnicking in the English countryside.5 However, these images do not show the effects of illnesses such as measles, dysentery, tuberculosis or typhoid fever. In addition, terms like fatigue and neuritis are loaded with other possible interpretations. Undoubtedly, these nurses gave the best of themselves while on service, and the official records do not show the total personal cost of what was involved or the ongoing battles they had with the military. In addition to the big picture issues, nurses were constantly battling the minutiae of conforming to military life. For example, one of the nurses fought for weeks to have her expenses reimbursed after she took her luggage on a train after returning from 5 years overseas. Her file contains 15 correspondences relating to this matter, which eventually was resolved.

There is enormous social and historical value in further investigating the full nursing contingent from WWI and sharing these results to help complete the understanding of nursing in WWI and what happened to these nurses. A more extensive study of all 660 New Zealand nurses is under way.

Corresponding Author: W. Maddocks, wendy.maddocks@canterbury.ac.nz

Authors: W. Maddocks1

Author Affiliations:

1 University of Canterbury – School of Health Sciences